Alluring Mistresses, Jewellery and the Dynamics of Female Inheritance and Gift in George Eliot’s Middlemarch

Onyeka Odoh

UCID: 30111417

Department of English

ENGL 609 (Middlemarch)

Professor Karen Bourrier

Alluring Mistresses, Jewellery and the Dynamics of Female Inheritance and Gift in George Eliot’s Middlemarch

[Mr Farebrother’s] pride in him [Fred], and apparent fondness for him, serving in the stead of more exemplary conduct–just as when a youthful nobleman steals jewellery we call the act kleptomania, speak of it with a philosophical smile, and never think of his being sent to the house of correction. (Eliot 207)

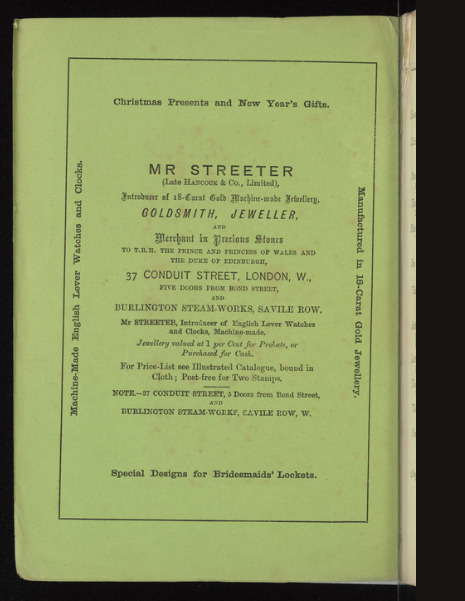

In the excerpt above, George Eliot presents the Vincys’ indulgence of Fred, despite his irresponsibility, as resulting from their premonition that he is Mr Farebrother’s prospective heir; but of stronger import is the narrator’s analogy of likening this demeanour to the lenient treatment of the theft of jewellery if the culprit is a rich person. This could suggest how George Eliot has possibly employed jewellery in this work to critique the social values of the English Victorian Period where “ideas [] inhere in things” (Freegood 112). Encountering the original green paper-back serial eight editions of Eliot’s Middlemarch (1871 and 1872) immediately convinces the reader, as Kate Flint argues, that the nineteenth-century Victorian England, mock-represented in the novel, is a “material world” (65). In line with Flint’s observations, the “materiality” of this age is underscored by the plethora of advertisements of different household commodities sandwiched at the beginning and the end of each volume of the original copies of the novel targeted at “those at once anxious about their bodies and interested in adorning them” (Flint 66). Unlike Flint who is captivated by the “textile industry” in the work, my research aims to explore Eliot’s presentation of jewellery as a symbol of female inheritance (in the case of the Brooke sisters) and gift (in the case of Rosamond) to show how women are treated as ornaments, which I consider to be possibly Eliot’s subtle way of debunking the undervaluation of Victorian English women in general. My attention is drawn to this presentation and role of ornaments in this novel from the impression created by Mr Streeter’s Goldsmith Jeweller’s advertisement on the each of the eight books of the original copies of the novel – the advert which, as Gillan Beer opines, is an “absence” in the novel but an absence that is always closely related to the themes of the work (16).

