Sewing the Narrative Fabric: Navigating George Eliot's Masterpiece Through the Intricate Threads of Society and Technological Transformation

Reflecting on the significance of engaging with the original publication of Middlemarch, the sentences by Eliot herself in Essays of George Eliot sound as a fitting response and rationale in this regard, that “… it is often good to consider an old subject as if nothing had yet been said about it; to suspend one’s attention to revered authorities and simply ask what in the present state of our knowledge are the facts which can with any congruity be tied together…” (Eliot 431). In contemplating the justification behind revisiting Middlemarch, only this time with a digital dimension at work, I have chosen to focus on the enduring themes of the textile industry, needlework, costume, and sewing as the "old subject" deserving further elaboration within the eight volumes. I am intrigued by how the advertisements in the original publication, particularly those featuring sewing machines and silk products, might provide contemporary readers with insights into their impact on the novel's initial readership in 1871 about femininity, gender roles, and technological transformation. The advertisements, consistently absent in the current version and also excluded from the four-volume edition of the novel, as elucidated by Gillian Beer, serve as a shared plane of expectation and necessity connecting the writer with the initial readership. It is crucial to discern that, in delineating needs, advertisements not only underscore satisfaction but also bring to the forefront a sense of inadequacy and yearning. They draw attention to realms of awareness that were then numbed by habitual familiarity. Additionally, they possess the capacity to pinpoint subtle shifts that might escape casual observation but were collectively experienced without explicit commentary by Eliot and her original readers (Beer 24).

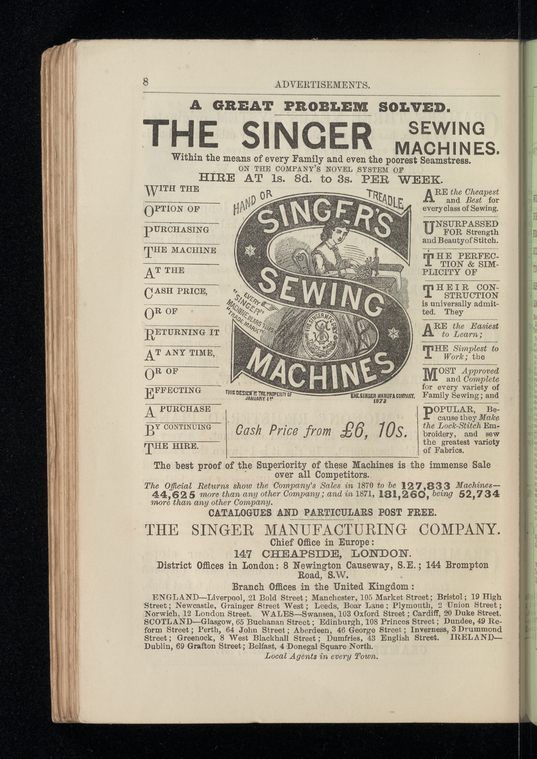

Although needlework and sewing are evident pursuits among different characters in the novel (and women of that era in general), notably Mary, as portrayed in the passage "She was now in her usual place by the fire, with sewing in her hands and a book open on the little table by her side" (Eliot 133), and Rosamond, who is observed "beginning to sew again automatically" (Eliot 584), the manner and regularity with which this engagement is depicted plays a pivotal role in distinguishing the characters and elucidating their social status. More specifically, not only does Mary's frequency of engaging in sewing surpass that of Rosamond, but the text establishes that Mary pursues this activity as a means of livelihood, embodying the "self-sacrifice that her [Eliot’s] major female heroines must undergo" (Thierauf 481). In contrast, for Rosamond, sewing remains a leisurely pursuit, contributing to her symptoms of "arriviste determination" and cultivating an air of femininity in accordance with societal expectations (Thierauf 486). The distinction in purpose and concern becomes particularly evident in the text itself, as evidenced by Rosamond's emphasis on entrusting Mary with the substantial part of her trousseau, extolling Mary's sewing prowess as "exquisite" and affirming, "it is the nicest thing I know about Mary" (Eliot 289). At an additional level, this distinction is further underscored through advertisements, exemplified by the one above, which expressly targets “poor seamstresses.” This underscores not only the designation of the sewing machine and, by extension, the vocation for women but also stresses its utilitarian essence, portraying it as a means for impoverished women to extricate themselves from adverse socioeconomic conditions.

