Part 16

Critics are divided on how to interpret the dichotomy between Wemmick and Jaggers in Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations; while some opt for finding the similarities between the men others interpret them as opposed. Monica Feinberg Cohen, a professor of literature at Columbia University, argues that the men are ultimately both striving for an ideal home; however, she sees the novel as a critique of the idea that the home can be separated from family life. While the novel certainly adds a satirical element to the separation of public and private spheres, the contrast between Wemmick and Jaggers simultaneously compares the benefits and drawbacks of fully detaching oneself from work and home— like Jaggers— or splitting oneself into two separate selves between the two like Wemmick. However, although "Wemmick is understood, not as a person whose distinctness exists prior to his socialized personality, but as a family man or a law clerk,” (Cohen) he can commit more fully to both roles while Jaggers’s calculated demeanour keeps him detached from passion as a whole. Consequently, while both men chase a grand ideal— Jaggers for conceptual aesthetics and Wemmick for simplicity— the novel raises the question of whether it is better to commit at the cost of consistency or to opt for a respectable facade at the cost of real passion, effectively placing ritualistic cultural practices as a means to grandiosity.

Concerning Dining

The sense of grandeur that the men are trying to capture is echoed clearly in the poem “The Statues,” which was published along chapters XXV and XXVI of Great Expectations on March 16, 1861. The poem describes a grand Abbey but there is a sense of sadness and true meaning accompanying the grand imagery of the “vast canopies”, and beautiful images of “torchless Angels” and the three statues themselves. The poem reinforces the idea that if “great deeds are living spirits; [and] the great dead find sepulchre in earth and oceans round,” (ATYR 541) one’s place of rest will match the grandeur of their life. The poem finishes by answering the question of what makes greatness: love. It is no coincidence this poem is in the same issue, it seemingly highlights that both men are striving to achieve greatness through their love or dedication to either meaningful action or conceptual nobility.

Wemmick’s dinner in particular is reminiscent of the poem's combination of rest and grand aspirations. Wemmick’s personality, and presentation of his home very much raise an effort to embellish the nobility of keeping his home separate from serious business; he seeks nobility and pleasure and glory of a warmer sort than that he can achieve through his professional practice. Despite that it “was the smallest house [Pip] ever saw the firing up the canyon invokes military greatness and noble sacrifice, his spread of food welcomes community and love, perceiving his house itself as a castle highlights the personal significance of grandeur and comfort. By making his house, feel like a palace he can convince himself that he is that statue of the “mailed but casqueless night plated an armor, dimly red with gold.” (ATYR 241)

On the other hand, Jaggers seeks distinction in a more abstract sense, instead of exuberant displays that highlight his values, he uses his understanding of the world to separate himself from his guests and, by extension, the general population. He has no use for grand frivolity when he can adorn himself with humility, preservation and intellectualism by controlling the people around him. Instead of using material displays to highlight his sense of personal importance, his opinions serve as a reminder of his own worthiness of a reward, or praise; he presents his opinion of Drummle, for example, as completely enigmatic to innocents like Pip, who cannot fully appreciate the grandeur or interest of his character. Jaggers places no importance on his moral judgement of Drummle because appreciating his impact— and sharing it— is more important to him than real emotional reflection or connection to others. In other words, his appreciation of the big picture of the universe is both grand in itself and serves as an accessory to Jaggers’ sense of self-importance.

Statues

The sense of grandeur that the men are trying to capture is very clear in the poem “the statues ” which was published along the chapters of great expectation of analyzing and March 16, 1861. no, the poem Chronicles, an epic story of a maiden who dies, and the grandeur that comes along with it, the story encompasses that search for grandeur that both men are trying to do. The poem speaks of grand imagery like “vast canopies”, and beautiful images of “arched necks”, and “torchless Angels” however, those are also accompanied by a sense of peace and calm. Wemmick’s dinner in particular is reminiscent of this combination of domestic peace and grand aspirations. His house very much feels like home to Pip almost immediately, he feels at ease there QUOTE and it almost reminds him of the sense of nostalgia that he felt in his hometown. However, Wemmick’s personality, and presentation of his home very much raise an effort to capture that sense of grandeur that is present in so much Victorian literature; he seeks nobility and pleasure and glory in very different ways. The firing up the canyon invokes military greatness, his spread of food indicates a search for grandeur, and is depiction of his house is a castle highlights his value of status. By making his house, feel like a palace he can convince himself that he is that “mailed but casqueless night plated an armor, dimly red with gold.” similar to the night he can paint himself with all of the trappings and entertain others, as if he was wealthy, but he doesn’t have the protection that status would come with.

