Part 20

Introduction

The April 13, 1861 edition of Harper’s Weekly was written and put to bed on the advent of the American Civil War and is therefore saturated with highly politically and socially invested content. Nestled within illustrations, poems, and dismissive paragraphs about runaway slaves and gruesome crimes, is the twentieth part of the original serialized run of Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations. The matter surrounding part twenty of the serialized Great Expectations, or Chapters XIII and XIV, infuses the content of the chapters with an additional layer of social consequence as they are entrenched in the conversation of the American civil war and matters deeply concerned with class and racial politics. The unavoidable discussion around criminality, slavery, and the Civil War in the April 13th edition of Harper’s Weekly draws attention to Dickens’s critique of the dehumanizing impacts of incarceration and class politics, as well as the way this critique informs and is informed by the contemporary issues regarding racial politics.

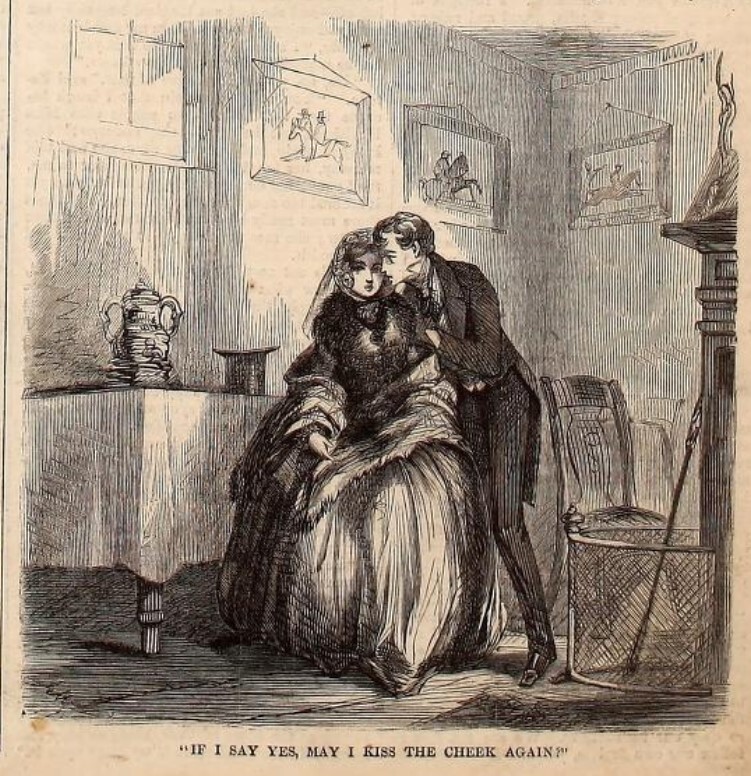

May I Kiss the Cheek Again?

John McLenan’s illustration of Pip and Estella in the carriage house in Chapter XIV visually enforces the lopsided nature of Pip and Estella’s relationship, simultaneously positioning Estella as haughty and disaffected, and Pip as suffocatingly desperate. In the illustration, Pip leans fawningly over Estella, imbuing the line he is supposedly delivering in the image with irony, as he is disingenuously telling Estella that he kisses her hand, and now her cheek, in “a spirit of contempt for the fawners and plotters” (Dickens 295). Despite his contempt for Mrs. Havisham’s scheming relatives, Pip, in this image, embodies the overfamiliar social climber. In the illustration, Pip’s almost predatory position as he looms over Estella in his pinstriped coattails reminds the reader that “Pip’s mobility . . . is tainted with the criminal and consequently rendered unviable” (Taft 353). Despite his improved financial status and surface-level signification as such, the spectre of criminality still haunts Pip, who even has Newgate, the prison he visits in Chapter XIII, “in [his] breath and on [his] clothes” (Dickens 292). Estella looks inexpressively away from Pip, her hat and “fur travelling-dress” (Dickens 292) creating a physical space between the two of them that reinforces the emotional and economic barrier between them. The sumptuousness of Estella’s untainted upper-class dress is what maintains the space between them, again reinforcing Pip’s perceived incapability of truly improving his social status due to his lower-class and criminal origins. McLenan’s illustration manipulates the reader’s understanding of Pip and Estella’s exchange in Chapter XIV as his physical positioning of the two imbues the scene with claustrophobic discomfort that highlights the artificial performativity of the scene.

