Paratext is the Spice of Life: Diversity of Genre in Book Advertisements and the Establishment of Realism in the First Publication of Middlemarch

Introduction

"Every limit is a beginning as well as an ending” (Eliot 635); George Eliot thus opens the “Finale” of her novel Middlemarch. At the end of the eighth and final book of Middlemarch the publisher William Blackwood & Sons’ includes an extensive catalogue of their other published titles that were available for purchase. The titles range from non-fiction history books, to atlases, to religious devotionals, and new translations of classic epics, providing insight into consumer culture and audience interests in the 1870s. Additionally, the range of genres being advertised reflects the heterogeneity of genre found in the details of Middlemarch. I argue that the inclusion of Blackwood’s catalogue at the back of the final book of Middlemarch reflects the generic mix found in the novel, specifically in conjunction with established historicity through historical and social context provided, that Eliot uses to create a sense of realism. Though I will not be discussing every genre of book being advertised at length, I have highlighted history, science, and religion as genres that inform both Eliot’s creation of realism in Middlemarch and that are also found repeatedly in the Blackwood catalogue.

Books as Part of Commodity Culture

William Blackwood & Sons’ decision to include a catalogue of titles available for purchase is reflective of the time of year that the final book of Middlemarch was released. Donald Gray explains in the chapter “George Eliot and Her Publishers” that the parts of Middlemarch were sold every other month, except for the final two parts, which came out a month apart (Gray 66). Based on the Christmas advertisements found in Book VIII, the inclusion of Blackwood’s catalogue was likely meant to encourage readers to purchase their other books as Christmas gifts for loved ones. As Tara Moore notes in the chapter “The Expansion of Christmas Consumerism: Gifts and Commodities” in her book Victorian Christmas in Print: “Reviews began to shift away from counseling what the consumer should read himself to what he should buy for others. As the new, post-1840s Christmas accelerated … [advertisements] took up more and more of the periodicals’ advertising space as books enjoyed special status as ideal Christmas gifts” (Moore 103). Though Middlemarch was not published in a periodical, we can see the high volume of advertisements for books surrounding each edition of Middlemarch. Donald Gray credits George Eliot’s partner George Henry Lewes with including advertisements alongside the publication, explaining: “Lewes profitably revived the practice of selling advertising in the bimonthly or monthly parts of [the] novel. At his suggestion Blackwood published the last two parts of Middlemarch a month rather than two months apart in order to have whole book ready for the Christmas book-buying season” (Gray 66). Moore’s and Gray’s observation of the growing volume of advertisements for books can be found in the Blackwood catalogue included at the end of Middlemarch.

Above, you will find the title page of “Catalogue of Blackwood & Sons’ Publications”. This page acts as a cover for the catalogue, even though it is found within the publication of Book VIII of Middlemarch. The blank space on the page mimics the title page of a book. You can find the title page of Book VIII of Middlemarch directly above the title page of the catalogue for comparison. Additionally, the page numbers following this catalogue’s cover begin from page 1 and increase from there. By providing a title page for the catalogue and its own set of page numbers, the publisher is setting apart this portion of the physical book from other advertisements and from the narrative text of Middlemarch. To readers at the time, these details would have likely indicated that the catalogue possessed a degree of importance and value as it was being treated like its own separate text.

The catalogue is over 50-pages long, and the range of books being advertised demonstrates the publisher’s goal to appeal to a variety of audiences, ensuring that consumers looking to buy books as gifts are guaranteed to find a title that would suit the interests of their loved ones. The diversity of titles also reflects the interests of readers in the 1870s. Eliot employs a similar method in Middlemarch to establish realism. Each of the characters have their own hobbies, interests, and business ventures that can also be found in the range of titles being advertised in the catalogue. Readers of Middlemarch would have likely found the breadth of interests and hobbies of the characters as echoing their own. Blackwood’s mission to increase sales by appealing to a variety of readers through the titles they published, reflect Eliot’s own goal of establishing realism through a diversity of characters and their individual goals and interests.