Thus, the advertisement, with the bold title of “A GREAT PROBLEM SOLVED,” contributes significantly to the dual strata of gender-specific habitual ignorance, encompassing the perception of sewing as a pursuit for women (gender) and, concurrently, as an occupation for impoverished women (socioeconomic status). This nuanced aspect and ignorance, which was "never placed at the center of concern for any of the prominent characters in the novel" (Beer 23), runs counter to Eliot's presumed intentions for her narrative. This is the realization that we have come to now, but may have eluded the original target readers due to the influence of the advertisements, a disadvantage that is more transparent to contemporary readers of the novel. In other words, the sewing machine and its products (dress, accessories, etc.) could be viewed in light of what Flint underscores as the prevailing interplay of aesthetics and morality in the novel’s context. Eliot's treatment of materiality within the novel transcends superficiality, instead harnessing the potential of material objects at the service of morality, didacticism, and aesthetics (Flint 66-67) and going beyond a mere functional activity to reveal deeper social, economic, and cultural implications.

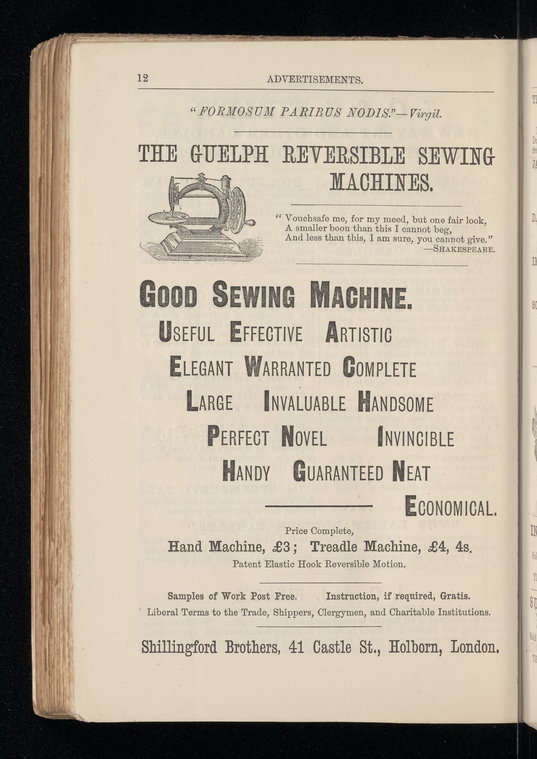

Additionally, the advertisements featuring the sewing machine contribute to a more elucidating portrayal of the profound changes ushered in by technological advancements and the inherent convenience they naturally introduced into the daily lives of individuals who, due to the habitual nature of their existence, remained largely unaware of such progress or perhaps even scarcely recognized themselves as deserving of it. Although Barthelemy Thimonnier, a French tailor, conceived a sewing machine utilizing a hooked needle and a single thread, thus pioneering the chain stitch in 1830 (Lo), it was not until the late 1840s that the sewing machine, resembling those in contemporary times, was developed and subsequently entered mass production only in the 1860s and early 1870s. According to Beer, the manual sewing practices depicted in the novel, characterized as "decorative by Rosamond and utilitarian by Mary Garth, and from which Dorothea is exempted by her short sight" (Beer 24) are very well juxtaposed in the initial presentation of the novel with the advertisement for the Guelph Sewing Machine provided above. Guelph, a Canadian manufacturer, introduced machines that were cutting-edge in England in 1871. This advertisement, therefore, further highlights the contrast between the living conditions of the 1830s and those of the 1870s (Beer 24-25).

This observation could again be linked to Flint’s analysis of materiality within Middlemarch and the conclusions she foregrounds in Lydagate’s sentences that the real appeal in characters, especially females characters, does not lie in the elegance of their clothing or household objects, and might be seen as “without lilies and roses” (Eliot 505), yet they possess other, more significant attributes that set them apart, something connected to the “expenditure of well-directed personal effort” (Flint 74), such as Dorothea’s “head for business most uncommon in a woman…the skillful application of labor” (Eliot 439) or Mary’s assertion that “…my family is not fond of begging…we would rather work for our money” (Eliot 224). When Rosamond indirectly conveys to Mary that her beauty is not her standout quality but rather her skill in needlework, Mary confidently responds, affirming that these talents have rendered her "sensible and useful" and asserting that her character is of the type "interesting to herself" (Eliot 116), even if superficial individuals like Rosamond may fail to recognize the depth and fulfillment derived from hard work. While superficial characters may overlook it, true "judges" (Elio 504) will always discern the intrinsic value, as we see in Lydgate when “It angered him to perceive that Rosamond’s mind was wandering over impracticable wishes instead of facing possible efforts” (Eliot 514).

