Farebrother's Cabinet: Victorians, Bugs and Longings

Introduction

In her book The Ideas in Things, Elaine Freedgood explains that her method is to take things that appear Victorian novels “literally” (36). She arms you against the limiting aspects of seeing fictional objects merely as ‘commodity culture,’ with the argument that “the world is present, and indeed ordered” in objects (36). How would the first readers of Middlemarch have found the world ordered? The advertisements that appeared in its first eight-volume edition give us a clue about those early readers ‘who easily knew things we don’t and took part in a dialogic exchange [from] which we are excluded’ (Beer 16). In this paper, I aim to add to the discussion around the paratext in the first edition of Middlemarch by examining the advertisements for popular books about natural history and science -- allowing us to eavesdrop in the dialogic exchange between the first readers and Eliot about Camden Farebrother. Farebrother is introduced to the reader as a naturalist in the same instance as we learn that he is a vicar (Eliot 125). I argue that to the novel’s first readers, Farebrother’s hobby was no mere hobby and would have been a clear signpost of the early 1830s because the figure of the cleric-naturalist was central to the decade Eliot pays tribute to in Middlemarch. I further argue, that through the books advertised in Middlemarch, we have a portal into a particular fictional object that contains more fictional objects – Farebrother’s cabinet of expensive yearnings.

Nature in the Parish

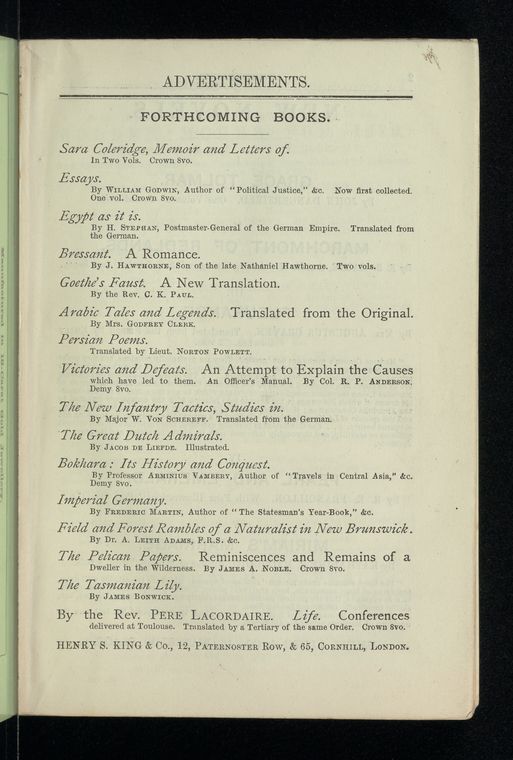

Simon Reader described the advertisements in the Middlemarch volumes ‘as barnacles on the side of this great whale’ (Reader). This is an auspicious invocation for an era in which Charles Darwin spent 8 whole years studying barnacles (Kean). However, the advertisements can tell us more about ordinary Victorians, who now ‘rest in unvisited tombs’ (Eliot 640). And it is about them that we think, as we ask what the advertisements can tell us about Camden Farebrother -- a character who is emblematic of the enormous Victorian craze for natural history (Gates 539). The Victorians wrote about nature, drew it, collected it in jars and bottles and read all that they could find. The final volume of Middlemarch advertises a book called the Field and Forest Rambles of a Naturalist in New Brunswick by A Leith Adams. Books such as these, reporting faraway locations, were popular in the Victorian era but equally popular were the books that explored nature closer home. Nature books were only marginally less popular than Dickens (Barber 14). Lynn L Merill cites Common Objects of the Country by the Reverend JG Wood, first published in 1858, as a striking example of the Victorian ‘craving for nature books’ (Merill 10). By all descriptions this was an unremarkable nature book but in a single week, it sold 100,000 copies. Clearly, this is a book that is indicative of the zeitgeist, Merill says, in comparison to other books that have been used as scholars as prisms into Victorian culture – such as Self-Help by Samuel Smiles which sold a mere 20,000 copies in its first year (10).

