Introduction

My digital project focuses on Mr. Casaubon’s death scene in Middlemarch’s fifth book. The project also uses textual examples of Casaubon in his estate’s garden, as seen in book four. My assessment of the novel’s garden scene connects to the advertisements from the original publication of Middlemarch’s book four and five. The advertisements and the unique focalization on Casaubon’s estate garden connects to Eliot’s interest in botany, mythology, and specifically the ancient yew tree.

The Victorian garden – and the greater influences on British landscaping – privileges aestheticism with particular investment in patriarchal representations of status, especially pruning and botanical arrangements displaying men’s ability to tame their natural environment. While gardens are commonly represented as a feminized domestic space, the Casaubon estate garden is physically and metaphorically penetrated by one man, Casaubon himself. Interestingly, Eliot’s descriptions of Casaubon’s garden lack reference to all flora and fauna. In fact, the only plant named in the Casaubon’s garden space is the “yew-tree Walk” (347) that surrounds the seating area of the garden. The yew tree is explored as an object symbolically connecting to Mr. Casaubon’s death.

Elaine Freedgood provides historic contextualization for the progression of scientific study in the Victorian era, writing that “ancient Greek” literature and “British forest trees” were among Eliot’s extensive range of “reading and research interests” (111), aiding in Eliot’s access to class mobility through her intellectual accomplishments. Additionally, Gillian Beer writes that the “… absence in the book’s subject matter… [especially] the death of loved people” (16) is a narrative boundary Eliot establishes. “The three deaths that propel the plot are all of dislikeable people” (Beer 16), showing their narrative purpose in Middlemarch. Casaubon’s fate is instrumental in shaping Dorothea’s remarriage plot.

Lauren Hoffer theorizes that “[f]or a culture deeply invested in inheritance, a character’s death is often significant in that it can free a particular fortune or living into circulation within a community, usually prompting contention that further drives the narrative forward. Similarly, the death of a married character returns the surviving spouse to the sexual economy, generating new and distinct possibilities for courtship and remarriage” (45).

Hoffer’s theory, when specifically attached to Middlemarch’s primary married couples, suggests death as one of the novel’s sources of narrative movement. Literary scholarship continues to “illuminate the social realities of remarriage in the nineteenth century, including its ideological implications, through a prism of invaluable studies on bigamy, divorce, widows, and widowers” (Hoffer 46). This statement suggests that the “ideological implications” of Dorothea’s remarriage plot are mobilized through Casaubon’s death. Additionally, the revealed terms of the codicil reinforce Dorothea’s politically complex status as a widow by returning her as a sexual commodity to the capitalist marriage marketplace.

My assessment of Middlemarch’s depictions of marital realities in the Victorian era attempts to extend previous arguments from Elaine Freedgood and Gillian Beer, exploring how objects in the novel propel the narrative forward. My chosen images attempt to address the symbolic, aesthetic, and literary connection between Mr. Casaubon’s death and the yew tree. The sections of Middlemarch leading to his death provide insight into the scientific and literary changes occurring in the nineteenth century and British readership’s associated knowledge. Furthermore, this project argues that the original publication of Middlemarch, and the advertisements featured in the novel’s sections that lead to Casaubon’s death, provides further access into the perspectives of nineteenth century British readership and the cultural, political, and symbolic associations that arguably influenced their gardening aestheticism. Eliot’s baren description of the Casaubon’s estate garden, and Casaubon’s unnatural ‘penetration’ of the traditionally feminized garden, further suggests his narrative purpose.

Illustration: Introduction

The illustration shows an arched patio space on a country estate, with a man seated and watching the horizon. Below the chapter title “Introduction” a quote from Lowell reads, “The landscape, forever consoling and kind, / Pours her wine and her oil on the smarts of the mind” (Scott 11). Victorian Gardens: The Art of Beautifying Suburban Home Grounds (1870) provides nineteenth century homeowners with instructions to enhance the exterior of their private, domestic homes. The book’s introductory content provides contextualization for nineteenth century garden aestheticism and the prevalent cultural expectations for displaying wealth using the exterior of domestic spaces.

