Part 19: April 6th, 1881

Issue 223 of Harper’s Weekly draws together disparate events in Great Expectations: Mr. Trabb’s boy imitating Pip, Herbert begging Pip not to marry and the tragedy of Mr. Wopsle’s performance as Hamlet into the reader’s contemporary context. With the incitement of the American civil war days away, Great Expectations is embedded in a discussion of male homosocial bonds and how they underpin or undermine ascendency, national identity, and marriage. The critical tradition established around male intimacy in Dickens commonly searches for moments of violence, with Sedgwick describing tender male intimacy as “sesame street”—without eros (Furneaux, 35).

Recent scholars, such as Furneaux, have challenged this essentialism, making a case to legitimize “life-sustaining erotic contact between men” in sequences of nursing or bodily care between Pip and Herbert (36). She further argues these sequences represent “positive interest in exploring, and even celebrating, such 'deviant' desires” (36) and a representation of “properly sublimated, adult male homosociality” (38). Earlier in the novel, without the pretext of injury to vindicate physically intimate contact, the discussion of marriage proxies homosocial romantic ideation. Embedded in the civil war context, Herbert proposes the homosocial bond between men as a type of safety, rather than violence, in the anti-marital plea that could have served as a call to arms to the civil-war era reader to put their love of nation (and their fellow man) before marital desire and enlist.

