Gender and the Explicit Hands of Middlemarch

by Aaron Ellsworth

Introduction

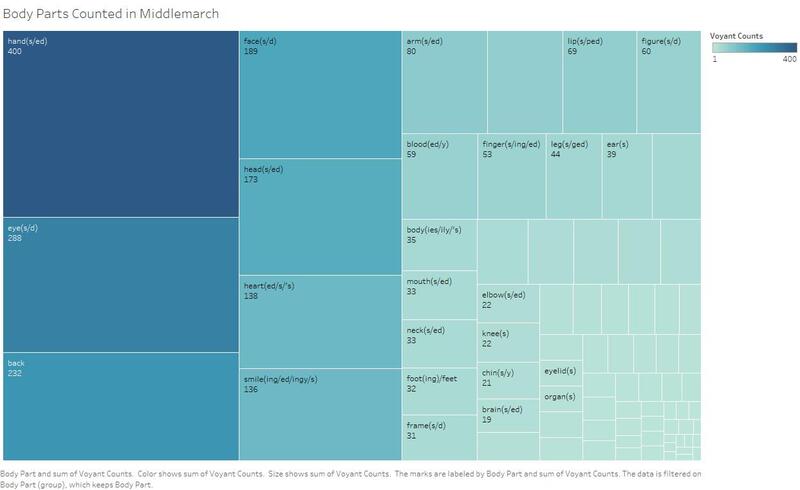

Hands are a significant body part in George Eliot’s Middlemarch. As Peter J. Capuano correctly points out, Dorothea’s “finely formed” hand and wrist are the first body parts mentioned describing her, even before her face (Capuano 9; Eliot Chapter I 33). [Note: All Middlemarch citations include pagination from the Broadview edition edited by Gregory Maertz]. Earlier, in the prelude, Eliot presents St. Theresa as a child walking “hand-in-hand” with her brother, only later describing their “wide-eyed” looks (Eliot 31). As my first graph below shows, the words “hand” or “hands” appear four-hundred times in the novel, easily outpacing any other body part invoked by name. Truly, there is something to be said about George Eliot’s use of hands.

My project counts 282 instances of the words "hand" or "hands" within Middlemarch's story world, situating them in the contexts of characters, verbs, objects, and persons touched or gestured toward. Verbs, by themselves, do not seem to clearly indicate gender difference; with the male-gendered “thrust” being a possible exception. On the other hand, (pun intended), the data shows patterns of gender expression within the novel; male characters touch their bodies with their hands in different places than female characters, and characters hold objects which are then imbued with gendered difference, as they are seemingly focused on different spheres. The rules I followed in gathering my data points will be discussed after the first graph below.

This spotlight on hands is not unique to my project, or to Eliot; scholars such as Capuano, Aviva Briefel, and Jonathan Cheng have each examined the hand as it appears in the larger spheres of Victorian literature and culture. In his book Changing Hands: Industry, Evolution, and the Reconfiguration of the Victorian Body, Capuano argues that Victorians became highly aware of their hands because of developments in mechanization and in evolutionary theory which marked “a radical disruption of this supposed distinguishing mark of their humanity” (2; see 13). Unlike my project, Capuano’s work is largely close reading of Victorian texts, with a historicist approach, utilizing “thing theory”, where the thing studied is hands (11). That said, Capuano does dip into a “macro-data” approach, noting a “spike” where “hands appear in nineteenth-century novels around eight times more frequently than in all genres of eighteenth-century texts (12; see his note 2 on 257). Hands appear so frequently in Victorian novels that they outpace all other body parts – including “faces, heads and eyes” (12) – much as my first graph below shows regarding Middlemarch itself. While mine is an approach focused more on the metadata (with some dips into close reading as appropriate), like Capuano I take fictional “hands that remain very much alive while connected to the bodies they serve” as my subject (14).