The British preoccupation with garden aestheticism became increasingly accessible to middle-class men in the Victorian era. “The arts of arrangement” (Scott 12), while associated with feminine preoccupations, was highly influential on Victorian men’s performance of masculinity and their cultivation of power. The image of the solitary man connects to Eliot’s descriptions of Casaubon in his estate garden. The Casaubon estate is symbolic of Victorian prosperity and success. Middlemarch presents a unique garden by eliminating all reference to life, fertility, and growth, instead showing Casaubon sitting in isolation. Middlemarch’s two significant garden scenes show Mr. Casaubon being discovered by Dorothea – first, with him alive and, second, with him dead.

Hoffer argues that Middlemarch “reinforces the death of Dorothea Brooke’s first husband in order to signal the reopening of fresh narrative possibilities, to frame Dorothea’s second marriage as consequential” (47). Unlike Scott’s image of the solitary, successful Victorian man, Casaubon’s success is overshadowed by his being “marked… for death from” the novel’s earliest descriptions of him (47). Eliot ensures his deathly association is consistent, making the discovery of his body a reflection of his failed project – The Key to All Mythologies. Dorothea finds Casaubon dead, with his scholarly robes, “wrapped in a blue cloak, which, with a warm velvet cap, was his outer garment on chill days for the garden” (Eliot 389-90). Here, his lifeless form is compared to the book itself using the descriptions of rich fabric.

Hoffer further states, “Casaubon is associated with the past and fatality both through the nature of his work and his aged, sickly body. The narrator’s treatment of him suggests his very purpose in the narrative is, in fact, to die” (47). The novel reinforces Casaubon’s embodiment of dead ideas and resistance to progress. For 19th century readers, they were likely in suspense with each book’s release, anticipating his death and Dorothea’s remarriage.

Advertisement: Books on Gardening

This advertisement for “Books on Gardening” lists recent publications on gardening, botany, and horticulture. The listed works display the late Romantic and Victorian publication of gendered educational books. The natural sciences, while dominated by men, advertised botany a feminized natural science interest to which women were allowed to pursue as hobbies within their domestic homes.

The advertisement features flower-garden, tree, food cultivation, and bee keeping “handy-books” or “handbooks” (book 2, 14). The advertisement hints toward the rise in scientific progress, as well as the development of strong categorizations of plants, animals, and humans. The first book, “A Handy-book of the Flower-Garden,” describes the content as “Directions for the Propagation, Culture, and Arrangement of Plants in Flower-Gardens all the Year Round; embracing all Classes of Garden, from the largest to the smallest” (book 2, 14). The use of “Classes” to describe variations of plants and landscaped spaces themselves aligns with late nineteenth century scientific theorizations that instrumentally impacted social, political, and cultural developments in England.

Judith Page and Elise Lawton Smith argue Romantic and Victorian era women writers “used the subject matter of gardens and plants to educate their audience, to enter into political and cultural debates, particularly around issues of gender and class, and to signal moments of intellectual and spiritual insight. As more women became engaged in gardening and botanical pursuits, the meanings of gardens – recognized here both as actual sites of pleasure and labor and as conceptual or symbolic spaces – became more complex” (1). Women writers from the Victorian era, much like Eliot, describe home landscaping spaces to function “as a transitional of liminal zone” (Page and Smith 1). This connects to Casaubon’s repeated placement in the garden as foreshadowing his death because it suggests Eliot’s contemporary readership was familiar with the liminal state of gardens in literature, either representing an idyllic space of fertility (3), or one that signifies risk, fate, and even death.

