“‘I should not like to marry a clergyman; but there must be clergymen’”: The Dual Nature of Religion in Middlemarch

“‘I should not like to marry a clergyman; but there must be clergymen’”(Eliot 109). This line, spoken by Rosamond Vincy, perfectly captures the seemingly paradoxical existence of Christianity in nineteenth-century England. This era in Britain, though heir to a long and predominant history of Christianity, was a time of change for people in terms of the place that religion occupied in their personal lives. Such a phenomenon can be seen both in the text of Middlemarch, and in the paratexts surrounding it. Particularly, I will be examining Eliot’s, and Middlemarch’s, relationship to religion, as seen through the paratexts of religious advertisements and epigraphs. I argue that the paratexts help readers to understand that while Eliot was seen by many as “‘the first great godless writer of fiction that has appeared in England’” (cited in Qualls 119), Middlemarch represents not so much an outlier, a work of heathenism, as an indicator of the gradual secularization of society that takes place in the nineteenth century – in the aftermath of the Age of Reason, the Enlightenment, and consumerism – and a reflection of the dual nature of the Protestant religion as at once both ubiquitous and foundational, and largely shallow and legalistic. Religion became a framework for living a temporal life, rather than a relational and spiritual devotion transcending the boundaries of mortality.

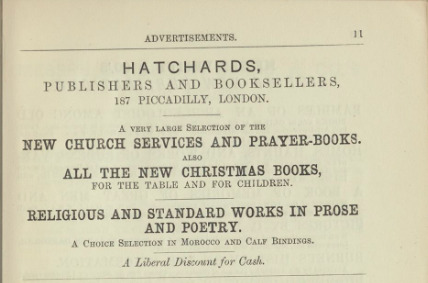

Gillian Beer notes that “[a]dvertisements are fleeting para-texts, they are absolutely ‘of the moment’ and so give a window onto the readers by whom this work was first received” (Beer 16). Advertisements, as paratexts, allow us to immerse ourselves as readers within the sociocultural context of the time in which the text was written, conveying much insight to readers about the particular values of the time. The first image I will analyze is an advertisement for Hatchards Publishers and Booksellers, taken from the first installment of Middlemarch. Hatchards was founded in 1791 by John Hatchard, a conservative evangelical. The books listed in this advertisement are various formal church books (such as church services and prayer books), Christmas books, and religious prose and poetry. Upon closer analysis, each of these types of books listed in this advertisement represents a different sphere of life, and thus speaks to the ubiquity of Christianity in Victorian life. “New Church Services and Prayer Books” represents the formal “Sunday sphere” that would have been a prominent aspect of life in nineteenth-century England. Many families attended church on Sundays and this would be a routine activity. The “Christmas Books”, noted as being “for the table and for children”, represent the domestic sphere of Victorian life. One can assume that “table” refers to the dinner table. Dinner time was an occasion where the family would gather together and perhaps there would be a reading of scripture relating to the Christmas story read before dinner. These books were also directed towards children, a fact which indicates the normalcy of catechizing children in the faith at this time. Christianity was taught from generation to generation. “Works in Prose and Poetry” represents the literary and leisurely sphere of Victorian life, these books perhaps being those that would be read for leisure. In advertising these three different kinds of books, one can infer the ubiquity of Christianity across the various spheres of nineteenth-century life. Underneath the book listings is a line stating that Hatchards has “a choice selection in Morocco and calf binding”. The fact that these books were available in high quality, durable leathers implies a greater prestige than an average paperback. From this advertisement, readers can deduce the status of religion as a permeating and undergirding force within Victorian society.

Such ubiquity of religion is reflected in Middlemarch itself. The characters dutifully attend church each Sunday, with the exception of some of the working class characters. It was part of the sociocultural norms of the age; Sundays were for church. Amidst Rosamond and Lydgate’s financial troubles – a source of great despair for Rosamond – “[o]f late she had never gone beyond her own house and garden, except to church, and once to see her papa” (Eliot 733). Rosamond, even amidst her “languid melancholy and suspense” (Eliot 733) at the prospect of her financial straits, which had left her unable to leave her house, still makes an exception for such important things as attending church. This habitual behaviour reflects the prominence of institutionalized religion in the 1830s. The prestige associated with religion found in the material composition of the religious books themselves – in the calf and Morocco bindings – is reflected in Middlemarch, through the subplot involving Fred Vincy’s career indecision throughout the novel, and his parents’ desire for him to enter the church, given that it pays comfortably and affords one a position of some esteem.