JEWELLERY AS INHERITANCE IN MIDDLEMARCH: THE BROOKE SISTERS

This advertisement calls attention to itself because, first, it appears on the entire eight volumes of the original edition of Middlemarch; secondly, it is also strategically positioned on the verso, at the very first page after the cover page of each of the eight editions of the original version of Middlemarch. The advert is addressed to “TRH the Prince and Princess of Wales and the Duke of Edinburgh” but its target audience seems to be females as discernible from the advert’s concluding line: “Special Designs for Bridesmaid’s Lockets”. This advert does more than announce the jewels (“Machine-Made English Lever watches and clocks”); it influences a new reading and understanding of events in the novel, possibly persuading the readers to consider the novel and/or jewellery from a new perspective – this case, gauging us to consider the Victorian English attitude that treats women as ornaments, yet meretricious figures meant for admiration in the drawing room. My essay sees this attempt by Eliot to enunciate the ornamentation of women as her solidarity with the nineteenth-century “campaign for improvement in women’s rights and/or deliberation over the role and status of women” (Hadjiafxendi 137). This thought pattern is opposed to earlier critics of Eliot like Kyriaki Hadjiafxendi who believe that Eliot is silent or reluctant “to engage directly with the vexed debates over the economic, political and legal status of women” (137). This critic further observes that Eliot instead presents “controversial” female characters to widen women’s sphere, after her own fashion; she concludes that Eliot is uncertain about the aims of nineteenth-century feminism (Hadjiafxendi 137). Similarly, this position is partly supported by Felicia Bonaparte in her introduction to the Oxford World’s Classics edition of Middlemarch where she maintains that “characters like Maggie Tulliver, the heroine of The Mill on the Floss…, and Dorothea Brooke in Middlemarch” are Eliot’s fictional alter egos (12). However, by reading how the advertisement enunciates Eliot’s use of jewellery as a symbol of female inheritance/gift meant to enhance the ornamentation of women, my work pushes back against such reading of Eliot as indifferent to the Victorian women’s question.

Eliot presents the character of Dorothea as challenging the domesticity of nineteenth-century middle-class British women whose banal signature in this novel manifest in their inheritance and/or receipt of the gift of jewellery. This ornamental inheritance is sharply contrasted with male inheritance that brings income and appreciates over time while that of the women only make them “alluring mistresses” (Wollstonecraft) for the male gaze. In the novel, while the closest oldest male to a deceased wealthy patriarch inherits estates, lands and other money-yielding property, a female heirloom in a similar situation inherits jewellery. Where the prospect of inheriting more than jewellery is the case, it comes with stringent conditions enlisted in the deceased’s codicil that otherwise applies differently if a male were to be the beneficiary. This is the case with Dorothea and Celia (Eliot 34) who both inherit their late mother’s box of jewellery while their buffoon of an uncle, Arthur Brooke takes charge of the estate, Tipton Grange. If at all Dorothea’s heir will inherit her late parents’ estate, then it must be on the condition that she is married and has a son; and for her to inherit her late husband, Casaubon’s estate in Lowick Gate, she has to remain unmarried, better still never marry Will Ladislaw (Eliot 391). In both cases, Dorothea’s prospects of inheritance are bound by marriage: either getting married or not re-marrying. This is not the case with male heirs like Arthur Brooke and Joshua Riggs respectively. Although we see a complication of this situation in the character of Mrs Dunkirk who manages to inherit her late husband’s wealth, yet gets conned of the wealth by Nicholas Bulstrode in a phoney marriage arrangement.

Jewellery becomes the only property, at least Dorothea describes the “purple amethyst” as Celia’s property (Eliot 38), or a gift that the female characters have and control unconditionally. Such ornamentation is, by the way, the primary objective of the education of women of the English Romantic through the Victorian era according to Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Women. In Middlemarch, Mrs Lemon’s school which Rosamond and Mary attended shows that the education of women in this era is only for ornamentation as they are not taught what will predispose them to make an impact in society but what will make them appear beautiful and marriageable. The narrator, while commenting on Rosamond’s allure and training holds that “she was admitted to be the flower of Mrs Lemon’s school, …where the teaching included all that was demanded in the accomplished female–even to extras, such as the getting in and out of a carriage” (Eliot 103).