The opposite of Marriage is Ascendency, Or: Pip and all his Doppelgängers

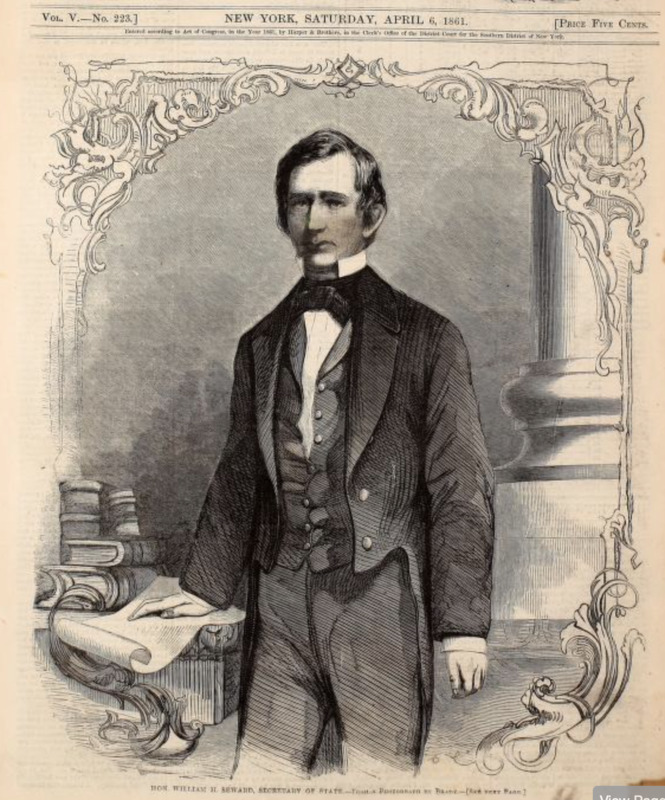

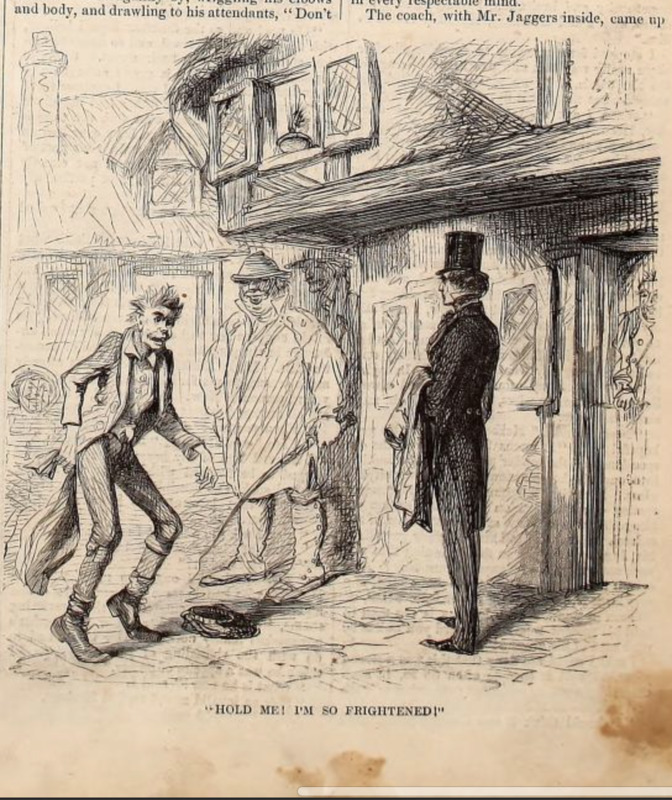

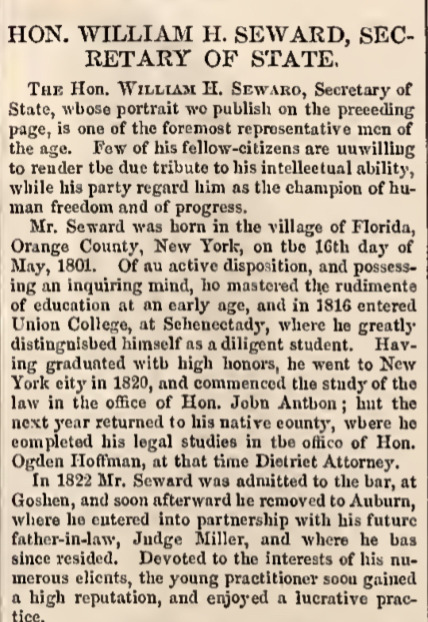

The above images of Secretary of State William H. Seward, and Pip are conspicuously similar in attire, posture, and impression. This makes Pip appear out of place in his illustration—considerably more well-rendered than the more impressionistic sketches of the other two characters. This parallel positions Pip as a parallel to Seward, whose great success and ascendency begin, like Pip’s, through his "inquiring mind,[…] greatly distinguish[ing him] as a diligent student" (210). This conveys the theme of failed imitation beyond Dickens’ dichotomies, in which Trabb’s Boy imitates Pip, Herbert imitates Pip in announcing his engagement, Mr. Wopsle imitates Hamlet, and Pip imitates some intangible ideal of a gentleman that Estella could desire. As such, Trabb’s Boy’s imitation is inexact down to his clothes: his tailcoat with lapels, with a buttoned vest underneath, cut similar to Seward’s, and relative to the third character, his trousers are more fitted. The resemblance stops, however, at the fit. Relative to the sleek lines of Pip and Seward’s clothes, his coat wrinkles around his back, his trousers cut off mid-calf, folding and wrinkling with a haphazard cuff, and one shoe is coming undone. Like his attire, his antics “pull[ing] up his shirt-collar, twin[ing] his side-hair, [sticking] an arm akimbo, and smirk[ing] extravagantly by, […] drawling to his attendants, “Don’t know yah!” (Dickens, 275) represent a satirical caricature type “expropriative” performance, in which he takes the hypocrisies of Pip’s affected gentility and mocks them by performing them to excess (Butler 957).

This troubles Pip’s performance, affecting “serene and unconscious contemplation [which] would best beseem [him]” (274) to avoid association with Mr Trabb’s boy. The imitation jeopardizes the authenticity of the original. Queer philosopher Judith Butler characterizes gender as constituted by this type of imperfect, repeated, panicked performance of a “phantasmatic heterosexualized ideal” (956); while gentleman is a more specific iteration of gender, the imposition of heterosexual desire predicated on performing gentility leaves Pip searching for responses appropriate to his role rather than authentic to his experience. His performance is troubled and incomplete because he cannot alienate Trabb’s boy enough to escape satirizing. Even without Trabb’s boy highlighting his failure, however, his performance is struggling and incomplete without Estella’s responsive desire, and he ruminates on the social sanctions for failed performance:

Miserably I went to bed after all, and miserably thought of Estella, and miserably dreamed that my expectations were all cancelled, and that I had to give my hand in marriage to Herbert’s Clara, or play Hamlet to Miss Havisham’s Ghost, before twenty thousand people, without knowing twenty words of it (Dickens 286).

