PART 22 - A Less Pleasant And Profitable End: Portable Property And Business Ventures In Part 22 Of Dickens’ Great Expectations

INTRODUCTION

Great Expectations has a truly ridiculous obsession with the idea of portable property, to the exclusion of all other forms of investment. In Part 22 of Dickens’ novel, Pip wishes to invest in Herbert’s business, but is told by Wemmick that this would be a terrible idea. When Pip turns up at Walsworth to further question Wemmick, we then meet the character of Miss Skiffins who is sporting a brooch, believed by Pip to be one of Wemmick’s various pieces of portable property. So, in Great Expectations, there is a focus on portable property, and negative sentiments towards business investment, but is this a feeling limited to Dickens, or is it to be found in other aspects of Victorian society? Through the method of reading sideways, and examining the other stories to be found in All The Year Round and Harper’s Weekly, published alongside Part 22 of Great Expectations, as well as by examining “Commodity and Identity In Great Expectations” by Sean Grass, we will discuss the Victorian obsession with things, and how this also translated into an avoidance of commerce ventures.

CRITICAL SOURCE - SEAN GRASS

It is believed that when Dicken wrote Great Expectations, he was experiencing some of the greatest financial responsibility of his life(Grass 618). He was paying for separate residences for himself, his wife, and his mistress, was setting up two of his sons in business careers, and had been left to take charge of his brother’s widow and children(Grass 618). Great Expectations is also greatly concerned with monetary matters, and in light of Dickens’ troubles when he wrote it, takes on an autobiographical tone(grass 618). Great Expectations is not however, a portrait of Dickens, but instead an imaginative take on an issue growing among Victorian society to commodify subjects(Grass 619). Pip commodifies Estella(Grass 619). The Victorian public commodified the latest Dickens novel, or the newest style of dress. But engaging in business was another matter.

In the case of characters within Great Expectations they take on the role of the neurotic Victorian, attempting to avoid engaging in capitalist actions, whilst still commodifying subjects. Miss Havisham after being left at the altar, decided to invest her money and time into Estella, thus commodifying her, rather than a legitimate business venture(Grass 623). Wemmick has his collection of curiosities in Walworth, which represent portable property, rather than proper business, and are thus considered separate from Wemmick’s job with Jaggers(Grass 623). Even Pip himself serves as a commodity for Magwitch, who could have gotten revenge on people by becoming a successful businessman, but instead decided he had to own a gentleman. In all these cases, however, that commodification of which the Victorians were so fond is occurring, and at the detriment to what could be considered investment in legitimate business. In our various artefacts from the magazines Dickens published in, we will now examine this avoidance of business ventures, and how the stories and advertisements we will explore reflect this avoidance, whilst emphasizing the need for commodities, or “portable property.”

Under The Golden Feet

In this story, a merchant ends up imprisoned in Burma, after illegally smuggling out goods. In Great Expectations, Pip asks Wemmick how to make his money stretch to allow for investment in Herbert’s business. Wemmick tells Pip it is a bad idea, as seen in the following block quotation,

"Mr. Pip," said Wemmick, "I should like just to run over with you on my fingers, if you please, the names of the various bridges up as high as Chelsea Reach. Let's see; there's London, one; Southwark, two; Blackfriars, three; Waterloo, four; Westminster, five; Vauxhall, six." He had checked off each bridge in its turn, with the handle of his safe-key on the palm of his hand. "There's as many as six, you see, to choose from."

"I don't understand you," said I.

"Choose your bridge, Mr. Pip," returned Wemmick, "and take a walk upon your bridge, and pitch your money into the Thames over the centre arch of your bridge, and you know the end of it. Serve a friend with it, and you may know the end of it too,—but it's a less pleasant and profitable end(Dickens 99)."