The feminization of botany and ornamental flower gardens is echoed throughout Middlemarch. After Dorothea’s engagement to Casaubon, and in his excitement over her “characteristic excellences of womanhood” (Eliot 67), Casaubon tells Dorothea, “I have been little disposed to gather flowers that would wither in my hand, but now I shall pluck them with eagerness, to place them in your bosom” (67). This statement not only indicates Victorian practices of masculinity and men’s discomfort with feminized objects, but the violence suggested by his ‘eager plucking’ of a sexually associated plant. Casaubon’s baren garden space connects to his anxiety over touching and withering the delicate flowers – a metaphoric extension of Dorothea’s body. Eliot uses flowers to engage with the realities of women’s marital duties, and Casaubon’s sexual rights to Dorothea’s body after their wedding.

Main Text: Decorative Planting

The chapter “Decorative Planting” reflects Victorian developments of scientific diction, instead using poetic language to describe plants, especially before scientific inventions like the modern microscope. Scott encourages male audiences to display wealth using the aesthetic beauty of “the endless variety” of trees (72). Scott asserts the importance for men to enhance the home’s visual excellence. The trees, “and their shadows, which play with the sunlight and moonlight on the grass beneath them” (72), are described as creators of art.

Elaine Freedgood states that “the standardization of meaning is a central project of Middlemarch” (117). She further writes that “Eliot… was among the first novelists to decide that the stuff, that is to say the things, of everyday life could have meanings for readers that narrators ought to restrict by way of interpretation” (117). Freedgood’s argument aligns with my analysis of gardens, especially leading to Casaubon’s death. The complex yet standardized meaning of objects that Freedgood describes is connected to the novel’s specific mention of one tree species. The yew tree’s singular presence in Casaubon’s garden amplifies the lack of colour, vibrancy, and ornamental variations of flowers.

The textual examples from “Decorative Planting” suggests a greater cultural relevancy of sharing information using artful language, perhaps simply because scientific terminologies were developing and continuing to shift in the late nineteenth century. Freedgood articulates that “the writer must ‘translate’ the world rather than copy it” (118) and is useful for understanding Eliot’s realist narrative strategies. Regarding Casaubon’s death, the garden’s absence of botanical beauty ensures readers recognize the reoccurring presence of “dark yew trees” (Eliot 349), and the “Yew-tree Walk” where Casaubon frequents to exercise (347).

The absence of description propels readers towards culturally significant symbolism. Beer addresses this as the novel’s calling “on a stock of common knowledge – that is to say, knowledge common to its first readers” (Beer 15). I argue that the yew tree, and its historic symbolic meaning on the British Isles, would be recognized by conventional readers. Yew trees were popularly addressed by famous writers like Shakespeare and Wordsworth, whose poetry meditates on the metaphoric, aesthetic yew.

Advertisement: Popular Works of Natural History

Unlike the “Books on Gardening,” this advertisement for “Popular Works of Natural History” focuses on broader subjects of biology, botany, zoology, and geology (book 2, 15). The advertisement is marketed primarily “for the use of students” (book 2, 15) studying these subjects, showing both class- and gender-based issues with public access to scholarly information. This image also suggests Victorian readers conventional knowledgebase, specifically for middle- and upper-class citizens. Many of the Middlemarch characters have political opinions, economic and political stakes in the ongoing British reforms that threaten the traditions of provincial life in Victorian England. Characters like Lydgate and Ladislaw challenge convention in Middlemarch, while Casaubon embodies old knowledge associated with historical, patriarchal Englishness. He is positioned in contrast to younger male characters pushing for scientific, political, and cultural change.

The historical, botanical, political, and metaphysical yew tree is explored in Fred Hageneder’s Yew. The yew tree, or taxus baccata, is described as one of the oldest on earth with first records dating back “fifteen million years ago” (Hageneder 16). Yews are significant to the British Isles, being the “only native evergreen tree surviving in Britain today” (18). From the Renaissance into the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the “aesthetic yew” became an interest to aristocrats and noble landowners to aesthetically represent pleasure and status (Hageneder 114). The aesthetically altered, clipped, and shaped yew further signifies the patriarchal desire to control nature (115).