History

Over 150-years after its first publication, it is difficult to imagine that Middlemarch could have been viewed as a historical novel by first readers. However, Eliot sets the novel roughly 40-years in the past at the time of publication. As Jerome Beaty observes in his chapter “History by Indirection: The Era of Reform in Middlemarch”: “The events of Middlemarch are supposed to take place between 30 September 1829 and the end of May 1832. Most of the historical references in the novel therefore concern events and personalities involved in the struggle for political reform which culminated in the passage of the First Reform Bill in June 1832” (Beaty 173).

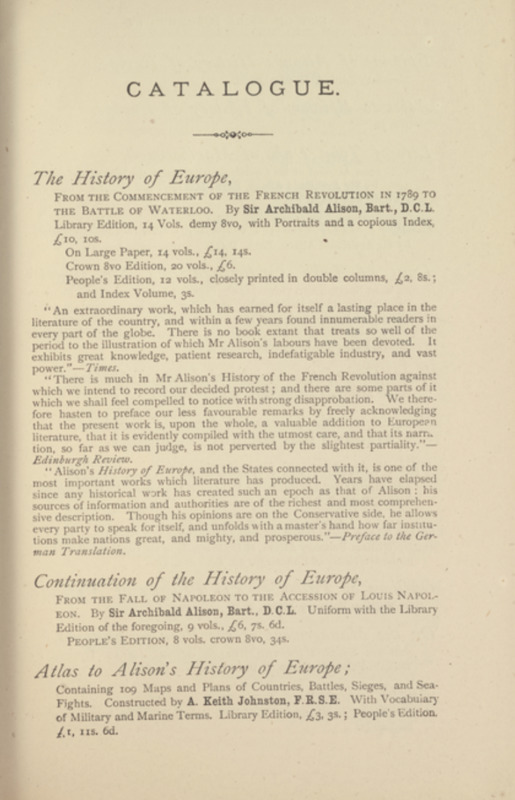

Based on the list of books being advertised in Blackwood’s catalogue, history books covering a variety of historical topics were popular with Victorian readers. In the advertisement above, you can see that the Blackwood catalogue opens with The History of Europe. If you look at the print below the title, you will find various versions of the book available for purchase, beginning with the fourteen-volume “Library Edition” that includes “Portraits and a Copious Index” (The History of Europe Advertisement 1) that cost10 and 10 shillings, which would roughly come to

935 in October 2023 (Bank of England Inflation Calculator). If a consumer wished to purchase the version printed on “Large Paper”, it would have cost them

14 and 14 shillings, or roughly

1310 in October 2023 (Bank of England Inflation Calculator). The slightly more affordable twelve-volume “People’s Edition” is listed as being “closely printed in double columns” and would cost consumers

2 and 8 shillings, or about

140 in October 2023 (Bank of England Inflation Calculator), with the index available for purchase separately for 3 shillings. When consideration is made for inflation, it becomes evident that these volumes of books were a luxurious gift. However, the variety of versions available for purchase indicate that there was a market for these books, ranging from the wealthy who could afford the “large paper” fourteen-volume Library Editions, to the decidedly more middle-class who would have likely purchased the People’s Edition.

The reviews found underneath the advertisement for The History of Europe, come from the Times, Edinburgh Review, and the preface to the German translation of the book. In all three of the featured reviews, they comment on the accomplishments of the book, with the review from Times stating: “An extraordinary work, which has earned for itself a lasting place in the literature of the country, and within a few years found innumerable readers in every part of the globe” (The History of Europe Advertisement 1). Across the catalogue, dozens of history books and books about historical figures are available to purchase from Blackwood & Sons’. However, choosing to advertise such a decadent multi-volume collection with reviews positing its cultural and historical significance, would suggest that there is a sense of pride the publisher feels in printing this book, as well as believing that there is a market for it amongst consumers.