Thus, In Under The Golden Feet, we are shown another way in which business might not be the best option to engage in. Mr. Gouger, the merchant who gets imprisoned, is starved and beaten as a result of his less than wise business venture, which could be seen as the “less pleasant and profitable end,” that Wemmick describes as a result of unwise business dealings.

As for why those business dealing were unwise, The Burmese are described as being, “strict protectionists, exclusive and conservative, they were not very inviting people to deal with(All The Year Round 102). The writer of Under The Golden Feet goes on to describe the decision to do business in Burma, thusly, “The more certain a man is of getting his throat cut, the more eager he is to try his fortune in the very spot where the razor is being sharpened(All The Year Round 102).” We can relate this line back to our critical source from Grass, however, as the reason the merchant is doing business there is because he has commodified the idea of Burma being dangerous, and the Victorian public who would buy his goods have commodified the goods from Burma due to this element of risk. Preferably, however, would be to not be at risk.

My Holiday

This particular poem comes right after Great Expectations and Under The Golden Feet. Now, a repeated theme with the character of Mr. Wemmick in Great Expectations is that one needs to keep work life and home life separate. He has a house in the suburb of Walsworth, which he has made to look like a castle, complete with a cannon and a drawbridge. It’s a bit of a fantastical place, and Wemmick uses the thought of going home as a way of coping with his job as a lawyer, as he knows that when he is at the Castle, as he refers to his house, he does not need to be as cold and aloof as he does at the office. When Pip inquires as to whether Wemmick’s opinion on investing in Herbert would change at Walworth, Wemmick reply is thus, “Walworth is one place, and this office is another. Much as the Aged is one person, and Mr. Jaggers is another. They must not be confounded together. My Walworth sentiments must be taken at Walworth; none but my official sentiments can be taken in this office(Dickens 99).”

Stanza 3 of “My Holiday” seems to reflect this sentiment of Wemmick’s particularly well,

“And losing here all sense of wrong,

I feel no more the clutch of care,

And dream a world of light and song

Where all are happy, all is fair.

But o'er me, steals the envious eve,

And spreads a veil of sober grey,

When, as I take reluctant leave,

A glory dies along the way(Macfarlan 107).”

Wemmick does not like working for Mr. Jaggers. He does however take great joy out of going home to the Castle. Being at the castle also means that Wemmick is no longer obligated to provide Pip with sound business advice, and can instead indulge him, by arranging to talk to Miss Skiffin’s brother, who is an accountant. Wemmick is also no longer concerned about portable property to the same degree as he is when at work, and forgets all the ways that business ventures can go drastically wrong.

Grass speaks of commodifying subjects, and looking at Wemmick’s separation between his job and living place, we can see an element of commodification occurring as it relates to the Castle. The Castle is peace and tranquility, and everything the office is not, even though in truth, it is a suburban home, and not actually of particular value outside of the sentimental.

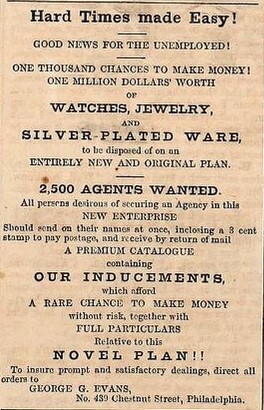

Hard Times made Easy!

The opening lines of the two chapters this part of Great Expectations covers directly deals with the idea of going into debt as a result of poor financial decisions. This advertisement, which was on the page after Great Expectations in Harper’s Weekly, seems to be the Victorian equivalent of a modern-day pyramid scheme. It is specifically targeting those, who like Pip and Herbert are in desperate need of money, as seen in this quote,

“Herbert and I went on from bad to worse, in the way of increasing our debts, looking into our affairs, leaving Margins, and the like exemplary transactions; and Time went on, whether or no, as he has a way of doing; and I came of age—in fulfilment of Herbert’s prediction, that I should do so before I knew where I was(Dickens 97).”

