Part 32

INTRODUCTION

Harper’s Weekly has particularly vibrant and varying imagery. There is much to learn from these snippets of history that include advertisements and historical illustrations. Yet if a reader examines these images, then they can visualize and interpret Great Expectations as it would have been perceived in the week of 1861. The chapter where Orlick threatens Pip with death in revenge for his job loss would have been exciting and shocking when it came out in a serialized form. The ads and the images that surround this chapter are striking because they mimic Orlick’s aesthetic flaws. The ads coupled with the image of a Texan Ranger would have influenced the reader to consider Orlick’s distressed state as an emblem of the simplistic and religious aesthetic concepts that were endowed and modelled by upper-class ideals.

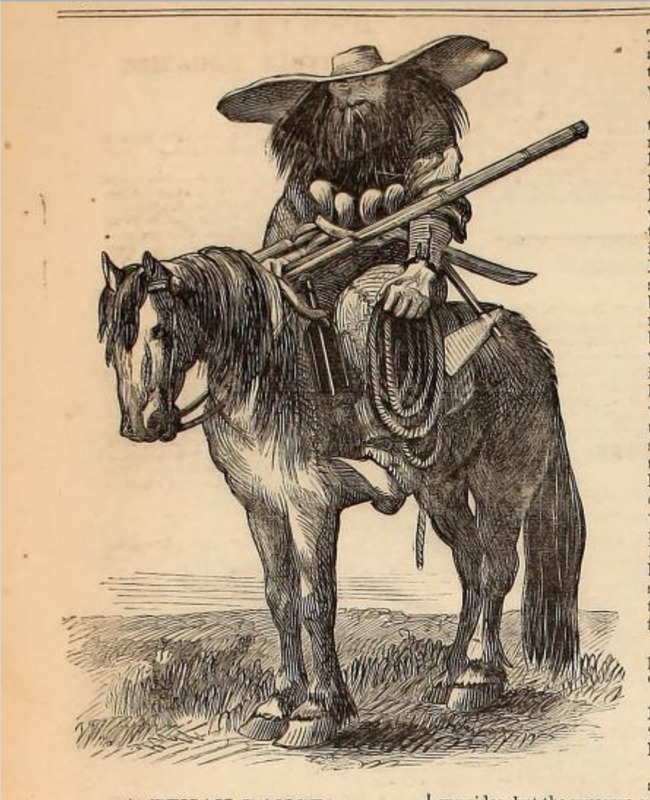

A TEXAN RANGER Caption

The illustration of a Texan Ranger refers to the events of the Civil War in America. I believe this illustration provides viewers with Orlick’s visualized persona to an extent due to the similar reputation of both the Texan Rangers and Orlick. The caption and image depict the costume of the Texan Ranger. According to the artist, they would have had several revolvers, a Tomahawk, and a lasso among other things. This description denotes that the Texan Rangers were an imposing threat. The caption also describes the Texan Rangers as “savage” and this account goes hand in hand with their historically ruthless nature. Nathan A. Jennings's article, “Texan Ranger Auxiliaries” gives a thorough account of a series of battles between Mexican troops and the divisions of Texans that fought against them. The written accounts paired with the actual battle tactics of the Texan Rangers reveal that these men were indeed considered barbaric and ruthless. Jennings indicates that the Rangers had “exceptional lethality” (323) while they lead “’ahead like devils’” (qtd. in Jennings 324). The reader would have known the Texan Ranger’s reputation and this illustration would have pervaded their thoughts throughout the following chapter as they slowly equated Orlick’s ruthless violence to that of the devilish Texan Ranger. Additionally, there is striking hell-like imagery within the chapter. The moon on the moors is “red” and “large” and Pip smells a “sluggish stifling smell” from the lime kilns (Dickens 443). There is plenty of hellish fire imagery here; red is often associated with fire and the smell implies the “stifling” nature of brimstone. The fire imagery continues with Orlick’s lighted candle as he brandishes it at Pip in a “savage taunting” so that Pip had to “[turn] [his] face aside, to save it from the flame” (Dickens 449). The same word, “savage,” is used to describe Orlick’s actions and the appearance of a Texan Ranger. The grizzled and daunting image in Harper’s Weekly would have contributed to the reader’s visualization of Orlick. The imagery of fire too denotes a hell-like punishment that Orlick taunts Pip with. It is as if Pip must pay for his sins against Orlick. The advertisement for an eye balsam extends Orlick’s hellish appearance.

