Part 24

Introduction

Charles Dickens’ novel, Great Expectations, was originally published in Harper’s Weekly in the United States and All The Year Round in the United Kingdom. It is important to note the difference between the layout of the original publication of Great Expectations appearing in All The Year Round in comparison to Harper’s Weekly. The illustrations and advertisements appearing in Harper’s do not appear in All The Year Round. Harper’s Weekly holds greater influential power to how our reading of Dickens’ novel is read in comparison to All The Year Round, due to the publishing advertisements, other stories, illustrations, jokes, etcetera published in the former and the lack thereof in the latter.

Part 24 of Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations—originally published May 11th, 1861—is a very crucial chapter in the novel, as we learn that Pip’s benefactor, who is responsible for funding Pip’s journey to becoming a gentleman, is Magwitch, the escaped convict whom Pip helped as a child, rather than Miss Havisham, Estella’s guardian. This shocking revelation upsets Pip’s understanding of how he became a gentleman, which leaves him feeling guilty for abandoning Joe. There is a great deal of reflection on Pip’s past in this chapter, which is enhanced through advertisements and pictures published alongside the chapter in Harper’s Weekly. Through analysis of the adjacent publications in Harper’s Weekly, close reading of part 24 of Dickens’ Great Expectations, and the insights of Toru Sasaki in their peer reviewed article, we will explore the relevance of power, death, and marriage in Pip’s certain circumstances.

Regiment and The Illusion of Power

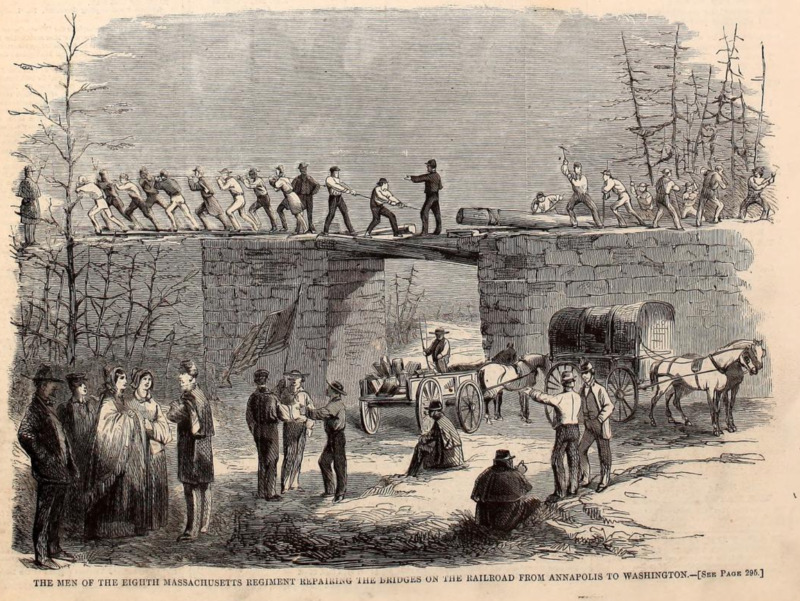

The illustration of “The Men of the Eighth Massachusetts Regiment Repairing the Bridges on the Railroad from Annapolis to Washington” published in Harper’s Weekly in association with this chapter really emphasizes the protective and paternal role that Magwitch feels that he took on in becoming Pip’s benefactor. Upon his arrival, Magwitch is very welcoming and loving to Pip, extending both arms out to him. Pip is put off by Magwitch’s actions, and further put off when Magwitch declares “Lookee here, Pip. I’m your second father. You’re my son – more to me nor any son” (Dickens 346). Magwitch is proud to proclaim that he has put all of his earnings into Pip becoming a gentleman, and needs Pip to understand that Magwitch views him as his son. The illustration of a military regiment repairing a bridge is quite significant to this chapter. The bridge between Magwitch and Pip, theoretically, is burned during their encounter in Pip’s childhood. Since that point in time, Magwitch has been silently putting money into Pip to aid him in becoming a gentleman. Seeing this image prior to reading this chapter in Harper’s Weekly, one might read this chapter from a standpoint that Magwitch is attempting to repair the bridge between him and Pip in order to repair their relationship, just as the men of the eighth regiment were repairing the bridge in the illustration. Furthermore, this illustration could represent a metaphor for the relationship between these two men.