On the other hand, Jagger seems to invoke the poem sentiment that truly great people will be loved by God as they are due to their power and affect over other people. The maiden lays dad, but she “pleaseth God who careth her own way.” the passage of Oaks, the Bible passage of judges 14:3 in which Samson says to his father to “get [his wife] for [him], for she pleaseth [him] well.” in that passage there is this notion that being a certain good of character or possessing a certain quality will make you want it I will and will bring your glory weather like being a husband or riches, or even just a lovely place to rest, filled with statues and grand architecture. And that way, Jaggers seeks to control the way other people perceive him while boasting his appreciation for truth and genuine character. He evokes that same sense of grandeur that Wemmick does, but he places himself in control of it. Instead of impressing his guests, with exuberant spreads of meat and bread, he presents delectable meals one at a time on his command. Even his choice of servants highlights, his own moral propensity, and his appreciation for truth, and having that be enough to evoke grandeur. Molly is housekeeper, and only servant, reminds him of his ability to do good things he helps her hide her child, and now gives her housing in the job, even despite her criminal status.(QUOTE) while she serves as a reminder of his own worthiness of a reward, or praise, she also serves as a symbol for what can happen if you were a person of strong solid character. He praises her for her strong hands, which serves as a direct standing for her story and experiences, and uses it as credit for the degree of entitlement that she has to all good things.

The Wonders of the Sea

The food choices also make a big difference in the perception of the men’s dinners. In All the Year Round January 5th 1861 edition, there is an article about “The Wonders of the Sea,” which discusses underwater life, and societal perceptions of it. In it, he acknowledges that “the sea is highly important as a never-failing source of food to the human race; but a few facts in the history of a race, or more extraordinary than the prejudice which permits enormous quantities of this valuable food, to be wasted and neglected, where it is most plentiful.” (ATYR 296) in that way, while eating fish was relatively common, the explanatory tone of the article implies a stigma around fish and its nutritional value. As Jaggers serves fish, alongside meat that was more common in England during the Victorian era, shrouds Jaggers’ dinner in an air of mystery and exoticness. The sea and both the exploration and exploitation of its resources remained largely mysterious and oftentimes was up to speculation, the article even has to state that “there is no reliable evidence of the existence, in the ocean of a gigantic reptile, resembling a serpent.” (ATYR 295)

Jaggers’ choice of food exacerbates his feeling of intellectual superiority and the consequent detachment from other characters. His willingness to eat fish suggests that he is well-read and is aware of new information concerning seafood and the value of fish in general. The article also mentions that “the lower classes in Ireland wooden many cases, rather starve than eat the fish with which their shores abound,” (ATYR 296) implying that Irish people are ignorant and wasteful for not eating fish. In that way, by serving fish, Jaggers seems to be placing himself above others through his appreciation for knowledge; he emphasizes the importance of appreciating objective and consistent logic. Additionally, by serving fish and expecting others to eat it too, he sees this consistent detachment from the expectations of others— whether it be in serving method to the type of food— as a type of control over others; as his ideal of grandiosity is intellectualism and abstract appreciation, he expects others to follow his example and be intimidated to the point where he feels save even though he “never lets a door or window be fastened at night.” (Dickens, 235)

Chinamen's Dinners

Of course, Wemmick is also strategic about his choice of food. While Jaggers places himself on an intellectual pedestal above his guests and general rhetoric, Wemmick highlights his food’s association with English culture. Wemmick’s eccentric and polarized character seemingly separates him from normalcy, however, his food and emphasis on conventional measures of status— military prowess, mannerly expectations and exuberant spreads— suggest the opposite: a connection to Victorian England’s culture. In the article “Chinamen’s Dinners,” the writer makes it clear that the British conceptualized their basic cuisine as proper and hearty. The English diet commonly included Wemmick’s selection of mutton, pork and bread which the author contrasts with the popularity of rice; which is written about as bland and flavourless, having “very little additions in the way of ‘relish’ a few vegetables, or at most a little bit of fish to help it down.” (ATYR 355) While the author goes on to embellish Chinese cuisine’s emphasis on rich flavour, the only distinction made between the basic Chinese and English ingredients is essentially the overall quality of the ingredients; while Chinese food can be delicious, it is due to the exotic talent and vision of “the hardy Chinaman,” as to where British food is generally good despite “the native cook in a European family […] [making] occasional mistakes such as boiling a salad, or serving up green peas in pods.” (ATYR 356) In that way, Wemmick’s cuisine is emblematic of the British attitude surrounding food and highlights his dedication to conventional grandeur in a way that enables him to connect with others in a much more personal way than Jaggers could: by enthusiastically participating in British culture and lowering himself from his role as a lawyer to play that of a gracious host.

