Part 29

Introduction

As the Civil War slowly encroached upon America, more and more of the articles published in Harper’s Weekly began to take on a political nature with an increased emphasis on timeliness. As Ashlyn Stewart explains, “Getting news out quickly suddenly mattered more than ever when in the balance of each update from the front lines hung news about the lives of soldiers and the state of the nation” (201). To thus remain competitive amid the flurry of periodicals that often updated daily via telegrams, Harper’s Weekly marketed itself as a historical record, “curat[ing] their content not to be as current as possible but to be as complete and comprehensive. . . as possible” (Stewart 203). Owing to the demands of this wartime context, the continued serialization of Charles Dicken’s novel, Great Expectations, in Harper’s Weekly may thus appear rather unfitting. As a story detailing the life of a boy growing up in Victorian England, it is unclear how Great Expectations aligned with Harper’s Weekly’s goal of keeping a historical record of the war. Such thoughts, however, discredit Great Expectations’ potential as a work of art to emotionally resonate with a wide range of readers in various circumstances. To this end, I contend that when Great Expectations, chapter XLVI, is read within the original publication context of Harper’s Weekly, vol. 5, no. 233, the text comes to reflect anxieties specific to an American readership, which are untranslatable to the UK readership of All the Year Round. Specifically, the publication context of Harper’s Weekly foregrounds the anxiety and hidden danger that Compeyson poses to Pip, capturing the general anxiety American readers felt from knowing the danger the civil war posed to friends and family, while being powerless to know or prevent how that danger might manifest. Such anxiety remains largely novel to a UK audience reading All the Year Round, as apparent by the journal sensationalizing the civil war.

Pip Sits Listening with Dread

The above illustration depicts a moment in Great Expectations, where Pip anxiously worries whether Magwitch has been discovered by Compeyson while awaiting further communication from Wemmick. This anxiety, as represented by the picture, manifests as a fear of the unknown. Consider the darkness which shrouds most everything. Through the thick and heavily concentrated line work, all the fine details of the illustration, from the pictures in the background to the linework on the tablecloth, are blurred. By limiting the reader’s vision in this way, the reader comes to understand Pip’s anxiety in terms of what is unseen. Pip’s knowledge is lacking, forced as he is to wait in his room for second-hand accounts of the world’s occurrences. The source of Pip’s fear remains inaccessible, existing off the page and behind the door to which he looks. Pip looks but he cannot see, forced to let his mind conjure up a host of frightening pictures. The stagnancy of Pip’s anxious waiting becomes active and disturbed as the lines transition from being tightly packed to slightly more spacious, lending the image an almost trembling quality. In contrast to this darkness, is Pip, who remains dangerously exposed. The candlelight collects on his face, rendering him a clear and visible white, such that he sticks out to the reader, and whatever danger might be looking for him. That the illustrator would choose to depict Great Expectations through this anxiety, and in such a visceral way no less, greatly changes the reader’s understanding of the text. For the reader, this image foregrounds Pip’s anxiety in this installment of Great Expectations, specifically as it relates to what one cannot see, yet knows is present

