Quack Medicine of the Highest Quality: An Examination of the Pharmaceutical Ads in Middlemarch by Anika Escher

Medicine and Middlemarch

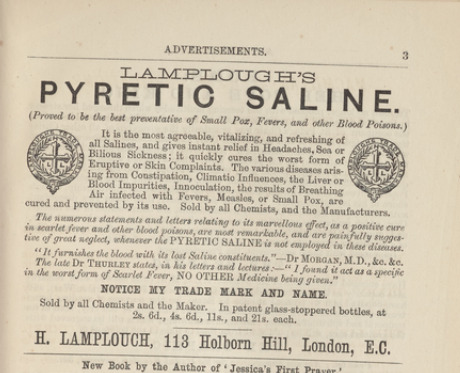

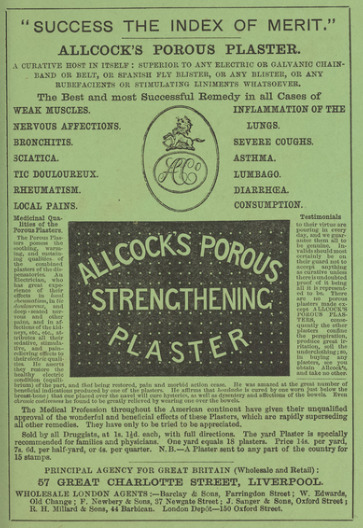

In looking at medical and pharmaceutical ads from Middlemarch’s original eight-part publishing, the 1870s audience was more knowledgeable about, and had better access to, treatments for sicknesses and diseases. Advertisements like “Allcock’s Strengthening Porous Plaster,” which promise that it is a “curative host in itself” (Book 4, inside back cover), and “Lamplough’s Pyretic Saline,” which markets that it is “Proved to be the best preventative of Small Pox, Fevers, and other Blood Poisons” (Book 4, 3), surely led people in the 1870s to believe that they were better off—and much healthier—than their 1830s counterparts. The advertisements are marketed with such assuredness and claim to cure or prevent so many sicknesses, that one could easily find comfort and even pride in their superior scientific and medical advancement. Without doubt, this bias would have influenced readers of Middlemarch as they flipped through the pages of George Eliot’s “study of provincial life” and processed the medical language and events in the narrative. This must have affected how the contemporary audience considered information about medical reform, Lydgate’s ideas and his conflict with the Middlemarch doctors, and especially how they may view the Middlemarchers as medically naïve. In this digital exhibit, using the advertisements and close readings from passages in Middlemarch, I aim to highlight how the several pharmaceutical advertisements signal a greater understanding of science and medicine in Middlemarch’s contemporary audience, and how they would have responded to Lydgate and the Middlemarchers.

Medical Reform

Lilian R. Furst’s article, “Struggling for Medical Reform in Middlemarch,” gives much insight regarding medical reform in both Middlemarch and the context of its 1830s’ setting, but because it opts to focus on the 1830s, the article does not explore the ramifications for medical reform on the 1870s readers of Middlemarch and how they might have considered the issue as it was being discussed in the book, which I wish to highlight. Moreover, if we consider the additional context the advertisements in the original publishing provide us, we can assume the 1870s readers’ thoughts on medical reform. The question of medical reform in Middlemarch is one of tension between Lydgate and the other Middlemarch doctors. Although arguments about the position and organization of physicians, surgeons, and apothecaries were present since the sixteenth century in England, medical reform was an ongoing concern even during the time period of Middlemarch’s setting. Principally, medical reform sought to move towards more scientific methods while practicing, and the reorganization of the medical profession. For one, the profession of general practitioners would be given more permissions and status (Furst 342). As stated in Furst’s article, Lydgate’s position was particularly precipitous because he was a surgeon, like Middlemarch doctors Mr. Wrench and Mr. Toller, but “the categories diving the three ranks of medical men [physicians, surgeons, and apothecaries] were becoming more porous by 1830” (344) and Lydgate refused to dispense drugs to patients when other physicians and surgeons in Middlemarch did. Dispensing drugs was also important because it made physicians and surgeons money, even though money would later become an issue for Lydgate when he marries Rosamond. Lydgate, therefore, seemingly adheres to the rigid organization of medical practitioners that medical reform wishes to change, but this does not mean that Lydgate is against medical reform. Rather, Lydgate’s refusal to dispense drugs is a large issue because it “represents an initiative for reform,” since it does challenge the roles and limits of doctors (Furst 353-4). Moreover, Lydgate is a strong proponent of using modern, scientific methods as seen in his treatment of Raffles, in which he strongly denies traditional treatments using brandy and overusing opium, and by using new instruments like the stethoscope “(which had not become a matter of course in practice at that time)” (Eliot 248). Overall, Lydgate himself wanted to “make a certain amount of difference towards that spreading change” of reform and sought practice in Middlemarch to make a greater difference than he could in cities like London, Paris, or Edinburgh (140-1). Furst mentions that a Health Act was enacted in England in 1848, over a decade after Middlemarch’s setting, which put forward “efficient national sanitary administration” to increase hygiene and reduce the spread of diseases like cholera (354). Although cholera was not discovered to be a water-borne disease until 1849 (354), cholera is a pressing issue in Middlemarch that Lydgate and the Middlemarchers are concerned about, and there are hopes that the New Hospital can help cure and prevent the disease. For the 1870s readers, they could be hopeful that Lydgate will lead them to this discovery, since he fervently pushes for a quarantine when Fred is sick with typhoid fever (Eliot 233), and in a discussion over cholera (Eliot 361), and he has already presented himself as an intelligent, pro-reform doctor, dedicated to creating an improved hospital—to the 1870s audience, Lydgate is the most modern part of Middlemarch.

