Part 8 - Jorja Reid

The publication of Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone in two different magazines, All the Year Round and Harper’s Magazine offers insight into how the text would have been perceived differently in the United States than in the United Kingdom. While the British All the Year Round presented the novel in a minimalist format that emphasized literature as a moral and intellectual pursuit, the American Harper’s Magazine surrounded the text with advertisements and illustrations, embedding it within a vibrant commercial and visual culture. These contrasting publication strategies highlight divergent attitudes toward literature’s role in society: the British framed it as an elevated, almost sacred art form, while the American approach embraced literature as an integral component of mass culture. Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone, published in the minimalist All the Year Round in Britain and the advertisement-rich Harper’s Magazine in the United States, highlights how transatlantic publication practices shaped literary engagement. These contrasting formats amplify the novel’s exploration of class, gender, and disability, with Rosanna Spearman’s portrayal exposing societal anxieties about marginalized identities in both cultural contexts.

For American readers of Harper’s, the contrast of the eighth installment of The Moonstone with an advertisement for musical instruments was representative of the United States’ rapidly expanding commercial landscape in the nineteenth century. Such commercials, this ad for organs and melodeons included, represented the growth of consumerism and entrepreneurial drive in American culture, where music and musical instruments became more accessible amongst the middle class. As Penne Restad notes, the consumer, in this context, "drifts through the literature... sometimes appearing as a singular being that acts in humanly contradictory and unpredictable ways, and sometimes as a cogent participant in the synthetic aggregate known as 'consumers'" (770). The commercial served to further the idea that consumers are not passive, but are active participants in the economy who continuously balance their desires with societal norms. Moreover, the vibrant presence of advertisements in Harper’s amplified the magazine’s role as a place for both a literary culture and commercial culture. Restad further explains that nineteenth and twentieth-century magazine advertisements “reveal ways in which, at least in the imagination of ad men, purchases transform people into objects and objects attain characteristics of people,” prompting new models of what a consumer is and does (770). The advertisement for organs and melodeons symbolized not just a marketplace for goods but a broader narrative of self-expression and upward mobility, which resonated with the values of a rapidly modernizing society.

This advertisement reflects not only American consumerism but also broader ideas surrounding self-expression through music. This musical context resonates with Sergeant Cuff’s peculiar habit, mentioned in both chapters thirteen and fourteen, of whistling “The Last Rose of Summer,” a tune he hums in the rose garden before he spots Rosanna, and after interrogating her and the servant’s involvement in the mystery (Collins 107). Cuff’s whistling is a seemingly mundane action, yet it is representative of the tension between the universal language of music with the reality of Rosanna’s social exclusion. “The Last Rose of Summer,” composed by Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst in 1864 is a sullen and melancholic song, which is symbolic of Rosanna’s isolation and unrequited love for Franklin Blake. This song further solidifies her as a tragic figure within a rigid social hierarchy.

This advertisement for a Neuralgia pill promising a cure for all nervous diseases in Harper’s Magazine further highlights a distinctly different cultural and literary experience for American readers compared to their British counterparts reading All the Year Round. Harper’s combined serialized fiction with advertisements for remedies, household goods, and lifestyle products, shaping a new kind of reader engagement that Linda Hughes describes as “an interconnected web of discourse” that was ideological, political, visual, and commercial (3). The Neuralgia pill advertisement catered to an American society dealing with fast–paced industrialization, and the new psychological toll of modern life. For Harper’s readers, this commercialized context coincided with The Moonstone’s thematic exploration of disability, particularly as embodied by Rosanna Spearman. Many of the novel’s most provocative themes—gender, disability, and class—cluster around Rosanna, since “the presence of disability in Victorian fiction indicates more than a mere reflection of actual disabled persons in the culture” at the time, it also points to “an underlying anxiety and ambivalence regarding this presence, a grappling with identity, a desire to experiment with places and roles” in a fictional world (Rodas as qtd. in Mossman 485). The portrayal of Rosanna, along with the broader exploration of disability in the novel, evokes the question, how were such conditions perceived and handled during this time? Mark Mossman explains that “the abnormal body is the “raw material” or the instrument or prosthetic device through which a compulsory normative center renders and frames the irrational, deviant, resistant “disorder” that “plagues” the body of the society as a whole” (Mossman 485). This understanding amplifies the treatment of Rosanna’s disability in The Moonstone, where her physical difference and criminal past make her the centre of social discomfort. For instance, Sergeant Cuff’s comment, “it isn’t very likely, with her personal appearance, that she has got a lover...poor wretch,” (Collins 109) underscores Victorian anxieties about disabled women’s place in normative structures of love and desirability because “women with disabilities have been struggling with the oppression of being women and individuals with disabilities in abled and male-dominated societies” (Mounisha and Vijayalakshmi 1889). The advertisement’s promise to solve mental distress, contrasts with the novel’s depiction of Rosanna’s unfixable social alienation. This pairing in Harper’s encourages readers to reflect on disability as both a medicalized condition and a marker of systemic inequity.

