Part 30

Paratexts and Plot: The Impact of the Publishing Context on Great Expectations

Introduction

Charles Dickens’ novel Great Expectations was originally published serially in both Harper's Weekly and All the Year Round from 1860-1861. These magazines not only included weekly chapters of Great Expectations, but news articles, illustrations, other fictional works, and advertisements as well. These paratextual items can be read alongside the chapters of Great Expectations to develop an understanding of the themes presented contemporary with the magazine's readership. In this essay, I argue how the paratextual context of both Harper's Weekly and All the Year Round further develop the themes of feminine gender roles and past versus present in Great Expectations to develop modern understandings of their significance. These themes are explored through the symbolism of fire, Miss Havisham's wedding dress, Stasis house, and Estella. Specifically, I will be focusing on chapters XLIX and L of Great Expectations and their respective magazine editions in both Harper's Weekly and All the Year Round.

To best illustrate my argument this essay is broken up into four sections, each analyzing a separate paratextual item. The first section will focus on the illustration by John McLenan published in Harper's Weekly and how it reinforces contemporary gender roles that punish women who occupy ‘masculine’ power. The second section will focus on a “Matrimony Made Easy” advertisement published in Harper's Weekly and how these notions of easy marriage are troubled by Miss Havisham and the destruction of her identity. The third section will discuss the themes of past and present in a short story titled, “My Young Remembrance” published in All the Year Round and how they complement these themes in Great Expectations. Finally, the fourth section will analyze “Day-Dreams”, an anonymous poem published in All the Year Round and extend the discussion of past versus present to the relationship between Estella and Provis.