Much like Capuano, Aviva Briefel, in her The Racial Hand in the Victorian Imagination, undertakes a series of close readings focused on hands – looking at “detached hands” as a lens into race, ethnicity and colonial relationships (2). Briefel’s introduction provides marvelous insight into Victorian views on the hand. She writes about the proliferation of “various modes of palmistry… or chirognomy” (3), and the emerging science of fingerprinting (4). Thus, the hand was considered a source of truth about identity (through fingerprinting) and even about a person’s character (via chirognomy) (7); “Unlike the face, however, the hand supposedly could not lie” (3). Though Briefel does not consider Eliot, or Middlemarch, it is intriguing to consider the novel’s hands as “honest,” revealing gendered aspects of character. However, Briefel makes it clear that hands were seen as revealing truth about individuals, not as clear markers of categories, such as racial or ethnic difference (16-17). Therefore, while I am looking at gender, perhaps a level of skepticism regarding patterns should be observed, while allowing for individual performances of gender within the novel.

Unlike either Capuano or Briefel, Jonathan Cheng undertakes a large distant reading of Victorian hands in his “Computation and the Gendering of Gestures.” Using a corpus of 905 nineteenth-century novels (ranging from 1782 to 1903 [151]), focusing on the gestures (that is the verbs) associated with gendered instances (pronouns or nouns indicating gender [151, 153]) of the words “hand” and “hands”, Cheng shows that while “at the end of the eighteenth century, female and male characters tend to perform a distinct range of hand gestures” (150), the gendering of gestures becomes more difficult towards the end of the nineteenth century as the verbs used “increasingly overlap” between female and male characters (150). When presented with a verb Cheng’s model was able to predict “the gesturing character’s gender eighty percent of the time” (that is thirty percent better than random chance) (162), however the later the book appears, the “less confident” the computer program was in making a gendered prediction (162-63). Therefore, Middlemarch appearing in the early 1870s should have a less distinctive gender divide when looking at the verbs. Still, Cheng’s project identified ten verbs that corresponded to men’s hands and ten for women’s hands (165); he invites others to utilize these lists in the study of particular texts (170), which I shall below.

Body Parts Counted in Middlemarch Using Voyant

Using a program called Voyant, I was able to count instances of words indicating body parts. As can be seen in the above visualization, the most frequently mentioned body part is hands, with 400 instances of the words “hand,” “hands,” or “handed.” The second through seventh most frequently mentioned body parts thereafter tend towards the face, or head. (Please note that “back” includes any use of the word, even if it does not refer to the body, thus it may be falsely inflated to its third place). Therefore, like other Victorian works, Middlemarch has a clear focus on hands.

My method of data collection is decidedly low-tech compared to Cheng’s project; using the Project Gutenberg e-book version of Middlemarch, I searched for “hand” finding 552 instances of words starting with hand. This method captured words such as “handsome” which I obviously skipped. I then manually examined each instance of “hand” or “hands,” recording in a spreadsheet the name of the character the body part belongs to, their gender, any verbs associated with the hand, whether the person touched or gestured toward an object, animal, or person (identifying those if yes) with additional relationship info if there was person to person contact. The spreadsheet was then read by a graphing program called Tableau, so that I could create the various visualisations seen here (thanks to Dr. John Brosz, Data and Visualization Curator at the University of Calgary’s library for helping me set up and re-learn Tableau).

My sample size was reduced to 282 hand instances through the application of certain rules. First and foremost were two rules: first, it must be a real hand within Middlemarch’s story world (thanks to Dr. Karen Bourrier for this suggestion) and second, it must be an explicit hand; it must say the word “hand” or “hands” in the text, rather than implying it. Rule one excludes hands in the epigraphs, Book Five’s title, and the scene in the prelude with St. Theresa and her brother. Sayings such as “on the other hand” or “at hand” along with the verb “to hand” are discarded. Some figurative hands were also excluded, such as “I wash my hands of the marriage” spoken by Mrs. Cadwallader (chapter VIII 83), the hospital’s management being “in the hands” of the directors (XLV 368) or the phrase “earned your hand” referring to marriage (LII 417). The lines are not always clear cut, for example, sometimes Eliot describes handwriting using the word “hand” (LVI 450), other times the hand that writes could be described (V 64). Therefore, the elimination of figurative or metaphorical hands was done on a case-by-case basis, any errors being my own.

