Part 12

Fashion in the Victorian Era and Dickens' Great Expectations

Siwar Abeid

Charles Dickens' Great Expectations was published as a serialized novel in the Victorian era. One of its publishers, Harpers Weekly, integrated various articles and advertisements that were scattered around each publication. Most pieces carry some relevance and connection to the overall context of the novel, whether it be to the plot of the story itself or even a general link to the historical context at the time. In chapter nineteen of the novel, Pip prepares for his big move to London. He progressively becomes aware of the stark differences between his humble upbringing and the lavish lifestyle of the upper class. In his book, The Cut of His Coat: Men, Dress, and Consumer Culture in Britain, Brent Shannon explores how “despite repeated acknowledgments that fashion was a vain, silly, and even wicked pursuit… [it is] insisted that it was an essential social convention to which meticulous attention had to be paid” (36). This progressive social acceptance Victorian society moves towards is seen in Dickens’ novel and portrayed throughout the articles in Harper’s Weekly magazine, which is an American publishing company. The Harper’s Weekly February 16, 1861, publication of Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations emphasizes the prevalence of class systems by surrounding the chapter with various articles that acknowledge the beauty standards and expectations of a higher-class society at the time. The integration of advertisements also reveals the working conditions of the lower class and the progression of society’s interest in men’s fashion during the Victorian era.

Harper's Weekly and Working Farmer

One of the primary class systems explored in Great Expectations is the distinction between the upper and lower classes. These differences are evident in the contrasts between the wealthy Miss Havisham and her daughter Estella and Pip’s humble background. One of the advertisements in this publication promotes a working opportunity, titled “Harper’s Weekly & Working Farmer, for $240 a year” (Harper’s 112). This advertisement helps emphasize the working conditions and their significance in the novel's plot. Pip’s experience as a blacksmith’s apprentice embodies what hard work and poor working conditions the lower class faced at the time. As this advertisement came up in this edition of Harper’s Weekly, the chapter focused on Pip’s working conditions as he was excited about moving to London and leaving behind the challenging work and lifestyle he initially lived: “No more low wet grounds, no more dykes and sluices, no more of these grazing cattle…I was for London and greatness: not for smith’s work in general” (Dickens 179). Pip looks down on his home and working conditions, eager to escape. This internal place of hatred towards his upbringing reflects his ambition and aim toward a higher place in society. The ad for farmers portrays these general working conditions for the working class, two-hundred and forty dollars a year can only get one so far, whereas compared to an average upper-class member, a character like Miss Havisham, whose wealth is recurringly acknowledged with her mansion and extravagant clothing, considerably makes far more than even three-hundred pounds a year, which is considered the average wage for a middle-class worker at the time. An advertisement like this not only brings further attention to Pip’s internal feelings regarding his social status but also provides a deeper understanding of the overall working conditions that took place when the novel itself was being released.

Ward's Perfect Fitting Shirts

As Pip prepares for his exciting trip to London towards his ‘new and improved’ life, his various preparations further reflect on class and social status. One of these factors is his clothing; this compares to the portion of the publication that advertises “Ward’s Perfect Fitting Shirts,” this brings attention to the level of detail and sophistication found in upper-class society at the time, providing ads that target perfectly fitting clothing (Harper’s 112). One specific passage in the novel that relates to this is when Mr. Trabb accompanies Pip for his fittings: “Although Mr. Trabb had my measure already…he said apologetically that it ‘wouldn’t do under existing circumstances, sir – wouldn’t do at all.’ So Mr. Trabb measured and calculated me, in the parlour, as if I were an estate and he the finest species of surveyor” (Dickens 183). Where at one point, Pip’s wardrobe was shabby and old, he is now getting fitted for a suit explicitly tailored to him. This contrast between the before and the ‘now’ displays the significance of clothing and its portrayal of status. While this shift in Pip’s ‘priorities’ has come from his newfound fortune, it also relates to the societal interest in men’s fashion: “Fashion and general-interest magazines for women were plentiful in the Victorian era. But within a highly patriarchal print culture that implicitly assumed a male audience, the notion of a magazine that consciously addressed men as men in the same way that women’s magazines addressed their readers…was revolutionary” (Shannon 88). The consistent theme of clothing and fashion in Great Expectation reflected the economic and social environment the novel was written in, not only providing a sole focus on the fashion of female characters but also focusing on the wardrobes of a character like Pip, and the changes he faced as he progressed his expectations.