Roman Eye Balsam For Weak and Inflamed Eyes

The advertisement for a “Roman Eye Balsam” coincidentally uses almost the same words that describe Orlick. The advertisement’s diction makes the ailment it describes fixable and therefore a result of one’s own conduct. The word “inflamed” would have allowed the reader to recall the fiery and devil-like reputation of the Texan Ranger and the flame of the previous chapter. The word “weak” may mean any number of things. It could mean weak eyesight or that the eye is physically tired. Yet the connotations of this word are negative and focus on an individual’s inability to perform to a standard. Orlick’s eyes are red and inflamed within the chapter. It is because of Orlick’s drinking that his “eyes [are] red and bloodshot” (Dickens 447). Rather than describing these features as a result of Orlick’s struggles, the description demonizes and makes Orlick vulgar from his over-excessive drinking. In this way, Pip construes Orlick’s appearance as a sign of Orlick’s conduct and not any extraneous factor that undoubtedly contributes to his appearance. Interestingly, later in the passage, Pip equates himself to the alcohol Orlick is drinking. Pip asserts that “every drop” the liquor bottle had “was a drop of [Pip’s] life” and that he may become “vapour” in his death (Dickens 448). Here Pip flips the previous assertion that liquor is affecting Orlick’s state of mind. Instead, Pip refocuses the narrative onto himself and makes Orlick’s state a product of drinking and taking in Pip’s life. This rather demonizes Pip. If Pip’s life is the reason Orlick looks so frightening, then this rather incriminates Pip’s character as it does Orlick. In this way, Pip and Orlick become synonymous under the same imagery in this scene. The advertisement begins to illuminate Orlick and Pip's effect on one another through food and drink motifs.

TO ASSIST DIGESTION

Strikingly, there is also an advertisement for Worcestershire sauce that supposedly helps with digestion. The ad details that the sauce also gives “tone” to the stomach. The ad is for an audience with a need for an aesthetic look as well as relief for an ailment. By association, the advertisement hints that a bloated and round stomach is undesirable. Orlick references food several times in the passage specifically by relating Pip to it. After Orlick’s “mouth water[s]” for Pip he exclaims that he “won’t have a rag of [Pip], [he] won’t have a bone of [Pip], left on earth. [He’ll] put [Pip’s] body in the kiln” (Dickens 446). The diction in this sentence is very reminiscent of a meal. Orlick wants to devour every part of Pip so that there will be no evidence of him “left on earth.” He also mentions a kiln as if he wishes to cook Pip’s “body.” The fact that Orlick threatens that he could eat the entirety of Pip’s body implies gluttony and over-excess. The reader’s mind may make a connection between a large meal and a bloated and round stomach. This advertisement’s placement would have equated Orlick to a grotesque and unaesthetic being. Considering the nature of Orlick’s hypothetical heavy meal, it is not hard to believe that readers would have assessed themselves for bloating or even felt bloated just from the vivid description of Pip as both food and drink. Orlick’s ailments seem to be associated with Pip’s influence. Additionally, Orlick identifies Pip as a “wolf” several times throughout the chapter (Dickens 445-49). Yet judging by Pip’s descriptions of Orlick’s hunger for his death, this is ironic. However, Pip’s identification as a wolf further equates him to the cause of Orlick’s grief and therefore makes Pip the corrupt influence that then taints Orlick. Orlick’s accusations against Pip imply this causal relationship (Dickens 446). Yet unless these advertisements are taken into account, the reader glances over this relationship between Pip and Orlick.

Jennings discusses that there was a similar dynamic between both the Mexican troops and the Texan Rangers in the Civil War. Mexican troops used intense guerilla warfare that only the Texan Rangers with their “irregular fighting” style could contend with (Jennings 327). Yet Jennings only slightly alludes to the fact that what was thought to be corrupt behavior within the second division of Texan Rangers was the same fighting style that Mexican troops used (327). Jennings does not fully stress that it was because the troops othered the division of Mexicans that the emulation of this fighting style was considered devilish. The fact that Pip is described as the food and drink that degrades Orlick’s persona is similar to the Texan Rangers taking Mexican-style guerilla warfare. Pip inadvertently narrates how he has corrupted Orlick through his upper-class ideals. The “Loveliness” advertisement clarifies these ideals.

