Part 31

Introduction

When reading Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations in its original context, the influence that the narrative has on readers would no doubt change based on the country in which it is being read. In terms of part 31 – chapters 51 and 52 – readers are met with the distress surrounding Pip’s knowledge of Estella’s parentage and the confirmation of such by Mr. Jaggers. This is then followed by the confrontation of Herbert going abroad for work as well as Pip’s poor treatment of Joe throughout his gentleman status. In All the Year Round published on June 29th, 1861, following the chapters, there is an article called “Friar Bacon” in which the author, highlights the influence of acquiring knowledge. The poem “The Spirits Visit” featured in the same issue regards pain and distress and the haunting nature of those emotions. In Harper’s Weekly however, “Lyrical Lines” appearing prior to the chapters seems to take on a peaceful and happy tone. The advertisements in Harper’s Weekly further proves the hopeful and optimistic tone featured in “Lyrical Lines” by highlighting the heroism of the Union soldiers and encouraging young men to join the Union’s armed forces as implored by Louis Reed-Wood in their article about Civil War propaganda. All the Year Round provides an appropriate tone and context for the chapters featured in the issue. Harper’s Weekly highlights an escapist context of the content within the chapters given America’s pensive attitude during the Civil War. Thus, when reading the chapters in their original contexts, the American readership of the story would differ dramatically from the English readership.

Friar Bacon

In the first passage of Friar Bacon, there is a clear distinction made between the two “ways by which we acquire knowledge,” which is directly related to Pip’s interaction with Mr. Jaggers regarding Estella’s true parentage in chapter 51 (All the Year Round 318). The author states that “…some of us obtain ideas and take interest in studying those objects which are perceptible only by the senses,” (All the Year Round 318). Pip is a direct representative of this idea based solely on how he concludes Estella’s parentage yet, he says “…that the question was not before me in a distinct shape, until it was put before me by a wiser head than my own.” (Dickens 430). The theory of Estella’s parents came to him from both seeing Mr. Jaggers’ maid, Molly, and her resemblance of Estella as well as a story he had heard about Molly’s life. Pip takes interest in something he has deduced from his senses, and it is only objective once it is confirmed by Mr. Jaggers. Therefore, Mr. Jaggers is depicted as the type of person mentioned in Friar Bacon as one that “…[dwells] almost entirely on the nature and powers of the intellect, the qualities of the mind, and ideas derived only from thought and reflection.” (All the Year Round 318). However, Pip is yet again shown here when Mr. Jaggers is caught off guard by Pip’s further knowledge of the situation when Mr. Jaggers’ sudden stop “assured [Pip] that he did not know who the father was.” (Dickens 432). Although Mr. Jaggers holds the “powers of the intellect,” in his confirmation of Pip’s theory, Pip also holds a similar power as he knew even more of the situation than the “head wiser than [his] own.” (Dickens 430). When taking Pip’s understanding of the situation and placing it next to how Mr. Jaggers confirms the truth, Friar Bacon alludes directly to the chapters themselves and the ways in which Jaggers and Pip are represented in works different from the novel itself.

The Spirits Visit

“The Spirits Visit” also featured in the same issue of All the Year Round, explores more of the tonal aspects of chapter 52. The speaker of the poem immediately begins speaking about the emotional toll of the spirit as “He stirs the deep recesses of [their] soul/With passionate pain and longing,” (All the Year Round 323). Pip’s poor treatment of Joe goes unmentioned for most of the novel until chapter 52 in which Pip experiences similar mental duress to the speaker of the poem when he says “The falser he, the truer Joe; the meaner he, the nobler Joe. My heart was deeply and most deservedly humbled…” (Dickens 442). Much like the speaker of the poem, in this instance, Pip is finally coming to the realization of his poor treatment of Joe despite his pure character. The poem’s speaker then goes on to mention their own faults and how that has affected them personally. “I would be strong to aid the weak; to lift/The fallen…Alas! I do not so. Still creepeth in/Some failing of my own.” (All the Year Round 323). Pip is yet again depicted in the poem through his understanding that he only showed “thanklessness to Joe;” (Dickens 442). Lastly, building on the same point, despite all that Joe has been faced with such as “[long]-suffering” and how “[he] never [complains].” (Dickens 442). The speaker of the poem depicts Pip’s representation through the line “I cannot stand alone; yet like a child/Who sees a brother drown,” (All the Year Round 323). Pip understands just how horrible Joe’s life has been; however, it isn’t until now that he realizes that he has left Joe to drown. Not only does this poem show Pip’s realization of his treatment towards Joe in chapter 52 alone, but it also implies his guilt through to the end of the novel and the regrets he holds from becoming a gentleman.

Harper's Weekly Lyrical Lines

The piece “Lyrical Lines” provides a much happier tone in relation to this section of Great Expectations when compared to the pieces featured in All the Year Round. There is an immediate juxtaposition between the subject matter of the novel and “Lyrical Lines.” The speaker says “[may] your happiness be as deep as the sea,/And your heart as light as the foam.” (Harper's Weekly 413). This piece achieves the opposite of the pieces featured next to the novel’s serializations in All the Year Round. In “The Spirits Visit,” the tone only enhances the deep turmoil that Pip is struggling with when facing his poor treatment of his true family. Continuing with the upbeat tone of the piece, the line “they seemed to bear/A magic to cheer and save:” alludes to the sing-song feel of the poem that is also alluded to through the title of the song being “Lyrical Lines” as well as the stylistic elements of the piece. Thus, the discrepancies between the two periodicals begs the question “why is there such a dramatic difference in tone of the pieces featured in All the Year Round as opposed to Harper’s Weekly?” Once examining the advertisements featured in Harper’s Weekly following the chapters, it may become more evident.