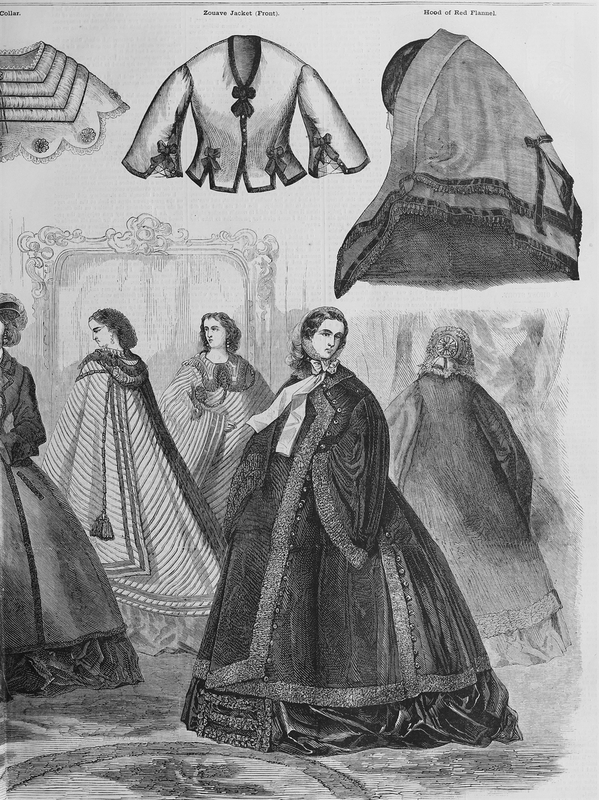

Paris Fashion

While wardrobe is a significant aspect of class distinction, as seen through Pip, there is also the undeniable emphasis on Estella and Miss Havisham’s wardrobe. An article titled “Paris Fashion” touches on all the “latest winter fashion” at the time for the paper’s “lady readers” (Harper’s 103). As Pip mentions multiple times that Estella’s wardrobe is a reflection of her social status, considering that she is always adorned in the latest fashions and fabrics, this article heavily relates to her character as a whole. However, an article covering the latest fashions and trends in the season is quickly disregarded by a character like Miss Havisham, whose wealth and status are still seen in her wardrobe but through a different lens. As she is “dressed in rich materials – satins, and lace, and silks…all white…[with] bright jewels [that] sparkled on her neck and on her hands,” her wearing a wedding dress even though she has been left at the altar in it symbolizes her fixation on her past and unwillingness to move on (Dickens 92). Her dress also indicates her wealth and social status because she can afford to wear a luxurious and extravagant garment, even though it is no longer fashionable and in ‘season.’ Even though it costs a fortune, her desire and ability to wear whatever she wants further emphasize her upper-class status much more than if she were to keep up with the latest trends. This chapter did not directly acknowledge Miss Havisham’s clothing, yet focused on her fortune. When Pip calls Miss Havisham his “fairy godmother… [and left her] standing in the midst of the dimly lighted room beside the rotten bride-cake that was hidden in cobwebs,” it provides a sense of ‘higher being’ to Miss Havisham (Dickens 189). Not only does the rotting bride cake create a parallel similar to how her wedding gown displays her wealth and status, but also the referral to her as a fairy godmother, putting her on a pedestal in Pip’s eyes, a sort of saviour whom he believes saved him from his rough and rugged home life.

