Part 15

Education in the Victorian era was just beginning to become accessible to those beyond the upper class and was on the precipice of becoming available to the masses, but it was not quite there yet. According to Elisabete Mendes Silva in her article, John Stuart Mill on Education and Progress, “Mill believed education was key to the progress of people’s minds and, consequently, to the progress of the country” (Silva). Applying Silva’s research regarding education during the Victorian era, it is clear of its importance, not only in England, but also in many countries around the world. This project will specifically look at the influence of the expansion of education in England and the United States of America. This will be observed through looking at two magazines that published Charles Dickens’ novel Great Expectations. The first magazine, All the Year Round, comes from England and was founded and owned by Charles Dickens. The second magazine, entitled Harper’s Weekly, comes from the United States. I will be focusing on chapters four and five of the second part of Great Expectations as it is found in the Broadview version of the novel, and using images, articles, and advertisements found surrounding these chapters in both of these magazines to examine the effect and views of education on these two countries. The interpretation of education in the Victorian era was heavily influenced by the country in which it was practiced, with educational opportunities and structures varying significantly between countries and even between regions.

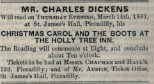

Mr. Charles Dickens Reading Advertisement

In All The Year Round, there is an advertisement for a reading by Charles Dickens at Christmas time. This is reflective of the ideas in the article, John Stuart Mill on Education and Progress, in which there is a “wake-up call for the need to educate not only the poor, but also lower middle-class people, and to revise the role of the state in popular, state-funded education, but also public education” (Silva). With the expansion of education and literacy during the Victorian era, the appreciation for literature such as Great Expectations increased among the population. However, as the quote from Silva says, not everyone was literate yet. Having Charles Dickens read his own publications granted accessibility to literature to the general public, extending to those who couldn’t read his works on their own. Pip experiences the desire to rise from poverty to the status of an educated gentleman through the entirety of the novel, Great Expectations, and in these chapters he has reached the point of receiving an education in order to complete his quest. He discusses his goals with Mr. Pocket, who he deems to “[know] more of [his] intended career than [he] knew [himself]” (Dickens 227). Without Mr. Pocket enabling Pip to receive an education, he would not have been granted the opportunity. The same applies for the reading provided by Charles Dickens: it enabled those who might not have the chance to read his work, due to poverty or illiteracy, to experience his writing.

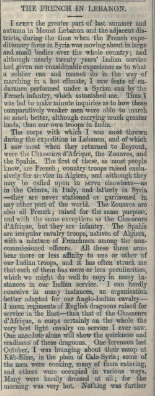

The French in Lebanon

In All the Year Round, there is an article entitled The French in Lebanon, which details the experiences of a man traveling with the French infantry. In this article, the author compares the French soldiers to Indian soldiers in their ability to endure the trials that come with being a soldier. For instance, managing the burden of travelling long distances in the heat of the sun. Without the author publishing this article in All the Year Round, their perspective on the comparison between these two infantries would have never been made. This is similar to a theme introduced in the article John Stuart Mill on Education, regarding ignorance and popular education, in which Silva states “that popular education is “one of the key answers to fight the ignorance of the bulk of the population” (Silva). By “popular education” Silva implies that people should be educated not only in the core subjects of secondary school, such as math and reading, but also be educated on events happening around the world, in order to ensure that individuals can develop a broad perspective that does not only include domestic affairs, but also foreign one of global consequence. In Great Expectations, Pip desires an opportunity to gain a wider perspective in order to enhance his future. He declares, “I should be well enough educated for my destiny if I could ‘hold my own’ with the average of young men in prosperous circumstances'' (Dickens 227). Pip has gained an understanding of the need for well-rounded education, as John Stuart Mill advocates. Viewing this chapter of Great Expectations alongside the article about global perspectives helps to create a connection for the reader that they should also seek the same complete education that Pip does.