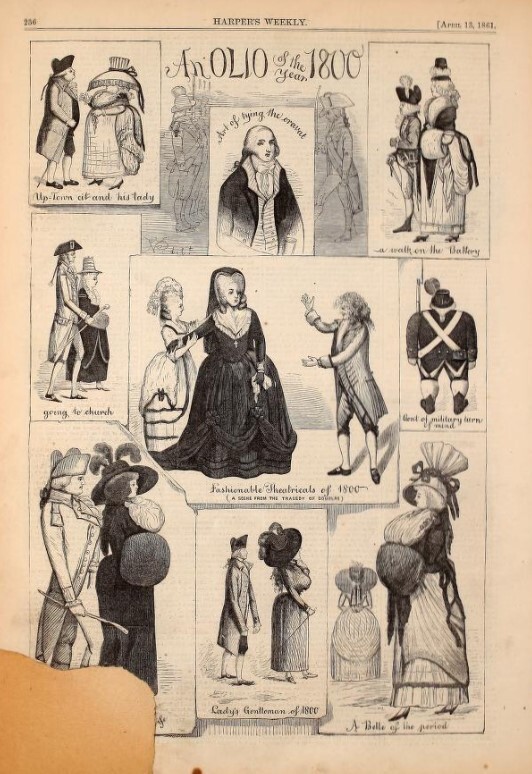

An Olio of the Year 1800

This full-page illustration, included after Chapters XIII and XIV of Great Expectations, reflects the petty upper-class domesticity of Chapter XIV and gives insight into the domestic life of upper-class Americans and the speed at which their material preoccupations shifted. The illustration sarcastically depicts wealthy Americans engaging in quotidian activities like “going to church” and on “a walk on the Battery,” enlarging the women, in their now outdated bustles, fur muffs, and enormous hats, to comical size (Harper’s Weekly 236). In Chapter XIV, Estella arrives in London “in her fur travelling-dress” seeming “more delicately beautiful than she had ever seemed yet” and Pip frets relentlessly over the state of the carriage house that he and Estella must wait in, stating that its smell, “in its strong combination of stable and soup-stock, might have led one to infer that . . . that the enterprising proprietor was boiling down the horses for the refreshment department” (Dickens 292-293). Under Estella’s upper-class scrutiny, the quotidian event of taking tea in the carriage house becomes a sort of torture to Pip. The situation of this chapter and its direct reference to styles of dress and social etiquette in the context of the ironic “An Olio of the Year 1800” accentuates Estella and Pip’s surface-level preoccupation with fleeting social rules and styles and creates an image of them as the pompous and exaggerated figures in the illustration – figures who would undoubtedly become archaic objects of ridicule less than a century later. In this light, Pip’s declaration upon his reception of Estella’s note announcing her arrival that he “should probably have ordered several suits of clothes for this occasion” (Dickens 287) becomes even more ridiculous, as his vapid materialism transforms him into one of the men in the olio, trailing behind his inflated and elaborately garbed female companion.