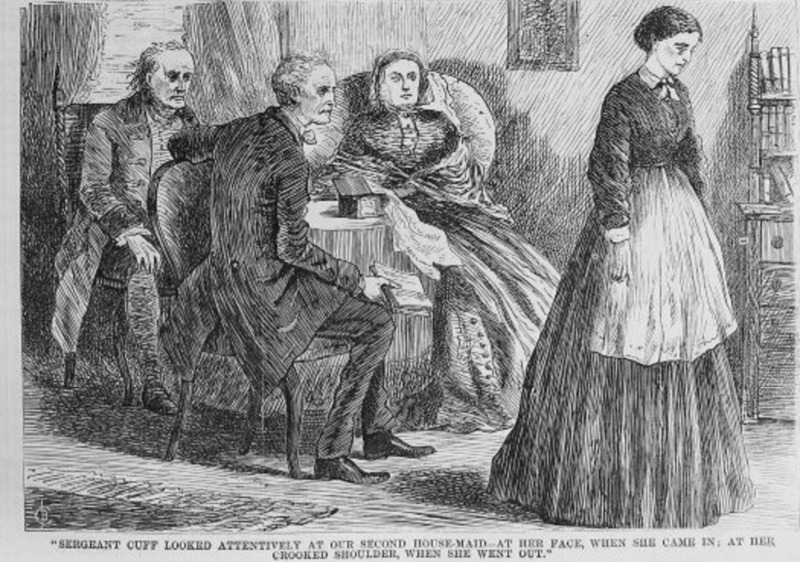

While the British periodical, All The Year Round, relied solely on textual content to engage readers, emphasizing imagination and literary interpretation, Harper’s incorporated “sixty-six intricate illustrations, printed on large 16 ½ by 11 ½ inch sheets,” that profoundly affected the narrative’s unfolding and interpretation (Leighton and Surridge 209–210). These visuals, “created by at least two, possibly more, illustrators,” added a sensational and “dramatic layer to the already complex narrative structure, enhancing its themes and shifting the portrayal of gender, disability, class, and race” (Leighton and Surridge 207, 210). The illustrations in Harper’s did more than complement the text; they became fundamental to the storytelling, functioning as plot elements that influenced the narrative's meanings (Leighton and Surridge 210). For instance, the depiction of Sergeant Cuff observing Rosanna Spearman in this illustration is captioned with the scene it is depicting: “Sergeant Cuff looked attentively at our second house-maid... at her face when she came in; at her crooked shoulder when she came out” (Collins 106). This comment accentuates Rosanna’s unassuming social position as a disabled woman, servant, and as readers learn in this installment, a criminal. Sergeant Cuff immediately recognizes her and explains: “The last time I saw her…she was in prison for theft” (Collins 106). This revelation not only adds to Rosanna’s marginalization but also reinforces the societal prejudices that define her solely by her past transgressions and physical appearance. By highlighting her criminal history, Collins acknowledges the societal structures that deny individuals like Rosanna any chance of redemption or complexity beyond not only their physical disabilities, but their criminal past as well. Her criminal past, physical disability, and unrequited love for a man of much higher social class challenge Victorian norms and destabilize traditional boundaries (Leighton and Surridge 222; 227).

Sergeant Cuff makes another observation, later on in chapter fourteen: “hadn’t you better say she’s mad enough to be an ugly girl and only a servant” (Collins 110). This statement not only emphasises the idea that “Rosanna must be pitied because she is physically different and pathetically so – she is female, poor, alone, and most of all, deformed,” but also invites readers to confront how Rosanna’s intersecting identities render her invisible within Victorian hierarchies (Mossman 488). This installment of The Moonstone is also when readers discover Rosanna’s criminal past. These visual representations magnify her liminal status and increase reader’s sympathy for her situation. Ultimately, Harper’s illustrations not only captivated American readers but also deepened their interaction with the text’s sensational elements.