The second rule, that the hands had to be explicitly in the text, created some counter-intuitive moments. Sometimes a character would do something with one hand, and something else with the other; but only the first hand is explicit, the second is only implied by the word “other” and is thus not counted (see XXXI 257). Then there are the times when people touch hands: If A’s hands touch B’s hands and both have the word “hands,” then both are counted; if B’s hands are implied, then the encounter is recorded only from A’s perspective (A is the Character Named, B becomes the Person touched with the body part touched being “hands”); unfortunately, if B’s hands are explicit and A’s are implied, the encounter is recorded from B’s perspective (B is the Character Named, A becomes the Person touched, etc.). This may give the false impression that B is the subject of the sentence and thus the toucher. The same problem affected the verbs. When it comes to the verbs associated with hands, I eventually decided to follow Cheng’s lead. He correctly noticed that the words “hand” or “hands” can be either the subject or the object of the sentence’s verb (164); he found them to be objects of sentences eighty-eight percent of the time (164-65). The problem this presents is that, as Cheng notes, “characters’ hands often move as the object of other characters’ actions” (164 italics in original). While I counted thirty-nine times this occurs in Middlemarch (out of 282 hands), I had no way of looking at verbs as a whole if I separated them. So, while most verbs are of a character doing something with their own hands, on occasion it is another character performing the action. Likewise, rarely the named hand is the one touched.

“Shaking hands” proved difficult as well. Sometimes it was unclear if a handshake had occurred, even if one was offered, such as in the phrase she “held out her hand to him” (XXI 188). Unless the handshake was real given the rest of the sentence, these were handled as “gestures” toward another character, with no body part touched. When shakes did occur, it was mostly clear whose hands were involved, and I tended towards the subject of the sentence being the “Character Name”. Twice, Eliot simply states, “they shook hands” or some variation (XXVII 236 with Rosamond and Lydgate and LXVI 526 with Farebrother and Lydgate); in those cases, I defaulted to the subject and object of the rest of the sentence (and the previous one) to identify the “Character Name” and the “other person.” This was done, perhaps erroneously, to keep the shake to one entry as hands were only mentioned once. Additionally, twice it seems like Arthur Brooke shakes hands with more than one person (XXXVIII, LXXXIV 318, 623), but he only addresses one by name, so I put that person in as the “person” touched.

Lastly, in the stormy climactic scene where Dorothea and Ladislaw finally agree to be wed, the couple hold hands with the word “hands” appearing in two sentences (LXXXIII 621). While in the first sentence Will seizes Dorothea’s hand (which I counted as a separate hand mention), in the latter two explicit mentions it is impossible to separate Will and Dorothea’s hands categorically. Both characters are named as subjects and after a semi-colon “their hands clasped”. In the second sentence, Eliot uses only “their” and “they” to describe the continuing hand hold. Essentially, this action is completely reciprocal much like the kiss which follows (LXXXIII 621). My inelegant solution for rendering this event into data was to record each of the two “hand” mentions twice, once for Dorothea, and once for Will.

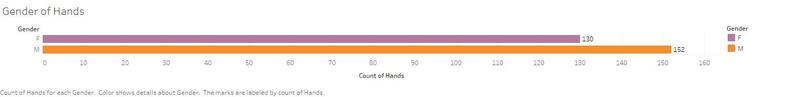

Gender of Hands

To discuss the gendering of hands in Middlemarch a base line is required. The above graph shows an almost equal distribution of explicit hands between the binary of female and male characters; with male hands only appearing twenty-two times more. Cheng shows that closer to the 1880s, “in novels by both men and women, the representation of men’s versus women’s hands becomes stunningly close to proportionally even” (150). This is partly because, for some reason, as his data shows, female authors both “wrote less about women’s hands” and began writing more about men’s hands (159). Though Middlemarch would only be one data-point, it appears that Eliot was following the trend that Cheng notices.