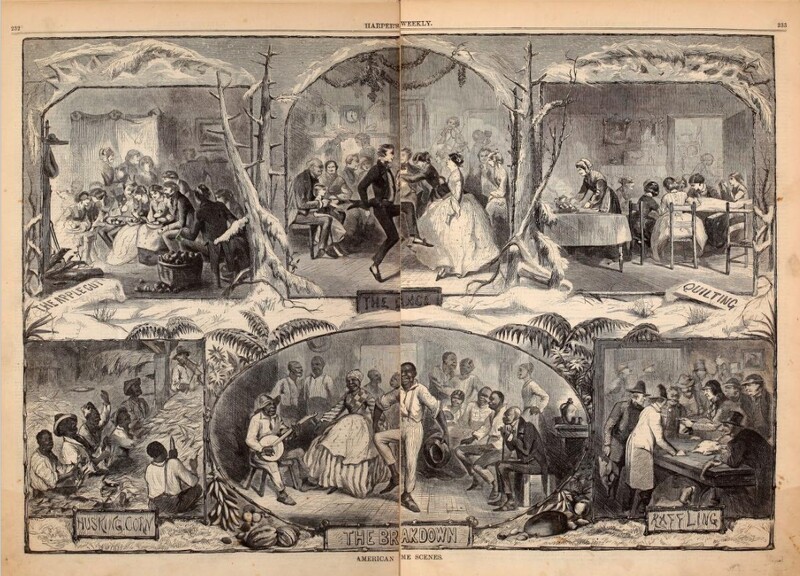

American Scenes

The two-page illustrated spread “American Scenes,” also situated after Part 20 of Great Expectations, elaborates further on middle and upper-class American domesticity and places Great Expectations in the context of race relations. Like “An Olio of the Year 1800,” this illustration highlights the quotidian aspects of American life, while also directly addressing the hierarchical relationship between black and white Americans as it literally positions the white figures in the snowy northern half of the image and the black Americans in the tropical southern half of the image. The only activity that transgresses racial boundaries in the image is that of the meat raffle occurring in the bottom right corner, in which white men are pictured raffling off various birds. This literal meat market unites the social hemispheres of the white and black Americans, creating an allusion to the buying and selling of slaves. However, despite occurring within the same social realm, the two races do not occur alongside each other in any portion of the illustration, reinforcing the fundamental social alienation and perceived inferiority and criminality of black Americans. This positioning of Chapter XIV of Great Expectations within the context of racial politics informs Pip’s instinctual disgust towards Newgate, a “frouzy, ugly, disorderly [and] depressing scene” (Dickens 289), and its inmates, whom he describes as Wemmick’s interchangeable and disposable plants (Dickens 291). To Pip, the prisoners in Newgate are a subclass of humans whose presence leaves him feeling “contaminated” (Dickens 292). Pip’s disgust at his physical proximity to the prisoners, especially as he prepares to meet Estella, recalls the social motivation for the visual segregation of “American Scenes” and prompts the reader to consider who has the authority to attribute and retract humanity. The positioning of “American Scenes” next to Chapter XIII of Great Expectations highlights the insidiousness of Pip’s early selectiveness as to who is considered truly human, as his dehumanizing disgust of Newgate’s inmates mirrors the sentiments that allowed for the proliferation of slavery and racial segregation in America.

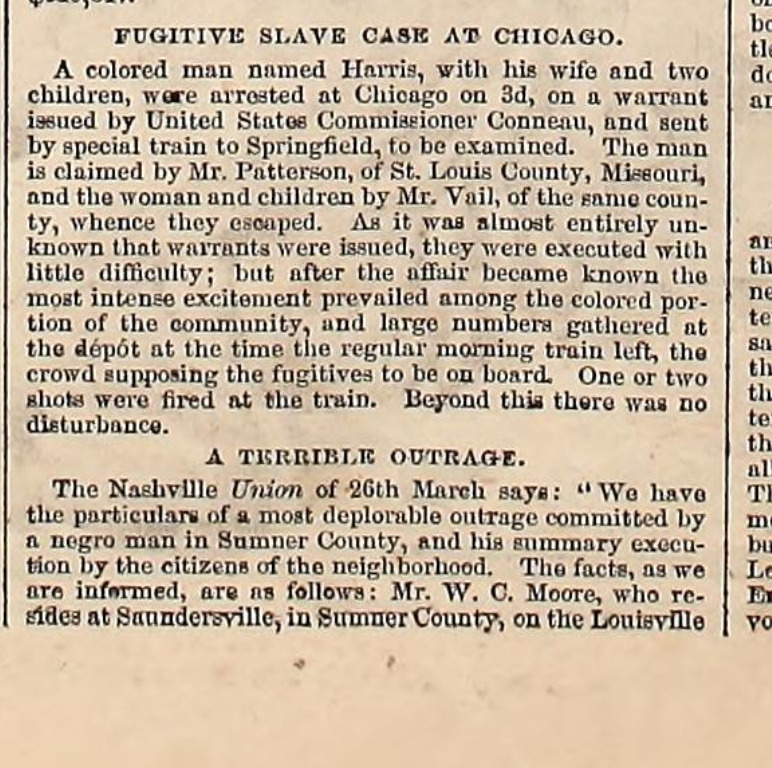

Domestic Intelligence: Fugitive Slave Case at Chicago and A Terrible Outrage.

