The obsession with hair in Middlemarch - Sympathetic characters with great hair as a marketing strategy

Introduction

The first impression of a fictional character is often reliant on their outward appearance and what we assume of their character based on how we could interpret that description, be it run-down clothing, impeccably clean shoes, or, in multiple cases their hairstyle. The hair is a feature that can hint at numerous character traits, be it the character’s beauty, age, cleanliness, social standing, or familial relation to other characters. The novel Middlemarch, published in eight parts by George Eliot between 1871 and 1872, details the provincial life in the fictional Victorian town of the same name from 1829 to 1832 and features an astounding amount of hair descriptions. While this may come across as normal, even if a bit excessive, to a modern reader, the context of its publication pushes the descriptions into a different light. The advertisements across the original publications of the eight parts of Middlemarch feature many entries about hair care and restoration. In consideration, one questions whether the frequent mentioning of what the characters’ hair looks like might have been an intentional marketing move made by Eliot. The following exhibit explores the idea that the portrayal of beautiful hair on sympathetic characters in the novel increases the effectiveness of the many hair-beautifying, or -protecting remedies within the ads of the novel, further strengthened by the societal importance of hair in Victorian England. This exhibit’s definition of “sympathy” follows the depiction of Elizabeth Deeds Ermarth, who defines Eliot’s conception of sympathy as something closer to the modern concept of empathy, meaning a character is deemed as a sympathetic person if they act morally (26).

Hair as a sign of fitness and youth

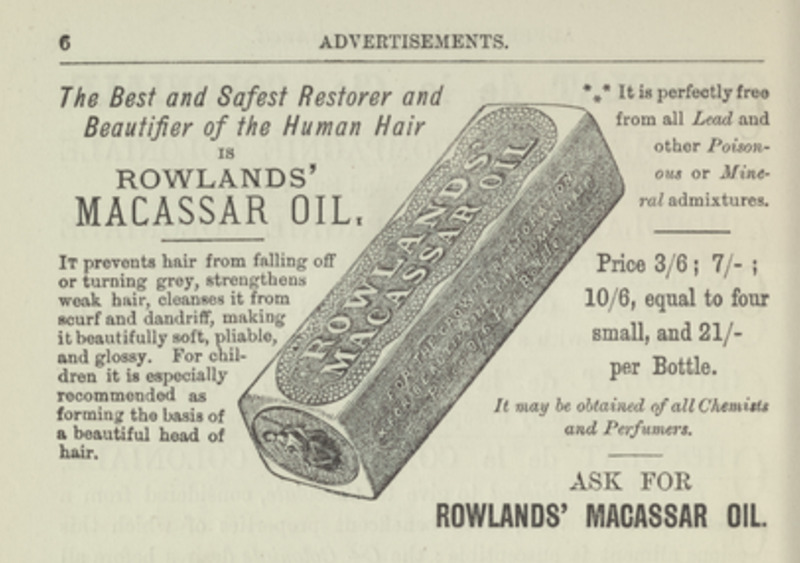

“The Best and Safest Restorer and Beautifier of Human Hair” (Eliot V.7, A6) – The Advertisement for “Rowlands’ Macassar Oil” seen above explains the mentality towards hair loss in Victorian England. People showed commitment to keep their hair beautiful, seemingly ready to risk dire consequences trying, as can be witnessed in the top right corner of the ad: “It is perfectly free from lead and other poisonous or mineral admixtures”. This statement alone implies that other hair products included these very harmful ingredients. Being old was perceived as a hindrance, not a luxury - Dependency was not desirable, in contrast to the appearance of youth. Hair loss and hair greying was a sign of the inevitably approaching death.

This inevitable death and the fear of it can be analyzed through an interaction between Fred and Mr. Featherstone. Fred offers the man his arm to help him walk on his injured leg, thinking he “should not himself like to be an old fellow with his constitution breaking up” (Eliot 115). Meanwhile, Lydgate, a young, new surgeon in town dies before the age of fifty. We learn of his death through his hair color: “Lydgate’s hair never became white” (637). He never enters the stage of being the weak old man, he keeps his image of the young surgeon with “heavy eyebrows” and “thick dark hair” (117). He can keep his youth in a sense.

Youth within the ads is glorified and in need of preservation. This can be seen within the description of the ad above, claiming the product is especially recommended for children as a “basis of a beautiful head of hair” (Eliot V.7, A6). This glorification of youth, or ageism, can be witnessed within the novel through multiple descriptions detailing the limits of older characters, their envy towards younger characters, and fear of getting old through their hair. In contrast to them, Rosamond’s hair is compared to that of children: “Only a few children in Middlemarch looked blond by the side of Rosamond” (115), this description infantilizes Rosamond, putting her in clear contrast to the thinning, greying hair of older characters, enhancing her beauty.