The historicity that Eliot employs through her close attention to political and historical details, indicate that Eliot would have very likely consulted a variety of historical texts, both archival primary source and curated sources like The History of Europe. The events discussed in Middlemarch would likely have been familiar to readers at the time of publication, with many of them possibly having lived through these historical events. However, the historicity that Eliot carefully creates does not necessarily make Middlemarch solely a form of historical fiction. Rather, historical allusions are used as a means to further assert realism by locating the story within a specific time period. In his article “Middlemarch and History”, Michael York Mason describes how Eliot’s own relationship to the 1830s is one built on research rather than memory, as Eliot would have been too young to recall specific historical and political details from the period (Mason, “History” 417). Mason describes the way in which Middlemarch may be categorized as a “historical novel”, stating: “To start with, such a novel must in some way be about the past for its own sake. It must have, and Middlemarch does have, a concern for the proper representation of the past as an end in itself which is not guaranteed, though it is permitted, by research in the British Museum” (417).

The “proper presentation” of historical events that Mason refers to is also taken up by Jerome Beaty but is situated differently in the text. Mason feels that the historical details greatly inform the trajectory of characters, stating: “Historical references in a novel are not to be justified on the ground of their being unnoticeable, but rather because they are meaningful” (419). By contrast, Beaty observes in his chapter on history in Middlemarch that the historical dates, issues, and events that are subtly referenced by Eliot are not the focus of the novel’s events. They are periphery details that help propel the plot, as Beaty states: “The major political events…have effects with no surrounding air of ‘momentous occasion’; they assume their natural place in the lives and actions of the characters, yet they do not distract the reader from the fiction” (Beaty 177).

Though the two scholars may be at odds over the significance and effect of established historicity in Middlemarch, the narrator of the novel asserts that both the readers and the narrator themselves hold similar responsibilities to a historian. Early on in Book II, the narrator discusses Henry Fielding and his self-proclaimed status as a “great historian…who had the happiness to be dead a hundred and twenty years ago” (Eliot 136). The narrator is critical of Fielding’s reputation as a historian due to the privileged position he had by living in an easier, more comfortable past. The narrator views themselves as a more legitimate historian due to the responsibility they feel to telling the stories of people. The narrator says:

We belated historians must not linger after [Fielding’s] example; and if we did so, it is probable that our chat would be thin and eager, as if delivered from a campstool in a parrot house. I at least have so much to do in unravelling certain human lots, and seeing how they were woven and interwoven, that all the light I can command must be concentrated on this particular web, and not dispersed over the tempting range of relevancies called the universe. (137)

The narrator speaks to the reader in the first-person plural inviting them into the shared responsibility of “unravelling certain human lots”. By referring to themselves and the readers as “belated historians”, the definition of what qualifies as “history” in the novel is challenged. It is not just the historical facts and political allusions from the 1830s, but instead the documentation of human relationships, the “web” that the narrator refers to. The historical references to the political landscape of the 1830s is a vehicle for characterization, rather than historical exploration of facts. This supports Beaty’s point when he says: “…[Eliot] rarely addresses historical information directly to the reader, preferring to introduce it as part of the everyday affairs of the fictional characters, rarely overshadowing personal affairs, often overshadowed by them…” (Beaty 179). As Beaty argues, the key driving force for the characters and for the plot is still their own personal affairs, not the historical events or political times in which they live.

The attention to historical details and the historicity that is accomplished as a result, contribute to the realism of the novel. The resulting effect of these historical details is a type of “historical realism” that Brian Swann refers to in his article “Middlemarch: Realism and Symbolic Form”, stating: “[Eliot]…extends the meaning of historical realism, not only in the direction of the incorporation of strictly accurate historical backgrounds, but by embodying the ‘mythopoeic aspect of history’” (Swann 283). The “mythopoeic aspect of history” that Swann refers to can also be found in the narrator’s articulation of history as being more involved with the nature of human relationships than just objective historical facts. However, Eliot as the author has claimed an authority over how history is perceived in the text and how it contributes to realism, as Swann argues: “George Eliot had claimed the right to take as reality that which is selected by her consciousness. The mind is not merely a mirror, nor is reality simply objective verisimilitude” (283).

