Part-27

Introduction

Throughout academic and pop culture settings, the relationship between Estella and Pip is a central topic of discourse surrounding Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations. Even in the midst of the American Civil War, topics surrounding romance and gender roles persist. In Harper’s Weekly publication of the twenty-seventh part of Great Expectations, advertisements and a selected illustration focus on romance and the regulation and problematization of women. Margaret Darby’s article, “Listening to Estella,” focuses on “an Estella-centered reading of their [Pip and Estella’s] relationship” (217) and argues that such a reading “documents the deafness of her world .”Darby’s argument can be expanded to argue that the world of Harper’s Weekly is also deaf to Estella’s world and focuses on a Pip-centered reading. Though Dickens may offer more agency and expand the role of women through Estella, the use and placement of advertisements in Harper’s Weekly supports the view of women as a wife and sympathizes with Pip. The advertisements and illustration portray Estella as an “unnatural” woman needing a cure.

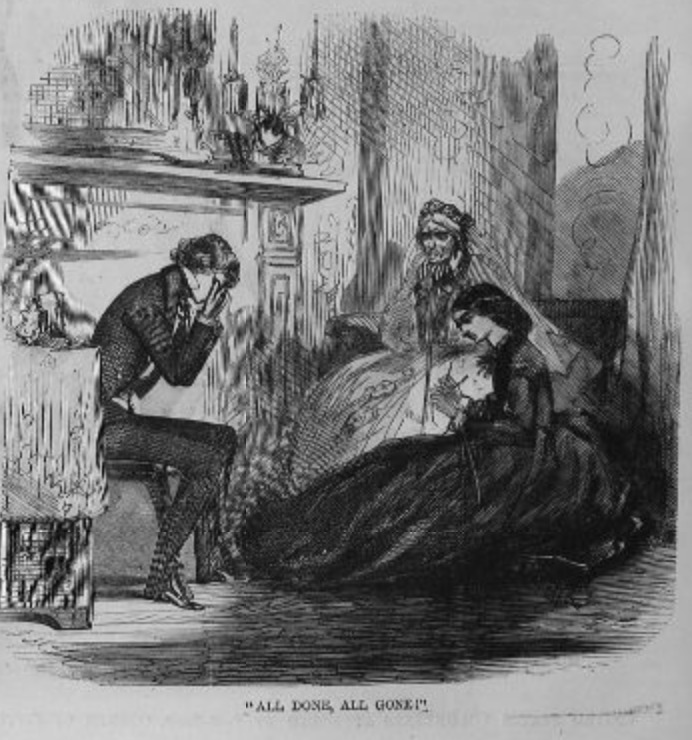

All done, All gone!

The sole illustration for the twenty-seventh installment of the novel reveals what the magazine believes to be the pivotal moment in the installment and pleads for Pip’s sympathy. The caption “all done, all gone!” (Harper’s 350) is a direct quote from the novel. However, Pip’s statement does not refer to the action illustrated above; instead, it is a thought that Pip, as the narrator, inserts after he has left Miss Havisham and Estella. Additionally, his expression is open-ended and may refer to several issues, such as his financial situation, his patron’s reveal, or his concern for Estella. However, the illustrator’s choice in placing the quote to represent Pip’s conversation with Estella and Miss Havisham supports the reading of the quote to refer to his relationship with Estella and centers it as Pip’s most significant concern. Arguably, Pip’s depiction in the illustration has the most expression and distress, which leads readers to feel sympathy for him. What the illustration ignores by placing Pip as the sole “sufferer” is Estella’s voice and Pip’s unacceptance of her agency. While the image appears as though Estella is heartless, the novel highlights Estella’s battle to create a life different than what Miss Havisham and Pip imagine her to have. Estella verbally expresses how Pip has continuously ignored her wishes against romance. She states, “What have I told you? Do you still think, in spite of it, that I do not mean what I say?” (Dickens 386). Regardless of what contributed to Estella’s rejection of romance, she has consistently relayed her lack of love, yet the illustration still calls for sympathy for Pip. Darby notes that Estella’s “frequent warning she has no heart” suggests “she has a heart for kindness, if not for love” (224). Therefore, the illustration suggests that it is because she has said no countless times and does not conform to gender expectations of obedience that readers are to feel sympathy for Pip. Doing so restricts Estella’s agency and contributes to how Pip has ignored Estella.