However, while the Christian religion was still a structural force within nineteenth-century England, and dutifully attended to by the people, its personal importance to the people of the time can be disputed. While the content of the Hatchards advertisement is notable in implying the predominance of Christianity in nineteenth-century English society, it is equally notable that this advertisement is the only one of its kind – occupying a half-page spread – that exists within all eight of the Middlemarch installments, which proves a seemingly contradictory point: that religion was in fact not esteemed to a position of importance to the later Victorians. All other advertisements for content related to Christianity are merely single titles scattered among many other publications offered by a particular publisher. An example of such advertisements is found in the second image, which markets Hours of Christian Devotion by A. Tholuck. The advertisement of such a book does imply the presence of Christianity in a devotional sense, but the fact that it is only one book listed alongside many published works – of heterogeneous genres including works of science, history, and literature – found in the back matter of the first book, effectively amalgamates religious texts with other kinds of books, and suggests its relative unimportance to the personal lives of most Victorians.

Understanding this seemingly paradoxical position of religion in society at the time helps readers to better understand its place in Middlemarch. While Gillian Beer argues that God is absent from Middlemarch, I would agree, but qualify this argument with the amendment that he is absent in any personal and meaningful kind of way. Particularly, and in contrast to book one, God is absent in the “Finale” of Middlemarch. “God” is mentioned once in this final chapter, when Ben tells Letty that because girls are always dressed in petticoats, they are not as useful as boys: “Letty, who argued much from books, got angry in replying that God made coats of skins for both Adam and Eve alike—also it occurred to her that in the East the men too wore petticoats. But this latter argument, obscuring the majesty of the former, was one too many” (Eliot 794). This is the only mention of God in the “Finale”. Here, Letty uses God to make a point about the equality of boys and girls. However, she uses God as just one form of evidence to prove her point, her other evidence being firmly rooted in the worldly. This suggests that God, and religion, though still a presence in the lives of Middlemarchers, are merely one framework for thinking, one option among many for looking at the world, and an option becoming increasingly obscured by the rise of alternate thought. Letty argues from books, not from religious conviction, and the Bible is just that – a book – one with perhaps a superior system of moral guidance but, nonetheless, one of many books from which one can argue about pragmatics. Though the word “God” is used sixty times throughout the novel, “religion” or “religious” used seventy-eight times, and “church” used ninety-three times, the name “Jesus” appears at no point throughout the entire novel. Jesus is the core of the Christian religion, and his role as an intermediary between man and God, as a propitiation for the sins of mankind, makes him a necessary part of the relational and grace-dependent nature of Christianity, which is absent from Middlemarch. Thus, Christianity can be seen as merely performative and shallow, though necessary structurally to society. Even Fred, who, as mentioned earlier, considers entering church ministry, ultimately only desires to go into this line of work because it is one of the few 'respectable' options for a middle class man to pursue. He laments that “‘I don’t like divinity, and preaching, and feeling obliged to look serious…I’ve no taste for the sort of thing people expect of a clergyman. And yet what else am I to do?’” (Eliot 488). Unlike what might seem to be a common conception that people go into the church for vocational reasons, Fred views it simply as a practical and performative decision, applying worldly reasoning to what has long been considered a spiritual vocation.

Analyzing the comparatively sparse advertisements for religious materials, and the content of these advertisements themselves positions an incongruity between what appears to be, and what is, the state of religion at the time. This discrepancy seen in the advertisements helps readers to understand the discrepancy found in Middlemarch itself and its own view of religion. And so while that "thoughtful and sensitive young man”, mentioned in Scribbner’s Monthly, who, upon finishing Middlemarch may have cried out despairingly “‘'My God! And is that all?’” (cited in Carroll 30), he was not encountering a wholly novel phenomenon in experiencing literature that was far from God; rather, the advertisements help the reader to understand that this paradoxical and dual existence of religion in Middlemarch was merely a literary representation of a secularizing age, where religion, though occupying a foundational space in society, was often performative and superficial, and was becoming increasingly obsured by other kinds of knowledge.