Estella’s absence haunts Pip, alongside the forced presence of Herbert’s fiancée, the failed performance on stage, and the public spectacle of both his upward and downward mobility. He is haunted by marriage—the consummation of his performative role, as a spiritual successor to Miss Havisham, whose unrequited courtship left her haunting her own house. Herbert’s fiancée as an imposition upon Pip mirrors Herbert’s discomfort and disavowal of Pip’s pursuit of Estella. Herbert equally mimics Pip after Pip rejects his plea to “detach [him]self” from Estella. The imitation fails—he announces its artifice as sublimation to "make [him]self agreeable again” (279). Where previously, he dismissed engagement as “What-you-may-called-it […] Affianced […], betrothed, engaged, what’s-his-named (207), he now imitates Pip’s courtship role with his engagement. Furneaux argues this is necessary to “ostensibly sanction” (36) yet provide a proxy for “otherwise illicit” intimate contact (37). He imitates both Pip and idealized-Estella: the man who must reach his expectations to gain marital access, and the gentleman, marrying beneath his class, to remain within Pip’s access.

While Herbert queers the desire that calls him to perform heterosexuality to save his homosocial intimacy with Pip, Pip’s performance of gentility centers appealing to Estella. Seward’s public-sphere gentility and success reveals the artifice in centering desirability in gentility. Seward’s representation, which readers encounter prior to great expectations, positions him as a noble, aspirational figure who will “tend to [slavery’s] peaceful extirpation” (211) with similarly “Great” expectations to Pip’s that he has achieved. Mentions to Seward’s marital status are scant, undermining the centrality of marriage to gentility—while Seward owes some portion of his status to his Father in Law and benefactor, Judge Miller, who becomes in a sense his Miss Havisham, his “young” marriage is seldom mentioned, contrasting Pip’s insistence he “can’t help [wanting Estella]” (279).

This brings to fruition the other fear Pip alludes to in the dream sequence, public humiliation, much like when “[Trabb’s Boy’s] sufferings were hailed with the greatest joy by a knot of spectators” (275) at the loss of his expectations. He has already been humiliated in this passage, as a part of Trabb’s Boy’s spectacle, and because the reader is comparing him with another gentleman, to whom he comes up short. His attribution that Trabb’s boy is the sole target of scorn is as realistic as Mr. Wopsle’s insistence that "Claudius, King of Denmark […] is his employer, gentlemen” (286) when he discusses the heckler at Hamlet.