The “extension” of what qualifies as historical realism that Swann identifies, together with the authorial authority Eliot exercises, and Beaty and Mason’s observations of the effects of historical details, all work together to paint the landscape in which Middlemarch takes place. The historical elements are essential for the characters’ development, even as their personal lives take precedence over the historical events. In relation to the history books being advertised, books that pride themselves on delivering complete and objective facts, like The History of Europe, would provide a direct contrast to readers between a book of history and a historical novel. It would become apparent to readers that the historical elements of Middlemarch act as an essential accessory to the story being told, but it is not a book that will convey solely objective facts.

Science and Religion

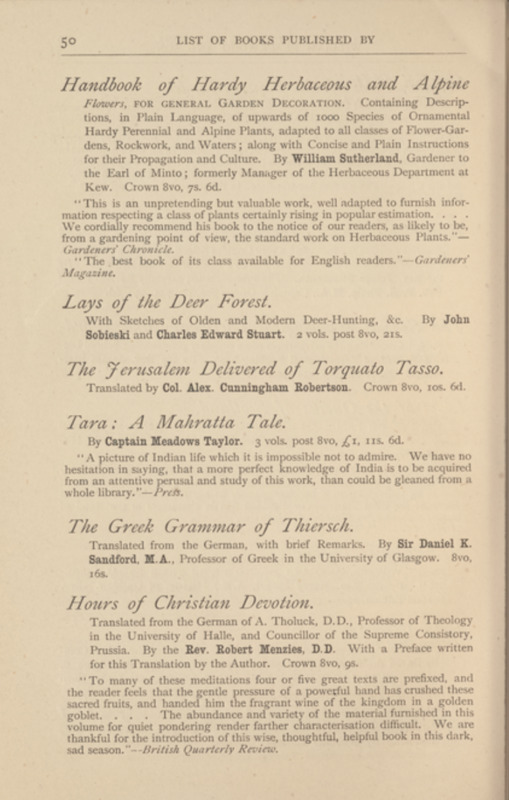

In her chapter “What’s Not in Middlemarch” Gillian Beer discusses the advertisements present in the first publications of Middlemarch, stating: “The advertisements flout the insights of the novel while provocatively demonstrating the degree to which the novel itself draws on a common material world shared, apparently un-self-consciously, by George Eliot and her first readers” (Beer 20). The “material world” that Beer is referring to goes beyond the advertisements for specific products and books and can also be applied to the ideologies that were shaping the Victorian era. Within the Blackwood catalogue, both religious and scientific texts are advertised alongside one another. They coexist within the same pages, much in the same way that religion and natural science were coming to coexist within Victorian society and interests. For example, in the advertisements above, you can see that Hours of Christian Devotion is being advertised on the same page as Handbook of Hardy Herbaceous and Alpine Flowers (Hours of Christian Devotion Advertisement 50).

It is worth noting that Blackwood’s catalogue does not categorize books by genre or type but are instead listed by author. By choosing to order the books by the authors’ last names rather than by subject, this suggests a democratic approach to the categorization of books, meaning that one genre or topic is not made to seem more significant or superior to another. Beer explains how the advertisements reflect the needs and ideals of readers in the period, stating: “[Advertisements] highlight for us those areas of awareness that were then dulled by familiarity. They can also pinpoint areas of change that we shall ordinarily miss but that were shared without comment by Eliot and her readers” (24). Beer discusses how advertisements can provide insight to the everyday changes that first-readers and Eliot herself were experiencing, that would have felt normal or even mundane at the time. In the context of advertisements within Blackwood’s catalogue, the listing of scientific texts and religious texts without any particular generic hierarchy, may have seemed “familiar” to first readers of Middlemarch.