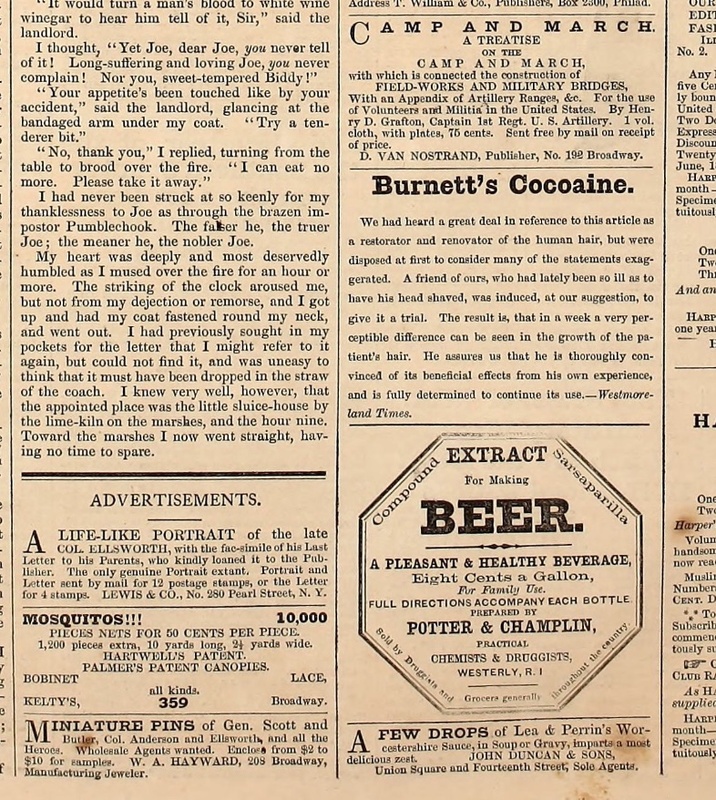

Harper's Weekly Advertisements

Much like the piece “Lyrical Lines,” the advertisements following the chapters are still ignorant of the message being portrayed in the chapters of Great Expectations. The advertisement stating, “A LIFE-LIKE PORTRAIT of the late COL. ELLSWORTH,” shows the distraction from reading for pleasure during the American Civil War (Harper's Weekly 415). There is a strong value placed on war heroes that was meant to be distributed and influence the public to promote the success and importance of Union war heroes. In a slightly different genre of advertisements, sarsaparilla advertised as “EXTRACT For Making BEER” relinquishes the emphasis on the Civil War (Harper's Weekly 415). The remainder of the advertisements go one step further beyond the ignorance of the novel’s content and even ignores the Civil War depicting an escapist view of the struggles that American society was facing at the time. What little emphasis is placed on the war distracts readers from the tone of the novel which is further undermined by the new and exciting products that were available to the public. In the article “’Makers of Loyalty’: recruiting propaganda in the Civil War North.” Louis Reed-Wood mentions that “[during] the Civil War, political leaders, military officers, printers, newspaper publishers…produced thousands of documents and speeches imploring men to join the Union’s armed forces.” (Reed-Wood). In the advertisement “CAMP AND MARCH” the use of the word volunteers indirectly displays the value for enlistment in the Civil War (Harper's Weekly 415). These pieces of propaganda “generally fell within three broad categories. Firstly, they played on men’s patriotism, often arguing they had a duty to the nation.” (Reed-Wood). Much like civilian enlistment in the WWI &II, the idea of volunteerism alludes to the sacrifices that so many men are and will continue to make for their country. Furthermore, the advertisement is indirectly urging young men to join the Union forces as it shows that others have made the same sacrifices, and even more, the advertisement is widely accessible to the public through the growth in widespread media. When considering the tone of both the piece provided before the chapters of Great Expectations and the advertisements appearing after, the only focus of American media of the time was to promote enlistment and heroism of the Union soldiers. Outside of advertisements alone, the periodical aims to distract from the depressing tone of chapters 51 and 52 of the novel.

Conclusion

All the Year Round features secondary pieces alongside chapters 51 and 52 of Great Expectations that further enhances the tone and literary messages that are at play in the novel. On the other hand, Harper’s Weekly does the complete opposite through its direct juxtaposition of tone as well as its emphasis on the Civil War. Due to these distinctions, it is very clear that when reading Great Expectations through Periodicals of All the Year Round, the true message of the narrative would have been captured much more effectively as opposed to Harper’s Weekly. This comes as no surprise when considering America’s preoccupation with the Civil War. Readers of All the Year Round would have been caught up in the disheartening tone of the novel highlighted even more by the same tone of the other pieces featured. On the other hand, readers of Harper’s Weekly would only interact with the upsetting tone of the novel in the chapters alone as the other pieces of the periodical had a completely different tone alongside the light-hearted and heroic mood of the advertisements.

Works Cited

“Harper's Weekly: Bonner, John, 1828-1899: Free Download, Borrow, and

Streaming.” Internet Archive, New York: Harper & Brothers, 1 Jan. 1970,

https://archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv5bonn/page/414/mode/2up?view=theater.

“All the Year Round: Charles Dickens: Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming.”

Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/allyearround05charrich/page/322/mode/2up?view=theater.

Dickens, Charles, et al. Great Expectations. Broadview Press, 1998.

Reed-Wood, Louis. “‘Makers of Loyalty’: Recruiting Propaganda in the Civil War North.” American Nineteenth Century History, vol. 22, no. 1, 7 Mar. 2021, pp. 1–25., https://doi.org/10.1080/14664658.2021.1893481.