Wedding Cards

While Estella has rejected Pip, she mentions she will marry Drummle (Dickens 387), which Harper's Weekly highlights with an advertisement for Wedding Cards(Harper's 351). Similar to the illustration, the advertisement placement ignores Estella's voice and her reasoning for marrying Drummle. While Pip has attributed Estella's marriage to Drummle with Miss Havisham, Estella clarifies that it is her "own act" (Dickens 387). She further states that though she does not love Drummle, she will marry him to change her life (387). Her reasoning behind her marriage reflects women's restricted space in the novel and Estella's attempt to use whatever agency she has to get away from the life Miss Havisham has decided for her. Furthermore, her choice reveals that Estella does not believe there is any way out of marrying. Despite the dark reasoning behind Estella's marriage, the placement of the ad reflects society's value on the institution of marriage. Furthermore, the emphasis on marriage shows society's importance on maintaining the structure of marriage rather than upholding romance, especially when readers witness Pip's grand proclamation of love ending in rejection. Emphasizing Estella's wedding rather than her limited choices employs the gender role of the woman as a wife. The ad hopes to place Estella in a place of "normality," especially when her views go against traditional gender roles and desires.

A New Thing Entirely

Though the above ad is for a breath purifier, the ad makes the product for female consumers (Harper’s 351). Interestingly, the description uses the word “sweetens,” which can be understood as gendered language catering to the ideal view of women as sweet and obedient. Furthermore, the emphasis on sweetening the breath “no matter how affected” reveals vague language in that “affected” could also apply to strong emotions felt by a woman. Purifying strong emotions reveals the belief that women should not have intense feelings of anger or joy. The advertisement connects to the serial as it could be a symbolic way to show discontent with Estella’s words to Pip. Her words of rejection and emphasis on choice may be understood as “foul” and needing purification. The idea of purifying Estella’s words places readers in a Pip-centered reading that villainizes Estella for not wanting romance and sympathizes with Pip. Sympathizing with Pip reveals an emphasis on maintaining a patriarchy that seeks to silence the voice of women who do not want certain men.

Sands' Sarsaparilla

Like the breath purifier, Sands Sarsaparilla is a blood purifier catered to women (Harper’s 351). Placing Estella into the context of the ad instills the notion that Estella is unnatural or sick and needs medicine. Pip also holds the advertisement’s theme of purifying blood. For example, when Estella reiterates that she has warned Pip of her incapacity for romantic love, Pip states, “I thought and hoped you could not mean it. You, so young, untried, and beautiful, Estella! Surely it is not in Nature” (Dickens 386). Pip’s emphasis on “Nature” suggests that he believes something is wrong with Estella’s view since it does not follow his idea of how women should act. He believes there is a particular “nature” or way of being that all women should follow and is shocked when Estella does not conform to his fantasy. Despite the countless times Estella has denied his romantic advances, Pip ignores them due to his idea of gender roles. Specifically, Pip believes that her denial of romance are feminine ways to encourage his pursuit, thereby showing his lack of understanding of consent. Additionally, the focus on “Nature” and the advertisement’s emphasis on blood can relate to Pip’s view on Estella’s upbringing and DNA. In Pip’s statement on Estella’s nature, he believes Estella’s lack of feeling to be a result of her biological bloodline and her environment with Miss Havisham rather than an expression of her identity. Therefore, the ad can represent the need to clean Estella’s upbringing and her biological connection to her mother, Molly. However, as Darby notes, “what Pip finds heartless is her insistence on her own point of view” (221). The idea that Estella is only a product of her environment and her DNA suggests that Pip does not view Estella as a human being outside of biology and environment. Therefore, the ad reflects just another aspect in which Pip has objectified Estella and continues to deny her agency. Furthermore, the advertisement can be expanded to include all other women deemed unnatural because they do not fit within the patriarchy’s view of women as passive accepters of love.

Interestingly, since the ad has a female focus, Pip’s connection to the lower class is erased. Due to Pip’s expectations, he has risen in class despite “naturally” being born into the lower class. If anything, Pip should be the one in need of a blood purifier to gain acceptance into his new status. However, Estella’s “impurity” is highlighted.