Dorothea and her plain dark braids

Women’s hair care in Victorian England has been analyzed a multitude of times. Kontou, Mills, and Tennant describe the importance of female hair styling during the era as an important indicator of social standing. Hair was a way to symbolize awareness of etiquette and wealth due to the rigorous rules on how hair should look during different social events and the time consumed in styling. Hair was a way to exert control as a woman, transforming it from its natural state into a controlled, decorative hairstyle (Kontou et al. 155). In Middlemarch, hair care is a natural part of the day for the female characters. Within the first part of the novel, Celia tells Dorothea of gossip she had heard from Tantripp, a servant, while her hair was getting brushed (57). This instance is interesting considering how naturally the novel establishes hair care as a daily and long task within the characters’ lives. However, it also enforces the question of whether the hair is being brought up deliberately by the author to influence the readership. One also needs to consider the probable importance of hair care to the author herself, as Eliot also lived during Victorian times, possibly including it since it was on her mind already.

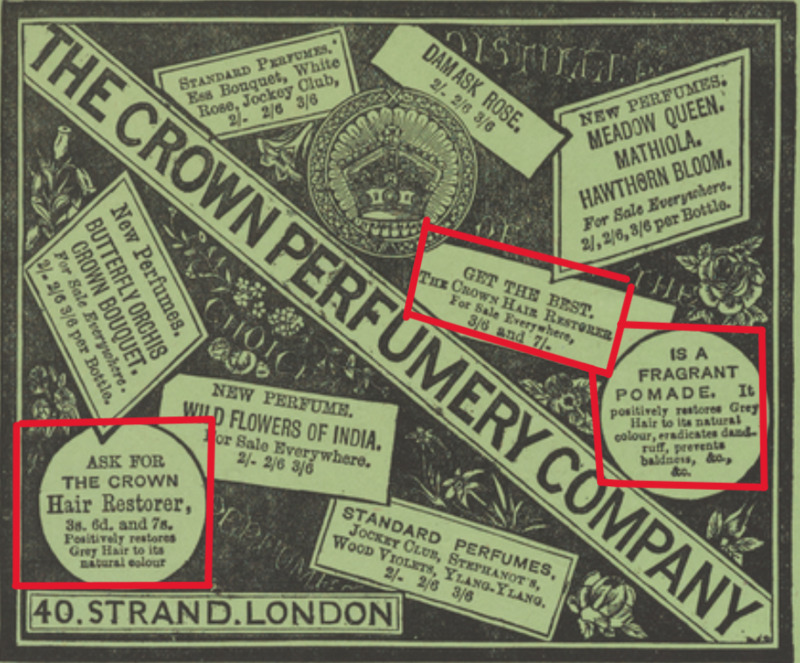

Dorothea is described as beautiful from the first page of the novel, being “that kind of beauty which seems to be thrown into relief by poor dress” (33). In addition, she is also described as sympathetic within the very first pages, as “she was open, ardent, and not in the least self-admiring” (36). However, her hair does not seem to fit the image of Victorian hair styling during her time. Eliot describes her hairstyles to be simple and natural, against societal expectations (50). Nonetheless, the descriptions of her hair are positive. “The white bever bonnet which made a sort of halo to her face around the simply braided dark-brown hair” (176) - Her hair fits her image of a sympathetic character without vanity. Furthermore, it is never unkept, but in simple styles. This image of natural hair reinforces the advertisement from “The Crown Perfumery Company” (Eliot V.6, l.g.p.), which highlights nine of its products within the ad, interestingly including three hair care products for hair restoration. Impeccably, two of the products claim to restore “natural color”. This deems natural hair color as something desirable for the readers, befitting the image of the novel’s heroin as beautiful, and possibly explaining the absence of hair dyes from the advertisements. Another important instance of Dorothea not befitting the Victorian expectations of hair styling is described after the death of her husband. On a hot day, Celia, her sister, decides to take off Dorothea’s widow’s cap. Dorothea states that she feels “rather bare and exposed when it is off”, befitting the social expectations of a widow. Sir James enters the room as “the coils and braids of dark-brown hair had been set free”, returning to their natural positions. James Chettam is very satisfied, deeming the cap a burden, constraining Dorothea (436). This burden is seemingly the power the dead husband holds over Dorothea, covering her hair, her image of youth after his death.