In book four, Casaubon is first described in the garden as a “black figure with hands behind and head bent forward continued to pace the walk where the dark yew-trees gave him a mute companionship in melancholy” (Eliot 349). Significantly, only yew trees are mentioned amongst many variations of other trees. The narrator then states, “Here was a man who now for the first time found himself looking into the eyes of death” (349), continuing the association between Casaubon, the garden, and his fate.

The novel’s description of Casaubon as having “mute companionship in melancholy” (Eliot 349), contrasted against the yew trees and their aesthetic associations, heightens our perception of Casaubon’s fragility and, presumably, his infertility while married to Dorothea. The garden’s function as “mute companionship” is further suggested by the space’s unnatural silence, while most literary descriptions of gardens focus on sensory details that signify fertility and prosperity. The advertisement “Popular Works on Natural History” connects to Casaubon’s scholarly pursuits, showing new theories being produced by historically male scholars and scientists. The advertisement only lists male authors for all academic books used in natural science disciplines. Casaubon’s subversive presence in the lifeless garden alongside the advertisement’s Victorian scientific ideas, further shows his association with historic intellectual Britishness.

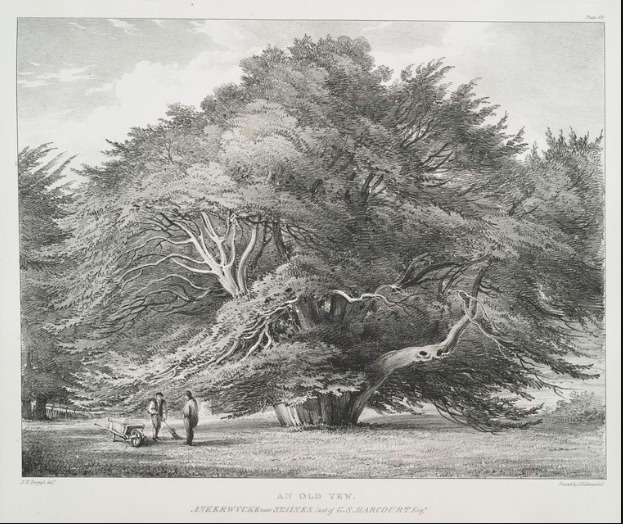

An old Yew, Anckerwycke nearStaines, Seat of G.S. Harcourt Esqr.

“Ancient Classics for English Readers” suggests the mid-nineteenth century’s rise in middle-class literacy. With the increasing availability of cheap books, middle- and working-class citizens experienced greater literacy and interest in accessing classical literature. The advertisement suggests a growing civilian knowledge of ancient Greek and Roman myth – a subject that connects to Mr. Casaubon’s scholarship.

This advertisement is important by showing the current publications of ancient Greek and Roman plays that significantly shape Eurocentric ideas, cultural practices, and politics. Homer’s The Iliad and The Odyssey, for instance, is followed by this review: “It cannot be doubted by any thoughtful man… that this series is destined to play a more prominent part in the history of our literature… The signs of the times point a diminution of classical study, but with such a series as the one before us, the interest in classical lore will be increased” (22). This review suggests that Eliot’s contemporary readership would have oral and literary knowledge of ancient mythology, and that Victorian productions of cheap literature created greater access to culturally entrenched myth and symbolism.

The second image in this showcase, of an old yew in Britain, was created shortly before Middlemarch’s publication. Yew trees are strongly associated with ancient mythology and were often representative of immortality (Hageneder 122) until the “seventeenth and eighteenth centuries” when “the yew became known as the ‘tree of death’ (122). The reason for this association is the tree’s primary presence in graveyards where they were protected from deforestation (122). This evidence indicates that Eliot’s readers would commonly associate the yew tree with an omen of death, not knowing the yew tree’s negative association was made two hundred years earlier. The tree’s dual representation as immortal by ancient myth and as the ‘tree of death’ by Romantic and Victorian writers makes its aesthetic, political, and metaphysical power more interesting. My inquiry into Eliot’s use yew trees expands on Gillian Beer and Elaine Freedgood’s analysis of objects in the novel, suggesting the mythical (and botanical) tree reinforces a standardization of meaning surrounding Casaubon’s death.