The “Domestic Intelligence” column of the April 13, 1861 edition of Harper’s Weekly also places Chapters XII and XIV of Great Expectations in conversation with racial politics, as it includes two stories that directly relate criminality with racial identity. The first story included briefly glosses over the story of a family who has escaped from slavery being arrested and sent back to their owners, the man, Harris, to one family and his wife and children to another. The second story recounts “a most deplorable outrage” (Harper’s Weekly 231), in which a certain Mr. Moore, after purchasing a plantation and while handcuffing one of his young slaves in order to transport him to it, was attacked with a knife by the boy. Although the wounds Mr. Moore sustained were not lethal, the boy seriously wounded another man and killed Mr. Moore’s father; the boy was then shot three times and hung as punishment (Harper’s Weekly 231). The author’s treatment of these slaves as unapologetic, violent criminals, and apparent neutrality about their dire fates mirrors Pip’s unsympathetic and disgusted treatment of the inmates and Newgate, again reinforcing Dickens’s critique of the carceral system through Pip’s dehumanization of the inmates. After his excursion to Newgate, Pip contemplates “how strange it was that [he] should be encompassed by all this taint of prison and crime; that in [his] childhood out on [the] lonely marshes on a winter evening [he] should have first encountered it . . . that, it should in this new way pervade [his] fortune and advancement” (Dickens 292). While Pip is not yet aware that Magwitch is his benefactor, his contemplation of the role Magwitch, and crime in general, plays in his life is portrayed in a new light when read in tandem with the domestic affairs column. Placing Dickens’s sympathetic critique of the carceral system next to the Harper’s author’s condemnatory account of escaped and violent slaves reinforces an understanding of Great Expectations “not just as a social commentary on England’s poor but also as a tale with the runaway slave at the core of its fugitive storyline” (Elliott 44). Magwitch most obviously embodies this, but Pip’s ceaseless flight from his economic origins in pursuit of a better social position, one in which he will be awarded more humanity, also becomes a fugitive tale. The “taint of prison and crime” (Dickens 292) that Pip feels surround him from his first encounter with Magwitch is not an implication of his status as subhuman, but a condition of his social standing and a result of a stigma forced upon him in a more mild but not entirely dissimilar way to those discussed in the domestic affairs.

Conclusion

The contextualization of Chapters XIII and XIV in the April 13, 1861 edition of Harper’s Weekly exaggerates some of Dickens’s more subtle critiques of race, class, and carceral systems, as they are placed in close proximity to illustrations and columns which highlight the vapidity and cruelty of the contemporary class and racial politics. The matter surrounding Part Twenty of Great Expectations informs Pip and Estella’s relationship, as the imbalance of their relationship is depicted visually by John McLenan and they are placed in proximity to the caricatures of upper-class socialites, and the speed at which they become unfashionable, in “An Olio of the Year 1800.” The issue of criminality is also represented differently in the context of racial issues in Civil War America, as readers are prompted by content such as “American Scenes” and the “Domestic Intelligence” column to consider to whom and by which degrees humanity is granted. In this way, Dickens’s critique of the British carceral system and the dehumanization of those labelled as criminals is strengthened as well as extended to the dehumanization of black slaves in America and their assumed and unsympathetic portrayal as criminals within Harper’s Weekly.

Works Cited

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations, edited by Graham Law and Adrian J. Pinnington, Broadview, 1998.

Elliott, Clare Frances. “Writing Across Lines: Frederick Douglass, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Charles Dickens in the Black Atlantic.” Journal of Transatlantic Studies, vol. 20, no. 1, 2022, pp. 39–57, doi.org/10.1057/s42738-022-00089-2.

McLenan, John. "If I say yes, may I kiss the cheek again?" Harper's Weekly, vol. 4, no. 223, 13 April 1861, pp. 229. Internet Archive, archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv5bonn/page/229/mode/1up?view=theater.

Taft, Matthew. “The Work of Love: Great Expectations and the English Bildungsroman.” Textual Practice, vol. 34, no. 12, 2020, pp. 1969–88, doi.org/10.1080/0950236X.2020.1834700.

Unknown. "An Olio of the Year 1800." Harper's Weekly, vol. 5, no. 224, 13 April 1861, pp. 236. Internet Archive, archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv5bonn/page/236/mode/1up?view=theater.

Unknown. "Domestic Intelligence." Harper's Weekly, vol. 5, no. 224, 13 April 1861, pp. 231. Internet Archive, archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv5bonn/page/231/mode/1up?view=theater.

Unknown. "American Scenes." Harper's Weekly, vol. 5, no. 224, 13 April 1861, pp. 232-233. Internet Archive, archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv5bonn/page/232/mode/2up?view=theater.