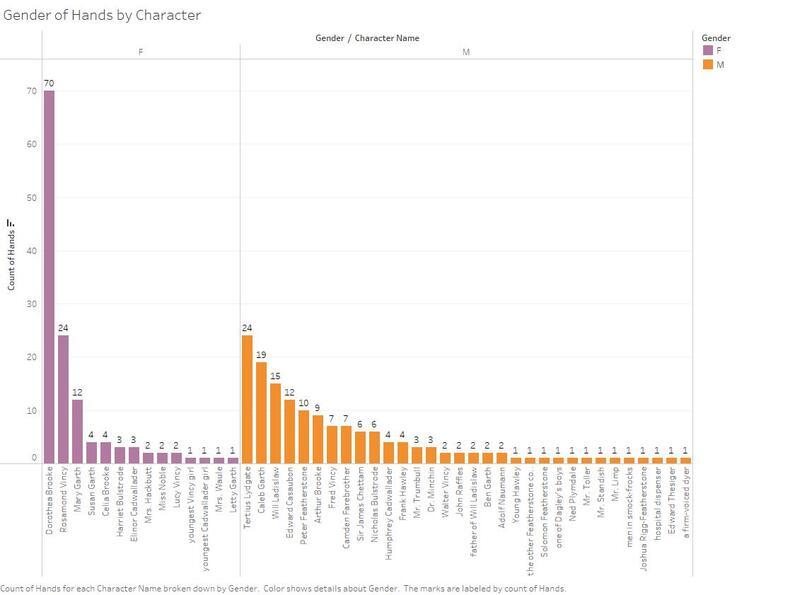

Gender of Hands by Character

The above graph shows the number of explicit hands by character, coloured and divided to show the gender. Eliot mentions Dorothea’s hands the most by far, with Rosamond and Lydgate tying for second place. The female side seems focused on the three romantic leading ladies – Dorothea, Rosamond, and Mary – with other women’s hands mentioned far less frequently. The male hands, on the contrary, are more widely distributed among major and minor characters, with some surprising men’s hands appearing quite frequently. Peter Featherstone’s count of ten, owes a lot to his deathbed scene, where he handles money and keys trying to get Mary to do his bidding (XXXIII). Caleb Garth, Mary’s father, is second amongst the men, partially because he talks and thinks with his hands in motion (XL 339 and LVI 439-40, 449 for example). In total, the hand distribution seems to affirm Dorothea as the main character but shows that Eliot created quite a few male characters which she embodied with hands more frequently than most of the female cast.