Not in Costume?: On performing gender

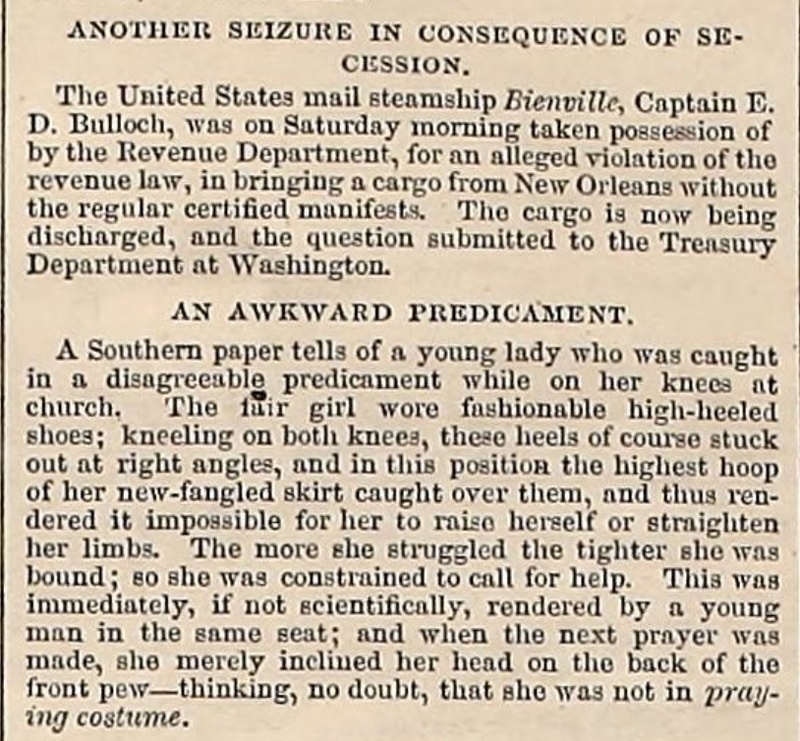

Hamlet further evokes failed performance, as “Hyperion to a satyr” (1.2.144)—Hamlet and Claudius both fail to assume the King’s role, with Wopsle-as-Hamlet failing so spectacularly that Pip and Herbert’s “pale efforts” at support lapse into “feeling keenly for him but laughing, nevertheless, ear to ear” (284). Though they laugh at Wopsle’s insistence that "Claudius, King of Denmark […] is [the heckler’s] employer, gentlemen” (286) he is as correct as Pip was to attribute all the humiliation to Trabb’s boy in their encounter. Harper’s, however, depicts another Failed performance on the Same page as Mr. Wopsle’s, in the domestic intelligence section alongside pertinent news about the brewing war. Before the personals section and after a blurb about sanctions is a description of a young woman’s attire precluding her prayers (214).

In contrast with serious political and military news, the young woman seems hyperbolically frivolous—her attire “captures” her, interfering with her performance of piety and disrupting the church experience of the man whose intercession frees her. It is equally disruptive of the “domestic intelligence” section it is placed in after news about tariffs, fortresses, words from the president, and other political news. Further, it connects to the production of Hamlet, in which Ophelia is “prey to such slow musical madness” that audience members harangue her (282) for prolonging the mediocrity of the play. When Herbert articulates that Pip’s infatuation “may lead to miserable things” (279), this article demonstrates how the frivolity of beauty can be disruptive.

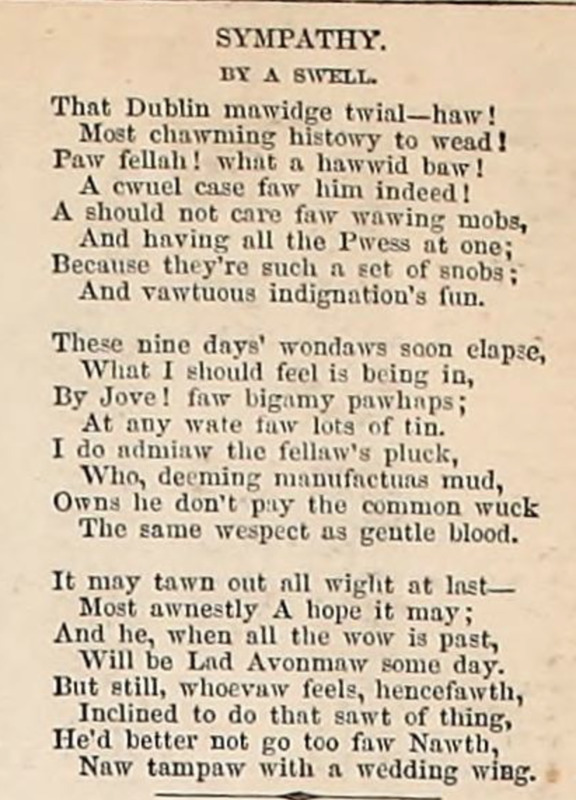

A "Cwuel case" for "wawing mobs": Satirizing marriage

Next, the poem “Sympathy” satirizes marriage for another reason—targeting a bigamy trial. The bigamist’s motives in a mocking phoneticized impersonation of a southern drawl: “he don’t pay the common wuck/the same respect as gentle blood” (15-16, 211) but warns “he’d better not go too faw Nawth,/Naw tampaw with a wedding wing” (23-24, 211). Despite the Yelverton Case being Irish, “not going too far north” evokes a moral double standard, in which the southern caricature voice can endorse “the fellaw’s pluck” (14, 211), but it’s made clear that in the North, marriage is not a tool for licentiousness. Further, it emphasizes the misery of pursuing Estella, who disdains Pip’s calloused hands, knaves, and thick boots.

