Part 6 - Najeeba Huda

Introduction

Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone, is rather a unique novel in the Victorian Era taking elements from the genres of Romance, Fantasy and Detective Fiction. Chapter Eleven is where the plot is driven forward through the theft of The Moonstone from Rachel’s Indian Cabinet. With the whole household being disarrayed by the events and Superintendent Seagrave’s cracking his case, into the disappearance of the Diamond the mystery is in full swing. This section is present quite differently, in the American Harper’s Weekly and All the Year Around in Britian. Harper’s Weekly favors putting various images, in the actual story in a larger vertical newspaper format. All The Year Around, is narrower in presentation with the story, to the point where Collins’s name is not even present on his work. Taking the context of the era of Britain’s involvement in India, Collins’s audience would have varied greatly across the Atlantic, making one either more apprehensive or subjective to the content of his novel. In, Albert D. Pionke’s article, they state by “Offering readers a fictional ‘Hindoo conspiracy,’ Collins deploys…temporal and spatial doubling, in a way that forces readers to reexam-ine Britain’s role in the Mutiny” (110). This statement connects greatly with the novel, as the Indian people although are presented through their stereotypes (i.e. The Three jugglers with their clothing, demeanor, etc.), but at the same time are given a chance of defense based on the prologue, which is not seen in history. By having this possibility of questioning a “great” nation’s conduct in a foreign country, it forces one to grapple with ideas of morality and most of all, what is right to. Despite being the pivotal point in the narrative where the action begins, Collins is seen to have more agency in Harper’s Weekly, through the various images and overall display, thus proving that the era’s context has a huge impact on how his work was received in the counter publication.

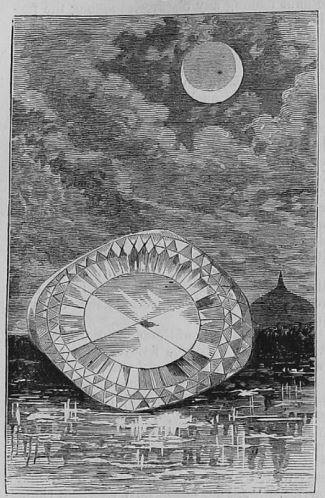

Viewing the first illustration, it is cleverly placed before the actual text and uses the concept of perception to portray the illusion of importance of the stone. Looking at the stone itself, it falls out of the stereotypical rounded diamond, leaving the impression of it actual weight and uses its “larger than life” size/placing to force the reader to pay clear attention to it. Looking beyond the diamond, the next image that is well noted is the actual moon. Taking context, from the Prologue the Diamond is name “The Moonstone” based on its relation to its yellow color and it being adorned on an Indian God that is associated with the moon (Collins 1-2). In particular, the moon is in its Waxing Cresent phase showing the start of a new phase, where the reader finds the diamond now far from its original home. Looking at the right side of the diamond, a dome building is present and taking context of India, the image can imply that it is the Taj Mahal known for its unique shape. According to UNESCO the Taj Mahal was “built in Agra between 1631 and 1648” which predates the publication of this novel (np). By using such a recognized symbol, Collins is enabled to further exotify the gemstone, honoring its roots. This fact is very important when looking at the absence of this image in the Britain publication of The Moonstone. Pionke in his work alludes to The Moonstone being inspired by real life events based on Collin’s Preface mentioning “the Koh-i-Noor diamond” which was “a recent addition to the English crown jewels” (122). This event would explain why the illustration is absent in the British Periodical, as it would be seen as a direct insult to the Crown and the actions Britain as a nation was taking, essentially flawing them of their morality. By having it placed in the American Publication, it gives the reader a chance to appreciate the origins of the diamond and point out perhaps, its exoticism in how it does not fit into British high culture, as it is not just a gemstone; it holds memories of its origins through Religion and holds sentimental value of it being adorned on to an Indian God.

The next illustration comes forth after the diamond has disappeared and gives clues perhaps to what has/will happen to it. The first important part to notice is that the diamond is was placed in an “Indian Cabinet”, which is an interesting situation. After being removed from its homeland of India, the diamond is yet again introduced into a structure that is from the place, but yet removed once again from its “safety”. This rather absurd scene calls for their American Reader, to recall the events of the Prologue once again through a theft in image format. Through viewing Betteredge’s hands with his keys, it makes this scene look impossible, as how could one enter and remove such a precious item without keys or signs of a break in. That implies that the culprit must be someone of the household, as who else could maneuver such a risky mission. Rachel in this scene is placed quite interestingly as well in comparison to Betteredge and Penelope. Her expression almost looks like she does not want the two there poking around there, rather she would have them out. In addition to that, her right hand is placed upon her chest symbolizing one of two possibilities. The first is that this is the place where she placed The Moonstone the evening before during her banquet, so the absence of it makes her feel anxious. The second interpretation according to Pionke is “Rachel’s jewel represents her virginity, which is taken from her on her eight-eenth birthday against her will in a symbolic rape scene by her favor-ite suitor…” (123). Although it is revealed later on Franklin had entered her room, her face and how she is holding her clothing suggests that she is trying to hide something, and this answer maybe it. By being absent in the Britian periodical, it prevents the reader there to take in this second interpretation as they are not given visual cues to something of that nature occurring, thus keeping with the innocence of Rachel’s Virginity and keeping her as a virtuous young lady keeping the reading away from violating societal norms.