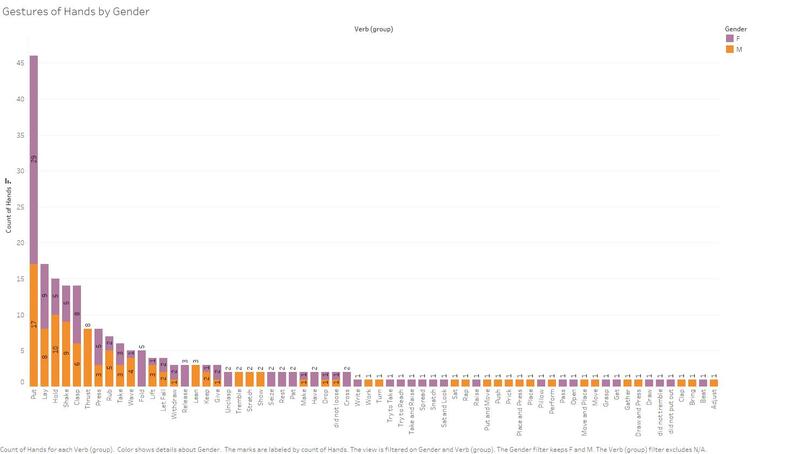

Gestures of Hands by Gender

Following the same gender colouring as the previous visualisations, the above graph shows the verbs, what Cheng calls gestures, associated with hands throughout Middlemarch. Remembering Cheng’s finding that towards the end of the nineteenth century the verbs used “increasingly overlap” between female and male characters (150), it is perhaps unsurprising that most of the hand-verbs are shared fairly evenly across genders; at least for the more frequently used verbs. Please note that each verb has been grouped by the verb root: “put” for example includes the varieties “put out”, “put out to”, “putting out”, “put on”, “put into”, “putting into”, “put before” and “putting against” among others. Cheng argues that while the verbs themselves “may decreasingly function as a sign of gender” perhaps other aspects of the gesture, say tense or adverb or other “subtler forms” may gender it (168). I examined the variations of the top five verbs – put, lay, hold, shake, and clasp – individually, but could not discern any major differences in gender expression based on adverbs or tense. If a variety was all male or all female it usually occurred only once or twice, or to or by the same character’s hands. Therefore, either the sample size is too small to say anything about the tense or adverbs being gendered, or maybe certain varieties of these verbs are idiosyncratic to a character, not to a gender. Perhaps the five frequent verbs, in all their varieties, are truly less gendered in Middlemarch. That said, certain verbs, such as “thrust”, and “fold” seem to be more clearly gendered. “Thrust” I will discuss below; “fold” however connects with characters touching themselves; three times Rosamond folds her hands “before her” (XLV, LXV, LXXVIII 371, 520, 598) and twice Dorothea folds her hands on her lap (LIV, LXXXIII 431, 621). Folding one’s hands is a feminine gesture in Middlemarch, simply because only women do it.

Gestures of Hands by Gender - Cheng's 10 Feminine

The above graph shows Middlemarch instances of hand-verbs that Cheng “identifies as most indicative of feminine hand motions”: take, clasp, wring, give, retain, withdraw, bestow, claim, seek, and press (165). Only five appear in Middlemarch if one combines the variations: clasp, give, press, take and withdraw. The gender distribution of these verbs appears quite even (especially if one adds “Draw and Press” and “Place and Press” to the “Press” column; and “Take and Raise” and “Try to Take” to the “Take” column), perhaps showing evidence of the overlapping noticed by Cheng. While the tense and adverb of “Clasp” alone indicated no gender differences, close reading the instances does reveal some gendered patterns. On the male side, four times a man clasps his hands behind his head, apparently in a relaxed, bemused, or thoughtful state (XVI, XXXVIII, XLV, LXIV 155, 319, 371, 514); and once, the deceased Featherstone clasps his keys (XXXIII 272). The last male handclasp is Will and Dorothea’s mutual one in the climactic scene, which also accounts for one of the female handclasps (LXXXIII 621). Conversely, women clasping their hands hit a different emotional register. Three times women simply clasp their hands in excitement or distress (XXXIX, LXIV, LXXII 323, 510, 569), twice, much like with the verb “fold,” they clasp their hands “before her” or on the lap (XXXVII, LXXXIII 306, 619). So, like with the males, female clasping can involve self-touch, just not in the same bodily positioning. Lastly, twice it is a male character (Sir James and Will) clasping a woman’s hands (Celia and Rosamond respectively) (XXIX, LXXVII 247, 596); the latter being the scene when Dorothea is shocked to see Will and Rosamond together. Following Helena Michie, Cheng argues that the “give” and “take” aspect of women’s hands speaks towards the access to the whole “sexualized female body” (166); perhaps this is partially true for “clasp” as well. It would explain Dorothea’s horror upon seeing Rosamond and Will in what amounts to a potentially intimate embrace, one that Dorothea and Will share only once they reconcile. Thus, perhaps in Middlemarch certain verbs’ contexts can be used to see a difference in the expressions of gender specifically, self-touches and romantic touches along with their associated emotional resonances.

Gestures of Hands by Gender - Cheng's 10 Masculine

Similar to the previous graph, this one shows Middlemarch instances of "The ten verbs that [Cheng's project] identifies as most indicative of masculine hand motions”, that is rub, pass, strike, thrust, wave, offer, dash, grasp, stay, and try" (165). Surprisingly, the six verbs – grasp, pass, rub, thrust, try (in two variants) and wave – do seem more gendered, though the ones with few instances are gendered female instead of male. “Thrust,” with eight hand instances is decidedly masculine. Cheng reads the gestures “strike,” “thrust” and “grasp” as “embody[ing] the threat of masculine violence” (166). In Middlemarch men thrust their hands into their clothing, once into a coat (XLII 347), the rest into pockets (XLV, LI, LVIII, LXIV, LXXI, LXXV 364, 408, 471, 510, 557, 566, 585). There does sometimes appear to be an air of frustration or anger involved with the thrust; in Lydgate’s heated discussions with Rosamond, for example (LVIII, LXIV, LXXV 471, 510, 585). However, the fact that the thrust is directed inwardly, seems to indicate a level of impotence in the situation, or a resolve against directing the violence outward. So, some verbs, in tandem with objects (in this case clothes), are indicative of masculine hands.