If the bigamist can pervert the institution of marriage out of disdain for his wife’s non-gentle blood, what “miserable things” (279) might she do to him founded on that disdain? Indeed, in the issue one week prior, Estella establishes that even if she had respect for Pip as a person, she does not have the capacity to love him: “I have no heart […] no softness there, no—sympathy—sentiment—nonsense” (267). Unlike Yelverton, she is forthright that “[she has] never had any such thing” as tenderness (267), underscoring marriage as a danger Pip can retreat from to Herbert, for whom “it is impossible to be gentler” (428).

Now cracks a noble heart: When Marriage is War

(Hamlet, 5.2.397)

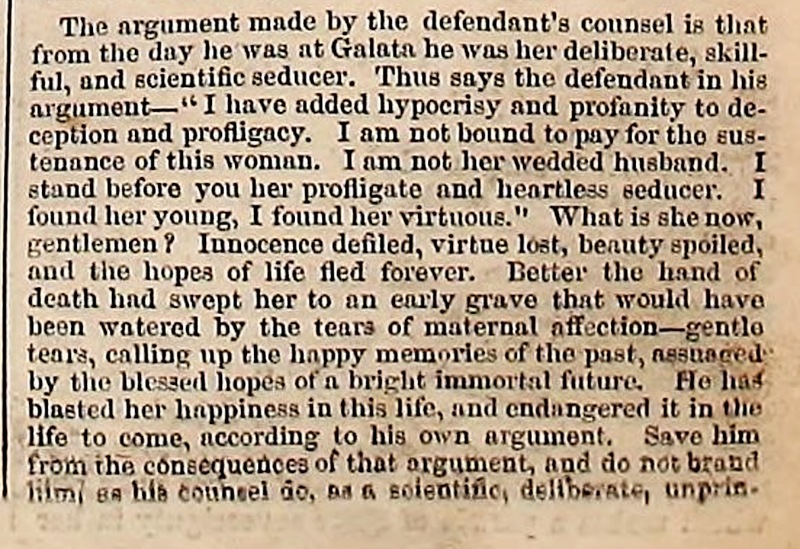

Harper’s goes into greater detail about the Yelverton Trial at the end of the issue, chronicling a man whose “love for [his first wife] was always founded in dishonour” who “[took] her from her holy work and [took] her as his mistress (221), after they met at a convent. As they were married in secret, he consummated their marriage and then absconded to marry a rich widow. His first wife, Mrs. Yelverton, possessed no defect but an excess of love for a man who did not deserve it (221-222), and the institution of marriage and the church sanctifying it could not protect her from her bigamous husband.

He enumerates the miserable things that have become of her:

“I have added hypocrisy and profanity to deception and profigacy […] I stand before you her profligate and heartless seducer. I found her young, I found her virtuous. What is she now, gentlemen? Innocence defiled, virtue lost, beauty spoiled and the hopes of life fled forever. Better the hand of death had swept her to an early grave” (221).

His remorseless and callous oration makes the consequences of the marriage even bleaker—even if she wins the trial, she cannot win a less callous husband of it. Following Estella’s warnings, Pip “should be [scared], if [he] believed what [she] said” (268) about having no heart, but it is Herbert, the perpetual idealist, struck by this fear. t Before Pip binds himself to misery, as Mrs. Yelverton has, he implores Pip, “Not being bound to her, can you not detach yourself from her?” and to “think of what [Estella] is herself” (278). His optimism falters as Pip spurns him for inevitable misery: “Now I am repulsive and you abominate me” (279), while characterizing Pip as a romantic ideal nature and circumstances have made [Pip] so romantic” (278) to suggest his capacity to partake in less harmful romantic alternatives, but proposes himself as a safe alternative to the emotional upheaval of loving Estella in the face of Yelverton’s admission that marriage to him was worse than death.