In opposition to Wemmick’s position on the idea of investing in Herbert, mainly that it is a risk, this advertisement is promising “A RARE CHANCE TO MAKE MONEY without risk(Harper’s Weekly 271).” This advertisement is taken from Harper’s Weekly, and being an American magazine could be seen as an extension of the American Dream which promises success to those who come to America. In this case, success is promised to those who sign up to become purveyors of portable property, however.

If we relate things back to Grass, we can also see the commodification at play in the advertisement. The items being sold are luxuries such as jewelry and watches, and with the Victorian obsession with things, we can see how the commodification of those luxuries is being used to promise riches and success to those selling the luxuries(Grass 617).

Fire In A Coal-Mine

In this article, which comes after “My Holiday” the reader is yet again reminded of the risks of business ventures. The writer is the inspector for a coal mine, and whilst he is down there, the mine experiences a fire, which traps the inspector and a number of workers down in the mine. Now, a coal mine is certainly not remotely similar to the portable property which Mr. Wemmick is such an ardent fan of. Certainly, in the case of this article, it is nowhere near as safe as portable property. Only the inspector and two miners made it out of the mine alive. Mr. Wemmick advises Pip that in terms of investing in business, “Serve a friend with it, and you may know the end of it too,—but it's a less pleasant and profitable end(Dickens 99)." In the case of this mine inspector, he saw exactly how final that end could be, with his making it out of the mine alive being a miracle, and not a miracle shared by the others trapped in the mine. There’s also the damage to the mine itself to take into account from an investment point of view. “but so great had been the force of the explosion and the amount of damage done, that it was not until the fifth day after the

accident that we were found(All The Year Round 110),” Mines, and other businesses have the potential to cost more money than they make. Portable property is far safer and less likely to go badly for those dealing in such goods.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, by reading sideways in the two magazines Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations was published in, both All The Year Round, and Harper’s Weekly, we are given a glimpse into the economics of the Victorian Era. We can see how commodification was king, leading to a great rise in obsession with portable property, as the character Wemmick in Great Expectations echoes. On the flipside however, we can also see how other forms of investment were discouraged, with the potential for imprisonment, or death being seen in other stories in All The Year Round, such as in Under The Golden Feet, and Fire In A Coal-Mine. With such drastic consequences displayed for those who woud undertake capitalist business ventures, we cna understand why portable property would have been preferred, as seen with the advertisement from Harper’s Weekly. The advertisement promises the opportunity to make money without risk. This would be through the sale of portable property such as watches and jewelry. With two such drastically contrasting messages presented to the public, we can see why Victorians would have preferred portable property over other business ventures.

Works Cited

Grass, Sean. “COMMODITY AND IDENTITY IN ‘GREAT EXPECTATIONS.’” Victorian Literature and Culture, vol. 40, no. 2, 2012, pp. 617–41. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41819960. Accessed 5 Apr. 2023.

Harper's Weekly, vol. 5, no. 226, 27 Apr 1861, p. 271. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv5bonn/page/270/mode/2up

Macfarlan, James. "My Holiday." All The Year Round, vol. 5 no. 105. 27 Apr 1861, p. 107. Dickens Journals Online. https://www.djo.org.uk/all-the-year-round/volume-v/page-107.html

Unknown. "Fire In A Coal-Mine." All The Year Round, vol. 5 no. 105. 27 Apr 1861, p. 107-110. Dickens Journals Online. https://www.djo.org.uk/all-the-year-round/volume-v/page-107.html

Unknown. "Under The Golden Feet." All The Year Round, vol. 5 no. 105. 27 Apr 1861, p. 102. Dickens Journals Online. https://www.djo.org.uk/all-the-year-round/volume-v/page-107.html

Unknown. "Fire In A Coal-Mine." All The Year Round, vol. 5 no. 105. 27 Apr 1861, p. 107-110. Dickens Journals Online. https://www.djo.org.uk/all-the-year-round/volume-v/page-107.html