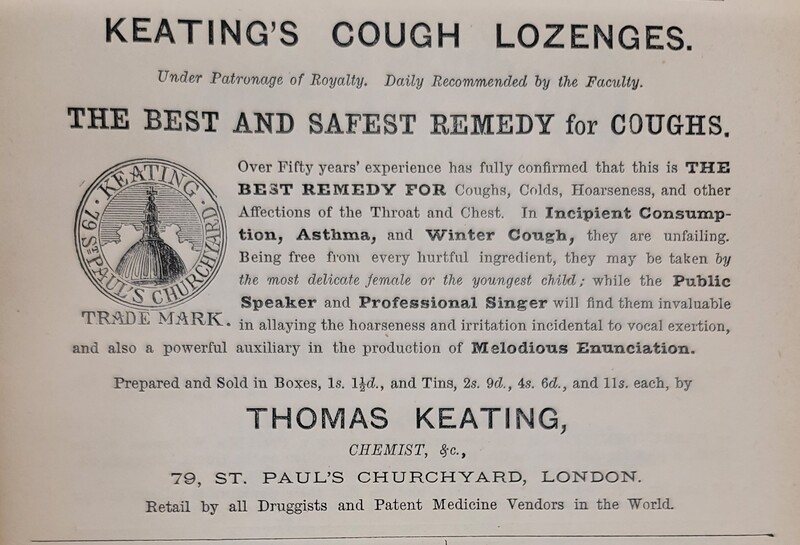

Moreover, Lydgate himself can be seen as a symbol for scientific progress and in writing such a forward-looking character, Eliot draws much attention to the benefits of medical progress since the 1830s. This affirmative “young surgeon” (Eliot 99) likely presents a sort of hope for the future of medicine to the audience of the 1870s especially when one considers the advertisements in the original parts, promising cures to all sorts of ailments. In a sense, it is understandable that the 1870s audience could find relief in ads like “Allcock’s Strengthening Porous Plaster,” “Lamplough’s Pyretic Saline,” or “Keating’s Cough Lozenges,” because it assures them that medicine is improving and its importance is being recognized. For example, “Keating’s Cough Lozenges” states that it is “free from every hurtful ingredient, they may be taken by the most delicate female or the youngest child” (Book 8, 5) which sounds wonderful enough, but the description implies that there are some medicines, likely older treatments, that did contain harmful ingredients, and maybe those sorts of harmful medicines could be present in Middlemarch’s setting. That is not to say that the ads are not misleading—or completely false quack medicines—but a Victorian audience might have found reassurance, or even pride, at the advertisements’ presence. Furthermore, the ads use language that evoke a scientific image that was meant to persuade their viewers. “Allcock’s Porous Strengthening Plaster” has three advertisements across the Middlemarch parts and each uses vivid scientific language with a specific inclination towards electricity, with buzz words and phrases like “electrical,” “electricity of galvanism,” “restore the healthy electric condition (equilibrium)” (Book 4, inside back cover), “accumulate electricity” (Book 3, 8) spread throughout the eight books. George Eliot makes similar references to electricity throughout Middlemarch and uses “electric” to often describe shock, liveliness, and energy. A passage about Will and Dorothea captures Eliot’s use of the word most fittingly:

When Mrs. Casaubon was announced he started up from an electric shock, and felt a tingling at his finger-ends. Any one observing him would have seen a change in his complexion, in the adjustment of his facial muscles, in the vividness of his glance, which might have made them imagine that every molecule in his body had passed he message of a magic touch.” (322)

This description has a strongly positive connection to electricity and “tingling” since it is physically enlivening Will and also associating scientific words, like electricity and molecule, to magic. In the same way readers would have positively viewed this passage, they would have reacted to the pharmaceutical advertisements. A similar technique is used in “Lamplough’s Pyretic Saline” in which it presents testimonials from only doctors: one Dr. Morgan, M.D., claims the saline “furnishes the blood with its lost Saline constituents,” and the late Dr. Thurley found the saline as the best and only treatment for scarlet fever (Book 4, 3). These testimonies specifically give the effect of credibility, akin to if Lydgate was recommending a treatment to the Vincys, Dorothea, or Bulstrode. Therefore, the positive scientific language of the ads, in addition to the hefty number of credible testimonies, cement to the 1870s audience that these are modern medicines that use the most up-to-date scientific discoveries, and likely would have instilled a sense of hope, comfort, and pride in their medicines compared to those in Middlemarch or the 1830s.

Lydgate and the Middlemarch Doctors

In contrast with the young surgeon, Lydgate, the doctors of Middlemarch are represented as stubborn men, stuck in their dated medical ways. To them, the worst thing a man can do “is to come among the members of his profession with innovations which are a libel to their time-honoured procedure” (Eliot 364), and that is what they feel Lydgate does: he is interrupting their status-quo by not dispensing drugs, using newer treatments and tools, and openly contradicting the Middlemarch doctors and their treatments. When Nancy Nash falls ill, Dr. Minchin diagnoses her with a tumour which would have needed to be cut out her, but when she is seen by Lydgate, he quickly corrects that she does not have a tumour, but cramps. When Nancy’s pain worsens later on, Lydgate personally sees over Nancy, continuing for “a fortnight to attend Nancy in her own home” until she recovers (Eliot 365-6). However, Lydgate’s dutiful treatment is received most negatively by Dr. Minchin, who takes personal offence to Lydgate’s interference of Minchin’s patient. Although Dr. Minchin could not complain loudly to those who were thankful for Lydgate’s help, he told the other doctors that “it was indecent in a general practitioner to contradict a physician’s diagnosis in that open manner” and that Lydgate paid no attention to “etiquette” (Eliot 366).

Like Dr. Minchin, Mr. Wrench, another Middlemarch doctor, dismisses Fred’s typhoid fever as nothing serious but for “’slight derangement’” and did not pay much attention to Fred’s treatment (Eliot 228), yet when Lydgate comes to see Fred, he immediately decides that Fred has typhoid fever and that “he had taken just the wrong medicines” (Eliot 229). However, instead of chastising Mr. Wrench for his negligence, Lydgate takes it upon himself to apologize on behalf of Mr. Wrench and makes a reason as to why he may not have correctly diagnosed Fred (229). Like Dr. Minchin, Mr. Wrench does “not take it at all well” (230). Even the way that Mr. Wrench is described by the narrator as “bilious,” and his wife “lymphatic,” signal to the 1870s audience that Mr. Wrench, and by extension the Middlemarch doctors, are scientifically behind; an 1870s audience would have an idea of germ theory, since it was gaining popularity in the mid-nineteenth century, but these descriptions recall the practice of balancing the four fluids that was dominant in 1829 and the 1830s.