Pip is not interested in apologies from Magwitch, as he declares “If you are grateful to me for what I did when I was a little child, I hope you have shown your gratitude by mending your way of life” (Dickens 343). Magwitch most certainly mended his way of life, and dedicated his earnings to facilitating Pip to become the gentleman that Magwitch never was. Magwitch takes full responsibility for Pip becoming a gentleman in this chapter, as he declares “Yes, Pip, dear boy, I’ve made a gentleman on you! It’s me wot has done it!” (Dickens 346). This quote demonstrates the power and pride that Magwitch possesses in regard to his actions. This power and pride is also felt in a military role, as one would feel pride and power in protecting their country, which connects to illustration to Magwitch’s emotional attachment to Pip.

"A Voyager By The Sea" (Dickens 341)

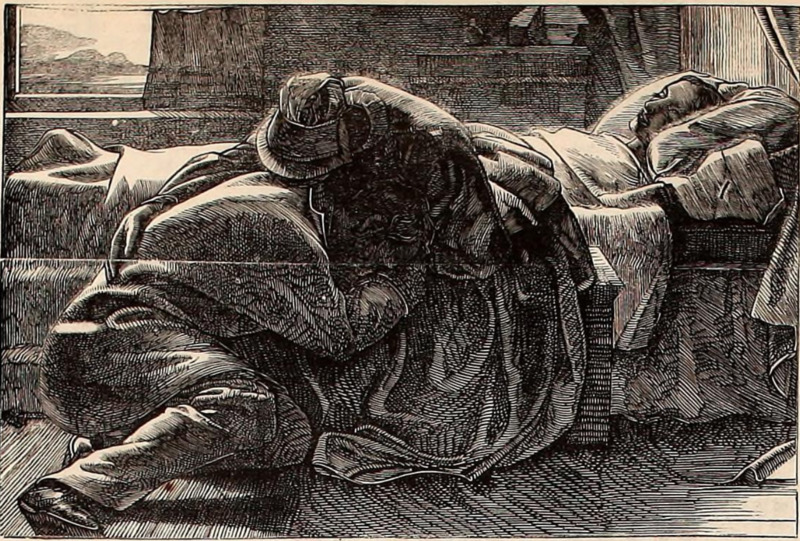

The placement of the “Sailor’s Bride” poem, alongside the illustration of a man slouched over a woman on her deathbed, is a factor of the original publication in Harper’s Weekly that can heavily alter the reading of this text. In particular, it forces us to ponder on Pip’s relationship with his sister. When Pip was young, his relationship with his sister was not of a healthy nature. She was abusive to him and to Joe. Yet, her death still haunts Pip. The illustration of the woman on her deathbed reminds us of the significant role that Pip’s sister played in his life, in parallel to the haunting presence she now has left Pip. The lingering presence of Mrs. Joe alongside Magwitch’s appearance in this chapter displays a chilling parallel of Pip’s past, especially with Magwitch’s steps resembling that of his sister: “What nervous folly made me start, and awfully connect it with the footstep of my dead sister” (Dickens 341).

The mention of a sailor holds great weight in part 24 of Great Expectations. Not only is the weather “wretched …; stormy and wet, stormy and wet; and mud, mud, mud, deep in all the streets” (Dickens 340), but Magwitch comes to Pip appearing “substantially dressed, but roughly; like a voyager by the sea” (Dickens 341). The nostalgia at the beginning of this chapter brought about by the storm, alongside the chilling and eerie presence that looms when Mrs. Joe is mentioned after her death, sets the mood for the shocking revelation of Pip’s benefactor that occurs in the final chapter of volume two of the Broadview novel.

Can Matrimony Truly Be Made Easy?

The notion, proven false in this chapter, that Miss Havisham is Pip’s benefactor was giving Pip some form of faith that he could become a man who is fit to marry Estella. Pip believed that Miss Havisham was funding his journey to becoming a gentleman in order for him to wed Estella. When Magwitch reveals that he is Pip’s benefactor, rather than feeling excitement at the revelation of this secret, one of Pip’s first thoughts is “O Estella, Estella!” (Dickens 347). He has taken one step further away from Estella in learning that his benefactor is not from her family, and in turn, he feels even further disconnected from her. The irony of Pip’s grief from this revelation with the statement “Matrimony made Easy!” is comical. The blurb gives the statement that “either sex may be suitably married, irrespective of age or appearance”. If Pip could read this blurb, he may feel an air of hope that he could be properly suited to marry Estella, despite his lack of a gentleman appearance; this hope would be crushed if he continued to read that the findings of this new study were “free for 25 cents”, adding to the humour of the situation. Love is not an exact science; there is no formula. Pip becoming a gentleman is not the sole missing piece in the equation. The public in 1861 could not be given the answer to how matrimony could be made easy, nor could Pip find a solution to easy matrimony in Great Expectations.