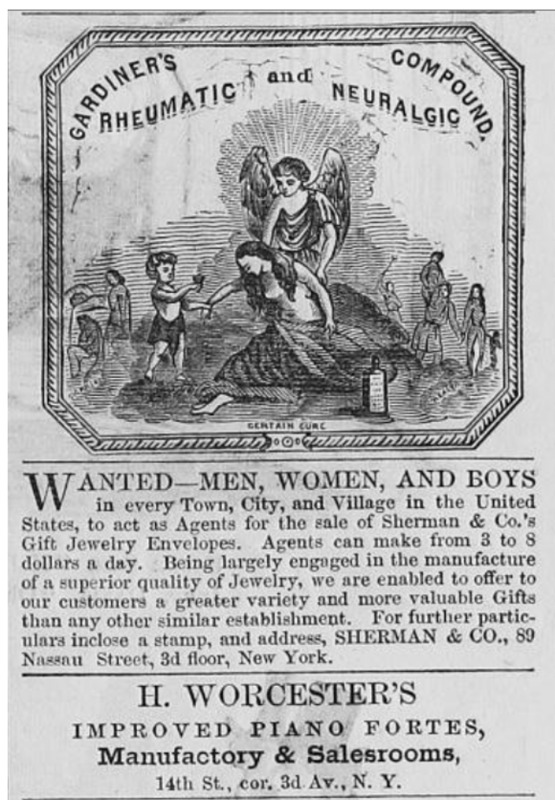

Wanted

The advertisements for a Rheumatic and Neuralgic compound and employment for gift Jewelry envelopes (Harper’s 351) reinforce Estella’s “sickness” and her objectification. The Gardiner’s compound advertisement consists almost entirely of an illustration which sets a female body at the center. Again, emphasizing the female body as the primary source of sickness highlights the desire to regulate the female body and mind to fit within a strict social standard. Applying the commercial to Estella reinforces that she is sick for not adhering to romantic ideals as an obedient woman.

Viewing the search for agents of Gift Jewellery Envelopes in relation to Great Expectations reveals how Pip views Estella as a form of jewellery for himself. As stated earlier, Pip believes that Estella did not mean her rejection, and he expresses, “You, so young, untried, and beautiful” (Dickens 386). His statements reveal his objectification of Estella and his one-sided view of her as an ornament rather than a person. Darby represents this idea by stating that Pip views her as “a coveted abstraction of social and sexual assets” (226). Like jewellery envelopes, obtaining Estella is the “cherry on top” to represent Pip’s rise to the upper class and will allow his acceptance into high society. The advertisement places Pip’s point of view at the forefront by focusing on embellishments and objects of social capital. Furthermore, Darby notes that “Dickens conveys the immediacy, even tragedy of her perspective, ‘I and the jewels’…but Pip hears only his own name” (224). Darby’s statement reflects Pip’s self-centeredness and Estella’s awareness of her perspective being thrown aside. Like Pip, featuring the ad on jewels erases Estella’s saddening association with property and beauty. She is continuously fighting to be understood as a person, and Pip continues to put her in a place of victimhood, beauty and role as a wife.

Conclusion

Reading the advertisements in Harper's Weekly in relation to Charles Dickens's Great Expectations reveals how the magazine views Estella with a Pip-centered lens that villainizes her. The ads centred on Pip's perspective and purification of several aspects of a woman depict Estella as sick and needing help, specifically from a male audience. Despite Estella having a voice in the novel, magazine readers are shielded from it. As a result, one must question how different readers are from Pip if the media they consume validate his narrative.

Works Cited

Darby, Margaret F. "Listening to Estella." Dickens Quarterly, vol. 16, no. 4, 1999, pp. 215. ProQuest, https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/listening-estella/docview/1298037957/se-2.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. Edited by Graham Law and Adrian J. Pinnington, Broadview Press, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. "Great Expectations: Chapter XLII." Harper's Weekly, vol. 5, issue 231, 1861. EBSCOhost. https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=h9k&AN=66539640&site=ehost-live&kw=true&acc=false&lpId=divl12&ppId=divp14&twPV=&xOff=0&yOff=0&zm=fit&fs=&rot=0&docMapOpen=true&pageMapOpen=true

"A New Thing Entirely." Harper’s Weekly, vol. 5, Issue 231, 1 June 1861, p. 351. EBSCOhost,https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=h9k&AN=66539640&site=ehost-live&kw=true&acc=false&lpId=divl31&ppId=divp15&twPV=&xOff=250&yOff=17&zm=3&fs=&rot=0&nobk=y&docMapOpen=true&pageMapOpen=true

"Sands' Sarsaparilla." Harper's Weekly, vol. 5, Issue 231, 1 June 1861, pp. 351. EBSCOhost,https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=h9k&AN=66539640&site=ehost-live&kw=true&acc=false&lpId=divl31&ppId=divp15&twPV=&xOff=0&yOff=556&zm=2&fs=&rot=0&docMapOpen=true&pageMapOpen=true

"Wanted." Harper's Weekly, vol. 5, Issue 23, 1 June 1861, pp.351. EBSCOhost, https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=h9k&AN=66539640&site=ehost-live&kw=true&acc=false&lpId=divl12&ppId=divp15&twPV=&xOff=250&yOff=979&zm=3&fs=&rot=0&docMapOpen=true&pageMapOpen=true

“Wedding Cards.” Harper’s Weekly, vol. 5, Issue 231, 1 June 1861, pp. 351. EBSCOhost,https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=h9k&AN=66539640&site=ehost-live&kw=true&acc=false&lpId=divl29&ppId=divp15&twPV=&xOff=0&yOff=0&zm=fit&fs=&rot=0&nobk=y&docMapOpen=true&pageMapOpen=true