Part 18

On March 30th, 1861, Harper’s Weekly printed a new chapter of Great Expectations as part of Charles Dickens' serial publication in America. The chapter was released a week before the British journal All Year Around without the final changes within the chapter. The American journal contains several different articles, ranging from political heroes to short stories, that all correlate to our interpretation of the newly posted chapter. Therefore, we will be looking at a few specific articles that were posted within the same issue, analyzing how each item intricately foreshadows the upcoming chapters of Great Expectations. Also, the articles help us understand the characterization of Pip and his struggle to conform to his own identity by revealing the capitalist structure of Victorian society. In return, the articles presented in Harper’s Weekly highlight the significance of Chapter XXVIII and how it leads up to the climax of the novel.

Is it a Joke, Or is it Victorian Society?

April Fool's Day was the first article published in Harper's Weekly on March 30, 1861. The cover features citizens "enjoying the usual frolics of the day" (Harper & Brothers 194) as the holiday celebrates a "number of tricks and hard practical jokes played upon unsophisticated persons" (Harper & Brothers 194). While these jokes can be fun for children, many of these pranks can result in serious consequences. It is interesting to find the first article talking about being fooled by jokes, as Chapter XXVIII of Great Expectations reveals the future for Pip. The many foreshadowing moments in the chapter allude to the serious consequences that Pip will endure in future chapters. The article serves as an allusion to Pip and how he plays into the hands of Miss. Havisham and her plan for revenge. This is shown through the representation of the Satis house and its influence on Pip.

It is without a doubt that the Satis house serves as an enchantment for Pip. The house often represents Pip’s desire to climb the social ladder, including his love for Estella. Because Pip started his journey to become a gentleman at the Satis house, it is only natural that he chooses to believe that Miss. Havisham was the sponsor who sent him to London. As a result, Pip begins to believe that the stars have aligned for him when it comes to his social standing. This is seen through his journey back to the countryside, where he contemplates his own delusions about his future with the two women. Pip concludes that since Miss. Havisham adopted both Estella and Pip, it is obvious that she intended to bring the two together. He goes so far as to say that he does "all the shining deeds of the young Knight, and marr[ies] the Princess" (Dickens 261). It is interesting to note that Pip’s thoughts compared to his younger self seem more confident than ever. As we read his undying confession of his love for Estella, he is more assured of himself than ever due to his newly found wealth.

In Victorian society, wealth means everything, including one’s placement on the social ladder. As seen with Mr. Jaggers, he is nothing more than a businessman without thinking of others' situations. His emotionless decisions give him an advantage in society, as he picks and chooses clients based on how much money they have. Therefore, characters like Mr. Jaggers represent the pathological effects of capitalist restlessness and the constant climb of the societal ladder. In many cases, Great Expectations critiques the class structure in Victorian culture as it "fetishsize[s] fascinating appearances and "epiphanic moments" at the expense of quiet necessities such as human empathy and duration through time" (Grass 79). This is particularly key to Pip, as he does not understand the consequences of climbing the societal ladder through the romanization of Estella and the lavish lifestyle that Miss. Havisham offers; therefore, he plays straight into the hands of the structure of society. Furthermore, since he believes that Miss. Havisham is his patroness, he is being fooled and played by the woman herself, which results in Pip’s future downfall. As a result, Pip is part of a big practical joke embedded deeply in Victorian society, which Miss. Havisham cleverly manipulated in her grand scheme