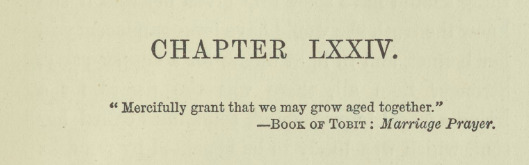

The third image is of the epigraph for chapter 74 of Middlemarch, found in the final book, and is taken from the book of Tobit, a name likely unfamiliar to most Protestant ears. Tobit is considered among the canonical books of the Catholic bible but is not considered canon among Protestants, being excluded from the Protestant bible but acknowledged as part of the apocrypha. It is noteworthy that Eliot here engages with Catholic religious reference, particularly given the Catholic question of the time, and the Protestant affiliation of the characters in Middlemarch. There are many bible passages on marriage that George Eliot could have drawn from, so it is particularly noteworthy that she instead opts to include a passage about marriage that was considered extra-canonical by most. The fact that Eliot engages with such material is evidence of the progressive secularization of society and the diversification of religiosity that occurred over the course of the nineteenth century. The seeming paradoxicality of this situation is actually intentional. Eliot is writing towards the end of the nineteenth century during a time of considerably more religious freedom. Middlemarch itself, however, is set during a much more religiously tumultuous time. The end of the nineteenth century was characterized by greater diversification of religion that was not present in the 1830s, when the “Catholic question” was still very much a prominent issue. The fact that Catholic reference is used here reflects a certain ambivalence towards the notion of one religion as the right way.

The Catholic question is a frequent topic of discussion among Middlemarchers. Mrs. Cadwllader tells Mr. Brooke at one point that “I shall inform against you: remember you are both suspicious characters since you took Peel’s side about the Catholic Bill” (Eliot 48). Such a comment, said partly in jest, exemplifies the religious tension that existed at the time. Though most Middlemarchers held a fairly progressive stance on the Catholic Question, that there was such a Catholic question to even be considered demonstrates that there was a tension between religious factions in the 1830s, a tension that had been considerably mitigated by the time George Eliot writes in the 1870s. As such, the paratext reflects the changing role of the Protestant religion during the time that Middlemarch is set, illustrating the shift away from Protestantism as the only form of religion that could exist, a shift that was more fully realized in the 1870s.

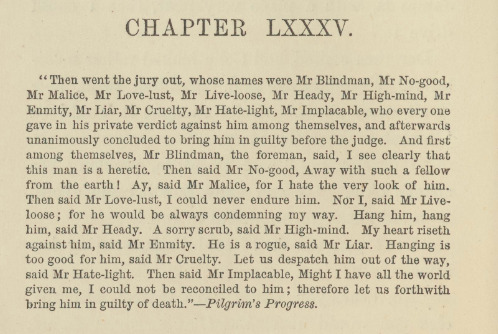

The fourth image is of the epigraph for chapter 85 of the novel, found in the last book. The Pilgrim’s Progress was published in 1678, two hundred years prior to the publication of Middlemarch. Yet, it would have still been considered an influential work in the nineteenth century. The Pilgrim’s Progress at one point in history was second in popularity only to the Bible. It is the most famous Christian allegory. This use of this text as an epigraph for this particular chapter, which focuses on Bulstrode, is both fitting and jarring. It is fitting that such an epigraph should be used here, because of Bulstrode’s ostensibly devout religiosity, and yet it is jarring given that he has proven himself quite impious in his conduct. The epigraph serves to highlight Bulstrode’s own guilt in light of his self-pitying nature, by juxtaposing him with Christ’s innocence and martyrdom, particularly given the fact that Bulstrode would quite like to see himself as a righteous, Christ-like figure.