The authors of these nature books were often cleric-naturalists, like Farebrother. Among these cleric-naturalists, pre-eminent was Gilbert White, a vicar in Hampshire and widely regarded as the first British ecologist. White’s book Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne has remained continuously in print from the time it was first published in 1789 through the time that Middlemarch was set in, to the time it was published and to the present (Weston). However, it first became popular among the middle classes after its 1827 edition, just before the events of Middlemarch (Merill 22). Eliot’s narrator directly invokes White when talking about Farebrother (603). Victorian parishioners ‘routinely referred to their attending curates as ‘the Gilbert White of our neighbourhood’, just as Middlemarch’s narrator refers to Farebrother (R. White). Victorian naturalists were by no means exclusively men of the cloth. (Common Objects of the Country and other nature books of the era promise that they have no intimidating terminology and that they are for anyone who is interested.) Victorian naturalists cut across class, region, age and gender (Gates 541). Yet, the cleric-naturalist was a particularly well-known sub-species. Victorian botanist JC Loudon said, ‘compared even with a taste for classical studies, for drawing, for painting, or any other branch of the Fine Arts… a taste for Natural History in a clergyman has great advantages’ --- natural history being a hobby that sent the parson out of his home, into the world and the parish and in constant pursuit of appropriately difficult and hence morally uplifting tasks (Merill 42).

When Farebrother tells Lydgate that he had made ‘an exhaustive study of the entomology of this district,’ this is a very deliberate move by Eliot to take the 1870s reader to the recent past (160). White’s style of expressing wonder and devotion to nature – echoing Farebrother’s cries of ‘stupendous spider’ – through close observation set the foundation for Victorian nature writing (Gates 543). The Victorian abroad wrote extensively about natural history (Merill 54). However, the period was important for shifting its newly magnified lens to flora and fauna close to home. Richard Mabey writes that before Gilbert White, the idea of documenting the natural history of a single parish, as White did would have been seen as comical ‘idiosyncrasy’ (34).

William Paley’s Natural Theology was another book crucial to the creation of a teeming beehive of Victorian naturalists, nature writing and Anglican clerics. Paley, an Anglican priest, ‘yoked progressive optimism to his Christian vision of science’ says JFM Clark (9). Victorian England set out to collect nature and read about nature while on their way to collect it, now often a train ride away from an increasingly urbanized landscape (Clark 9). And this hectic activity was morally justified by the incredibly influential Natural Theology which was ‘posed as a scientific argument against atheism — one long line of argument showing how a scientific understanding of the natural world proves the existence and power of the one Final Cause — God the Creator’ (Thomson 220).