it is no more possible to dissuade Pip from Estella than to dissuade Herbert from longing to persuade him. Equal parts “restorative [and] erotically connotative,” his pleas are both to spare Pip's suffering and a “deeply intimate admission” of his longing (Furneaux 37). This scene reverses the rhythm of approach-avoidance Furneaux illustrates in Pip, “oscillating between repudiating and seeking Herbert” (Furneaux 36) Herbert intersperses his pleas “[his] dear Handel” (278) to detach from Estella with hyperbolic self-repudiation as “seriously disagreeable […]—positively repulsive” (278). Where previously Pip assured Herbert, “You won’t succeed [at repulsing him]” (278), he cannot look at him when he declines, as though it is his desire for Estella that is deviant in their homosocial context, and Herbert’s final rejection “now I am repulsive and you abominate me” (279), is the only Pip doesn’t meet with reassurance. When Pip cannot reconcile their relationship, Herbert’s sublimation: “now I’ll endeavour to make myself agreeable again!” (279) is another covert self-repudiation that masks him. It restores order between them, to convey himself as suddenly desperate for marriage like Pip, but is partner seems insubstantial, especially with the contingency: “you can’t marry, you know, while you’re looking about you” (281). Provided Herbert keeps his idealistic sights tenderly on his male companion, he can perform heterosexualized desire without being taken captive by it. In this way, Herbert’s performance allows him to remain beside Pop. As such, compassion, and love between men are positioned in the margins and between the lines of this anti-marital exposé in Issue 223.

works cited

Butler, Judith. “Imitation and Gender Insubordination" Literary Theory an Anthology. 3rd ed., edited by Julie Rivkin and Michael Ryan, Wiley Blackwell, 2017, pp. 955-962.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. Edited by Graham Law and Adrian J. Pinnington, Broadview Literary Texts, 1998, pp. 273–286.

Furneaux, Holly. “It Is Impossible to Be Gentler: The Homoerotics of Male Nursing in Dickens’s Fiction.” Critical Survey (Oxford, England), vol. 17, no. 2, 2005, pp. 34–47, https://doi.org/10.3167/001115705781004604.

“Domestic Intelligence: An Awkward Predicament.” Harper's Weekly, Vol V. No. 223, Harper and Brothers, 6 April, 1861, pp. 215. Internet Archive. Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection, Internet archives, 22 March, 2012, https://archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv5bonn/page/214/mode/2up. Accessed March 27, 2023.

“Hold Me! I'm So Frightened!” Harper's Weekly, Vol V. No. 223, Harper and Brothers, 6 April, 1861, pp. 212. Internet Archive. Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection, Internet archives, 22 March, 2012, https://archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv5bonn/page/212/mode/2up. Accessed April 1, 2023

“Hon. William H. Seward, Secretary of State.” Harper's Weekly, Vol V. No. 223, Harper and Brothers, 6 April, 1861, pp. 210. Internet Archive. Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection, Internet archives, 22 March, 2012, https://archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv5bonn/page/208/mode/2up. Accessed March 27, 2023.

“Hon. William H. Seward, Secretary of State --From a Photograph by Brady.” Harper's Weekly, Vol V. No. 223, Harper and Brothers, 6 April, 1861, pp. 208. Internet Archive. Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection, Internet archives, 22 March, 2012, https://archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv5bonn/page/208/mode/2up. Accessed April 1, 2023

“Bessie Elmore.” Harper's Weekly, Vol V. No. 223, Harper and Brothers, 6 April, 1861, pp. 218. Internet Archive. Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection, Internet archives, 22 March, 2012, https://archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv5bonn/page/218/mode/2up. Accessed April 1, 2023.

Swell, A. “Sympathy.” Harper's Weekly, Vol V. No. 223, Harper and Brothers, 6 April, 1861, pp. 211. Internet Archive. Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection, Internet archives, 22 March, 2012, https://archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv5bonn/page/210/mode/2up. Accessed April 1, 2023.

“The Great Yelverton Case.” Harper's Weekly, Vol V. No. 223, Harper and Brothers, 6 April, 1861, pp. 221-222. Internet Archive. Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection, Internet archives, 22 March, 2012, https://archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv5bonn/page/220/mode/2up. Accessed April 1, 2023.

“Virginia sketches.” Harper's Weekly, Vol V. No. 223, Harper and Brothers, 6 April, 1861, pp. 216-217. Internet Archive. Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection, Internet archives, 22 March, 2012, https://archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv5bonn/page/216/mode/2up?view=theater. Accessed April 1, 2023.