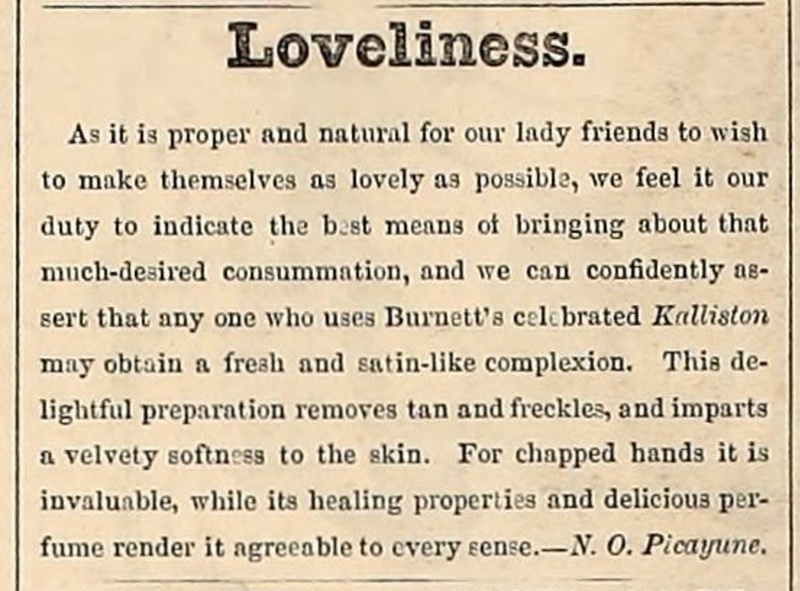

Loveliness

The advertisement for a “Loveliness” preparation promotes a direct contrast between what the consumer is supposed to be and what they should not be. Although the ad is targeted at women, the ad merely illustrates the belief that women were the ones worried about satin skin rather than satin skin not being desirable for men. The ad indicates that the preparation removes tan and freckles both of which Orlick would undoubtedly have from the labour intensity of his previous work. Additionally, the ad mentions that the preparation could cure chapped hands. Orlick’s work with Joe as a blacksmith would undoubtedly imply his hands were not smooth. These characteristics are in stark contrast to Orlick. The contrast is so blatant that the “Loveliness” ad becomes stereotypically angelic; Orlick is hellish whereas the word “loveliness” and the implication that the preparation gives the user a lighter skin tone would have imparted a sense of purity to Victorian readers. This would have further degraded Orlick in the minds of the original readers of the text. The ad also contrasts with the image of the Texan Ranger. Jennings asserts that Rangers were thought to be “’devils incarnate’” (qtd. in Jennings 329). The distinctions between angel and devil mark the problematic simplicity of both desirable and undesirable physical characteristics.

CONCLUSION

The original context of this Great Expectations chapter contained sufficient advertisements and images that undoubtedly would have clouded the reader's mind. Particularly, the ads and images all coincide with Orlick’s representation. The Civil War illustration, eye balsam, Worcestershire sauce, and cream all represent Orlick as an abomination and an aesthetic flaw. Yet with a combined reading of both the text and the context surrounding it, the reader would have noted that aesthetic flaws are devil-like. The ads imply that aesthetics categorized people into devilish and angelic, which denotes that Victorians craved simplicity in this regard. Yet most striking is the implication that this may be contagious. The mixture of both context and Pip’s effect on Orlick’s behaviors may showcase that Dickens wished to flip typical class disgust on its head.

WORKS CITED

“A TEXAN RANGER.” Harper’s Weekly, vol. 5, no. 236, 1861, pp. 430, Internet Archive (digital), https://archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv5bonn/page/430/mode/2up. Accessed 6 April 2023.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations, edited by Graham Law and Adrian J. Pinnington, Broadview Press, 1998.

Jennings, Nathan A. “Texan Ranger Auxiliaries: Double-Edged Sword of the Campaign for Northern Mexico, 1846-1848.” Small Wars and Insurgencies, vol. 26, no. 2, 2015, pp. 313-34, Taylor & Francis Online, https://www-tandfonline- com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/doi/full/10.1080/09592318.2015.1007560. Accessed 6 April 2023.

John Duncan & Sons. "TO ASSIST DIGESTION." Harper's Weekly, vol. 5, no. 236, 1861, pp. 431, Internet Archive (digital), https://archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv5bonn/page/430/mode/2up. Accessed 6 April 2023.

Picayune, N.O. "Loveliness." Harper's Weekly, vol. 5, no. 236, 1861, pp. 431, Internet Archive (digital), https://archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv5bonn/page/430/mode/2up. Accessed 6 April 2023.

"Roman Eye Balsam For Weak and Inflamed Eyes." Harper's Weekly, vol. 5, no. 236, 1861, pp. 431, Internet Archive (digital), https://archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv5bonn/page/430/mode/2up. Accessed 6 April 2023.