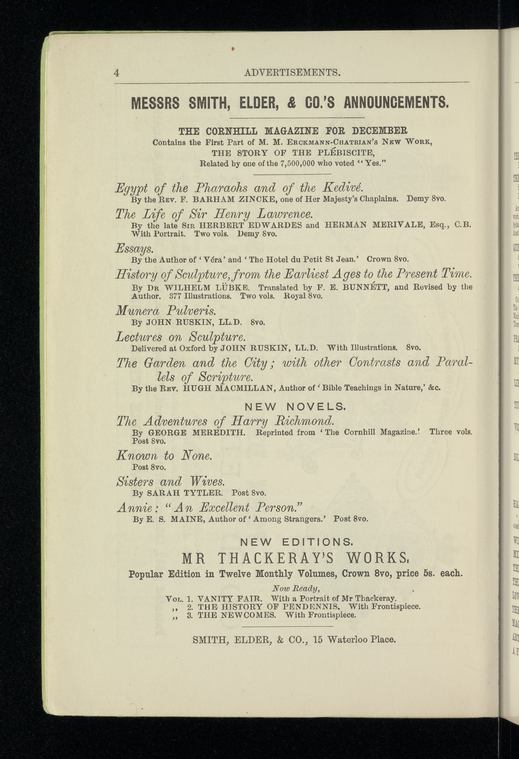

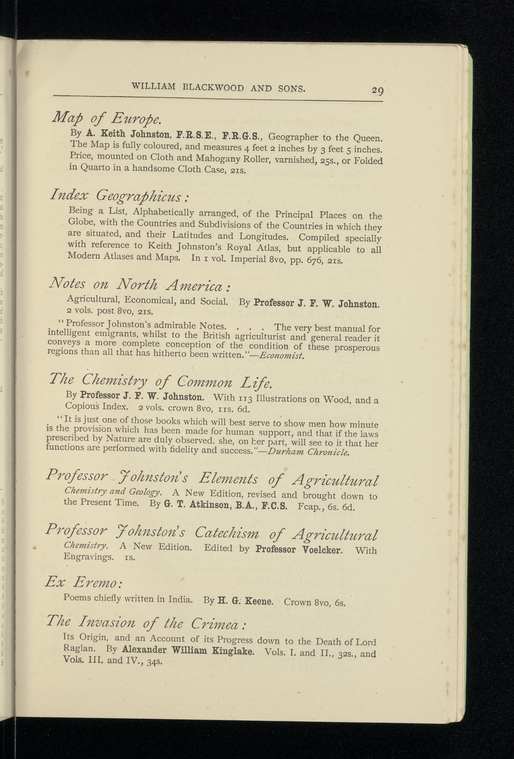

Natural theology continued to be influential through the late 19th century as is evident in the way multiple books related to natural history are advertised in Middlemarch. For instance, The Garden and The City; With Other Contrasts and Parallels of Scripture was advertised in the first volume of Middlemarch as a new book by Rev. Hugh Macmillan, the author of Bible Teachings in Nature. Bible Teachings talked about the connections between the natural and the spiritual world, sold thousands of copies in English and was translated into several European languages (Gray). In its preface, the author praises his contemporaries’ love of ‘scenery’ and exhorts the reader to remember that ‘this fair earth is a mighty parable’ (Macmillan 5). We can see this influence in another advertisement – this time for a new edition of a popular science book. The Chemistry of Common Life by JFW Johnston was first published in 1853. In 1871, it is endorsed as a book which will ‘show men how minute the provision which has been made for human support.’ The influence of Natural Theology can be seen in the blurb attributing the book’s revelations about water, soil, bread, tea and odours to ‘the Creator of all the intricate (and genuinely beautiful) apparatus of nature, down to counting the last sparrow.’

Natural theology continued to be influential through the late 19th century as is evident in the way multiple books related to natural history are advertised in Middlemarch. For instance, The Garden and The City; With Other Contrasts and Parallels of Scripture which is advertised in Vol * is recommended to the readers as a book written by Rev. Hugh Macmillan, the author of Bible Teachings in Nature. Bible Teachings in Nature was a bestseller that talked about the connections between the natural and the spiritual world, sold thousands of copies in English and was translated into several European languages (Gray). In its preface, the author praises the zeitgeist’s love of scenery and exhorts the reader to remember that this fair earth is a might parable.’ (pp v). Again, the eighth volume of Middlemarch, carries an ad for a new edition of a popular science book The Chemistry of Common Life by JFW Johnston originally published in xxx. We must make a note of how the book is advertised in 1871 — “it is one of those books which will best serve to show men how minute the provision which has been made for human support.” The influence of Natural Theology can be seen here in attributing the book’s revelations about water, soil, bread, tea, odours and bodies to ‘the Creator of all the intricate (and genuinely beautiful) apparatus of nature, down to counting the last sparrow.’