The jewellery, therefore serves as the last paraphernalia in an “accomplished female” which objectifies women, leaving them “intoxicated by the adoration which men… pay them” (Wollstonecraft 103). Celia, more than anyone else acts out this intoxication in the intensity of the attention she pays to their late mother’s jewellery box in the text. Since the death of the Brooke sister’s parents, Arthur has had this jewellery box in his possession and forgot about it until six months before the sharing scene when he gave it to Dorothea. The narrator is not clear as to how long the box had been in Arthur’s custody but just six months after it was handed over to Dorothea, Celia is already obsessed with the sharing of the jewels as though she had been calculating to allow the ideal justifiable time to elapse for the jewellery to be shared – a disposition for which Dorothea calls her “little almanac” (Eliot 37). Celia challenges Dorothea’s claim to modesty by pointing out that “Madam Poinçon” who is stricter than Dorothea wears it; that Christians wear it too – and it’s possible that women in heaven also wear jewellery. By this, Celia shows Dorothea that keeping away their mother’s box of jewels is one way not to honour her memory. As Bonnie Zimmerman has said, this scene points to the assumed vanity of women in nineteenth-century Victorian England whose ultimate ambition ends in the drawing room in line with the advert’s “Bridesmaid’s Lockets.” This jewellery sharing scene has provoked many debates in the study of the novel. For instance, Zimmerman, based on the said scene, sees jewellery in the novel as Eliot’s symbol of female role (212); just as Jean Arnold sees jewellery in the novel as an “interactive sign” that shows the Victorian aesthetics and political economy which collaborate to shape the definition of gender (265). For Elaine Freegood, Dorothea’s ambivalence with the jewels portrays the challenges in forming connections with things if the value of those commodities is not regulated by an “impersonal form of value” (126). While I agree that jewellery, in this scene, implicates the above perspective(s), reading Mr Streeter’s advert offers a fresh perspective on how jewellery functions as a symbol of female inheritance and gift which overall presents the ornamentation of women that exposes the place of women as second to men in Middlemarch.

The above scene is meta-critical: it foregrounds how women are objectified by society through their association with jewellery; secondly it shows how women themselves corroborate this denigrating process; and lastly the absence of redeeming dimension in women themselves to change the situation. The helplessness of women in the face of this ornamentation is embodied by Dorothea whose mind, the narrator describes as “theoretic” and yearning “after some lofty conception of the world which might frankly include the parish of Tipton” (Eliot 34). This eccentric image of Dorothea is expressed in her earlier indifference towards their late mother’s jewellery which is seemingly in line with her Puritan asceticism which she has consistently displayed up until that point where she fetishisizes the jewellery, refusing to have any on the premise that it may dishonour the memory of their late mother and because of her faith that forbids her from wearing a cross as a trinket (Eliot 38). I would have considered it a complete subversion of the Victorian social female gender role had Dorothea remained consistent in this “higher purpose” disposition but like “sands in the desert, she sifts when she seems most stable” (Langer) on that role. Dorothea succumbs and accepts the Emerald ring and bracelet which are the most beautiful of the jewels; this shift in her disposition, I feel, could pass as Eliot’s way of condemning women’s culpability in their social objectification process. Her inconsistent behaviour at this point could presuppose that women’s emancipatory initiatives of the period were “dead-on-arrival” schemes. Immediately after taking the emerald jewellery set, Dorothea witnesses an epiphany which makes her empathize with the workers, the “miserable men [who] find such [precious stones], and work at them, and sell them!’” (Eliot 39). Dorothea’s conflict of interest in taking or leaving her inherited jewels foreshadows a her future similar conflict of interest about her future inheritance in Lowick Gate as to go down the social ladder and marry Ladislaw or remain in her station as Mrs Casaubon of Lowick.

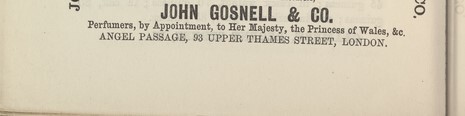

Though the situation of women is so dire that the Middlemarch society pathologizes any woman who rebels against it (Eliot 35), the same society disguises this grim situation in a cultural logic that treats women as ornaments. This interpretation can be sustained if we look at the way that other commodities, besides jewellery in the advertisements on the original edition of Middlemarch are gendered. Most others commodities that promote beauty and attractiveness are addressed to the female gender, even when such commodities are both gender-neutral or unisex. For instance, John Gosnell & Co’s advert on perfume above is addressed to “Her Majesty, the Princess of Wales” when perfume is worn by males and females. Though the idea, as it would appear to the 1870s audience, is that Her Majesty has endorsed the perfume or even bought and probably is using the perfume, but the endorsement, patronage or use of a perfume need not be gendered for the product to sell. A similar situation is happening with the advertisements on Imperial Black Silk in book two of the original edition of Middlemarch included below. The advert says that if anyone wants to read more on “scientific opinion on these materials, one should consult certain stated editions of the following magazines: Queen, Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, and The Princess of Wales. These three are all female magazines.

