Part 10

Charles Dickens, and Victorian novels in general, have an indisputable tendency to include topics of misery, poverty, death, and abuse in their stories. Consider Great Expectations, for example; orphans, abandoned wives, and abuse victims litter the pages. While these situations may be unfavourable, they can provide valuable insight into the historical, political, and societal state of 19th century life. For example, Pip’s lack of relations can be used to understand Victorian child and infant mortality rates while Mr. Jaggers’ character can provide insight into 19th century England’s judicial system. The tenth part of Great Expectations, however, focussed neither on Victorian England’s lawyers or orphaned children, but on female abuse as a means of silencing “unruly”, “loud”, or “wicked” women. Since “attitudes toward violence against women are formed by a wide range of social processes” (Flood and Pease 126), it makes sense that typical behaviours, like stubbornness or overzealousness, were gendered and, thus, considered inappropriate for a woman to portray. When reading the 10th serial release of Great Expectations in the context of a 19th century American magazine, Harper’s Weekly, themes, topics, and concepts are accentuated in a way that would have otherwise not been possible if the novel were read independently. Ads, poems, illustrations, and even jokes, were published with the intention of being read conjunctively with Great Expectations. In light of this reading, an emphasis appears to have been placed on female suffering and abuse, where jokes and poems, either explicitly or otherwise, open a discussion regarding the life-changing assault endured by Mrs. Joe at the hands of Orlick.

Humors of the Day

The section titled “Humors of the Day” in Harper’s Weekly published many jokes with women as their punchline. The first joke of the section (see above) reads: “If a pretty Young Lady talked too much would it be ungallant to admire her, but to qualify it by saying that her beauty was un peu trop prononcé” (Unknown 67). By reading this joke before part 10 of Great Expectations do readers prepare to encounter what happens to women that are “un peu trop prononcé”. Now, when contrasting this “joke” to the abuse endured by Mrs. Joe as a result of her attitude, it does not seem too funny. “Un peu trop prononcé” is French for “a little too pronounced”, meaning that if a woman is too opinionated, loud, or talkative, she will appear less beautiful. The evident preference for women of a quiet and reserved nature raises the question: why do men prefer quiet women? Is it because they are easier to control and have less of a tendency to question authority? Despite being completely harmless, exhibiting behaviour that is “un peu trop prononcé” is deeply frowned upon by patriarchal societies as “there is a powerful association between attitudes towards violence against women and attitudes towards gender” (Flood and Pease 128). That is, being loud, boisterous, and opinionated is equated to being a man and so, seeing a woman portray manly traits is considered a threat and thus worthy of violence. In this case, Mrs. Joe speaking on behalf of her husband was considered an offensive act of defiance, as she is considered to be going against the female norms. Women are not expected to speak out of turn, let alone boss a man around, so she was dealt with appropriately. Her lack of respect for men and overzealousness are what ultimately cost her her livelihood, as she was beaten by Orlick as a demonstration of his promise to “hold [her], if [she] was [his] wife” (Dickens 148). Jokes made at the expense of women are hardly ever funny, as the suggestive undertones are, unfortunately, based on real life events endured by women every day.

Destroying the Enemy's Works

The jokes do not end there, however, as another joke titled “Destroying the Enemy’s Works” (see above) could be read as an eerie metaphor to the altercation between Mrs. Joe and Orlick. This “joke” is less explicit than the first one, but when considering the time of its publishing, it appears as though it was carefully selected to complement part 10 of Great Expectations. The soldiers could be interpreted as Orlick, the watches and clocks as Mrs. Joe, and the Emperor's Palace as Joe Gargery’s home because he is, quite literally, the soldier’s superior. Orlick, or the soldier’s, decision to destroy the watches in the interest of simply “killing time” radiates the same energy as “just because he can”. The power imbalance between men and women is glaring, as women are illustrated as being valuable, yet fragile, while men are equated to being powerful and violent. A watch stands zero chance against a soldier, as it has no ability to run away, defend itself, or scream for help. Since “the relationship between adherence to conservative gender norms and tolerance for violence has been documented among males” (Flood and Pease 128), it makes perfect sense that the soldiers would inflict a random act of violence against unsuspecting inanimate objects, for they perceive the world as one where they must be violent in order to certify their manliness. The soldiers knew the watch would be an easy target as it is completely unable to fight back, and they took full advantage of that, much like how Orlick took full advantage of his manly superiority by striking Mrs. Joe back into submission “with something blunt and heavy, on the head and spine” (Dickens 153).

Riddle for the Social Circle

The last joke worth mentioning before moving onto the poetry section of Harper’s Weekly is titled “Riddle for the Social Circle” (above), where the author questions when women are most like poachers, to which they respond “when she has her hair in a net” (Unknown 67). This joke is a double edged sword in that no matter the way it is interpreted, it is harmful to women. The author is essentially arguing that women have their hair in nets either to 1. Work in the kitchen or 2. As a result of failing at poaching. Poaching is a hunting profession dominated predominantly by men, and to say that the only time a woman would ever mimic a poacher is with her hair in a net conjures the image of a clumsy, wanna-be, female poacher tripping over her supplies and getting tangled in the netting. The only other time a woman has her hair in a net is when she is working in the kitchen and so, by failing at “manly activities” is the author essentially saying that women should belong in the kitchen and stick to what they know. When considering this argument in terms of Dickens’ work, it appears that Mrs. Joe is the female poacher, trying to do Joe Gargery’s job for him by disciplining Orlick, but ultimately, failing and catching herself up in the netting. “I wish I was his master!” (Dickens 147), Mrs. Joe exclaims, sealing the deal of her unfortunate fate. Let it be known that “female victims of domestic violence are judged more harshly where they are perceived to have provoked aggression, for example, by being verbally aggressive” (Flood and Pease 129), so it matters not that Mrs. Joe did not do anything illegal, for her verbal defiance was enough to leave her trapped and tangled in the net. Had she just stuck to her female duties, she would not have ended up in this situation. By placing this joke before Dickens’ chapter do we as an audience prepare to rationalise Mrs. Joe’s bed-bound state with arguments like “she should have known better to intrude” or “she shouldn’t have gotten involved in men’s business”.