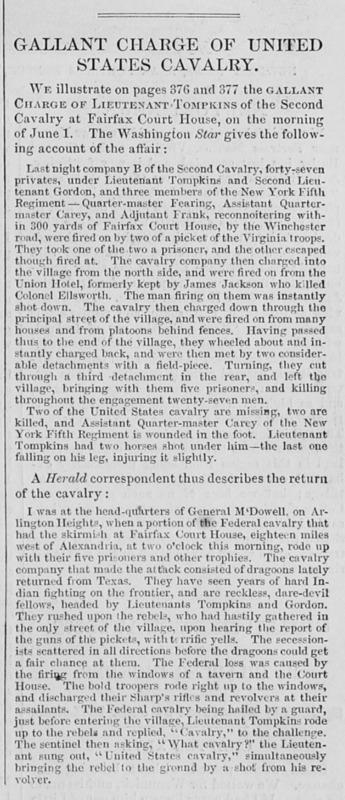

The Murder of Ellsworth

The above item, located on the front page of Harper’s Weekly, illustrates an article published the previous week, detailing the manner in which Colonel Ellsworth was murdered by tavern keeper Jackson. For the American reader, this image and the unseen nature of danger it represents renders the threat of Compeyson, and with it Pip’s anxieties, all the more real. Consider how Ellsworth is unarmed and turned away from Jackson. Not only does this portray Ellsworth as defenceless, but he is unable to see the source of his death even after being shot. Ellsworth’s misfortune is intimately connected to his inability to see the danger that surrounds him. When Pip later remarks how he would “start from [his] bed. . . terror fresh upon [him] that [Magwitch] was discovered” and how he would “sit listening as [he] would, with dread, for Herbert’s returning step at night”, it becomes apparent that Pip’s vision is similarly impaired (Dickens 405). Utterly reliant upon secondary sources for information, Pip is perpetually distanced from, but always reminded of the danger that lurks in the shadows. The anxiety that Pip consequently experiences over fear of Magwitch’s health closely mirrors the audience’s own position in reading Harper’s Weekly. The above illustration reminds the reader that a hidden danger is lurking, but they have no way of knowing whether someone they care for has succumbed to such danger in the downtime between reports. The danger remains viscerally visible to them, like with Pip, but they are powerless to act.

But as much as Pip and the viewer are powerless to intervene in the dangers of the world around them, the opposite is not true. This point is especially emphasized by the framing of Jackson as emerging from the shadows, while Ellsworth is positioned in the lighter half of the illustration. Illuminated by the light coming from above, Ellsworth is visible to Jackson, and thus in danger. While danger may be presented as hidden in this picture, it rises up from the shadows of the stairs to strike at those who remain visible in the light. The anxiety of this knowledge, privy only to the reader, provides a frame for understanding the terror Pip experiences when he realizes that Compeyson was seated behind him during Wopsle’s play. As Pip explains, “I cannot exaggerate. . . the special and peculiar terror I felt at Compeyson’s having been behind me ‘like a ghost.’” (Dickens 409-10). Ghosts, as beings belonging to the realm of the dead, are unique in their ability to haunt and visit the world of the living. So long as a person is alive, however, the world of the dead is inaccessible to them. Just as how Jackson’s bullet thus travels from the shadows into the light, so too can Compeyson cross aisles to prey upon Pip. All the while, Pip, like Ellsworth, has no idea what the ensuing danger looks like. The dangers of the civil war, as depicted through this illustration, render the unseeable, yet omnipresent threat Compeyson poses to Pip, particularly resonant with an American audience.

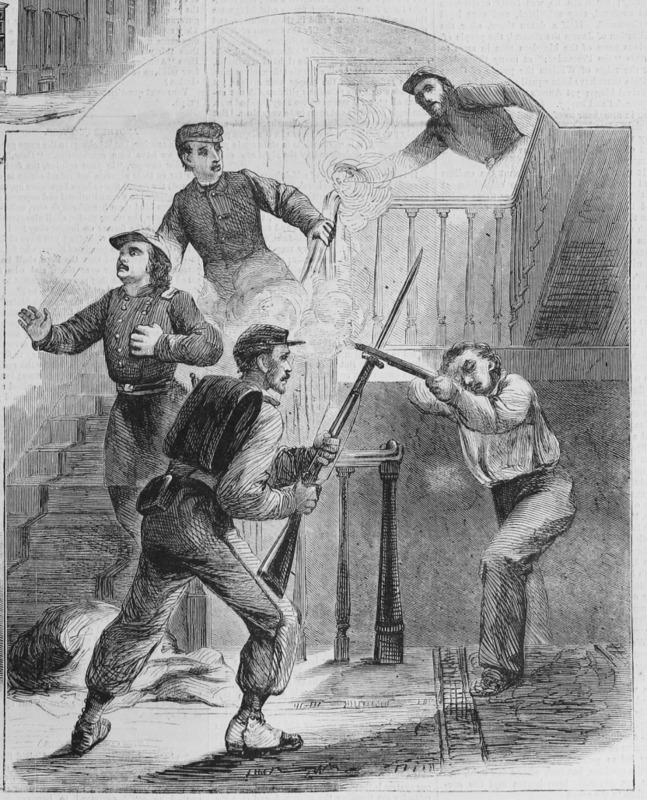

Gallant Charge of United States Cavalry

This syndicated article offers two accounts of a Union cavalry charge at Fairfax Court House, one from the Washington Star, and another from a Herald correspondent. As one of the last articles published in the journal, the narration style of the Herald correspondent, giving events a heroic flair, functions to relieve much of the anxieties produced through reading Harper’s Weekly. Consider the following account the reporter gives of an exchange between a confederate guard and a union lieutenant:

[E]ntering the village Lieutenant Tompkins rode up to the rebels and replied, “Cavalry,” to the challenge. The sentinel then asking, “What cavalry?” the Lieutenant sung out, “United States cavalry,” simultaneously bringing the rebel to the ground by a shot from his revolver. (“Gallant Charge” 381)

Now, regardless of whether this exchange ever actually occurred, it is very melodramatic in its presentation. Through his short witty responses, and the way he exercises violence without contestation, Lieutenant Tompkins is portrayed as a sensational figure of unparalleled dominance. Functioning like a hero straight from a western, Tompkins vanquishes the confederates with ease. Through moments like this, and references to the Union cavalry as “bold troopers” and “dare-devil fellows”, a narrative of the Union’s dominance is crafted, easing the anxieties of the American reader (“Gallant Charge” 381). Their friends and family are in good hands. Such relief, however, is immediately undermined by the depiction of Wopsle’s performance in Great Expectations on the next page. In an effort to relieve the unrelenting anxiety of awaiting new information from Wemmick, Pip decides to attend one of Wopsle’s plays. But despite the rather farcical nature of the performance, Pip is truly distracted, giving a detailed account of the performance in all its haphazard glory (Dickens 406-08). Any relief, however, is quickly undermined by Pip’s previously mentioned discovery that Compeyson was seated behind him. As Pip says, “If he had ever been out of my thoughts for a few moments together since the hiding had begun, it was in those very moments when he was closest to me” (Dickens 410). The illusory effect of Wopsle’s performance has been shattered for Pip as he learns that “however slight an appearance of danger there might be about us, danger was always near and active” (Dickens 410). This realization dramatically changes the meaning of the Gallant charge of the Cavalry on the prior page. Just as how the dangerous reality, fostering Pip’s anxieties, persisted during the performance, so too do the hidden dangers of the civil war persist no matter how gallant the cavalry are portrayed. The reader’s anxieties are momentarily forgotten but never concluded. The fear that Union soldiers, a reader’s friends and family, could be shot like Ellsworth was on the cover page, persists. Thus, within the context of the civil war, not only does this installment of Great Expectations act as a mirror for the audience’s anxieties, it contributes to the reader’s understanding of their own anxiety. Within the publication context of Harper’s Weekly, Great Expectations forces the reader to confront the perpetuating danger haunting the articles with which they placate themselves.

Naval and Military Traditions in America

When we turn to All the Year Round, the presentation of anxiety in Great Expectations as stemming from an imperceivable, yet omnipresent danger, resonates much less with a UK readership. This is evident through consideration of the above essay in All the Year Round, which offers a first-hand account of American Naval and Military traditions. One noticeable feature of this work is the comparative use of America to perpetuate endlessly deprecating remarks made about Europe. Whether because America’s most opulent palace (the white house) is “much smaller and less pretentious than half the Inigo Jones’s mansions that stud our green English parks” (“Naval and Military Traditions” 286), or because “the small American army is, in fact, not kept to support rich men’s sons” (“Naval and Military Traditions” 288), there is no end to the list of Europe’s shortcomings. Through this constant awareness of Europe’s shortcomings, anxiety in Great Expectations is altered for the UK reader, such that it concerns the guilt of participating in a corrupt social system. Consider when Pip arrives at Jagger’s house and comments on how “the pair of coarse fat office candles that dimly lighted Mr. Jaggers as he wrote in a corner, were decorated with dirty winding-sheet, as if in remembrance of a host of hanged clients” (Dickens 412). This implicit remembrance of the clients Jaggers has helped put to death does not stem, but guilt. After all, the ‘winding-sheet’, or burial shroud, that the melted candle grease is metaphorically represented as, is dirtied. In this way, the very light which allows Mr. Jaggers to see is tainted. His vision, as a lawyer intimately implicated in an unjust system of criminal justice, is perpetually haunted by all the clients whose deaths he participated in. For UK readers, this perversion of the very light through which one sees represents the social anxiety experienced from passively taking part in a corrupt social system. Just as how the author of Naval and Military Traditions in America, could not reflect upon America without constantly making reference to the sordid state of England, so too does England’s corruption permeate the landscape of Great Expectations.