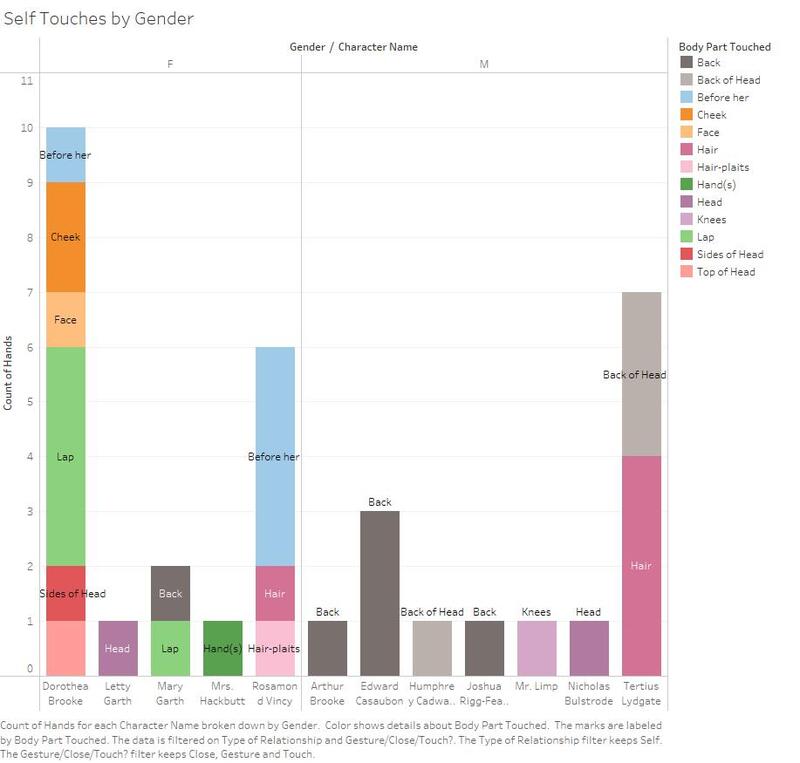

Self Touches

In Middlemarch, men and women position their hands on the self differently. The above graph shows self-touches by character, with women on the left and men on the right. The colours and labels indicate the body part the explicit hand, or hands, touch. These exclude the touching of one’s own hands, as that seemed redundant, the only exception being Mrs. Hackbutt, who explicitly rubs one hand with the other in front of her chest (LXXIV 578). As we saw with the verbs “fold” and “clasp” women in Middlemarch tend to place their hands in front of them; either vaguely “before her” or specifically in the lap. (Dorothea also seems to touch her head or face quite a bit). Alternatively, Eliot’s men place their hands behind themselves, either simply “behind him” (seemingly indicating the lower back, hence the label “back”) or behind their heads. My theory is that Eliot is merely reporting hand positions that were common, or proper, for men and women in the Victorian era. Intriguingly, Mary Garth also puts her hands behind her; does this make her somewhat masculine? Not really; unlike the men who tend to walk or stand with their hands behind them, Mary is actively hiding her hands “behind her” from Fred Vincy’s attempt to take her hand (LVII 459). It would be interesting to see if the trends of hand placements on the self continued in other works by Eliot, or indeed other Victorian fiction.