A Legend of the Aryan Race

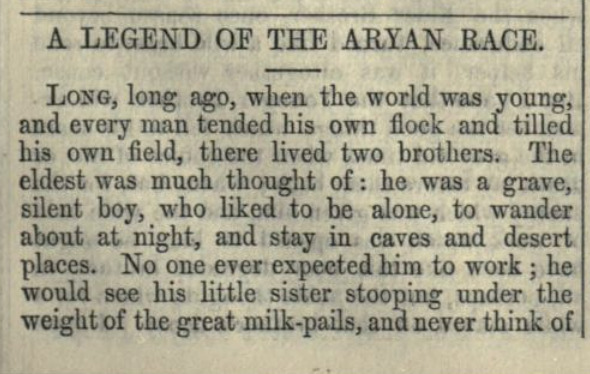

The story “A Legend of the Aryan Race,” published in the All the Year Round on December 6, 1860, reinforces the idea of Wemmick’s seemingly frivolous and carefree demeanour has more range than Jaggers’ stoic and respectable character; based on mere personality and the dinner scenes surface function, Jaggers’ philosophy seems to be the less frivolous and noble due to his dedication to his work and abstract concepts of justice and order. However, However, in this legend, the younger brother who “was a merry active boy” is also “ever ready to help here and there and everywhere at the same time.” meanwhile, the elder brother, who “was a great and silent boy, who like to be alone to wonder about at night and stay in caves in desert places” (ATYR 212) has no expectations placed upon him and is therefore detached from people around him. Like Wemmick, the younger brother uses work, frivolity, and adventure to avoid thinking, but because he is useful and brave and bright, people respect him anyways.

The older brother, in his thinking and romanticism about the world, actually ends up missing out on real experiences and connection; essentially cheating himself out of the general respect of others and placing himself as an objective observer, just like Jaggers. The younger brother eventually tells the elder brother that “ those magnificent imaginings of [his], those deep thoughts, grasping sometimes at truth, but often are bright and flimsy has a phone bubble— could [he] not read in them the great lesson of unceasing toil which you have striven against in vain?” (ATYR 212) Like Jaggers, the older brother misses the out on the very thing he was striving for; in using Molly, his handkerchief, and control of the food as a credit to his character, he ironically prevents himself from acquiring a distinct, respectable character of his own. He hides behind his grand logic and arguments but is unable to stand for anything beyond what his clients need; even his kind deed towards Molly is a direct result of the requests of his client, Miss Havisham.

While the average modern reader, such as Cohen, perhaps opt for devaluing the brilliance of Wemmick’s extreme separation of his duties while painting Jaggers’ consistent demeanour as a vain attempt to find a home or comfort, these articles from the All the Year Round complicate the connotations of the men’s behaviour. While Wemmick seems to be frivolous and extravagant, his choices in food and entertainment in chapter XXV are more reminiscent of comfort and familiarity, so his separation of personality seems to be more of an attempt to keep his life uncomplicated and as carefree as possible. On the other hand, Jaggers’ detached high-brow meal in chapter XXVI and his tokenization of Molly’s struggle represent a detachment from both simple comfort and real human connection; he’d rather see both as cold logical procedures than strike a balance between his work and home. Therefore, although Wemmick’s split personality does come with its own drawbacks, his ability to passionately commit to both his family life and his career should not be underestimated as a schism or an inability to face the facts that Jaggers lives with.

Works Cited.

"A Legend of the Aryan Race." All the Year Round , vol. IV, no. 85, 8 December 1860, pp. 211-213. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/allyearround04charrich/page/211/mode/1up

"Chinamen's Dinners.” All the Year Round , vol. IV, no. 91, 19 January 1861, pp. 355-356. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/allyearround04charrich/page/355/mode/1up

"Concerning Dining.” All the Year Round , vol. IV, no. 96, 23 February 1861, pp. 465-468. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/allyearround04charrich/page/465/mode/1up

“Dickens I: Great Expectations and Vocational Domesticity.” Professional Domesticity in the Victorian Novel: Women, Work and Home, by Monica Feinberg Cohen, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1998, pp. 70–99. Cambridge Studies in Nineteenth-Century Literature and Culture.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. Edited by Graham Law and Adrian J Pinnington, Broadview, 1998.

"Statues" All the Year Round, vol. IV, no. 99, 16 March 1861, pp. 541. Internet Archive.https://archive.org/details/allyearround04charrich/page/541/mode/1up

"Wonders of the Sea.” All the Year Round , vol. IV, no. 89, 5 January 1861, pp. 294-299. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/allyearround04charrich/page/294/mode/1up