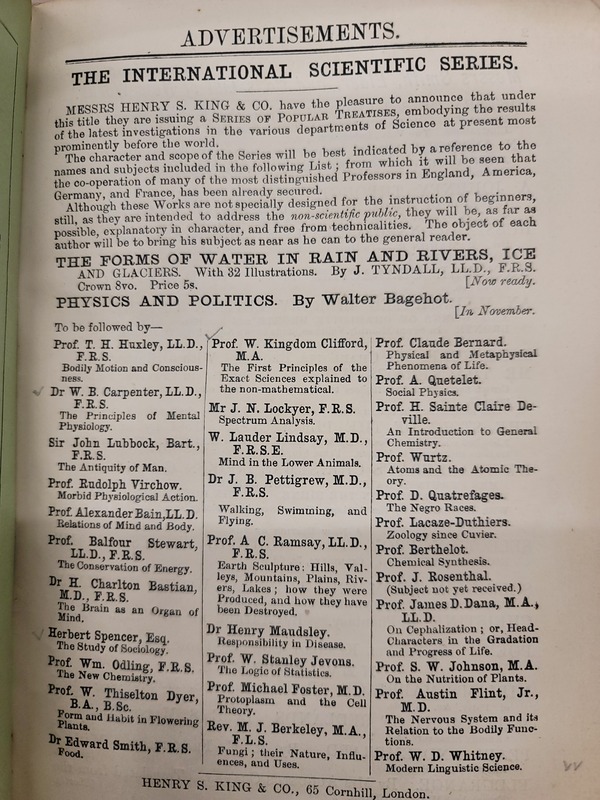

Similarly, the presence of the ad for “The International Scientific Series,” containing a lengthy list of scientific works at the beginning of Book 7, appeal to the 1870s audience because it reinforces the importance for scientific progress and education. In the context of reading Middlemarch, the ad seems to say, “buy me, read me, and become like Lydgate.” Not only does the ad recontextualize how the contemporary audience will read Book 7, but its presence reveals a general interest in scientific texts since the ad’s inclusion implies there is a targeted audience for the ad. The ad states that the series embodies “the results of the latest investigations,” and clarifies that the works are not necessarily for beginners but they are “intended to address the non-scientific public” and thus will be “explanatory in character, and free from technicalities” (Book 7, 1), emphasizing education and appealing to a wider audience.

This ad is particularly of note because it is in front matter advertisements which leads into opening line, “Have you seen much of your scientific phoenix, Lydgate, lately?” (Eliot 502) and the discussion between the Farebrother and the Middlemarch doctors over the New Hospital and cholera. More importantly, the opening chapter mentions Farebrother’s concern about Lydgate’s strange behaviour of late. In combination, the description of Lydgate as a “scientific phoenix,” the doctors’ negative comments about Lydgate, and Lydgate’s concerning behaviour communicate to readers that Lydgate may experience a burning-up (or burning-down) and a sort of rebirth. This idea unfolds over the course of Book 7, with Lydgate being implicated in Bulstrode’s scandal and ending in Dorothea’s commitment to clearing Lydgate’s name. Ultimately, this gives some justification and fervour back into Lydgate’s good scientific intentions and into the medical and scientific field. As if to emphasize this point, Book 7 closes on another ad for “Allcock’s Porous Strengthening Plaster” with a testimonial that reads that medicine “should be incapable of hurting” (Book 7, inside back cover), reinforcing in the reader that medicine—and Lydgate—is meant to be of help, providing health and security. This is again similar to the “Keating’s Cough Lozenges” ad that claims it is “free from every hurtful ingredient” (Book 8, 5) that appears in the final book of the original parts and comes at the end once the novel is complete, again cementing the achievements of 1870s medicine and progress.

The Middlemarchers

Regardless of how he is perceived throughout the novel, Lydgate persists in Middlemarch, continuing his treatment of patients and his work at the New Hospital; despite the negative comments and gossip, he also keeps presenting new or different methods in his treatment of the Middlemarchers. Lydgate’s determination to bring reform into a provincial town resembles the stubbornness of the townspeople to initially accept Lydgate. To an 1870s audience, the townspeople can represent the scientific backwardness of the 1830s but particularly of the rural crowd: the Middlemarchers take at face value the medical ideas that have been fed to them and they refuse to understand Lydgate’s different ideas and practice as beneficial to them. Rather, the townspeople demonize him, associating him with graverobbers and asserting that he “meant to let the people die in the Hospital, if not to poison them for the sake of cutting them up” (Eliot 360). It takes much convincing for Lydgate to be accepted into Middlemarch, but there are still people who hesitate or outright reject him. Mr. Mawmsey, a grocer, is one townsperson who could not personally support Lydgate because Lydgate did not dispense drugs and Mr. Mawmsey took satisfaction with buying and managing medications for his family and seeing the medications take effect (362). His wife, Mrs. Mawmsey is also reflective of Middlemarch’s medical naivety since she refers to different medicines as “the strengthening medicine” and states that “what keeps [her] up best is the pink mixture, not the brown” (363), and not the scientific name or by the purpose of their treatment. Another townsperson, an ex-client of Lydgate’s predecessor, Mr. Peacock, felt “anxiety” over not being prescribed pills, and without informing Lydgate, he gave his wife “Widgeon’s Purifying Pills, an esteemed Middlemarch medicine, which arrested every disease at the fountain by setting to work upon the blood” (365).