Ugly Casaubon – Marriage prospects and Age

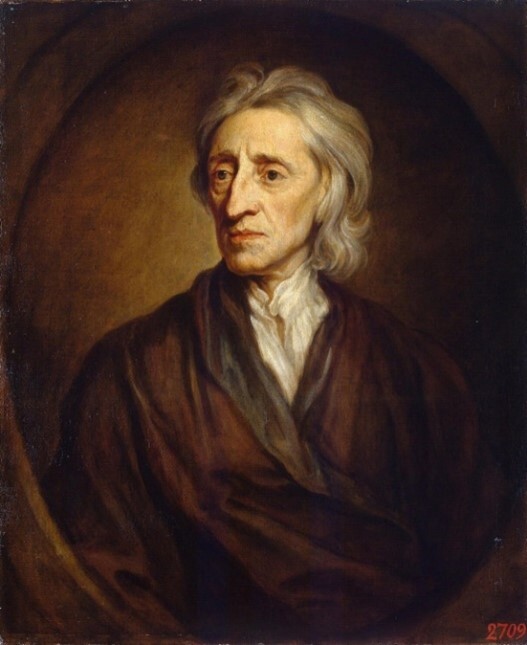

But who is the man responsible for Dorothea’s need to wear the widow’s cap? Dorothea married Reverand Edward Casaubon, a man many years her senior, shocking her acquaintances with her choice due to the possibility of marrying James Chettam, who is described as a handsome young man, his hair befitting this image: “sleekly waving blond hair” (52). Casaubon's looks, in contrast, are described to resemble the portrait of John Locke, depicted above (Kneller, n.p.). Locke, a philosopher, died in 1704, and was painted only a few years before his death, with earlier portrayals of him not befitting Dorothea’s description. The portrait is a modest depiction of an old man, without elaborate clothing. Eliot choosing Locke might have even been based on more than resemblance alone, since Locke was known to spend most of his time with his studies, making him both look and act like Casaubon (Kneller, n.p.). In comparison to Chettam Casaubon is described as “a death’s head skinned over for the occasion”(Eliot 98). While hair is an important aspect of attraction for both genders throughout the novel, Dorothea still seems to see Casaubon as a very suitable marriage partner. Celia, on the other hand, is horrified by the idea, highlighting the unattractiveness of Casaubon. Dorothea finds a resemblance in his “iron-gray hair and deep eye sockets” to Locke’s portrait (44). Celia agrees, but she perceives him as hideous, while Dorothea deems his looks becoming of a “student”. She admires him as someone she can learn from, ultimately deciding to marry him (41). This might open the question of whether his character negates the fact that his hair is perceived as “ugly” during the novel (44). Sadly, Casaubon cannot be viewed as sympathetic. According to Brilmeyer, Casaubon misjudges Dorothea. He perceives her as an “opaque” character, his ideal image of a wife, a subservient younger woman to look up to him, ignoring that her character is multi-faceted. As a result, he is disappointed when she voices her opinion or appears to slip out of his control (Brilmeyer, 73). He also views his younger relative Will Ladislaw as a love rival, showing intense jealousy towards him. The contrast between Will and Casaubon is clear as light, which is metaphorically used to describe their differences: “The first impression on seeing Will was one of sunny brightness […] When he turned his head quickly his hair seemed to shake out light” - “Mr Casaubon, on the contrary, stood rayless” (Eliot 192). This insinuates the thinning hair on Casaubon’s head, fitting the aforementioned concept of “good” hair as a sign of youth and the envy it sparks within older characters.

The ultimate exception: Rosamond

“The Ozonized Iodine baths” (Eliot V.2, l.g.p.), claiming to be the remedy for many ailments, with “no equal” product once again enforce the lengths people would go to have a full head of hair. The Hotel mentions hair restoration (along with skin softening) last in its advertisement, as the benefit supposed to persuade people to come. After all, hair is one of the many features that make one desirable - “And I like them blond, with a certain gait, and a swan neck.” (98) – This sentence is uttered in a discussion of Middlemarchers about what they deem attractive, no doubt referring to Rosamond, who is the most desirable marriage candidate in town: “Most men in Middlemarch, except her brothers, held that Miss Vincy was the best girl in the world, and some called her an angel.” (115) This image of an “angel” is further highlighted by Rosamond’s blonde hair (115). Her hair does not fit the aforementioned “natural” hairstyle but the expected hairstyle of the Victorian 1830s. Rosamond has “wondrous hair-plaits” (151). Referring back to Kontou, Mills, and Tennant and their description of the elaborate styles of the 1830s, she does seem to fit the image perfectly. However, they claim that by 1869 simpler hairstyles became the trend, focusing on “natural decorations” and moving away from extravagant hair styling (156). As a result, the contemporary reader of Middlemarch would perceive Dorothea’s hair as more fashionable than Rosamond’s. Readers, in turn, were more likely to look at Dorothea’s hair benevolently while perceiving Rosamond’s hair as “too much”. Especially, since no other female character has such elaborate hairstyle descriptions, making Rosamond stick out and seem vain, making her hairstyle not desirable to readers.