This anxiety induced by the publication context of All the Year Round, however, is incompatible with the anxiety experienced through reading Harper’s Weekly. By degrading Europe through comparisons to America, the above essay fostered an idealized depiction of America. To this end, the author barely acknowledges the ongoing American Civil War, instead commenting on how the retelling of legends will be used “to rouse the North and to consecrate the standards dusty with so long and so holy a peace.” (“Naval and Military Traditions” 288). By interpreting current events in terms of the past and oneself, the author is disconnected from the lived experience of the civil war. This self-referential perspective and anxiety, present as it is in All the Year Round, thus comes to distance the UK reader from the anxiety Pip experiences while constantly aware of a danger he cannot see. The passive experience of using secondary information to engage with a world that threatens the lives of those one loves is not immediately apparent for the UK reader. Through sensationalizing the Civil War through its own anxieties, All the Year Round novelizes the visceral connection American readers formed with Pip.

Conclusion

In conclusion, by considering how Great Expectations was read in the publishing context of Harper’s Weekly and All The Year Round, what emerges is two radically different interpretations of the text. For an American readership, Great Expectations encapsulated the anxieties of the civil war, where readers, through publications like Harper’s Weekly, were acutely aware of an ephemeral danger that threatened their friends and families yet remained powerless to identify and combat it. The danger presented to Pip through Compeyson, constantly haunting his thoughts without giving Pip any certainty about how and where the danger will manifest itself, mirrors the reader’s own position. As for All the Year Round, however, the potency of this anxiety is lost. British readers, removed as they were from the civil war, were instead called to reflect upon the corruption of their own social system which is immediately present in Great Expectations. While the events of Great Expectations may thus seem largely removed from an American Audience, on an emotional level, they are much closer, functioning to foster a better understanding of the audience’s own anxieties during the civil war.

Works Cited

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations, edited by Graham Law and Adrian J. Pinnington, Broadview Press, 1998.

"Gallant Charge of United States Cavalry." Harper's Weekly, vol. 5, no. 233, Harper & Brothers, 15 June 1861, pp. 381. American Antiquarian Society (AAS) Historical Periodicals Collection ‑ Series 4 Publications. https://web‑s‑ebscohost‑com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/ehost/archiveviewer/archive?vid=3&sid=b2637ea8a98d‑4a00‑b076‑e17136b4be4c%40redis&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#kw=true&acc=false&lpId=divl1&ppId=divp1&twPV=&xOff=0&yOff=0&zm=fit&fs=&rot=0&docMapOpen=true&pageMapOpen=true&AN=67218270&db=h9k.

"Naval and Military Traditions in America." All the Year Round, vol. 5, no. 122, 15 June 1861, pp. 285-288. Dickens Journal Online. https://www.djo.org.uk/all-the-year-round/volume-v/page-285.html.

McLenan, John. "Pip Sits Listening With Dread." Harper's Weekly, vol. 5, no. 233, Harper & Brothers, 15 June 1861, pp. 382. American Antiquarian Society (AAS) Historical Periodicals Collection ‑ Series 4 Publications. https://web‑s‑ebscohost‑com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/ehost/archiveviewer/archive?vid=3&sid=b2637ea8a98d‑4a00‑b076‑e17136b4be4c%40redis&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#kw=true&acc=false&lpId=divl1&ppId=divp1&twPV=&xOff=0&yOff=0&zm=fit&fs=&rot=0&docMapOpen=true&pageMapOpen=true&AN=67218270&db=h9k.

Stewart, Ashlyn. “Creating a National Readership for Harper’s Weekly in a Time of Sectional Crisis.” Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council, National Collegiate Honors Council, 2018, pp. 173-209. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nchcjournal/578.

"The Murder of Ellsworth." Harper's Weekly, vol. 5, no. 233, Harper & Brothers, 15 June 1861, pp. 369. American Antiquarian Society (AAS) Historical Periodicals Collection - Series 4 Publications. https://web‑s‑ebscohost‑com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/ehost/archiveviewer/archive?vid=3&sid=b2637ea8a98d‑4a00‑b076‑e17136b4be4c%40redis&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#kw=true&acc=false&lpId=divl1&ppId=divp1&twPV=&xOff=0&yOff=0&zm=fit&fs=&rot=0&docMapOpen=true&pageMapOpen=true&AN=67218270&db=h9k.