Bulstrode is introduced as a devoutly religious man with deep convictions and a disdain for things that do not serve God’s glory. Known for both his legalism and proselytism, he disparages many of the “sinful” activities of Middlemarchers far less pious than he. When Vincy approaches Bulstrode to ask for help regarding the securing of Fred’s inheritance, Bulstrode tells Vincy that “‘I am not at all sure that I should be befriending your son by smoothing his way to the future possession of Featherstone's property. I cannot regard wealth as a blessing to those who use it simply as a harvest for this world…I do not shrink from saying that it will not tend to your son's eternal welfare or to the glory of God” (Eliot 121). He decries what he sees as Vincy’s “‘worldliness and inconsistent folly’" (Eliot 120). He is full of what appears to be religious zeal. And yet there is no substance to his faith, which he utilizes to justify his own selfish actions. It is not, then, to be overlooked that "Providence'' becomes the catalyst for his own undoing. It is “Providence'' that brings Bulstrode into the sight of the gathering Middlemarchers outside of the Green Dragon, causing a series of remembered and interconnected memories shared between the group, allowing them to weave together a narrative that indicts Bulstrode in the murder of Raffles. Bulstrode is undone by the very faith he used to place himself above others and further his own material success. As a result of his fall from grace, “[h]e felt himself perishing in unpitied misery…And if he turned to God there seemed to be no answer but the pressure of retribution.” (Eliot 715). Though God began a main feature in Bulstrode’s life, one he used for his own gain, God is absent in the life of Bulstrode at the end of the novel. Though religion seems to be the backbone of Nicholas Bulstrode, it is simply a tool used by him to serve himself, not an enduring belief and devotion. There is a discrepancy between what appears to be, and what is, in the case of Nicholas Bulstrode’s religion, and the use of an epigraph taken from one of the most famous Christian books, serves to highlight to readers the incongruity in Bulstrode's spiritual life.

Such a discrepancy illustrated in the advertisements, epigraphs, and life of Bulstrode, can also be seen within the character of Dorothea. Dorothea, in the opening chapter of the first book is characterized by her "Puritan energy" (Eliot 5). Throughout the first book she is defined by her adherence to a strict religious code, denying worldly pleasures in pursuit of divine greatness. She desires to do great things, to be a “Saint Teresa” of sorts, and yet her religion seems to be defined less by a devotion to God and an evangelistic understanding of Christianity, being instead rooted in a desire to “do good” in society, certainly a tenet of Christianity, but not one that separates the believers from the unbelievers. Dorothea has a passionate devotion for social justice, but this is not equivocal to a personal faith. Rather, she utilizes religion as a moral framework that guides her life, but ultimately her true devotion is to the bettering of the lives of those around her. She is consumed and defined by piety and religiousness in book one, but beginning in book two we see the decline of its prominence in her life. She never attains the greatness that she so aspires to, instead becoming disillusioned with the spiritual and drawn in by the erotic. After realizing that she is in fact in love with Will Ladislaw there

came the hour in which the waves of suffering shook her too thoroughly to leave any power of thought. She could only cry in loud whispers, between her sobs, after her lost belief which she had planted and kept alive from a very little seed since the days in Rome after her lost joy of clinging with silent love and faith to one who… was worthy in her thought after her lost woman's pride of reigning in his memory-after her sweet dim perspective of hope, that along some pathway they should meet with unchanged recognition and take up the backward years as a yesterday. (Eliot 749)

Dorothea, for all her purity and gentleness of spirit, does not demonstrate a devotedness to God in any sense other than a dutiful desire to carry out social justice initiatives and fulfill her duty as a wife. As the novel progresses, she comes to terms with the fact that she must “endure her own typicality” (Beer 28). As she does this she becomes less rooted in her piety and espoused spirituality, and more rooted in the temporal and material.

Elaine Freedgood argues that “[l]ike many other characters in the novel who must learn how to have a realistic, or perhaps a real-ist, relationship to money, Dorothea enacts the bildung not so much of the post-Enlightenment individual, but of the modern consumer. By novel's end, she clinches her avowal of love to Will Ladislaw with a promise to learn the ropes of commodity exchange” (Freedgood 119). Dorothea by the end of the novel is less concerned with spirituality as she is with the pragmatics of a material life, one that is lived well, but a material life nonetheless, a shift that reflects the progression of the consumer society in England throughout the nineteenth century. With Dorothea, as with Bulstrode, there is a divergence between a surface reading of the text and a close reading, between what seems to be, and what is, the state of religion in the heart. Such a discrepancy is reflected in the epigraphs themselves when read in light of the characters’ journeys. At first glance, a reader may think it absurd that as Gillian Beer claims "God is absent from Middlemarch"(Beer 26) . God is everywhere in Middlemarch. And yet he is nowhere to be found. Just as the impression of the predominance and significance of Christianity to the Victorian people that is seemingly inferred from the Hatchards advertisement is mitigated by the comparative silence on this concept in advertisements for the rest of the books, the religious fervour seemingly characterizing Middlemarch’s two most religious characters is undercut by the actions they commit and the realizations they come to.

