Part 3

Crime during Victorian London was not fuelled directly by ethical judgement. Many crimes went unreported due to the lack of faith in the police. Depending on an individuals status in society, said status would encourage the police to genuinely and thoroughly look into the crime; or the exact opposite. Not only were some crimes going unnoticed, industrialization was rapidly changing London and the environment itself. Poverty was rising and along with that, crime. While crime can be committed by sadistic forces, survival instinct presented major motives. Charles Dickens plays around with the theme of justice and crime quite often in his novel, Great Expectations. Within the novel, there have either been characters who have dealt with crime and no justice, or characters who have committed a crime, fearing judgement. Below, there are illustrations from the novel itself, other works, and articles that appear quite similarly to the scenes written in chapter 5. Along with a close reading, how are the thematic elements of justice and crime portrayed within the characters in this part?

Sands' Sarsaparrilla

The Sand brothers, Abraham B. and David Sands were businessmen who established their work in 1836 New York. Around 1839, their product, the "Sarsaparilla" was introduced. 19th century patent medicines regarded the Sand brother's new product as a "tonic...[which will help any person] find their nervous and general system strengthened and improved by its use” (Unknown). This medication was advertised to cure all ailments which is something Pip definitely needed throughout this entire novel. Pip is described to be “in an agony of apprehension” (Dickens 67) when the soldiers first arrive at his home. Once he came to the realization “that the handcuffs were not for [him]. . .[Pip] collected a little more of [his] scattered wits” (Dickens 67). His nervousness stems from his previous act of stealing food for the convict, but he was even more terrified that it may be “[his] particular convict” (Dickens 70). With Pip’s “heart thumping like a blacksmith” (70) he grew to question whether the convict would not only assume that Pip “brought the soldiers there. . .[but] that [he] was both imp and hound. . .and had betrayed him (70). While he had more of a sound mind knowing “the handcuffs were not for [him]” (67), he remained afraid. He doesn’t want to be arrested and he does not wish to face his cruel sister's verbal lashings. Pip did not wish to steal from his house but that was due to fear. During this time, many crimes were committed due to fear or survival. Either it was the fear of not surviving, or the fear of surviving long enough to be caught. Therefore, Pip's first action of crime inaugurates him into the world of fear, survival, and crime.

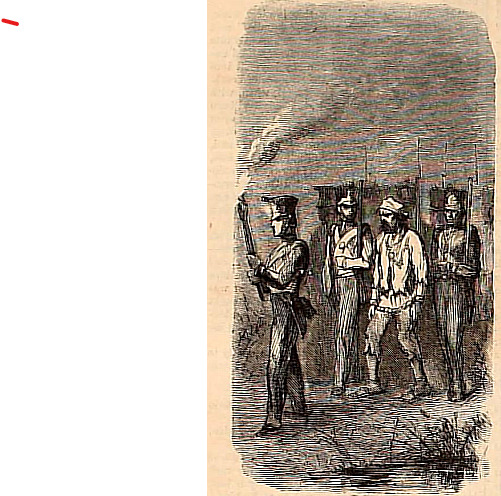

The Convicts

In Harper’s Weekly’s printed version of Great Expectations, the illustrator John McLenan has drawn an image of the convicts being transferred to the prison ships. As the soldier's guide the way, readers can observe that only one of the two convicts have been drawn. Out of the two convicts, “the other convict was drafted off with his guard to go on board first” (Dickens 75). Taking a creative outlook on the illustration, let us assume the convict is the same one Pip had aided. The soldiers had quite a way when they handled convicts. There is a lack of understanding or attentiveness. Whilst they are convicts, they are regarded as “wild beasts'' (Dickens 72). Criminals or not, they are still human. When Joe generously excuses the convict's confession to stealing pie, that act of kindness was a surprise to the convict. When Pip once again hears the “[clicking noise] in the man's throat. . .[as] he turned his back’ (Dickens 76), readers can assume the convict is clearing his throat due to tears. The convict was brought to tears of kindness because he was shown that there was someone to hear him out and just listen. The soldiers in the novel are depicted similarly to how the justice system treated convicts in the 19th century. There were two convicts with differing stories, yet they will both meet an identical end. Not only were they disregarded as actual people, the soldiers and Pips Christmas invitees “were all in lively anticipation of “the two villains” being taken” (Dickens 69). Knowing ahead of time that the convicts would be under scrutiny and would have to face terrible punishments, the soldiers, Pumblechook, Mr Wopsle and Mrs. Joe were “enjoying themselves so much” (Dickens 68); so much, it was as if desert had been served to them. They found enjoyment, whereas the convicts remain terrified for their future, knowing they may not have any say in what can happen to them. This particular convict had no one. When he boarded the ship, “no one seemed surprised to see him, or interested in seeing him, or glad to see him, or sorry to see him, or spoke a word [to the convict]” (Dickens 76). Completely disregarded.