Ladies, What Are You Capable Of?

The blurb addressed “To the Ladies,” adjacent to part 24 of Great Expectations, mentions a method of how to achieve beautiful glowy skin. This alludes to stereotypical beliefs of the Victorian woman, that she is more beautiful than she is smart. The mention of beauty brings Estella to mind, as Pip gawks throughout the novel as to how beautiful Estella is; she is not actively in part 24 of Great Expectations, but is mentioned passively as Pip’s first thoughts after finding out the true identity of his benefactor are, “O Estella, Estella” (Dickens 347). Toru Sasaki in their peer reviewed article, “What Estella Knew: Questions of Secrecy and Knowing in Great Expectations,” argues that Estella knew much more than she let on about the true identity of Pip’s benefactor. Now, perhaps she did not know that Magwitch was this benefactor, but Sasaki ruminates on her reaction to Pip’s news, in that “Estella pauses for a moment, then goes on knitting. Pip recalls: ‘I fancied that I read in the action of her fingers, as plainly as if she had told me in the dumb alphabet, that she perceived I had discovered my real benefactor’ (268; ch. 44)” (Sasaki 182). Sasaki interprets Estella’s behaviour as follows:

“Given the circumstances, the most plausible scenario I can come up with is as follows: Pip erroneously fancies that Estella has perceived the truth at this moment; she has previously been ignorant but has only very recently come to know about Pip’s real benefactor not being Miss Havisham; for some reason Miss Havisham herself has told her.” (Sasaki 183).

Sasaki’s rumination on Estella’s ability to obtain and withhold such knowledge is an interesting tie with the blurb appearing in Harper’s Weekly adjacent to this chapter in which Pip learns that his benefactor is, in fact, not Miss Havisham.

Conclusion

The ads and illustrations adjacent to and surrounding part 24 of Dickens’ novel, Great Expectations, appearing in the original publication in Harper’s Weekly, enhance Pip’s struggles with power, death, and love. Magwitch gives power to himself while simultaneously taking it away from Pip as he reveals that he has been Pip’s benefactor, funding his road to becoming a gentleman. Prior to the reveal of Magwitch, Pip is reminded of his dead sister, which inspires us as readers to reminisce on Pip’s past. The illustration of the man mourning the woman in her deathbed enhances this memory of the late Mrs. Joe. Furthermore, the blurb addressed “To the Ladies”, despite the fact that there are no ladies explicitly present in part 24 of Great Expectations, suggests an important role of the woman in this part of the novel. Sasaki argues that this important role of the woman in this part is the knowledge that Estella and Miss Havisham possess, as it is suggested that they both knew the true identity of Pip’s benefactor before they were explicitly told by Pip. As we have explored, the ads and illustrations present in the Harper’s Weekly publication of Dickens’ Great Expectations enhance the reading of this chapter.

Works Cited

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. Edited by Graham Law and Adrian J. Pinnington,

Broadview Press, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. "Great Expectations: Chapter XXIX." Harper's Weekly, vol. 5, no. 302, 11 May 1861.

McLenan, John. Illustrator. "The Men on the Eighth Massachusetts Regiment Repairing

the Bridges on the Railroad from Annapolis to Washington". Harper's Weekly, vol.

5, no. 302, 11 May 1861.

McLenan, John. Illustrator. "The Sailor’s Bride". Harper's Weekly, vol. 5, no. 302, 11 May

1861.

Sasaki, Toru. “What Estella Knew: Questions of Secrecy and Knowing in Great Expectations.”

Dickens Studies Annual, vol. 48, no. 1, 2017, pp. 181–90,

https://doi.org/10.5325/dickstudannu.48.1.0181.

“Matrimony made Easy!” Harper's Weekly, vol. 5, no. 302, 11 May 1861.

“To the Ladies.” Harper's Weekly, vol. 5, no. 302, 11 May 1861