Some of the most common articles and advertisements within this publication circulate the significance of appearances, which compares to the general actions of Pip in this chapter and how he goes around practically getting a ‘makeover.’ Advertisements that target “Premature Loss of the Hair” and “Chapped Hands and Lips” all fall under the fixation of beauty standards for both men and women (Harper’s 111). This connects to this nineteenth chapter of Great Expectations when Pip notices that Sarah Pocket “could not get over [Pip’s] appearance, and was in the last degree confounded” (Dickens 189). This emphasis on the drastic change in Pip’s appearance further emphasizes the difference money and status can make on a person. While flaws such as hair loss and chapped hands or lips were not necessarily pointed out on Pip himself, only one from a middle to upper-class status could afford such luxurious items to enhance or repair physical appearances. In contrast, someone from the lower class, as Pip once was, could hardly consider investing money into products like that. As “men’s interest in fashion and personal appearance, [and] their vigorous efforts to keep up with current fashions while conveying the proper sartorial image of middle-class reserve, could be justified to ensure male professional success,” the significance of appearances at this point in the Victorian era transition into relevance within a professional setting (Shannon 37). Shannon’s statement here displays the correlation between accomplishment and physical appearances; Pip’s tailored and ‘proper’ look fits his upcoming journey towards his great expectations. Advertisements that target hair growth or chapped skin reveal the societal aim of maintaining and reaching beauty standards that specifically target or cater towards specific class systems, deeming inaccessible and disregardful towards those who cannot afford such products.

This twelfth part of the serialized publication on Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations heavily focuses on men's and women’s fashion, with articles and advertisements catering to polished and tailored appearances. These items specifically reflect societal expectations, revealing the contrasting differences between the upper and lower classes at the time. Shannon’s discussion of male fashion and its evolution within the Victorian era explores the parallel between a put-together appearance and success, which are ultimately seen through the advertisements surrounding this publication and the events occurring in this twelfth portion of Great Expectations. The surrounding articles and advertisements explored in this publication greatly reflect on the occurrences and plot within the story itself, creating a perfect parallel that connects the magazine to its readers.

Works Cited

"Chapped Hands and Lips" Harper's Weekly, vol. 5, Issue 216. EBSCOhost. https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=h9k&AN=66675878&site=ehost-live&kw=true&acc=false&lpId=divl25&ppId=divp15&twPV=&xOff=0&yOff=464&zm=2&fs=&rot=0&docMapOpen=true&pageMapOpen=true

Dickens, Charles, and Graham Law. Great Expectations. Broadview, 1998.

"Harper's Weekly and Working Farmer." Harper's Weekly, vol. 5, Issue 216. EBSCOhost. https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=h9k&AN=66675883&site=ehost-live&kw=true&acc=false&lpId=divl32&ppId=divp16&twPV=&xOff=0&yOff=0&zm=1&fs=&rot=0&docMapOpen=true&pageMapOpen=true

"Paris Fashion." Harper's Weekly, vol. 5, Issue 216. EBSCOhost. https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=h9k&AN=66675882&site=ehost-live

"Premature Loss of the Hair." Harper's Weekly, vol. 5, Issue 216. EBSCOhost. https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=h9k&AN=66675878&site=ehost-live&kw=true&acc=false&lpId=divl25&ppId=divp15&twPV=&xOff=0&yOff=0&zm=fit&fs=&rot=0&docMapOpen=true&pageMapOpen=true

Shannon, Brent Alan. The Cut of His Coat : Men, Dress, and Consumer Culture in Britain, 1860-1914. Ohio University Press, 2006.

"Ward's Perfect Fitting Shirts." Harper's Weekly, vol. 5, Issue 216. EBSCOhost. https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=h9k&AN=66675870&site=ehost-live&kw=true&acc=false&lpId=divl32&ppId=divp16&twPV=&xOff=0&yOff=0&zm=fit&fs=&rot=0&docMapOpen=true&pageMapOpen=true