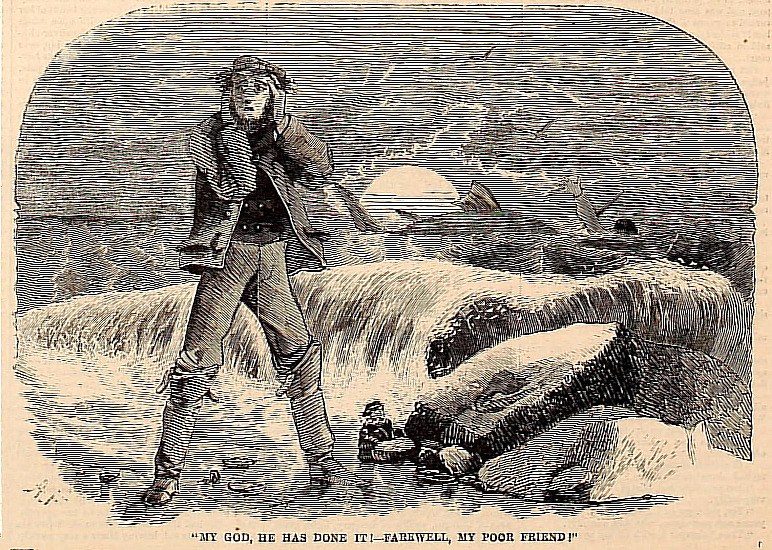

My god, he has done it! — Farewell, my poor friend!

This image from Harper’s Weekly comes from a “A True Shark Story” in which there is an illustration from an unknown artist. The drawing shows a horrified young man in front of moving water. Far into the water, there is a man possibly drowning. Whilst this illustration is not from the Great Expectations publication, there is quite a similarity in the emotion the young man expresses and how Pip feels when the convict spontaneously confesses to his “crime.” Leading up to this scene, the convict is brought into a wooden hut. By this time, the “convict never looked at [Pip]” (Dickens 75) and Pip is still terribly terrified of what the convict might say. Pip “had been waiting [all night for the convict] to see [him]. . .[simply so he could] try to assure him of [his] innocence” (Dickens 74). To his surprise, the convict confesses “without the least glance at [Pip]” (Dickens 76) to stealing a pie from Joe. Pip is in a state of awe and confusion. He spends the entire chapter worried that the soldiers have come for him or that they might find out about his wrong doings. Now that the convict has exonerated Pip, he believes that he is free from his guilt. Pip truly believes that the convict has left his life. This certain convict appears in many stages of Pip’s life. At this certain moment, readers are still at the beginning of their relationship, but it is not their end; not yet.