The Science of Common Life

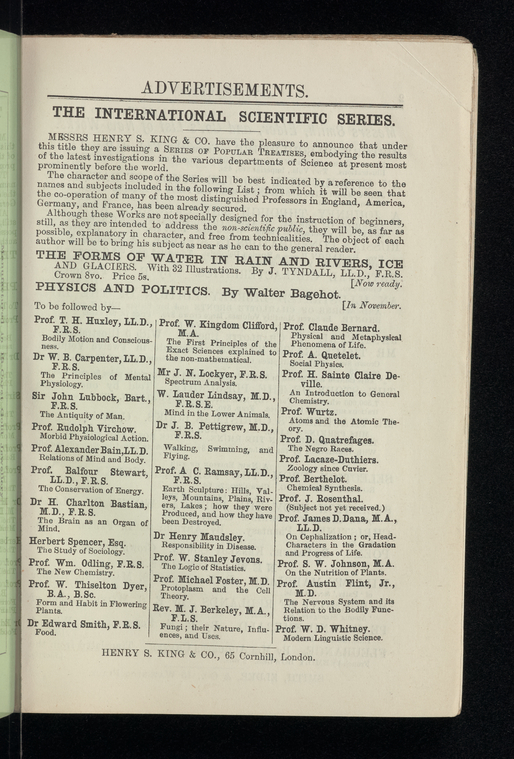

It would be a mistake to read Farebrother and Lydgate’s interests as being diametrically opposite, one an amateur naturalist and the other, a medical researcher. In the Victorian era, the veil between hobby and professional was thin (Clark 238). And the hundreds of earnest hobbyists in natural history led to the definition of the field (s) and the eventual professionalization of natural sciences in the 1870s (Gates 540). The Victorian passion for books about science and nature was fueled by science populizers and cheap publishing – two phenomena Eliot reminds readers of in the context of Farebrother. Mr. Cadwallader says that the worst he knows of Farebrother is that that he is Whiggish and supports ‘Brougham and Useful Knowledge’ (Eliot 315). In 1825, the young politician Henry Brougham had founded the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge to spread Western scientific ideas through the British empire through cheap books and magazines. By the end of 1829, the very first volume from this influential venture for popular self-education, on the "Objects, Advantages and Pleasures of Science", had sold over 31,200 copies (Secord 115). And in 1871, this is commonplace as we see an advertisement in Middlemarch for an ‘International Scientific Series’, targeting the ‘non-scientific public,’ the topics ranging from atoms to fungi to flowering plants to spectrum theory.

Tracking the publishing context of The Chemistry of Common Life (advertised in the eighth volume) too gives us clues about what Farebrother read. In 1878, Nature reviewed the latest edition of The Chemistry of Common Life. The reviewer (identified only as AG) wrote that the new edition reminded him of ‘the keen interest and pleasure’ which the book awakened in him as a boy. He goes on to say that ‘though times have changed since this book was published-now twenty-five years ago -- though we are now almost deluged with scientific manuals and primers, intended to gratify the growing taste for science, or rather, perhaps, to meet the needs of our quasi-Chinese examination systems, yet such books as Johnston's ''The Chemistry of Common Life," or the equally charming companion work," The Physiology of Common Life,'' by the late GH Lewes, have not been superseded’ (24). The GH Lewes mentioned here is Eliot’s companion, one of the great science popularizers of the 19th century and of course, Eliot too was a dedicated consumer of this emerging scientific culture as a young woman before she met Lewes (Wormald 502). This new genre is what Farebrother would have been hungry for, as he tells Lydgate about his constant longing for ‘small items about a variety of Aphis Brassicae, with the well-known signature of Philomicron, for the 'Twaddler's Magazine’ (Eliot 160). Philomicron, here is a throwaway reference to a pseudonymous writer who loves small objects such as cabbage aphids -- the kind of writer who flourished in the 1830s (Wormald 506), a reference readers who had been young in that giddy period would have remembered. James A Secord writes that from the early 1830s, ‘hundreds of thousands of men and women paid a penny a week visions of science to gain access to chemistry, astronomy, and other sciences’ (2). It is while writing for this kind of public immersed in a few decades of natural observation and scientific discovery that Eliot can place the following analogy in Ladislaw’s mouth when he talks about new art studios in a Rome crammed with antiquities – ‘small fresh vegetation with its population of insects on huge fossils’ (Eliot 224)

In the 7th volume of Middlemarch, we see an ad for an International Scientific Series of books, emphatically targeting the ‘non-scientific public,’ the topics ranging from atoms to fungi to flowering plants to statistics to spectrum theory. This love of books about science and nature was fueled by the twin phenomena of science populizers and cheap publishing, a phenomena that Eliot refers to in the context of Farebrother, who would have benefitted from it as both a cleric and naturalist. In the novel, Mr. Cadwallader says parenthetically that the worst he knows of Farebrother is that that he is Whiggish and supports ‘Brougham and Useful Knowledge’ (Eliot 315). Just six years before the time Middlemarch is set in, in 1825, the young politician Henry Brougham had founded the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge to spread Western scientific ideas through the British empire through cheap books and magazines. By the end of 1829, the very first volume from this influential venture for popular self-education, on the "objects, advantages and pleasures of science", had sold over 33,000 copies. Here is someone reflecting on those early years and what it meant to be a young reader then. This is an 1878 Nature reviewer of a newer edition of Chemistry of Common Life (the same that we saw advertised in the 1871 edition of Middlemarch). He (identified as xx) wrote that the new edition reminded of ‘the keen interest and pleasure’ which the book awakened in him as a boy. He continues ‘though times have changed since this book was published-now twenty-five years ago -though we are now almost deluged with scientific manuals and primers, intended to gratify the growing taste for science, or rather, perhaps, to meet the needs of our quasi-Chinese examination systems, yet such books as Johnston's ''Chemistry of Common Life," or the equally charming companion work," The Physiology of Common Life,'' by the late GH Lewes, have not been superseded.’ ’ This is the kind of book Farebrother would have read in his time. Note also that the GH Lewes mentioned here is Eliot’s companion, of the great science popularizers of the 19th century (Wormald 502).