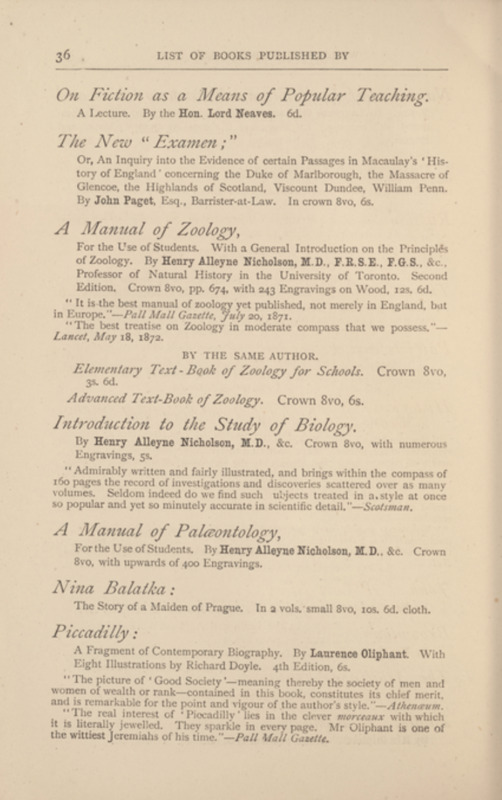

In the image that features an advertisement for Introduction to the Study of Biology, you will find a list of other scientific texts available for purchase from Blackwood, including A Manual of Zoology and A Manual of Palaeontology, though these texts are advertised primarily for use by students. However, the Introduction to the Study of Biology is commended for its accessibility and accuracy, with the review from Scotsman stating: “Seldom do we find such subject treated in a style at once so popular and yet so minutely accurate in scientific detail” (Introduction to the Study of Biology Advertisement 36). The book is being touted for use outside of academia. Though this advertisement is from 1872, Michael York Mason observes in his article “Middlemarch and Science: Problems of Life and Mind” Eliot’s commitment to establishing realism through historicity includes her attention to scientific knowledge and how it is becoming more commonplace amongst the public. Mason states: “One development in this period [Eliot] has her eye on is the growth of ‘knowledge’, which naturally includes the advance of science” (Mason, “Science” 151).

The fascination with scientific advancement in Middlemarch is perhaps most obviously found in Lydgate’s medical pursuits and his state-of-the-art medical knowledge for the period. However, it is Camden Farebrother’s hobby of collecting “pickled vermin” (Eliot 160) that reveals just how science and religion are coming to a head in the 19th – century. When Lydgate visits Farebrother’s home, he notices Farebrother’s “bookcase filled with expensive illustrated books on Natural History” (161), providing a direct link to the literary consumer culture of the era that continued into the 1870s. Even in a removed, pastoral place like Middlemarch, vicars could still access these volumes of scientific texts. Farebrother tells Lydgate about his “want of spiritual tobacco” (161) that he feels could be found if only religious texts included scientific details, stating his desires as: “…a learned treatise on the entomology of the Pentateuch, including all the insects not mentioned, but probably met with by the Israelites in the passage through the desert; with a monograph on the Ant, as treated by Solomon, showing the harmony of the Book of Proverbs with the results of modern research” (161). In this statement, Farebrother is not denouncing religion or God, and his position as vicar in Middlemarch automatically denotes religious affiliation; however, he is thinking of a hypothetical scientific study of religious events. His scientific interests do not necessarily make his beliefs and values secular, but they do impact his perception of religion, as found in his scientific treatment of it.

Farebrother’s views on knowledge in relation to science and religion is also mirrored in the advertisements for religious and scientific texts. As previously mentioned, the advertisement for Introduction to the Study of Biology highlights its accessibility as making it a desirable book to purchase. In the advertisement for Hours of Christian Devotion there is a review from British Quarterly Review that reads: “The abundance and variety of the material furnished in this volume for quiet pondering render farther characterisation difficult. We are thankful for the introduction of this wise, thoughtful, helpful book in this dark, sad season” (Hours of Christian Devotion Advertisement 50). The “quiet pondering” that the text supposedly encourages demonstrates the value placed on reflection of spiritual knowledge. The “dark, sad season” the review refers to, could partially relate to the move towards secularism across the 19th-century.