After the ending of the section on a cliff hanger, the reader is pulled into a poem called "Right”. As the name suggests, the work dives into the concepts of morality and the power that the word holds. Reading this poem by starting with The Moonstone, the concepts of righteousness as on the tip of the reader’s mind, as it just witnessed a heinous crime of theft. However, that theft runs through the veins of blood and toil when contemplating the diamond’s Indian origins. The third stanza is interesting as well as it can refer to the British Monarchy using its diction of “royal” and “victors” (Lines 13,17) as it was, they who secured the diamond for their empire (the Koh-i-Noor diamond). By excluding this poem in the British Edition, it would prevent the reader to connect the actions of Chapter Eleven to this questioning of what is Right. Looking further, down the poem writes “Building our temples to the Lord” (Line 22) which would be ironic considering how The Moonstone was taken from such a Holy place to begin with. By taking this “wealth” away from its home nation to build Britian suddenly becomes justifiable. On the contrary, by being placed in the American edition, this poem serves almost as this buffer point for individuals to contemplate the actual predicament of the diamond; was it only stolen from Rachel or rather was it even hers to begin with? By placing it here, with the context of the era, it seems that the poem can be used as a call to action/a moment to contemplate how flawed the Imperial Power is. With America being a nation that recently became independent, this feeling would be able to travel freely in the reader. If they follow suit with this idea, they enable the last stanza to come true as they embody qualities of their “Lord” and not the “Right” defined by people’s greedy terms.

Travelling lastly to All The Year Around, its structure is quite interesting in comparison to the American Publication of The Moonstone. Looking at the periodical as a whole one section did stand out, the short story of “General Falcon” being located right after The Moonstone. This story takes place in Venezuela, with the narrator going to meet the fabled “General Falcon”. After various interactions with the narrator, his Spanish Friend and General Falcon himself, the reader is enabled to see the true side of these people, as they are not as barbaric as they seem. True they may have moments that might make the reader question their morality (i.e. Madame R. and her child’s red hat), it is seen that these people are civil to be functioning as a society (200). The key part is that a diamond is also mentioned here where the narrator states, “…I was shown the diamond star he wears…and his order of Libera-tor. ‘So much,’ thought I ‘for equality, republican simplicity, and all that sort of thing”. This statement is key, as the narrator gives his opinion in the matter, whereas the reader is given time to decide whether they believe his claim or not. Tying this idea back to The Moonstone, the first accused suspects are the Brahmins from the night prior by Franklin Blake, which is quickly taken up by the rest of the household (Collins 195). This idea of blaming, Indians shows racism as there is no concrete evidence to their actions, rather their skin color is enough. However, by adding the story of “Captain Falcon”, it challenges this notion as despite being from a foreign land if the leader of the Venezuelan people can act humane, why can’t the three Priests trying to return their diamond? This is supported by Pinoke observations of “doubling” where it “not only elevates the Indians, it also diminishes the English…, the three Brahmins…can commit murder and still appear as le-gitimate agents of the restoration of social order” (125). By viewing it through this lens, the story of “General Falcon”, then becomes a subtle way to humanize the Indians and forces the reader to grapple with the of what is “right”

Conclusion

Coming all together, all of the illustrations, poems and short stories play a crucial role into how a novel is perceived. By adding them they can open new frontiers of interpretations coming from underlying messages and investigation in part from the reader. If both the publications used the material discussed above, it would further enhance the reader's understanding of the nature of the novel. This would enable this work to become more than fictional, rather it calls upon society to re-evaluate its core values and what is actually deemed important through a diamond stolen through bloodshed and then taken once again. In terms of Chapter Eleven, in relation to the whole narrative, it is so important that without it, the events of The Moonstone would cease to transpire. Without the theft, the story would have been greatly reduced to a mere few chapters, to the ending hinting that Franklin and Rachel would marry. By the gemstone not being stolen, characters such as Sergent Cuff, Ezra Jennings and yes even Ms. Clack, would cease to exist as their roles would not be required to push the narrative forward. True by not having the stone stolen, the ending could have been a lot happier with Rachel possessing The Moonstone but based on what this story is inspired from (the Koh-i-Noor diamond and the Indian Mutiny), it would not bring justice to Indians who had it stolen from them. Pinoke perfectly summarizes this point by stating from the view of the Mutiny that, “…The Moonstone issues a challenge to ear-lier racist and imperialist responses to the rebellion by literally re-vealing that at work behind the dark mask of disorder and death is the white face of England” (131), proving that if Rachel kept the diamond would be more detrimental for her and those it was taken from. So by taking it away it allowed for an almost “happily ever after”, she is freed from taking that responsibility of the history of the diamond and is able to spend her days with Franklin. Something that Collins was inherently implying and hoping for to happen in real life with the Koh-i-Noor diamond.

Collins, Wilkie. “The Moonstone: Chapter XI.” Harper’s Weekly, vol. 12, no. 580, Feb. 1868, pp. 85–87. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=h9m&AN=66926458&site=ehost-live.

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone. Edited by Francis O’Gorman, Oxford University Press, 2019.

"GENERAL FALCON." All The Year Round, vol. 19, no. 459, 1868, pp. 199-202. ProQuest, https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-periodicals%2Fgeneral-falcon%2Fdocview%2F7903204%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D9838.

“RIGHT.” Harper’s Weekly, vol. 12, no. 580, Feb. 1868, p. 87. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=h9m&AN=66926468&site=ehost-live.

THE AUTHOR OF THE WOMAN, IN WHITE. "THE MOONSTONE." All The Year Round, vol. 19, no. 459, 1868, pp. 199. ProQuest, https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-periodicals%2Fmoonstone%2Fdocview%2F7860025%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D9838.

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. “Taj Mahal.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre, whc.unesco.org/en/list/252/. Accessed 24 Nov. 2024.