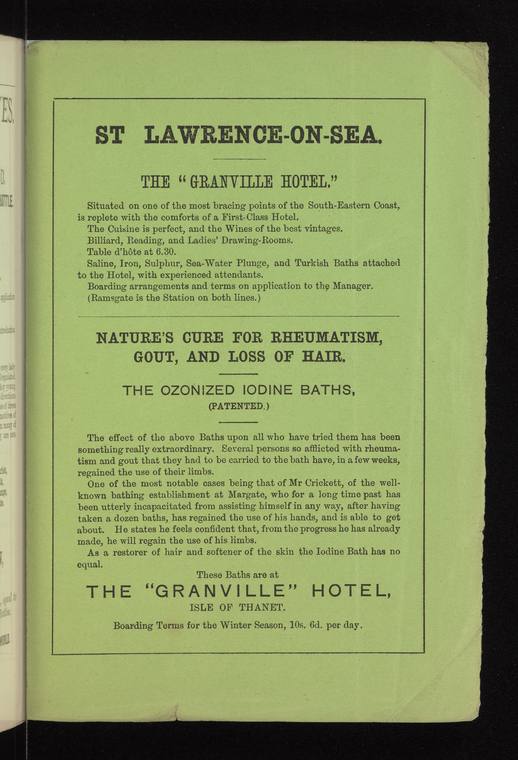

With the gender component of these advertisements, a pattern of female metonymic relationship is emerging in the adverts’ association of femininity with jewellery, perfume, silk and most importantly hotel inserted bellow. The advert announces an exquisite First Class hotel, “St Lawrence-on-Sea”, specifically, “the Granville Hotel” in the South East coast of England. The ad also outlines many attractive things that potential lodgers can look out to, including the best “cuisine, wines, Billiards, reading, and Ladies drawing room.” I was curious to know why “ladies drawing room” should be paired with these other side attractions. The answer could be that it is the spirit of the age. And when men are introduced, on the same advert page just below the hotel advert, it is now promoting “Nature’s cure for rheumatism, gout, and loss of hair” using “Ozonized Iodine Bath” – a service that is offered at the hotel above. There again, is there anything gender about rheumatism or loss of hair? I do not think so but St Lawrence-on-Sea cites an example of one Mr Crickett who was chronically incapacitated by rheumatism was carried to the bath and he is restored and he regains the use of his hands and his legs soon. The change from the dominant female to the male gender in a product that serve both men and women shows that gender and female ornamentation in this advertisements are operating at an ideological level which complicates our reading of Middlemarch.

JEWELLERY AS GIFT: ROSAMOND AND MISS NOBLE

Eliot could be using jewellery to show how the life of the Victorian middle-class lady is circumscribed by material things: inherited jewellery for the Brooke sisters; and furniture, china and gifted jewellery for Rosamond. When jewellery is not inherited, it is presented as a Marriage, Christmas, New Year or Birthday gift as advertised in Mr Jeweller’s advertisement in the original publication of Books 1 and 2 of Middlemarch which were published in November and December 1871 to be read and sometimes given as gifts. In the novel, Rosamond, more than Dorothea embodies this second phase of female ornamentation according to the narrator:

Herodotus… thought it well to take a woman’s lot for his starting-point; though Io, as a maiden apparently beguiled by attractive merchandise, was the reverse of Miss Brooke, and in this respect perhaps bore more resemblance to Rosamond Vincy, who had excellent taste in costume, with that nymph-like figure and pure blondness which give the largest range to choice in the flow and colour of drapery. (Eliot 103)

Lydgate, just like Mrs Lemon who places Rosamond’s beauty and polish above those of Shakespeare’s Juliet and Imogen, focalizes Rosamond’s ornamentation by buying her a purple amethyst necklace worth thirty pounds despite his sinking finances at the time.