Too Late

Moving on from the abundance of jokes, there was an equal abundance of poetry in the February 2nd publication of Harper’s Weekly, but the difference is that the poems appear after the 10th part of Great Expectations, while the jokes appear before. The jokes appear to set the stage for what’s to come, while the poems shed light on the pain endured by both Mrs. Joe and Pip. One of the poems, titled “Too Late” (see above), is the first piece of sympathy to Mrs. Joe’s character due to her finally fitting gender norms by exhibiting ideal qualities like submissiveness, purity, or modesty. The poem illustrates the peaceful death of a woman in bed, but with the use of demeaning words like “helpless” or “hopeless”, ultimately undermining the woman and painting her as some frail creature worn down by life, finally being freed by death. Female suffering is something that is oftentimes romanticised by men, as there appears to be less of a concern with her pain and more of a focus on her outward appearance. Sure, the woman is dying, but she’s peaceful and finally quiet, so what does it matter? Mrs. Joe’s unfavourable character being, quite literally, beaten out of her, is the moment the reader, and Pip, can finally find it in their hearts to sympathise with her suffering. The unnamed woman in the poem is also never afforded the opportunity to speak on her own behalf, which is similar to Mrs. Joe, where she is beaten so severely that it became “necessary to keep [a] slate always by her, that she might indicate in writing what she could not indicate in speech” (Dickens 155). Both women are, in this case, silenced and regarded as some pitiful, helpless creature. What’s more, this poem could potentially be foreshadowing what is to come of Mrs. Joe…

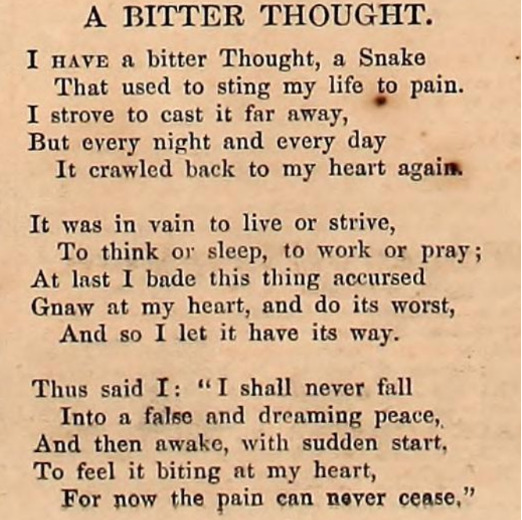

A Bitter Thought

Another poem worth discussing, titled “A Bitter Thought” (above), could have been written from Pip’s perspective. Throughout part 10, Pip laments about the heavy guilt he experiences in light of his sister’s physical assault as he was “at first disposed to believe that [he] must have had some hand in the attack upon [his] sister” (Dickens 153). Despite finally being free from Mrs. Joe’s firm grasp, Pip can’t seem to let go of the blame. Throughout the poem, the writer compares the experience of “a bitter thought” to a snake that wraps itself around the individual’s heart, gnawing and biting. In this case, Pip is the narrator while Mrs. Joe is the snake. Despite not physically being able to control Pip anymore, Mrs. Joe is still with him in his heart and his mind, infiltrating his thoughts, poisoning him with anxiety, and “sting[ing] [his] life to pain” (Unknown 78). By comparing Mrs. Joe to a snake is the poet illustrating her inability to be a pure woman and in turn, justifying the beating she endured, as “perceptions of the legitimacy of men’s violence… are constituted through agreements that men should be dominated in households… and have the right to enforce their dominance through physical chastisement” (Flood and Pease 128). This poem also provides valuable insight into the difficulties of overcoming abusive, power-imbalanced relationships, and, when read conjunctively with this part of the novel, can we as readers understand the challenge Pip faced of not only forgiving himself for his sister’s attack, but finding the strength to leave his sister for good.

By discussing the topic of female violence with poems and jokes does the seriousness of the topic become watered down and twisted into a sort of cruel, offensive joke. Domestic abuse is not afforded the respect, accountability, and seriousness it deserves, which, ultimately, continues the cycle of abuse. Until men are held accountable for their wrongdoings, they will continue to wreak havoc on the female species. A joke comparing women to a stupid poacher or an inanimate object will do little in humanising their characters, but instead justify the violence and assault endured at the hands of their male counterparts. By warming up the reader with jokes aimed at dehumanising women and then closing the section with poetry that belittles female suffering does Harper’s Weekly send the message that beating women, like Mrs. Joe, is a completely acceptable form of punishment if we wish to control those who are “un peu trop prononcé”.

Works Cited

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. Broadview Press, 2022.

Flood, Michael, and Pease, Bob. “Factors Influencing Attitudes to Violence Against Women.” Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 2009, pp. 125-142, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26636200.

Unknown. "A Bitter Thought." Harper's Weekly, 2 February 1861, p. 78.

Unknown. "Destroying the Enemy's Works." Harper's Weekly, 2 February 1861, p. 67.

Unknown. "Humors of the Day." Harper's Weekly, 2 February 1861, p. 67.

Unknown. "Riddle for the Social Circle ." Harper's Weekly, 2 February 1861, p. 67.

Unknown. "Too Late." Harper's Weekly, 2 February 1861, p. 78.