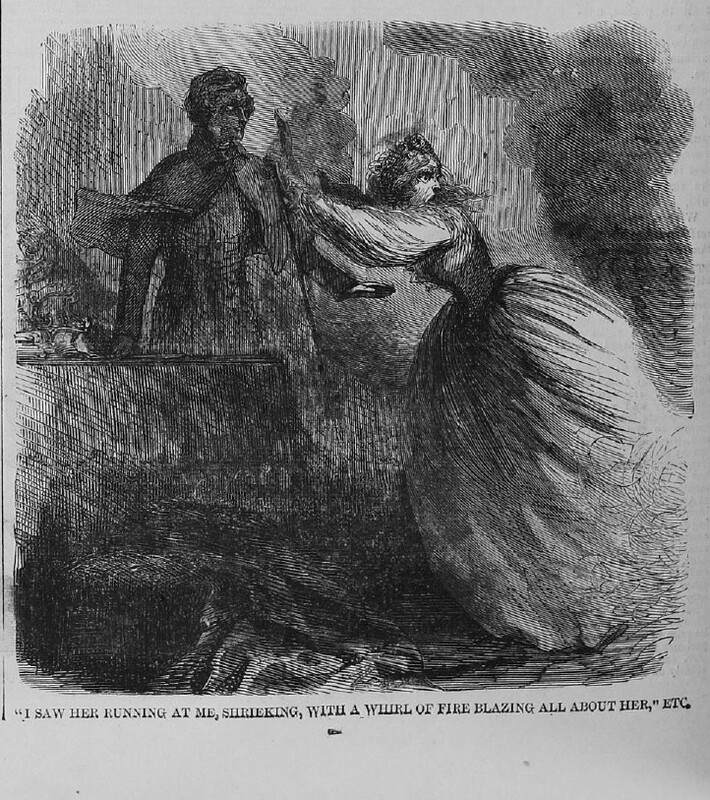

The illustration by John McLenan titled “I Saw Her Running at Me, Shrieking, with a Whirl of Fire Blazing All About Her” seen in Harper's Weekly develops the novel's contemporary gender norms and expectations. This is best seen through the ghastly depiction of Miss Havisham upholding ideals of spinster women as evil in contrast to Pip upholding norms that place men as voices of rationality. In the illustration, Miss Havisham appears deeply distressed: her body is contorted and her face a display of absolute terror (McLenan). This illustration enhances the text’s representation of Miss Havisham’s “white hair and worn face” as it portrays her as a ghostly, corpse-like figure (Dickens 421). Illustrating Miss Havisham in this way captures the contemporary demonization of spinster women who trouble patriarchal values by holding onto power. As discussed in the article, “A Re-vision of Miss Havisham: Her Expectations and Our Responses” she threatens patriarchal ideals as she “represents the Victorian male figure” in the way that “she owns the property and she possesses a female”, not conforming to ideals that admire childlike, powerless women (Raphael 408). Her male monetary power over Pip is flexed within this chapter as Miss Havisham gives money to Herbert to “complete the transaction [that was] out of [Pip’s] means (Dickens 419). In this way, Miss Havisham embodies a contemporary masculine role and such a transgression of patriarchy must be punished. The restoration of gender roles is seen in the depiction of her “manipulative witch-like figure” within the illustration and by her burning in the fire, much like a witch at the stake (Raphael 409). Miss Havisham is left “insensible” from the fire and “laid upon the great table” where she proclaimed to lie when she died (Dickens 425). Miss Havisham is left in a decrepit state as close to death as possible all as punishment for transgressing contemporary gender norms. It is in this way that the illustration further develops the understanding of gender roles within Great Expectations by depicting the gruesome punishment Miss Havisham faces for being in a traditionally masculine position of power.

While the “Matrimony Made Easy” advertisement promotes easy and successful marriage, when read alongside the struggles of Miss Havisham, it instead underscores how complicated marriage was during the time of its publication. T William & Co. advertise their publication that shows how any engagement “irrespective of age or appearance, [...] cannot fail”. These proclamations of marriage as an easily accomplished task are reversed as matrimony is not made easy for Miss Havisham. After being abandoned at the altar she is left in the past to mourn the loss of her identity as a married woman, forever living in the state of a bride-to-be dressed in her wedding gown. Raphael argues how Miss Havisham’s living in her bridal dress is a symbol of “[Compeyon’s] rejection which now becomes self-rejection” (Raphael 408). Her wedding dress then symbolizes how this failed attempt at marriage has destroyed Havisham’s ability to see herself as a whole person, as anything more than a fiance jilted at the altar. Raphael fails to consider how this lack of identity as a result of a failed attempt at marriage is also when Miss Havisham's wedding dress is destroyed in the fire: “though every vestige of her dress was burnt [...] she still has something of her old ghastly bridal appearance” (Dickens 425). Despite her wedding dress being destroyed, possibly freeing Havisham from this abandoned wife identity, her character has become so dependent upon revenge that is all she can be seen as. The now-destroyed wedding dress reflects how Miss Havisham’s identity was consumed by the flames of her “wild resentment, spurned affection, and wounded pride”, destroying who she was previous to her engagement to Compeyson (Dickens 422). Miss Havisham threw herself into marriage in the hopes of developing a new identity as a married woman, and when this pursuit burned down in flames, so too did her entire personality. Matrimony is something that is not made easy within Great Expectations, rather it is something that can be destructive and elusive, and the publishing context of this chapter only further underscores this notion.

Paratextual stories such as “My Young Remembrance” can be read alongside Miss Havisham's character to develop the themes of past and present within Great Expectations. In “My Young Remembrance” the narrator recalls the “old characteristics of those old times” in London (300). The narrator discusses the houses in Soho-square describing how they “are large, stately, and austere, with something of a gloomy magnificence about them, as if they lived in the mournful memory of better days, and drew a certain consolation from grizzling over their faded grandeur.” (“My Young Remembrance 301). This vivid imagery of the haunted, longing houses in Soho parallels both Miss Havisham's and Stasis house in how they are relics of the past. Miss Havisham remains a monument of the past as she “secluded herself from a thousand natural healing influences” and “[shut] out the light of day” (Dickens 422). Havisham, like the houses of Soho, cling to the past in magnificent and grim ways, refusing to modernize and change over time. Satis house is a relic of the past in how it embodies the mournful memories of the past. This is best seen in Pip's description of the rotted casks and abandoned garden that remain “so cold, so lonely, so dreary all!” (Dickens 424). While the garden recalls Pip's memories of the past when he fought with Herbert and walked with Estella it remains a decrepit garden, one that no longer fruits or flowers but remains in decay (Dickens 424). The author ends the reminiscent story with a call to its young readers: “be thankful for the age you live in, and don't revile the fountains any more.” (“My Young Remembrance 304). This call to action adds to the understanding of Pip’s forgiveness of Miss Havisham. Unlike Miss Havisham's inability to forgive and move on from her past hurt, Pip can forgive her for the hurt she has caused him when he states, “I want forgiveness and direction far too much, to be bitter with you” (Dickens 421). This forgiveness and ability to move on signify how Pip no longer wants to “revile the fountains” of the past as he moves on with his life and expectations (“My Young Remembrance” 304). “My Young Remembrance” captures the duality of past and present in its discussion of old London, paralleling both Miss Havisham's hold onto the past and Pip's ability to live in the present.