Notably, the novel unfolds admiration for endeavors and values ingrained in labor, as we especially see with the characters of Dorothea and Mary. It is conceivable then that individuals in the depicted era seemingly found contentment and satisfaction in facing hardships and challenges, part of which possibly due to the absence of advancements that could have eased their lives. Not only were they seemingly oblivious to the transformative potential inherent in technological innovation like the sewing machine, content in the belief that enduring hardships bestowed greater value upon their efforts, but there also existed a latent fear that such progress might induce a certain sense of disability, particularly of a mental and spiritual nature. This apprehension stemmed from the notion that the introduction of this innovative tool might supplant their roles, thereby robbing them of the profound sense of accomplishment—and notably, in the case of women, the intrinsic connection to femininity associated with the acts of sewing and needlework, which were intricately linked to a sense of achievement derived from sustained physical effort. In a manner akin to this, we observe a parallel sentiment in the response of the Frick community to the introduction of the new railway. There exists a reluctance to embrace this addition, coupled with an overarching sense of suspicion that this development may not ultimately prove advantageous to them:

“In the absence of any precise idea as to what railways were, public opinion in Frick was against them; for the human mind in that grassy corner had not the proverbial tendency to admire the unknown, holding rather that it was likely to be against the poor man, and that suspicion was the only wise attitude with regard to it” (Eliot 441)

Extending the argument from the preceding paragraph, the other advertisement concerning the sewing machine, which is provided above, highlights its silence as a distinctive advantage, and brought to my mind a line from the article "Plasticity, Form, and the Matter of Character in Middlemarch." While the primary focus of the article revolves around the interplay and relationality between "human psychology" and its "material substrate" (Brilmyer 60), the advertisement's emphasis on silence and its portrayal as a solution to a problem, coupled with earlier discussions on the perception of sewing being primarily associated with women (particularly those of limited means) and the resistance towards perceiving themselves as deserving of advancements for an easier life, aligns conceptually and thematically with Brilmyer's illustration of folding a piece paper: “A piece of paper, once folded, folds more easily the second time; likewise, an ankle once sprained is more likely to be reinjured; joints once afflicted by rheumatism are more prone to relapse” (Brilmyer 64). This correlation can be considered in the context of the discourse on habitual ignorance. Once women become accustomed to gender-based discriminations, exemplified by being cast in the role of primary sewers, as discussed earlier, the assimilation of such biases becomes second nature. It becomes ingrained for them to navigate additional layers of consideration directed towards various matters and other individuals, all the while neglecting to contemplate the potential convenience afforded to them. An illustration of this is the inclination to regard the sounds produced by the sewing machine as a nuisance rather than acknowledging the ease it brings. Furthermore, this contemplation brings to mind the numerous instances of silence in the novel (which are more in number when involving female characters), such as when "Dorothea had learned to read the signs of her husband's mood, and she saw that the morning had become more foggy there during the last hour. She was going silently to her desk when he said, in that distant tone which implied that he was discharging a disagreeable duty" (Eliot 245) or when she "was silently occupied with what she ought to do as the owner of Lowick Manor with the patronage of the living attached to it" (Eliot 394).

The advertisements featured in the eighth book of the novel adeptly contribute to depicting the distinctive expectations and discriminations concerning women—specifically, what society perceived and expected of them versus their true desires or capabilities. In essence, the women of that era were expected to express their femininity through traits of submission, limited education, and a prescribed style of dressing, as portrayed by the novel and evident in the advertisements emphasizing beauty expectations. This is exemplified in the advertisement above of decorative accessories exclusively tailored for women, insinuating that lacking such embellishments renders them "not genuine." Consequently, these societal expectations are the forces that compel figures like Rosamond to steadfastly maintain their image as the "notorious clothes-horse" (Flint 69), resolutely upholding an appearance in which "there was not room enough for luxuries to look small in" (Eliot 546). Simultaneously, characters such as Mary and Dorothea emerge as individuals who hold a profound affinity for reading books. Notably, Mary becomes one of the characters who ultimately authors a book in the Finale, the credit of which is given to Fred (Eliot 635), seen as natural at the time when the novel is set and not as natural at the time when the eight volumes were published because of the numerous ads on authorship and women authors.