The advertisement for ancient classics thematically relates to Casaubon’s project, The Key to all Mythologies. Molly Clark Hillard points towards the novel’s refusal to overtly explain his book, theorizing that “His project, then, is to uncover the single, universal origin of all cultural tradition and to prove that the world degenerates from grand mythic narratives to fragmented fairy tales. Given this precis, one wonders why no critic has called Casaubon a folklorist” (61). Hillard’s summary of Casaubon’s book, using the novel’s pieced information from Casaubon and the narrator, shows the absurdity of his project’s ambition. In attempting to discover the “universal origin of all cultural tradition,” Casaubon becomes representative of the English literary canon, traditions of masculine Britishness, and a generational resistance to scientific, social, and political change.

Even his scholarly robes, “a blue cloak… with a warm velvet cap” (Eliot 389-90), is significant as the scholarly language used to describe his work is used to describe his now dead body, meaning that The Key to all Mythologies “fully extends to embody his person” (48). Hillard’s idea that his unfinished work is represented by his dead body, personifies a physical object that is consistently presented in the novel. Hillard further echoes observations of other Middlemarch scholarship, stating that “even after his death, Dorothea views Casaubon’s works, defined here as relics of the past in and of themselves, as vestiges of him with which she will have to contend long after he is gone” (48). His body being viewed by Dorothea is significant by bringing her painful understanding that his death marks her life-long devotion to his book.

Conclusion

Middlemarch explores symbolic imagery through repeated use of objects that hold consistent meaning. My investigation attempts to extend the arguments made by Freedgood, Beer, and Hoffer, further connecting Casaubon’s presence in the garden to significant objects that propel the novel’s remarriage plot forward. Casaubon’s relational identity with the ancient yew tree establishes a consistent pattern of association in Middlemarch’s book four and five, encouraging an anticipatory response from readers. His narrative purpose is arguably to die, and the mythical yew’s particular nineteenth century association with death supports this idea. Eliot’s standardizations of meaning are deplored through objects that held particular interest for her intellectual studies. Ancient trees and classical literature are significant symbols to which Casaubon, and The Key to All Mythologies, is associated. While it is unclear whether Eliot’s contemporary readers would understand Eliot’s use of the mythical yew, my project attempts to provide further insight into Victorian experiences of handling and reading the original eight books of Middlemarch.

Works Cited

Beer, Gillian. “What’s Not in Middlemarch,” Middlemarch in the Twenty-First Century, Oxford University Press, 2006.

Eliot, George. Middlemarch. Ed. Gregory Maertz. Broadview Press, 2004.

__. Middlemarch: A Study of Provincial Life. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood & Sons, 1871. 8 vols. 1871-1872. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 27 Nov. 2023.

Freedgood, Elaine. “Toward a History of Literary Underdetermination: Standardizing Meaning in Middlemarch,” The Ideas in Things: Fugitive Meaning in the Victorian Novel, University of Chicago Press, 2006.

Hageneder, Fred. Yew. Reaktion Books, Limited, 2013. ProQuest Ebook Central, Accessed 25 November 2023.

Hillard. “Antiquity, Novelty, and The Key to All Mythologies,” Spellbound: The Fairytale and the Victorians, The Ohio State University Press, 2014.

Hoffer, Lauren N. “‘A Beginning as Well as an Ending’: The Narrative Power of Death and Remarriage in Middlemarch,” Studies in the Novel, vol. 54, no. 1, 2022.

Page, Judith W., and Elise Lawton. Smith. Women, Literature, and the Domesticated Landscape: England’s Disciples of Flora, 1780-1870. Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Scott, Frank J. (Frank Jesup). Victorian Gardens: The Art of Beautifying Suburban Home Grounds. D. Appleton & Co, 1870. Biodiversity Heritage Library, 28 Nov. 2023. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.53772.