It is while writing for this kind of public immersed in natural observation and scientific discovery that Eliot can place the following analogy in Ladislaw’s mouth when he talks about new art studios in a Rome crammed with antiquities – ‘small fresh vegetation with its population of insects on huge fossils’ (Eliot 224).

Stupendous Bugs

Farebrother’s particular interest in insects is also a significant way in which Eliot invokes the decade. The Victorian passion for natural history went through a series of intense fads, from shells to ferns to seaweeds (Allen). However, an interest in insects remained persistent and extraordinarily popular over the century. This makes it commonplace for Farebrother to tell Lydgate that he has ‘at least done my insects well’ (Eliot 160). Later that same evening Farebrother congratulates Lydgate for not being cut off from his true vocation — for not having to constantly yearn for the kind of things he, Farebrother, an entomology devotee wants -- ‘…a learned treatise on the entomology of the Pentateuch, including all the insects not mentioned, but probably met with by the Israelites in their passage through the desert; with a monograph on the Ant, as treated by Solomon, showing the harmony of the Book of Proverbs with the results of modern research.’ As a parson-naturalist of the period, Farebrother ‘was expected to bring philosophical and theological insight to his observations of the natural world. (Clark 28). Clark says, ‘the number, diversity and scale of insects rendered them a favourite subject of natural theologians’ (9). However, the social implications of entomological observations populated conversations across gender and class. Here is Eliot describing an occasion where a rattled Dorothea is making conversation at the vicarage. “The evening went by cheerfully till after tea, Dorothea talking more than usual and dilating with Mr. Farebrother on the possible histories of creatures that converse compendiously with their antennae, and for aught we know may hold reformed parliaments” (Eliot 603). As JFM Clark writes of the era, ‘As insects that demonstrated a human-like propensity for social organization, clever bees and ants occupied central ground in the contested terrain of nineteenth-century natural history and biology (53).

The Cabinet of Yearning

Mark Wormald says that Middlemarch ‘exploits the two most significant of the discoveries spawned by microscopy. Both were made public in 1828; both Eliot presents as they enter her provincial community’ (505). One is Karl Ernst von Baer’s discovery of the human embryo and the other is the book that Lydgate carelessly offers Farebrother, the botanist Robert Brown's Microscopical Observations. Wormald concludes that like Farebrother, Eliot too is a ‘cautious amateur microscopist’ the lenses focused on a drop of provincial life swimming with fascinating, tiny creatures (522).

I have turned my lens away from the bewitching world of microscopy and towards the other companion of the Victorian naturalist -- the cabinet. These cabinets were different from its predecessors in English homes in many ways. It didn’t just hold the whimsical purchases and acquisitions of the well-to-do. Following the trend of natural history in general, Victorian cabinets and collecting became democratic, argues Merill (108). The Victorians turn to natural history made them a particular kind of collectors, constantly in the field and the surf and the pond, in search of new experiences of ‘nature as object’ (Clark 7). And this explains part of the entreaty made in one of the new books advertised in Middlemarch, E Bruce Hanley’s Our Poor Relations. A Member of Parliament and a friend of Eliot and Lewes, Hanley argues against vivisection and cruelty against animals. He makes a special case against the ubiquitous collection of moths, arguing that it was violence done in the name of Science (Handley 58). JFM Clark has argued that, ‘insect collecting was part of a nostalgic bid to capture lost nature in an increasingly urban Victorian Britain’ (10). The Victorian cabinet was never a hodge-podge collection but always carefully arranged. ‘As such, the natural history cabinet was firmly grounded not only in the collecting urge, but also in the ingrained belief that meticulous observation was important.’ (Merill 107). Like Farebrother’s collections, the specimens were ‘ranged in fine gradation, with names subscribed in exquisite writing’ (Eliot 162). Collectors never had quite enough specimens and never had enough audiences to show – they were in a permanent state of incomplete desire to possess and to display. When they meet at the Vincy household for the first time, Farebrother demands Lydgate come see him because ‘we collectors feel an interest in every new man till he has seen all we have to show him’ (153). And later when Lydgate does visit, he urges the distracted doctor to take a closer look at each drawer. The narrator says that the Vicar laughs at himself, and yet persists in the exhibition (162).