The presence of only one advertisement in All the Year Round, promoting other works by Charles Dickens: “George Silverman’s Explanation” and “Holiday Romance” contrast with Harper’s Magazine, where three pages of advertisements surrounded the novel’s installment. This discrepancy highlights a critical difference in the cultural and economic positioning of serialized fiction. For British readers, the self-referencing advertisement in All the Year Round reinforced the journal’s high status of literature and its editor’s brand. Ironically, “Dickens viewed American print culture as an invasive species throughout the 1840s, becoming an outspoken advocate for international copyright protection in the United States,” yet he was still a willing participant in the capitalist elements of American print culture (McIntosh 434). As Hughes notes, “Dickens advertises Dickens who advertises Dickens, bruting the name to at least the third power in print” (8). By promoting his own stories, the journal created a self-sustaining literary world, where the author’s name became synonymous with quality fiction and intellectual engagement. This “multiplier of symbolic capital” invested in Dickens’ brand elevated the periodical above commercial distraction, ensuring an immersive and uninterrupted reading experience (Hughes 8). The limited presence of advertisements maintained a focus on storytelling as an art form, separate from the distractions of business.

In summary, Harper’s integration of advertisements and illustrations not only captivated American readers but also transformed their engagement with The Moonstone. The interaction between image, text, and commerce emphasized the novel’s complexities while inviting reflections on societal tensions surrounding class, race, gender, and disability. By contrast, the restrained approach of All the Year Round upheld Victorian ideals of literature as a sacred intellectual domain. Together, these differing contexts reveal how The Moonstone served as both a literary text and a cultural product, shaped by and reflecting the forces of its transatlantic publication.

Works Cited

Advertisement for Charles Dickens' "George Silverman's Explanation" and "Holiday Romance." All the Year Round, 22 February 1868: pg. 264. Dickens Journals Online,

https://www.djo.org.uk/all-the-year-round/volume-xix/page-264.html

"Chapter 14 Illustration: The Moonstone." Harper's Weekly, 22 February 1868: pg. 117. EBSCOhost - Digital Archives Viewer,

https://web-p-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/ehost/archiveviewer/archive?vid=2&sid=23b29a58-e421-4581-b566-563ce3f6c869%40redis&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#kw=true&acc=false&lpId=NA&ppId=divp0005&twPV=false&xOff=0&yOff=615&zm=2&fs=&rot=0&docMapOpen=true&pageMapOpen=true&AN=66926512&db=h9m

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone. Oxford University Press, 2019.

Hughes, Linda K. “SIDEWAYS!: Navigating the Material(Ity) of Print Culture.” Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 47, no. 1, 2014, pp. 1–30, https://doi.org/10.1353/vpr.2014.0011.

Leighton, Mary Elizabeth, and Lisa Surridge. “The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper’s Weekly.” Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 42, no. 3, 2009, pp. 207–43, https://doi.org/10.1353/vpr.0.0083.

McIntosh, Hugh. “Misreading and the Marketplace: Dickens and Du Maurier in a Commercial Age.” Novel : A Forum on Fiction, vol. 49, no. 3, 2016, pp. 429–48, https://doi.org/10.1215/00295132-3651183.

Mounisha, N., and V. Vijayalakshmi. “Revealing the Commonalities Existing in Depictions of Disabled Female Characters in Prose Fictions: A Study of Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone and Toni Morrison’s ‘Recitatif.’” Theory and Practice in Language Studies, vol. 14, no. 6, 2024, pp. 1888–96, https://doi.org/10.17507/tpls.1406.30.

Mossman, Mark. “Representations of the Abnormal Body in the Moonstone.” Victorian Literature and Culture, vol. 37, no. 2, 2009, pp. 483–500, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1060150309090305.

"Prince & COS Automatic Organs and Melodeons." Harper's Weekly, 22 February 1868: pg. 128. EBSCOhost - Digital Archives Viewer,

https://web-p-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/ehost/archiveviewer/archive?vid=2&sid=23b29a58-e421-4581-b566-563ce3f6c869%40redis&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#kw=true&acc=false&lpId=divl037&ppId=divp0016&twPV=false&xOff=0&yOff=3&zm=2&fs=&rot=0&docMapOpen=true&pageMapOpen=true&AN=66926512&db=h9m

Restad, Penne. “The Third Sex: Historians, Consumer Society, and the Idea of the American Consumer.” Journal of Social History, vol. 47, no. 3, 2014, pp. 769–86, https://doi.org/10.1093/jsh/sht109.

"Turner's Universal Neuralgia Pill." Harper's Weekly, 22 February 1868: pg. 128. EBSCOhost - Digital Archives Viewer,

https://web-p-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/ehost/archiveviewer/archive?vid=2&sid=23b29a58-e421-4581-b566-563ce3f6c869%40redis&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#kw=true&acc=false&lpId=divl034&ppId=divp0016&twPV=false&xOff=0&yOff=619&zm=2&fs=&rot=0&docMapOpen=true&pageMapOpen=true&AN=66926512&db=h9m