The contrast presented here lies in the nature of Middlemarch as a Victorian novel, which "describes, catalogs, quantifies, and in general showers us with things: post chaises, handkerchiefs … dresses of muslin, merino, and silk … These things often overwhelm us at least in part because we have learned to understand them as largely meaningless" (Freedgood 1). This stands in juxtaposition to the advertisements that stress the significance of the unexplored and unexamined aspects. The coexistence of these advertisements (seeming contradictory below the surface when considering the characters and their aspirations) within a single book serves to provide readers with a more profound comprehension of the harsh reality wherein women's efforts were occasionally callously overlooked during that era. An exemplification of this oversight is evident in the instance where Mary's authored work is attributed to Fred, thereby diminishing Mary's role, talent, and aspirations to those for which she was conventionally acknowledged, namely, sewing and needlework.

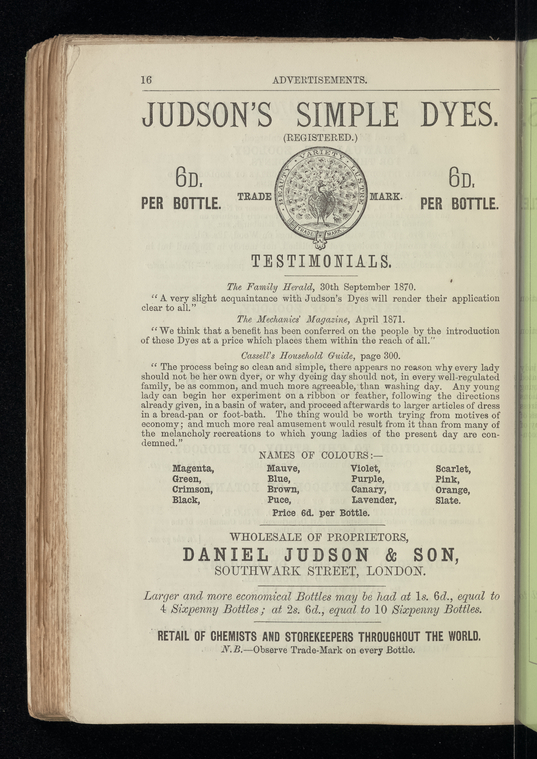

Initially elusive but discernible upon closer examination, an intriguing contrast embedded in George Eliot's portrayal of dress and landscapes in the novel finds explicit articulation in the textual representation of Judson's simple dyes advertisement. As stated by Beer, the temporal gap between the novel's narrative setting and its composition and publication reveals a notable transformation in the chromatic palette of clothing and art, attributed to the emergence of aniline dyes and chromolithography, which brought forth more vibrant and flamboyant tones. In the 1830s, the prevalent hues for perception were rooted in the ochre and earth tones reminiscent of Dutch painting and the Norwich school, such as the instances we have of “his [Naumann’s] own plain vivacious person set off by a dove-colored blouse and a maroon velvet cap” (Eliot 195) or “Rosamond in her cherry-colored dress with swansdown trimming about the throat (Eliot 377), whereas by the 1870s, the world had transitioned into a more vivid and extravagant spectacle (Beer 24).

Another noteworthy element that captured my focus in this advertisement, and subsequently resonated across a spectrum of other advertisements, pertains to the notable contrast in verbosity. Unlike many advertisements characterized by extensive textual descriptions, those related to sewing machines adopt a predominantly visual approach, presenting concise descriptions accompanied by minimal textual elaboration. These advertisements may not only inadvertently echo elements of bourgeois life without a conscious effort to synchronize with the textual narrative—meaning, the visual elements in the advertisements may convey a broad representation of a particular lifestyle or social class without establishing a connection to the specific details mentioned in the text (Beer 18-19)—but it could also be contended that the absence of a textual component in sewing machine ads, comparatively speaking, contributes to the same effect. This scarcity of text might be seen as offering evidence of what was considered noteworthy to highlight and what was anticipated of women to excel at during that era. Consequently, the intentional vacant physical space on the page serves to prevent an overwhelming barrage of words, ensuring that the intended goal and emphasis are immediately and effectively grasped by the readers of that time.