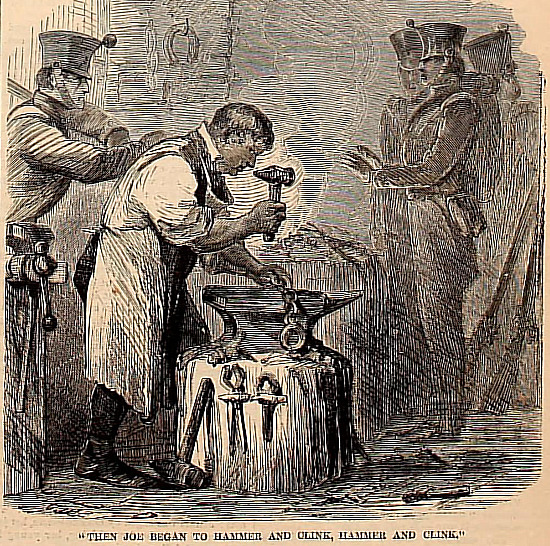

Joe the Blacksmith

Another illustration by John McLenan during the weekly publication shows Joe completing the task the soldiers had brought for him. In the illustration, Joe is fixing the cuffs. In chapter 5 of the novel, Joe once again has a moment in which readers can admire his generosity. The second image on this page speaks on the treatment of the convicts under the hand of the soldiers. In complete contrast, Joe was wholeheartedly kind towards the convict who confessed to him and the soldiers. Joe the Blacksmith was more than just that. Joe was a father figure, a husband, a role model, and a good person. Throughout the novel, Joe remains the definition of kind and understanding. Within all the images above, there has been a description of how crime has played a role for certain characters. When the convict confesses to Joe that he was “a man [who] can’t starve” (Dickens 76) and reveals he ate his pie, Joe did not call him derogatory animalistic terms the soldiers referred to. All a respectful man such as Joe exclaims that while he may not “know what [the convict has] done. . .[Joe] wouldn’t have [the convict] starved to death for it. . .[for] god knows [the convict is] welcome to it” (76). Joe is exactly what certain convicts needed. An individual who is willing to listen to them and understand their position. While he may “find language an alien and sometimes [an] incomprehensible system” or “lack the sort of social polish that Pip becomes so anxious to acquire. . .[Joe] exists on a level of physical grace and vitality” (Ousby 791). A man like Joe who Pip grew up to respect and admire, Pip knew what he feared more than getting caught; he feared “the loss of a sense of physical closeness. . .a silent communion with Joe” (Ousby 793). The way Joe is seen through Pip’s perspective allows readers to become comfortable with Joe’s kind heart. The justice delivered to many convicts was unfair and they were never truly heard. Their voices went ignored and perhaps Joe gives them the respect they may deserve solely because he knows far too well how it feels to be disregarded. HIs wife treats him as a servant. Pip grows to be embarrassed of him. He is known solely for his role as a blacksmith, but he has the biggest heart of all characters. Joe hopes from the bottom of his heart that the convicts “[have] cut and run” (Dickens 69) because that is who Joe is. A hopeful man.

Great Expectations has many thematic elements which were quite popular during Victorian era literature. Crime was one of those themes which rose to popularity, due to the changes in economy and industry. Due to many of those changes, certain individuals resorted to crime for survival; whether it be stealing bread from a local shop or pickpocketing. While it was a crime, many lead the life of these actions simply to see another day. Throughout the novel, there are many different examples of crime and how it impacted the lives of these characters. Were they kind and understanding like Joe? Or were they condescending and inattentive like the soldiers? Readers got to learn how each character responded to the crime surrounding their lives, but more importantly, the characters response and behavior allowed the readers to analyze their persona even further.

Works Cited

John McLenan. Great Expectations: A Novel by Charles Dicken. Harper’s Weekly, vol. 4, no. 206. 8 Dec 1860, pp. 773. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv4bonn/page/n771/mode/2up?view=theater

Jones, Radhika. Great Expectations. E-Book, Barnes & Noble, 2005.

“Life Scenes in the South” Harper’s Weekly, vol. 4, no. 207. 15 Dec 1860, pp. 796. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv4bonn/page/n795/mode/2up?view=theater

Ousby, Ian. “Language and Gesture in ‘Great Expectations.’” The Modern Language Review, vol. 72, no. 4, 1977, pp. 784–93. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3724673. Accessed 15 Apr. 2023.

“Sands Sarsaparilla.” Harper's Weekly, vol. 4, no. 207. 15 Dec 1860, pp. 799. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv4bonn/page/n797/mode/2up?view=theater

Sands’ Sarsaparilla Bottle. Sands's Sarsaparilla Bottle - Odyssey's virtual museum. (n.d.). Retrieved April 14, 2023, from http://www.odysseysvirtualmuseum.com/products/Sands%27s-Sarsaparilla-Bottle.html