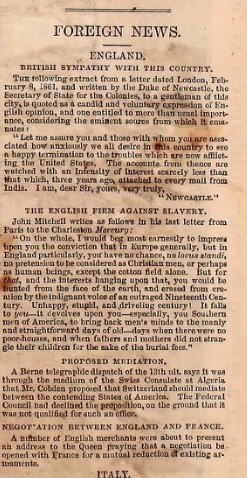

Foreign News: England

Silva states that “popular education also represented one of the key answers to fight the ignorance of the bulk of the population, instructing them so that they could cultivate their inner self as well as soothing their manners in a time full of contrasts, hypocrisy, doubts, and expectations towards the future” (Silva). The American magazine in which Great Expectations was serially published, Harper’s Weekly, had a section entitled Foreign News, which provided an account of the affairs happening in England. The first section of this segment was entitled, British Sympathy with this Country, which relates to the relationship between Pip, Mr. Jaggers and Mr. Pocket. In this chapter, Mr. Jaggers is a successful man and he acts as the harsh reality of the real world to Pip when he says “Mr. Jaggers [said] that I was not designed for any profession” (Dickens 227). Mr. Pocket wants to help Pip, and spends long conversations advising Pip on how to start his life as a gentleman. The union that forms between Mr. Jaggers, Mr. Pocket and Pip is based on the sympathy he holds for Pip. A parallel can be drawn between the article in the magazine and the relationship between the men. The description that Pip provides for Mr. Jaggers can be likened to England, as he holds the same characteristics that Silva uses to describe Victorian England when she says “reform, free-trade, individualism, economic self-regulation, self-help, and self-development permeated every aspect of Victorian life” (Silva). In both Mr. Jaggers’ and Mr. Pocket’s relationship with Pip, they represent England, whereas Pip is akin to the United States. In the article in Harper’s Weekly, there is a letter that is written from England to the United States which says “let me assure you and those with whom you are associated how anxiously we all desire in this country to see a happy termination to the troubles which are now afflicting the United States” (151). Mr. Jaggers and Mr. Pocket, more specifically Mr. Pocket, feel this way about Pip, hoping that they can relieve him of any troubles and guide him to success.

Portrait of Miss Patterson

Miss Patterson is an interesting woman. As of 1861, when this issue of Harper’s Weekly was published, Miss Patterson was “prosecuting a suit in the French Courts for the recognition of her marriage with Jerome Bonaparte” (148). Miss Patterson is portrayed in this article as a woman who holds some power, in the sense that she is able to pursue her issues legally, which was uncommon for women in the Victorian era. Although, from this article it seems she was unsuccessful in her court case, as she “broken-hearted, and with her son, returned to Baltimore, where she has lived quietly ever since” (148). In comparison to Mrs. Pocket in Great Expectations, it is apparent that they have been raised very differently and yet they both end up in similar situations. Mrs. Pocket is “guarded from the acquisition of plebeian domestic knowledge” (Dickens 220) and this results in Mrs. Pocket “grow[ing] up highly ornamental, but perfectly helpless and useless” (Dickens 220). It seems that Miss Patterson is a woman who has achieved a level of education, as is able to apply herself in a legal battle against her husband. In Silva’s article John Stuart Mill on Education and Progress, she states that “education should then be highly regarded as a means to the improvement of children and women” (Silva). Great Expectations, however, does not portray Mrs. Pocket as being educated, and so the importance of having Miss Patterson’s portrait compared against these next few chapters is so that women reading this when it was published would understand the need for education, and would have an example of how it can positively impact their lives. Despite the difference in education between Miss Patterson and Mrs. Pocket, they experience similar fates. As quoted previously, Miss Patterson ultimately lives in silence while raising her son. Mrs. Pocket only has power in one aspect of her life: over her children, as seen on page 224 of Great Expectations when she has a dispute with Mr. Pocket over how she manages her children. It is significant that the domestic and foreign affairs sections follow these two chapters, as it allows female readers to escape the pathway that Mrs. Pocket has taken in her life, and allows for them to learn about the world outside of their home, unlike Mrs. Pocket.

When examining the interpretation of education in Great Expectations, and comparing it to the data found in both All the Year Round and Harper’s Weekly, it is apparent that both the United States and England hold a positive view of education, and that both support its pursuit. Silva articulates that “education, or some educational activity, was believed to be the cure for social problems so that society could enjoy the happiness of a “sober, industrious” (Wardle 23) and morally established life” (Silva) and this is evident in the opinions of both of the magazines. Dickens' portrayal of the desire for an education by his character, Pip, is reflective of the attitude of Victorian era countries toward the importance of education. Education during the Victorian era was interpreted differently depending on the nation in which it was practiced, with educational opportunities and frameworks differing greatly between nations and even within areas, but ultimately, the “growing awareness in the need to educate the masses” (Silva) was understood and acted on in both the United States of America and in England.

Works Cited:

Bonner, John, et al. “Harper's Weekly.” Internet Archive, New York: Harper & Brothers, 1857, https://archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv5bonn/page/148/mode/2up.

Dickens, Charles. “All The Year Round.” Internet Archive, MSN, 28 Nov. 2007, https://archive.org/details/allyearround04charrich/page/504/mode/2up.

Dickens, Charles. “Great Expectations.” Broadview Literary Texts, Graham Law and Adrian J. Pinnington, 1998.

Silva, Elisabete M. “John Stuart Mill on Education and Progress.” Anglo Saxonica, vol. 19, no. 1, 2021, https://revista-anglo-saxonica.org/articles/10.5334/as.44