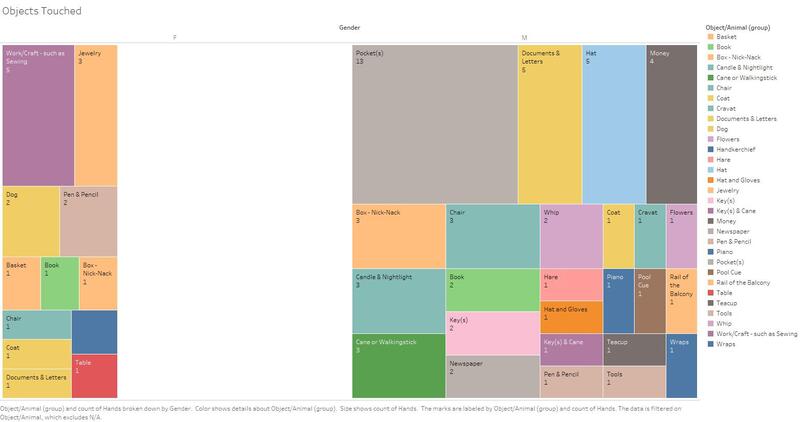

Objects Touched

However, the men of Middlemarch do not just hold their hands behind them; as we saw from the verb “thrust”, they also put their hands into their pockets. The above graph shows all the objects touched (or those “grasped for” or “released” in a few instances), separated by gender (females on the left, men on the right) and coloured by the type of object (or animal). The sizes of the boxes (as well as the labels) indicate how many instances occurred in the novel. (By the way, the blank dark blue square on the female side represents one touch of a handkerchief). Looking back at my second graph, showing the gender of hands, (with 130 female instances compared to 152 male instances), we find that a hand is male approximately 53.9% of the time and female about 46.1% of the time. The ratio is fairly even. Yet out of the eighty instances of objects touched (or reached for/released) 75% are touched by males, and 25% by females. In Middlemarch, male hands are touching things more often than female hands, and not just by virtue of their slightly greater numbers. Additionally, the above graph shows that male characters touch a greater variety of things too. While it is tempting to read this as evidence for male freedom and female restriction, more would have to be done with close readings to make such an argument. Still, the objects touched by gendered hands may offer a lens into the spheres of interest Eliot presents males and females as having in Middlemarch. Looking at the top four things touched for each gender is revealing of expected gender roles; men put their hands in their pockets, touch documents (including wills) or letters, their hats, or deal with money most of the time; women are occupied with sewing and other handcrafts, touch or wear jewelry, pet dogs, and, because of Dorothea, hold pens and pencils. In general, men seem to be business oriented, and women limited to handicrafts and jewelry. Those aspects becoming gendered simply because the hands that are touching them are. While pockets are undoubtably male, there are some overlaps with other objects. Dorothea’s hand explicitly touches a letter, though it is placed there by Lydgate, for example (LXXXI 608). [Odd because readers will be aware that Dorothea writes and handles several letters in the plot, perhaps showing the limits of focusing on explicit hands]. Men and women handle books, chairs, and small boxes. The latter being a tin box holding money, a snuff box, and the auctioned heart-shaped box for the men, and cameo-cases for the women; thus still showing some gendered difference. Male hands are associated with commerce, women’s hands with jewels.

Conclusion

Hands were a focal point for Victorian writers, and this is true for Eliot and Middlemarch. As the most frequently mentioned body part in the novel, hands perhaps offer a lens into characterisations, including gendered expressions. Distant reading of verbs alone, with a few exceptions such as “fold” or “thrust”, does not reveal gendered differences, perhaps giving the false impression of homogeny. Looking at self-touches and objects associated with hands (along with close reading verb instances) helps illuminate the differences of gender performance that Eliot encoded into her novel. Following Briefel, one may ask how or what kind of “truths” these hands reveal about the perception of gendered difference in Victorian times. Additionally, having compiled and viewed the data, I can confidently say more could be learned about the individual characters and their relationships, particularly their romantic ones, simply by looking at their hands.

Works Cited

Briefel, Aviva. The Racial Hand in the Victorian Imagination. Cambridge UP, 2015. Cambridge Core, https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/10.1017/CBO9781316337509.

Capuano, Peter J. Changing Hands: Industry, Evolution, and the Reconfiguration of the Victorian Body. U of Michigan P, 2015.

Cheng, Jonathan. “Chapter 8: Computation and the Gendering of Gestures.” Victorian Hands: The Manual Turn in Nineteenth-Century Body Studies, edited by Peter J. Capuano and Sue Zemka, Ohio State UP, 2020, pp. 148-71.

Eliot, George. Middlemarch: A Study of Provincial Life. Edited by Gregory Maertz, Broadview, 2018.

———. Middlemarch. Project Gutenberg, 2023. www.gutenberg.org/files/145/145-h/145-h.htm.