However, in mentioning the Middlemarchers, I have no intention to belittle or insult either the townspeople or people in the 1830s. Rather, I wish to highlight how readers in the 1870s may have perceived the Middlemarchers, especially when they are starkly contrasted to Lydgate’s superior education, admirable determination, and his great intents to bring reform to Middlemarch. I also believe that, while the ads may bring reassurance or pride for medical advancement in the 1870s, their placement throughout the original eight parts is ironic. To a more self-aware reader, perhaps the ads call into question what they are being advertised and whether they should believe it. As Gillian Beer notes, “Lydgate. . . the modern doctor of the 1830s, would still have had much to do against medical quackery in the 1870s” (19). It is very possible then that these ads reframe the narrative: although the 1870s has seen scientific and medical progress since the 1830s, there are pervading issues with medicines claiming to be cure-alls, hindering greater knowledge, progress, and ultimately health.

Conclusion

It is easy for us to look at Middlemarch’s 1870s audience and see the irony of their belief that science and medicine had greatly improved since the 1830s, but it is important to realize that, undoubtedly, 200 years from now, people will look at us and see the same irony. Regardless, it is more important that we realize how much the medical situation in the 1870s recontextualized the content of Middlemarch because it also applies to how we read and analyze historical novels. The 1870s Middlemarch readers were already familiar with medical reform and how it can improve a society, and because of the advertisements we know that readers would have thought positively about Lydgate, his achievements, and his goal. Similarly, we can assume that they thought the Middlemarchers naïve, or perhaps it was a moment of self-awareness about the quackery of the 1870s pharmaceuticals. Either way, without the ads from the original eight-part publication or without recontextualizing, we may have believed that Middlemarch readers agreed more with the doctors and Middlemarchers, and felt uneasy about Lydgate’s radical ideas. Therefore, we should consider the ramifications to us as readers, and how we should be aware of our physical space while we read and how our environment influences how we enjoy and interpret narratives.

Citation Notes

* All quotes and passages cited from George Eliot’s Middlemarch are from the 2018 Broadview Press edition.

* The images and quotes from the advertisements are sourced from The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Works Cited

Beer, Gillian. “What’s Not in Middlemarch.” Middlemarch in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Karen Chase, Oxford University Press, 2006, pp. 15-34.

Eliot George, "Book III- Waiting for Death," Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood & Sons, 1872. Vol. III of Middlemarch: a study of provincial life. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 28 Nov. 2023.https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/230c8310-087e-0133-7dba-58d385a7bbd0.

Eliot George, "Book IV- Three Love Problems," Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood & Sons, 1872. Vol. IV of Middlemarch: a study of provincial life. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1 Nov. 2023. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/37f7f7d0-087e-0133-4e77-58d385a7bbd0.

Eliot George, "Book IV- Three Love Problems," Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood & Sons, 1872. Vol. IV of Middlemarch: a study of provincial life. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 28 Nov. 2023. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/37f7f7d0-087e-0133-4e77-58d385a7bbd0.

Eliot George, "Book VII- Two Temptations," Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood & Sons, 1872. Vol. VII of Middlemarch: a study of provincial life. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1 Nov. 2023. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/8886f630-087e-0133-0bfb-58d385a7bbd0.

Eliot George, "Book VIII- Sunset and Sunrise" Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood & Sons, 1872. Vol. VIII of Middlemarch: a study of provincial life. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 28 Nov. 2023. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/a5ffc5e0-087e-0133-224c-58d385a7bbd0.

Eliot, George. Middlemarch: a study of provincial life. Ontario, Broadview Press, 2018.

Furst, Lilian R. “Struggling for Medical Reform in Middlemarch.” Nineteenth-Century Literature, vol. 48, no. 3, 1993, pp. 341-361, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2933652.