What if we take the cabinet ‘literally’? The cabinet would have helped the first readers of Middlemarch to square Farebrother’s unsuitable hobby of playing whist with his otherwise solid character. The very first time that they are alone, Farebrother tells Lydgate that he is lucky not to know ‘what it is to want spiritual tobacco’ of natural history and science (160). What was Farebrother yearning for? He wished he was not a clergyman and could pursue natural history, the way Lydgate was pursuing medical research but he needed the income from the living to support his family and as Middlemarch makes explicit, that income doesn’t go far enough. This makes the possibility of his earning more -- first as the chaplain of the hospital and later as the vicar at Lowick Manor -- crucial turns of the plot. To Middlemarch’s first readers, the significant drain on Farebrother’s resources –given that his ‘black was very threadbare’, his study spartan and his household frugal – must have been much more evident. It certainly was readily apparent to Lydgate. The narrator says, ‘the neat fitting-up of drawers and shelves, and the bookcase filled with expensive illustrated books on Natural History, made [Lydgate] think again of the winnings at cards and their destination’ (161). As someone given to winning, whist was only paying for Farebrother’s true extravagance — natural history collection. The books were expensive already but the cabinet that would allow careful cataloguing, labelling and scrutiny needed customized building and expansion. While reading and staying in touch with the latest scientific developments was on the verge of becoming cheaper, the kind of careful and assiduous collection that Farebrother did required money. Later Lydgate tells Dorothea that Farebrother is ‘very fond of Natural History and various scientific matters, and he is hampered in reconciling these tastes with his position’ (400). Further, when Farebrother gets the living at Lowick, one of the indicators of the loosened purse-strings in the newly jubilant household is the ‘fine new study’ and the new ‘fittings’ that Fred Vincy is called upon to admire when he visits, along with the specialist ‘shallow cabinet drawers’ the labels of which Mary Garth copied in the ‘minute handwriting which she was skilled in’ (457-58).

The cabinet is also a ready metaphor of Farebrother’s yearning for his thwarted vocation, as a display of ‘longing’ (Stewart 153). We see the only instance of Farebrother being less than sanguine and genial when he finds his protocols as a naturalist is offended. On one occasion he arrives in Lydgate’s room with ‘some pond-products.’ Farebrother has a microscope of his own, as did many naturalists of the time. He comes to Lydgate’s room to borrow his superior microscope (Wormald xx). When he finds Lydgate’s specimens and apparatus are in disarray, he is annoyed enough to be sarcastic about Lydgate’s love life not being conducive to his scientific temper. He says, "Eros has degenerated; he began by introducing order and harmony, and now he brings back chaos." Not even when he reprimands Fred Vincy to whom he has lost Mary Garth does he speak as sharply. Farebrother’s true longings lie inside his cabinet, the carefully arranged, little kingdom of the naturalist (Merill 115).

Conclusion

Catherine Gallagher wrote that ‘George Eliot is the greatest English realist because she not only makes us curious about the quotidian, not only convinces us that knowing its particularity is our ultimate ethical duty, but also, and supremely, makes us want it’ (74). Lynn Merill has argued that the the famous Victorian attention to detail in art can be traced directly to the practices learnt in natural history. I would argue that in Camden Farebrother we see Eliot favour the pursuit of knowledge as a process of enthusiastic elaboration rather than the search for definitive origins (unlike Lydgate or Casaubon, the other two intellectuals of the book) – practices of the pre-Darwin naturalists. The same era which led natural history authors to bring their impeccable attention to their parishes, brought about the form of Eliot’s study of provincial life. Our distance from its original publishing context might blur the distance between the quotidian and the particular, so we don’t immediately realise that Farebrother is a specimen of a significant Victorian species.

Works Cited

Allen, David. “Tastes and Crazes.” Ed. N Jardine, JA Secord and EC Spary, Cultures of Natural History, Cambridge University Press, 1996, pp. 394-407

AG. “The Chemistry of Common Life.” Nature. Vol. 10. no. 497, 8 May 1879, pp. 25-26. PDF download.