The Ghost of the Past: A Play with Foreshadow

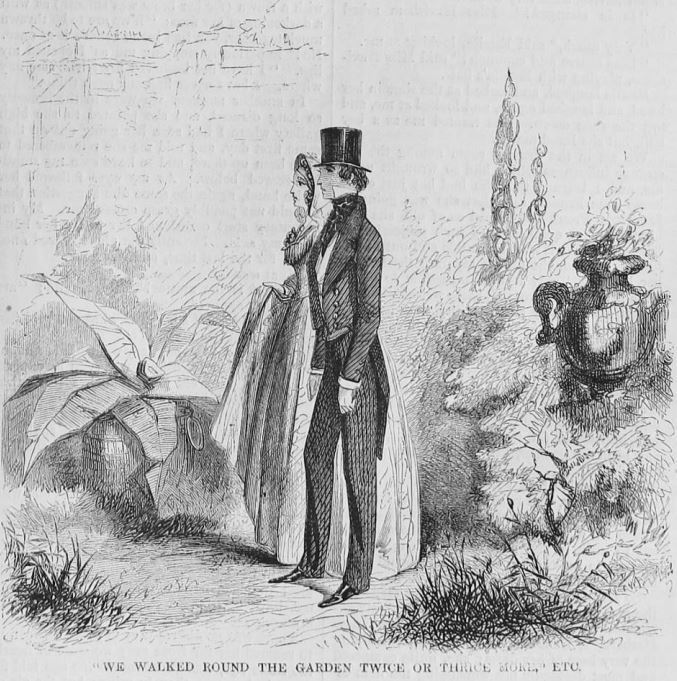

Chapter XXVIII serves as a major foreshadow of what happens to the future Pip and Estella. The ghost of Estella’s past haunts both characters in the present and the future. The chosen illustration of the walk in the garden serves as a major hint to the climax of the story. In both Estella and Pip’s serious faces, we can conclude that the conversation the two share is a serious foreshadow in two ways: Pip’s downfall in the future and Estella’s characterization. Firstly, what is love for Estella? As hinted at in the chapter, love is something she cannot feel. She coldly remarks to Pip in the conversation, "I have no heart—if that has anything to do with my memory... I have no softness there, no– sympathy– sentiment— nonsense" (Dickens 267). This quote serves as a major foreshadowing of the future when we read Estella's point of view. The main reason she cannot love Pip is that she was never taught love; therefore, once again, she is playing into the hands of Miss. Havisham. Furthermore, she responds to emotional fury due to the allusion to her parents, Molly and Magwitch. As a result, the only reason why she let Pip kiss her on the cheek was that she witnessed the quarrel between Herbert and Pip, responding to her suppressed emotions. This, in return, reveals that Magwitch is her father, which is reflected in her expression when she discusses her notion of love with Pip. This triggers a series of events where Pip is exposed to his future as he contemplates. "What was it that was borne in upon my mind when she stood still and looked attentively at me?" (Dickens 267). The emphasis on "was" reveals to the reader that something is particularly wrong with Estella’s expression. Not only does it hint towards the future outcome of Pip’s true patron, but it also reveals Estella’s parentage.

Furthermore, the overgrown garden symbolizes the secrecy behind bushes. As well, the garden as depicted in the illustration looks quite similar to a marsh. Therefore, the meanings behind the overgrown garden point toward the ghost of Estella and Pip’s past. An encounter with gothic elements in Victorian literature serves as a development towards the climax of the novel. As a result, the choice for this illustration cleverly nods towards future events that spiral for Pip and Estella, pushing the audience to analyze the choice of illustration in context with the chapter.

Pip, it is Okay to be a Common Boy. Sincerely, Patience.

Part of Harper's Weekly includes a series of short stories created by different authors that correspond to the major themes of Great Expectations. The story of The Parson's Daughter of Oxney Colne by Anthony Trolope centres around a woman named Patience Woolsworth who lives in the countryside. Like Pip, Patience is not considered a ‘high-ranking’ member of society; however, unlike Pip, she is proud of her identity. Patience wants her future husband to accept her for who she is—a simple country girl. As she falls in love with Capt. John Broughton, the pair decide to get married until John attempts to teach Patience that the marriage would raise her social status. As seen in the conversation, Patience views the change in social standing as a dishonour to her name; therefore, she breaks off the engagement with John. Here, it is interesting to see how the characterization of Pip and Patience correlate with one another. Similarly, they both come from lower social standings in Victorian society. However, in contrast, Pip has a different mindset when it comes to identifying oneself in a cruel society. Firstly, Pip desires to be a gentleman rather than a "common" man to raise his social status. Secondly, Pip’s love for Estella is merely a chase to climb up the social ladder. This is because whenever he looks at her or converses with her, Pip slips "hopelessly back into the coarse and common boy again" (Dickens 264). He even acknowledges that Estella still treated him like a boy during their conversation with Miss. Havisham. As a result, Pip reverts to his younger self and his desire to become a proper gentleman in order to be a proper lover for Estella. This challenges the notion of identity when Pip chooses to cut off his contact with Joe for the sake of his image and reputation. Patience, on the other hand, cuts ties with John because he simply did not accept her for who she was. Therefore, there is this comparison to what Pip should be when it comes to self-confidence in society when we look at Patience’s attitude towards social standing. Is it worth cutting off Joe and Biddy for the sake of love? This brings us to our next section on Pip’s identity.

What is a Man's Character Worth, if it be not Worth Every Thing?