As suggested by Marilyn Orr in the chapter “Religion in a Secular World: Middlemarch and the Mysticism of the Everyday”: “George Eliot does not focus on the politics of the religious structures of the day…but continues instead to write of clerics as human beings and as citizens of the human community and of their work as part of the whole work of that community” (Orr 66). Though the British Quarterly Review may view the secularization that Eliot exemplifies in her writing as “dark and sad”, it is also a way to establish realism by humanizing characters associated with the church, and a broader reflection of society’s changing relationship with religion. Gillian Beer identifies Eliot’s secularism as essential to establishing realism, arguing that: “[Middlemarch’s] determined secularism in the portrayal of provincial life denies to 1870s readers even the imagined golden age of undisturbed belief supposedly existing in the 1830s, in the heyday of natural theology, and before the intervening tumult of enquiry that disturbed their own times” (Beer 28). Eliot seems to be using secularism to challenge the perception of readers at the time that pastoral life existed within an idealized religious period, where Christianity and religious thought was not being challenged by burgeoning scientific discoveries.

Conclusion

The combination of the detailed historicity that is established across the novel, coupled with Eliot’s exploration of religion and science coexisting in a pastoral setting, mirrors not only the generic mix of books found in Blackwood’s catalogue, but is also a reflection of society in the 1870s. By analyzing the advertisements for books available for purchase, we gain insight into the bookshelves of readers of the 1870s. When considered in the context of Middlemarch’s setting in the 1830s, we realize that the realism that Eliot accomplishes through the heterogeneity of genre in Middlemarch extends beyond the historical period in which the novel takes place, extending to a broader commentary on the societal changes occurring across the entire Victorian period.

1 All textual quotes from George Eliot’s Middlemarch are from the 2004 Broadview Press edition edited by Gregory Maertz.

2 All in-text citations for advertisements from the “Catalogue of Blackwood & Sons’s Publications” correlate to the page numbers of the catalogue found at the back of Book VIII of the first edition of Middlemarch.

Works Cited

“Bank of England Inflation Calculator.” Bank of England, 28 Nov. 2023,

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator .

Beaty, Jerome. “History by Indirection: The Era of Reform in ‘Middlemarch.’” Victorian

Studies, vol. 1, no. 2, 1957, pp. 173–79. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3825470. Accessed 29 Nov. 2023.

Beer, Gillian. “What’s Not in Middlemarch.” Middlemarch in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Karen Chase, Oxford University Press, 2006, pp. 15–35.

Eliot, George. Middlemarch: A Study of Provincial Life, edited by Gregory Maertz, Broadview Press, 2004.

---. Sunset and Sunrise. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1871. Vol. 8 of Middlemarch: A Study of Provincial Life. 8 vols. 1871-1872. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 28 Nov. 2023.

Gray, Donald. “George Eliot and Her Publishers.” The Cambridge Companion to George Eliot,

Cambridge University Press, 2019, pp. 57–75,

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108147743.005.

Mason, Michael York. “Middlemarch and History.” Nineteenth-Century Fiction, vol. 25, no. 4,

1971, pp. 417–31, https://doi.org/10.2307/2933120.

---. “Middlemarch and Science: Problems of Life and Mind.” The Review of

English Studies, vol. 22, no. 86, 1971, pp. 151–69. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/513010. Accessed 28 Nov. 2023.

Moore, Tara. “The Expansion of Christmas Consumerism: Gifts and Commodities.” Victorian

Christmas in Print, Palgrave Macmillan, 2009, pp. 99-120.

Orr, Marilyn. “Religion in a Secular World: Middlemarch and the Mysticism of the

Everyday.” George Eliot’s Religious Imagination: A Theopoetical Evolution, Northwestern University Press, 2018, pp. 59–86. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv3znz9n.8. Accessed 28 Nov. 2023.

Swann, Brian. "Middlemarch: Realism and Symbolic Form." Nineteenth-Century Literature

Criticism, edited by Russel Whitaker and Kathy D. Darrow, vol. 183, Gale, 2007. Gale Literature Criticism, link-gale-com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/apps/doc/XPUCZB886266207/LCO?u=ucalgary&sid=bookmark-LCO&xid=47a820d9. Accessed 4 Dec. 2023. Originally published in ELH, vol. 39, no. 2, June 1972, pp. 279-308.