Barber, Lynn. The Heyday of Natural History: 1820-1870. Doubleday, 1984. pp 13-14.

Beer, Gillian. “What’s not in Middlemarch.” Middlemarch in the Twenty-First Century, Oxford University Press, 2006, pp. 2-35.

Clark, JFM. Bugs and the Victorians. Yale University Press, 2009.

Gates, Barbara T. “Introduction: Why Victorian Natural History?” Victorian Literature and Culture, vol. 35, no. 2, 2007, pp. 539–49. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40347173. Accessed 2 Nov. 2023

Eliot, George. Middlemarch. Broadview, 2004.

Flint, Kate. “The Materiality of Middlemarch.” Middlemarch in the Twenty-First Century, Oxford University Press, 2006, pp. 65-86.

Freedgood, Elaine. “Introduction: Reading Things.” The Ideas in Things: Fugitive Meaning in the Victorian Novel, The University of Chicago Press, 2006, pp. 1-29

Gallagher, Catherine. “George Eliot: Immanent Victorian.” Representations, vol. 90, no. 1, 2005, pp. 61–74. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.1525/rep.2005.90.1.61. Accessed 3 Dec. 2023.

Gray, William Forbes. "Macmillan, Hugh". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography (2nd supplement). Vol. 2. Smith, Elder & Co. https://archive.org/stream/dli.ernet.1707/1707-The%20Dictionary%20Of%20National%20Biography_djvu.txt. Accessed December 1 2023

Handley, Graham, “The Two Georges and the Gunner,” George Eliot Scholars, edited by Beverley Park Rilett, www.georgeeliotscholars.org/items/show/162. Accessed December 3, 2023.

Kean, Sam. “Darwin’s Barnacles.” Distillations magazine. Science History Institute Museum & Library. 6 October 2021. https://www.sciencehistory.org/stories/magazine/darwins-barnacles/. Accessed 22 November 2023.

Mabey, Richard. Gilbert White: A Biography of the Author of The Natural History of Selborne. Profile Books, 1986.

Macmillan, Hugh. Bible Teachings in Nature. Macmillan & Co. 1871

Merill, Lynn N. The Romance of Victorian Natural History. Oxford University Press, 1989.

Reader, Simon. Interview by Charles Cuykendall Carter. Romantic Interests: Digital Middlemarch in Parts, 22 June, 2016, www.nypl.org/blog/2016/06/22/romantic-interests-middlemarch. Accessed 30 November 2023.

Samuel J. M. M. Alberti. “Placing Nature: Natural History Collections and Their Owners in Nineteenth-Century Provincial England.” The British Journal for the History of Science, vol. 35, no. 3, 2002, pp. 291–311. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4028125. Accessed 21 Nov. 2023.

Secord, James A. Visions of Science: Books and Readers at the Dawn of the Victorian Age. University of Chicago Press, 2014.

Thomson, Keith Stewart. “Marginalia: Natural Theology.” American Scientist, vol. 85, no. 3, 1997, pp. 219–21. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27856772. Accessed 21 Nov. 2023.

Weston, Phoebe. “Rude magnificence’ restored: following in the footsteps of pioneering naturalist Gilbert White.” The Guardian, 27 Jul 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/jul/27/gilbert-white-pioneering-naturalist-rude-magnificence-restored-aoe. Accessed 21 Nov. 2023.

White, Rosalind. Part Five: Provincial Piety & the Parson Naturalist’ Finding Middlemarch, Royal Holloway, University of London. Retrieved from Exploring Eliot [https://exploringeliot.org/discover-george-eliot/finding-middlemarch/parson/]. Accessed 20 Nov. 2023.

Wormald, Mark. “Microscopy and Semiotic in Middlemarch.” Nineteenth-Century Literature, vol. 50, no. 4, 1996, pp. 501–24. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2933926. Accessed 21 Nov. 2023.

Stewart, Susan. On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Duke University Press, 1993. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1220n8g. Accessed 1 Dec. 2023.

Bibliography

Carl H. Pforzheimer Collection of Shelley and His Circle, The New York Public Library. Middlemarch. Retrieved from The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1871. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/50604d10-087e-0133-5a70-58d385a7bbd0