The motif of past and present is further demonstrated in the poem, “Day-Dreams” and how it links to Provis’s relationships with Estella. The lonesome speaker in “Day-Dreams” resides in Australia and longs to be back in England. The poem relates to Provis in that he has lived a similar experience to the speaker as he's also lived in Australia, but the connection goes further than that. The speaker of the poem longs to be back home in England as they dream of the “little children dear, at dewy play, / Till all [their] heart grows young and glad as they” (“Day-Dreams” 300). The poem draws an association between England and its children, and this parallel can add to the reading of Provis and Estella's relationship. To Provis, Estella is a symbol of England as she was “a little child of whom [he] was exceedingly fond” (Dickens 428). Her youth, the joy she provided to him in the past, and the nostalgia of which he reflects upon her all demonstrate how she is akin to the speaker’s idealization of England. Estella was ultimately taken from Provis by the “young woman, and a jealous woman, and a revengeful woman” he was married to (Dickens 428). His wife then is akin to the speaker's description of Australia, as the speaker remains “wandering lonely, over seas, / at shut of day, in unfamiliar land” (“Day-Dreams” 300). Much like how Australia removes the speaker from the joy and youthfulness associated with England, Provis’ wife threatened to kill Estella out of spite, forcing him to hide himself to save her life (Dickens 429). The speaker closes the poem with the lines, “My sick desire, old friendships fled away / I am much vext with loss” (“Day-Dreams” 300). This loss reflects Provis' ultimate loss of “the child and the child’s mother” as a result (Dickens 429). Much like how the speaker left England, so too does Provis leave Estella and his past behind him. After such a loss, Provis is left wandering overseas, with nothing but bittersweet memories to reflect upon for comfort. “Day-Dreams'' in its longing for the past, sweet, youthful England adds to the longing Provis feels for his child as he is forced to leave his home and settle elsewhere.

Conclusion

The themes of women's gender roles and the past versus present within Chapters XLIX and L of Great Expectations are developed further when read alongside paratextual items from both Harper's Weekly and All the Year Round. Feminine gender roles are presented in the illustration of Miss Havisham on fire by John Mclenan which depicts her as a demonic presence as punishment for inhabiting a space of male power by having wealth. Furthermore feminine gender roles are contended in the advertisement for “Matrimony Made Easy” and how it conflicts with Miss Havisham's loss of identity as she failed to become a wife. The themes of past versus present are developed when read alongside “My Young Remembrance” and how Miss Havisham is a relic of the past versus Pip is a man of the future. These themes are also put into conversation by comparing Provis’ past with Estella to that of the speaker with England in the poem “Day-Dreams”. What these arguments highlight is how the paratexts published alongside Great Expectations can be used as tools to produce a deeper understanding of the themes presented. Future questions to consider are the difference between the modern and historical publishing contexts of Great Expectations and how they shift its reading.

Works Cited

"Day-Dreams." All the Year Round, Chapman & Hall, no. 113, 1861, pp. 300, www.djo.org.uk/all-the-year-round/volume-v/page-300.html.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. Edited by Graham Law and Adrian J. Pennington, Broadview Press, 1998.

McLenan, John. "I Saw Her Running at Me, Shrieking, with a Whirl of Fire Blazing All About Her." Harpers Weekly, Harper & Brothers, vol. 5, no. 234, 1861, pp. 398, ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db= h9k&AN=66832088&site=ehost-live&ppid=divp14.

"My Young Remembrance." All the Year Round, Chapman & Hall, no. 113, 1861, pp. 300-304, www.djo.org.uk/all-the-year-round/volume-v/page-300.html.

T. William & Co. "Matrimony Made Easy." Harpers Weekly, Harper & Brothers, vol. 5, no. 234, 1861, pp. 399, web-s-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/ehost/archiveviewer/archive?vid=1&sid=0dcb4e4d-8589-4a54-8e3a-ca45e0525278%40redis&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#kw=true&acc=false&lpId=divl31&ppId=divp15&twPV=&xOff=108&yOff=2410&zm=5&fs=&rot=0&docMapOpen=true&pageMapOpen=true&AN=66832085&db=h9k.