Exceptions to the rule only validate the rule

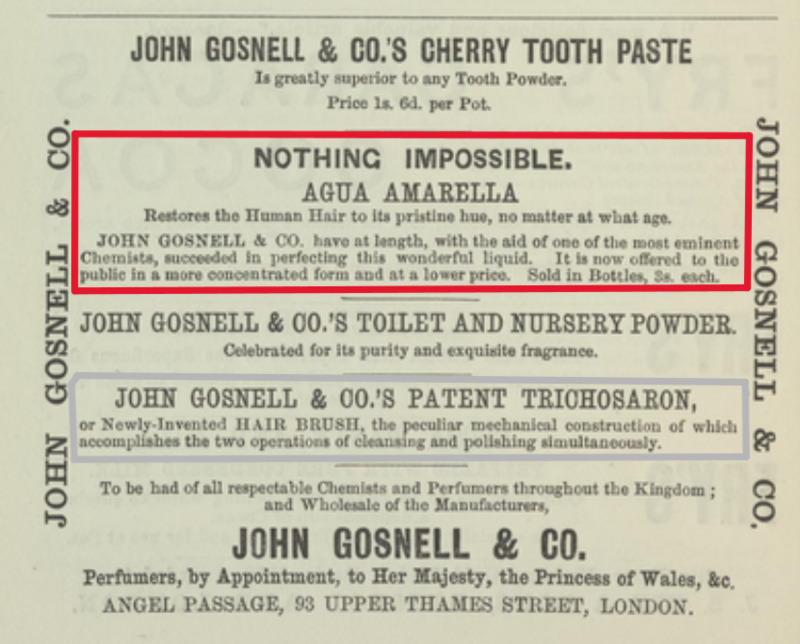

John Gosnell & Co, another Perfumer Company also advertises hair restoration through a specific type of water “no matter at what age” (Eliot V.1, A16). While this seems to be as likely as the Iodized baths getting rid of one’s baldness, they also have an advertisement for a hairbrush, which is a hairstyling tool, however it claims to be for “cleansing and polishing” instead, reiterating the contemporary trend of more natural hairstyles, away from elaborate hair styling and the manufactured curls of the 1830s. While the comparison between Dorothea and Rosamond highlights the changing trends between the time frame of the novel and its publication, the comparison between Mary Garth and Rosamond suggests deviation of two characters from the thesis of sympathetic characters having good hair.