In 1 Corinthians 13:4-7, the bible verse teaches us that "Charity is patient, is kind… Charity does not rejoice over iniquity, but rejoices in truth" (Catholic Public Domain,1 Corinth 13:4-7). This bible verse serves as a life lesson for everyone and closely resonates with Pip’s character. What is a man’s character worth if not the truth? An article in Harper’s Weekly titled "Charity is Patient" questions the worth of a man’s character using the case study of Sir Philip Sidney. As students, we know that one of Sidney’s biggest works as a romantic poet is his sonnet "Astrophil and Stella ''. The sonnet itself appeals to the audience’s heart, making Sidney "the soul of honor, the ideal of his time" (Harper & Brothers 195), or a gentleman. As the article contemplates, how do we know that Sidney has not committed a crime or done anything mean during his lifetime? If he is a lover, as seen in his sonnets, then he is not an evil man. As a result, we do not judge his character because his sonnets speak to us through love and kindness, revealing the softness of a man’s heart.

However, as the article asks, how would we know? We would never know Sidney’s true character unless he confesses from his grave. The same can be said of any man— "why should we not distrust our own impression, our own opinion, when a friend, or any person whose life is a long hostage to honesty and justice, is exposed to calumny?" (Harper & Brothers 195). Every man is susceptible to failure. He can be at fault, or possibly an evil man. But it is how a man handles the truth of failure that defines the kindness in his heart.

Interestingly, "Charity is Patient" is posted in correlation with the release of Chapter 29. As we have discussed, Victorian society is notorious for creating gaps between class structures due to the rise of capitalism. Like Mr. Jaggers, for a man to be successful in Victorian society, he had to remove his emotions and chase money. Pip does not harbour the same emotions as Mr. Jaggers does, which differentiates him from the rest of upper-class society. Although he is a common boy, he already has the heart of a gentleman. As readers, we have an omnipresent view of Pip’s character from the beginning of the novel. His chase up the social ladder is false, as he fakes his outer appearance to fit into society. This is evident as we read Estella and Pip’s conversation in the garden. Estella asks Pip if he has changed his inner circle due to his newly found wealth. Although Pip had planned to visit Joe after his stay with Miss. Havisham, the plans changed due to Pip's worry about what others think. At the end of the chapter, we get a sense of doubt as Pip cries about the saddening situation of cutting off Joe (Dickens 273), revealing a part of him that is true to his heart. Here, we get a glimpse of Pip’s true character before he reverts to his outer appearance as a "gentleman". Therefore, the questions posed in the article serve as a foreshadow for future Pip to contemplate his own character. Pip does not know who as of this chapter; however, with the article and the story of Patience acting as a foreshadow, we know that Pip will accept his own identity when the past is revealed to him.

---

As a result, the publication of Great Expectations by Charles Dickens in Harper’s Weekly in serial numbers kept the audience on their toes with many foreshadowing elements within the chapter. In correlation, the articles and items published within the same issues act as an analysis of Pip’s character, hinting toward his fate in upcoming chapters. By analyzing Victorian society, we can conclude that the publication in Harper’s Weekly provided an important foreshadow of Pip’s identity, allowing us to contemplate our own characteristics as truthful human beings

Works Cited

Catholic Public Domain Version. YouVersion. 2023. https://www.bible.com/bible/42/1CO.13.4-7.CPDV Accessed 7 April 2023.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. Edited by Graham Law and Adrian J. Pinnington, Broadview Press, 1998.

Grass, Sean. “‘Portable Property’: Commodity and Identity in Great Expectations.” The Commodification of Identity in Victorian Narrative: Autobiography, Sensation, and the Literary Marketplace. Cambridge University Press, 2019, pp. 78–104. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108613347.003 Accessed 7 April 2023.

Image Cited

Dickens, Charles "Great Expectations: Chapter XXVIII." Harper's Weekly, vol 5. no. 222, 30 March 1861, pp. 205-206. Internet Archive, https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=h9k&AN=67218228&site=ehost-live&ppid=divp13&lpid=divl24 Accessed 7 April 2023.

Harper & Brothers. "April-Fools Day." Harper's Weekly, vol 5. no. 222, 30 March 1861, pp. 194. Internet Archive, https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=h9k&AN=67218228&site=ehost-live&ppid=divp1&lpid=divl1 Accessed 7 April 2023.

Harper & Brothers. "Charity is Patient." Harper's Weekly, vol 5. no. 222, 30 March 1861, pp. 195. Internet Archive, https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=h9k&AN=67218228&site=ehost-live&ppid=divp3&lpid=divl10 Accessed 7 April 2023.

Trollope, Anthony. "The Parson's Daughter of Oxney Colne." Harper's Weekly, vol 5. no. 222, 30 March 1861, pp. 202-204. Internet Archive, https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db= Accessed 7 April 2023.