The eighteenth century saw the progression of philosophy and science and its shift to the forefront of society, offering ways of explanation of the world that replaced traditionally religious conceptions of the world, and leading to religious declension. Christianity was predominant at the start of the nineteenth century but by the end of the nineteenth century it loses its status as such. Perhaps the declension of religion in Middlemarch from beginning to end (particularly in the lives of Bulstrode and Dorothea) parallels the declension of religion in England between the time Middlemarch is set and the time Middlemarch is written. Especially given that the finale takes place years into the future, it is possible that the finale reflects the state of Christianity within Eliot’s contemporary sociocultural context.

Middlemarch offers a complex understanding of religion, reflective of Eliot’s own relationship with religion. Thomas Carlyle calls Eliot "‘the emblem of a generation distracted between the intense need of believing and the difficulty of belief’" (cited in Qualls 119). Bernard Paris writes that “[a]fter her rejection of Christianity in the early 1840's, Eliot still lived in a universe which was divinely sustained and directed; and although she no longer believed in personal immortality, she still felt that man's spiritual nature linked him to God” (Paris 418). Eliot, though lacking personal faith still utilized religious texts in her works. Middlemarch is not a manifestation of some cultural anomaly, reflecting the beliefs of a deviant woman in a devoutly religious society. The advertisements, and their comparative lack of dominance amongst the paratext of Middlemarch, as well as the epigraphs and their incongruity with the lives of the characters’ stories they surround, prove that Eliot and Middlemarch were, in part, merely a product of a diversifying society, one that disputed the notion that there was one way to God.

Religion in Middlemarch is not a promoted way of living predicated upon a belief in a saving faith and eternal life, and a subsequent devotion to God. It is instead performative, used by characters as an ethical framework for living, that is often undermined by the characters own actions and desires. The characters go to church and say their prayers, but they are not spiritually moved or affected by their faith. Analysis of the paratexts reveals to readers that the seemingly paradoxical nature of Christianity in Middlemarch is merely a reflection of the way that Christianity came to be viewed in nineteenth-century England by the public: as a ubiquitous, foundational legalistic and ethical framework, rather than a relational and spiritual devotion. Thus, God is everywhere in Middlemarch, and nowhere at all.

Works Cited

Beer, Gillian. "What's not in Middlemarch". Middlemarch in the Twenty-First Century. Ed. Karen Chase.

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Carol, David, ed. George Eliot: The Critical Heritage. Routledge, 1971.

Eliot, George. Middlemarch. Modern Library, 2000

---. “Miss Brooke”. Edinburgh and London. William Blackwood & Sons. 1871. Web. Vol. 1

of Middlemarch: A Study in Provincial Life. 8 Vols. 1871-1871. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/e9ea0c80-087d-0133-420f-58d385a7bbd0#/?uuid

ea83be60-087d-0133-f4d3-58d385a7bbd0

---. “Sunset and Sunrise”. Edinburgh and London. William Blackwood & Sons. 1872. Web.

Vol. 1 of Middlemarch: A Study in Provincial Life. 8 Vols. 1871-1871.

https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/9d3e0410-087e-0133-8ded-58d385a7bbd0

Freedgood, Elaine. “Toward a History of Literary Undetermination: Standardizing Meaning in

Middlemarch”. The Ideas in Things: Fugitive Meaning in the Victorian Novel. University of Chicago

Press, 2006.

Paris, Bernard. "George Eliot's Religion of Humanity". ELH. Vol. 29, no. 4. Baltimore: Johns

Hopkins University Press, 1962.

Qualls, Barry V. “George Eliot and Religion.” The Cambridge Companion to George Eliot, Cambridge

University Press, 2019, pp. 195–214, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108147743.012