Gallagher establishes Eliot as the nineteenth-century novelist “who is most sceptical about categorical thought”, describing the likeliness of Eliot subverting expectations of a character through their multi-faceted nature. Mary’s and Rosamond’s characters are subversions of their appearances, as shown through the interaction between Rosamond and Mary in front of their reflections. The aforementioned image of Rosamond as an “angel” is opposite to Mary being compared to “an ordinary sinner” (Eliot 115). Rosamond’s hair is described to be “hair of infantine fairness, neither flaxen or yellow” (115), with the word “infantine” further infantilizing her image. Mary’s hair is “curly dark hair” similar to Dorothea. However, her hair is “rough and stubborn” (115), natural, but clearly unmanaged, not befitting the contemporary readers’, or the beauty standard of the 1830s. A possible explanation is her social standing within Middlemarch, missing resources and time for styling. Mary looks at Rosamond’s reflection and states she is a “brown patch” next to her (116). Rosamond’s response to her is supposed to be uplifting: “No one thinks of your appearance [...] Beauty is of little consequence in reality” (116). Yet, her actions do not make her seem truthful or sympathetic. She turns her head to Mary, away from her reflection, but stops midway, appreciating the view of her neck, negating her statement through actions, showing her vanity. Following the thesis, Rosamond should have received less beautiful hair. However, that discounts the fact that Rosamond is perceived to be the perfect marriage prospect, her outward appearance is desirable to her suitors, meaning her hair could be explained by the need to make her a logical character. Mary, on the contrary, is often described as “plain” (108) within Middlemarch, despite Mary being a sympathetic character. Gallagher describes her as an example of a subversion: Her “plain” looks contrast with her “kind personality” and “sharp tongue”, showing Eliot’s non-conformity to categorization (Gallagher 65). Rosamond’s and Mary’s hair descriptions stick out due to their characters. Although, Rosamond’s hair could be considered “bad” considering her hairstyling seeming vain next to Dorothea and untrendy according to contemporary readers. Meanwhile Mary’s “bad” hair could be remedied by elevating her social class, giving her time to style it, possibly achieving a similar hairstyle to Dorothea, as she shows no signs of greying hair, or thin hair, she only lacks time for managing it.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the hair in Middlemarch teaches us a lot about its characters, often hinting at how they are supposed to be perceived. Dorothea’s missing need to follow societal standards, as well as Rosamond’s vanity can be understood through the styling of and attention to their hair. The absence of hair styling products within the ads found in the novel highlights the changing perception of hair at the time of the novel’s publication, favoring a more “natural” image. Meanwhile, the men in Middlemarch seem to be in a contest for the best head of hair in town, to attract women, youthfulness being the deciding factor. This competition, jealousy of youth and the fear of hair thinning and greying seems to be apparent not only within the happenings in Middlemarch but also in the advertisements surrounding them, which focus on dubious methods of restoring hair, even recoloring it, at any age. The theme of sympathetic Middlemarch characters receiving better hair does seem apparent throughout the novel, with Dorothea, Lydgate, Ladislaw, and Chettam fitting this image, while Casaubon, as the non-sympathetic character is dealing with jealousy of Ladislaw’s hair. Mary Garth's and Rosamond's hair are exceptions but could easily be attributed to Eliot’s focus on non-categorical thinking. Furthermore, Rosamond’s old-fashioned hairstyle from the reader’s perspective, and Mary’s missing hair care due to social standing, ultimately somewhat fit the thesis. The desirable or sympathetic characters receiving a great head of hair might have impacted contemporary readers of the novel in the perception of their own hair in comparison. Therefore, the advertisements for hair remedies likely had a more substantial impact on the readership, which is reinforced through the sheer amount of hair mentioning within the novel. The contemporary reader likely did not want their hair to look like Casaubon, or his doppelganger John Locke, but rather the plain, natural, well-managed hairstyles of Dorothea.

Citation Notes:

-> All quotes from George Eliot’s Middlemarch are from the 2004 Broadview Press edition edited by Gregory Maertz.

-> The digital editions of Middlemarch in-text will be shortened to "Eliot" + the volume of the novel (e.g. "Eliot V.4")

-> The last page (part of the green book binding) will be shortened to: l.g.p. (Last green page)

Works Cited

Brilmeyer, Pearl S. “Plasticity, Form, and the Matter of Character in Middlemarch” Representations, vol. 130, no.1, 2015, pp. 60-83.

Eliot, George. Middlemarch. Ed. Gregory Maertz. Broadview Press, 2004.

Eliot, George. Miss Brooke. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood & Sons. 1872. Vol. 1 of Middlemarch: A Study of Provincial Life. 8 vols. 1871-1872. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 28 Nov. 2023. <https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/e9ea0c80-087d-0133-420f-58d385a7bbd0>

Eliot, George. The Widow and the Wife. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood & Sons. 1872. Vol. 6 of Middlemarch: A Study of Provincial Life. 8 vols. 1871-1872. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 28 Nov. 2023. <https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/685cf040-087e-0133-7a5a-58d385a7bbd0>

Eliot, George. Two Temptations. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood & Sons. 1872. Vol. 7 of Middlemarch: A Study of Provincial Life. 8 vols. 1871-1872. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 28 Nov. 2023. <https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/887299e0-087e-0133-13f4-58d385a7bbd0>

Eliot, George. Old and Young. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood & Sons. 1872. Vol. 2 of Middlemarch: A Study of Provincial Life. 8 vols. 1871-1872. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 28 Nov. 2023. <https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/04a04fc0-087e-0133-e93b-58d385a7bbd0>

Ermarth, Elizabeth Deeds. “George Eliot’s Conception of Sympathy” Nineteenth-Century Fiction, vol.40, no.1, 1985, pp. 23-42.

Gallagher, Catherine. “George Eliot: Immanent Victorian” Representations, vol. 90, no.1, 2005, pp. 61-74.

Kneller, Sir Godfrey. Portrait of John Locke. 1697. The State Hermitage Museum, https.//www.hermitagemuseum.org/wos/portal/hermitage/digital-collection/01.+Paintings/38692/?Ing=en.

Kontou, Tatiana, et al. Victorian Material Culture. Routledge, London, 2022.