As a final point, it was interesting to me how this advertisement invites reflection on the profound reliance of Middlemarch's society on the "textile industry, specifically, the weaving of silk ribbons" (Flint 67), drawing parallels reminiscent of George Eliot's childhood in Coventry. The integration of innovative dye production techniques involving manganese (Beer 23-24) and the nuanced exploration of hand-looms versus steam-driven looms (Flint 67) emphasize the pivotal role played by workers in mines and dyeing houses in upholding both the town of Middlemarch and its economic foundation. This significance is exemplified through Mr. Bulstrode, characterized as "a sleeping partner in trading concerns, in which his ability was directed to economy in the raw material, as in the case of the dyes which rotted Mr. Vincy’s silk" (Eliot 488). Such advertisements, particularly that of Judson's Simple Dyes, not only serve to amplify the visibility of workers for initial readers but also transform the perception of dyeing work—from being perceived as hazardous and unclean factory labor to a refined and domestic pursuit.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the exploration of Middlemarch's original publication emphasizes the value of approaching familiar subjects with a fresh perspective. Eliot's notion of reconsidering old subjects without undue influence underscores the rationale for revisiting Middlemarch with a contemporary digital lens. This examination focuses on enduring themes like the textile industry, needlework, costume, and sewing within the eight volumes. Particularly intriguing is the role of original advertisements in providing insights into their impact on the novel's initial readership in 1871 as “there are some forms of knowledge that verbal representation can only hint at, such as sensory imagery, bodily movements, and affective states” (Auyoung 86). These advertisements serve as a shared space of expectation and necessity that connects the writer with the initial readership. These ads not only highlight satisfaction but also unveil a sense of yearning, drawing attention to some collective experiences among the first readers without explicit commentary as “… artworks are like picture puzzles in that what they hide … is visible and is, by being visible, hidden” (Adorno 121).

Works Cited

Adorno, Theodor W. Aesthetic Theory. London, Continuum, 2002.

Auyoung, Elaine. George Eliot’s Promise of More. Oxford University Press EBooks, 18 Oct. 2018. Accessed 27 Nov. 2023.

Beer, Gillian. “What’s Not in Middlemarch.” Middlemarch in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Karen Chase, Oxford University Press, 2006, pp. 15–35.

Brilmyer, S. Pearl. “Plasticity, Form, and the Matter of Character in Middlemarch.” Representations (Berkeley, Calif.), vol. 130, no. 1, 2015, pp. 60–83, https://doi.org/10.1525/rep.2015.130.3.60.

Eliot, George. "Notes on Form in Art” (1868). Essays of George Eliot. Ed. Thomas Pinney. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1963. pp. 431-6.

---. Middlemarch: A Study of Provincial Life, edited by Gregory Maertz, Broadview Press, 2004.

---. Miss Brook. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1871. Vol. 1 of Middlemarch: A Study of Provincial Life. 8 vols. 1871-1872. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 28 Nov. 2023.

---. Old & Young. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1871. Vol. 2 of Middlemarch: A Study of Provincial Life. 8 vols. 1871-1872. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 28 Nov. 2023.

---. Sunset and Sunrise. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1871. Vol. 8 of Middlemarch: A Study of Provincial Life. 8 vols. 1871-1872. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 28 Nov. 2023.

---. The Widow and the Wife. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1871. Vol. 6 of Middlemarch: A Study of Provincial Life. 8 vols. 1871-1872. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 28 Nov. 2023.

Flint, Kate. “The Materiality of Middlemarch.” Middlemarch in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Karen Chase, Oxford University Press, 2006, pp. 65–85.

Freedgood, Elaine. The Ideas in Things: Fugitive Meaning in the Victorian Novel. Chicago (Ill.); London, The University of Chicago Press, Cop, 2010.

Lo, Stephanie. “Who Invented the Sewing Machine? History, Facts & Scandals Revealed.” Contrado Blog, 10 Apr. 2019, www.contrado.co.uk/blog/history-of-the-sewing-machine/#:~:text=Barthelemy%20Thimonnier%2C%20a%20French%20tailor. Accessed 26 Nov. 2023.

Thierauf, Doreen. “The Hidden Abortion Plot in George Eliot’s Middlemarch.” Victorian Studies, vol. 56, no. 3, 2014, pp. 479–89, https://doi.org/10.2979/victorianstudies.56.3.479.