However, this gift reinforces the subjectivity of the male giver and perpetuates the “ornamentation and objectification of the female recipient. To this end, Lydgate requests the jewellery back when he goes bankrupt and needs to raise money to pay off his debt (Eliot 467). Although Lydgte does not eventually take the jewellery from Rosamond as he earlier proposed, his listing it alongside his furniture and china designated to be given up for financial security shows Rosamond’s lack of agency even in “property” considered to be hers. From that moment she submits the purple amethyst, her radiance begins to diminish with Lydgate’s staggering debt and his subsequent shame and disgrace in his ignoble involvement in Bulstrode’s ploy and murder of Mr Raffles which Rosamond shares in.

The association of jewellery with Rosamond’s loss of her radiance and respect in Middlemarch is also replicated in the character of Mrs Harriet Bulstrode who, after learning of her husband’s scandal from her brother, “had begun a new life in which she embraced humiliation. She took off all her ornaments and put on a plain black gown” (Eliot 580). The act of removing her jewellery is symbolic of her shedding off her pride and dignity as well as her “rich” inheritance and her wearing a plain bonnet cap inaugurates her new life of humility consummated by their final exile from Middlemarch (Eliot 580). The association of jewellery with debasement is finally depicted in the novel, from Dorothea’s perspective, when Miss Noble parades the “tortoise-shell lozenge-box” which Will Ladislaw gifted her. This gift infuriates the heartbroken Dorothea and she leaves in anger as the gifted jewellery reminds her of the once charming prince, Ladislaw was to her before she encountered him in a compromising position with Rosamond (Eliot 603).

In conclusion, this essay looked at Eliot’s presentation of jewellery as a symbol of female inheritance (for the Brooke sisters), and as a gift (for Rosamond and Miss Noble) in a way that transforms the women into ornamental figures. This, the essay saw as possibly Eliot’s commentary on the debasement of women in Victorian England. But this renewed interest in the presentation and role of jewellery was provoked by my encounter with Mr Streeter’s Jeweller’s advertisement and similar advertisements in the original 1871 edition of the novel, which remind the readers that the life of the female characters in the novel is mediated by things. This advert on jewellery informed a different way of reading and thinking about Middlemarch in its original publication's historical context in the 1870s.

Works Cited

Arnold, Jean. “Cameo Appearances: The Discourse of Jewelry in ‘Middlemarch.’” Victorian Literature and Culture, vol. 30, no. 1, 2002, pp. 265–88. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25058585. Accessed 19 Nov. 2023.

Beer, Gillan. “What Is Not in Middlemarch.” Middlemarch in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Karen Chase, Oxford University Press, 2016, pp.15-35.

Bonaparte, Felicia. “Introduction.” Middlemarch: A Study of Provincial Life by George Eliot, Oxford World’s Classic, Oxford University Press, 1998.

Eliot, George. Middlemarch: A Study of Provincial Life, edited by Gregory Maertz, Broadview Press, 2018.

Flint, Kate. “The Materiality of Middlemarch.” Middlemarch in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Karen Chase, Oxford University Press, 2016, pp. 65-86.

Freedgood, Elaine. “Towards a History of Literary Underdetermination: Standardizing Things in Middlemarch.” The Ideas in Things: Fugitive Meaning in the Victorian Novel, University of Chicago Press, 2006, pp. 111-138.

Hadjiafxendi, Kyriaki. “Gender and the Woman Question,” George Eliot in Context,

Margaret Harris, editor, Cambridge University Press, 2013, pp. 137-144. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139019491

Wollstonecraft, Mary. “From A Vindication of the Rights of Women,” The Broadview Anthology of English Literature Volume 4: The Age of Romanticism, Second Edition, edited by Joseph Black et. al, Broadview Press, 2010. pp. 102-117.

Zimmerman, Bonnie. “‘Radiant as a Diamond’: George Eliot, Jewelry and the Female Role.” Criticism, vol. 19, no. 3, 1977, pp. 212–22. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23103202 . Accessed 19 Nov. 2023.