Part 33

Magwitch as a Slave Narrative

Sophie Wright

Introduction

Charles Dickens’s novel Great Expectations explores themes of wealth, poverty, and enslavement. In her book, The Ideas in Things: Fugitive Meaning in the Victorian Novel, Elaine Freedgood explores themes of enslavement and colonization in the chapter “Realism, Fetishism, and Genocide: Negro Head Tobacco in and around Great Expectations.” Freedgood explains that representations of enslavement are present in many characters throughout the novel; both Pip and Joe are originally enslaved to Mrs. Joe, who controls the men in her household with physical violence, Estella enslaves Pip emotionally, and Estella is enslaved to Mrs. Havisham’s will (Freedgood 97). However, the most apparent representation of enslavement is through the character Magwitch. Volume 5, Issue 237 of Harper’s Weekly, which came out July 13, 1861, includes Chapter 54 of the novel, in which Pip attempts to sneak Magwitch out of England; however, British customs agents catch them before Magwitch can reach freedom (Dickens 465). Magwitch then endures an epic underwater battle with Compeyson; Compeyson dies in the battle, and Magwitch survives with fatal wounds and is sent back to prison (Dickens 466). This chapter depicts the climax of Magwitch’s story, in which the escaped convict is recaptured, reminiscent of the tropes of a slave narrative. The publication surrounds this chapter with news articles concerning the American Civil War, which had begun two months prior in April. Harper’s Weekly establishes Magwitch’s story as a slave narrative by surrounding the chapter of his arrest and recapture with references to the American Civil War and Slave Trade. Dickens portrays a white European character as enslaved to evoke sympathy for the character and those enslaved in America.

Qualities of the 'Slave Narrative'

Firstly, what is a slave narrative? Julia Sun-Joo Lee explores slave narrative and fugitive plots in her book The American Slave Narrative and the Victorian Novel. Lee explains that the slave narrative “is attached to experiences of suffering and violence, of familial and natal alienation, of unfreedom and terror, of the Helegian struggle between enslaver and slave… Above all, it is affiliated with pursuit, with geographic instability, with homelessness and fear of capture” (Lee 117). Magwitch’s story relates to these tropes, as he first encounters Pip on the marshes, running away from prison “with a great iron on his leg” (Dickens 40). He escapes to Australia to find his fortune for Pip. Magwitch’s initial escape is reminiscent of the escape of an enslaved person in America, running on foot, still chained through rough terrain.

Furthermore, Magwitch relates to Pip that he has no family that he can remember, “I know’d my name to be Magwitch, christen’d Abel. How did I know it? Much as the birds’ names in the hedges to be chaffinch, sparrer, thrush” (Dickens 370). Magwitch’s love for Pip stems from an absence of family; due to this absence, he creates one of his own through Pip, “lookee here, Pip. I’m your second father. You’re my son.” (Dickens 346). Magwitch’s pursuit of familial connection mirrors the struggles of enslaved African Americans who were separated from family by enslavers. Lee also explains that slave narrative escapes often occur in swamps, rivers and the sea and “escape vehicles are the ship and the train” (Lee 117). Magwitch’s first escape, where he meets Pip, is through the swamp and marshes, and his final attempt at freedom is by boat. However, despite Pip and Magwitch’s best efforts, he is recaptured (Dickens 466).

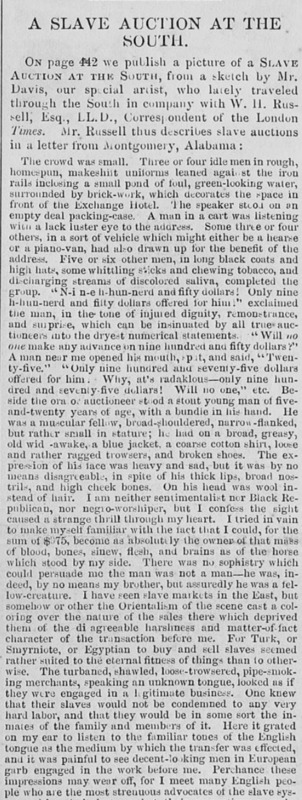

Eurocentric Reactions to Enslavement

Magwitch’s character and plot coincide with the themes related to the slave narrative; however, Magwitch is still a white European character. Why did Dickens portray a slave narrative through the character of a white European man instead of a Black one? Freegood claims it would be “shocking to find the story of the oppression and murder of Aboriginal people in a Victorian novel” (Freegood 98). Harper’s Weekly’s article “A Slave Auction At The South” by W. H. Russell illuminates why readers during this period would react this way towards an Indigenous or Black slave narrative and not a white one. In Russell’s description, he notes how the auction made him feel. He explains that he is not a “sentimentalist nor Black Republican,” but “the sight caused a strange thrill through [his] heart” (Harper’s 447). Russell continues in his description to explain that he has seen slave auctions in the East, that “for Turk, or Smyrniote, or Egyptian to buy and sell slaves seemed rather suited to the external fitness of things” and “the turbaned, shawled, loose-trowsered, pipe-smoking merchants, speaking an unknown tongue, looked as if they were engaging in legitimate business.” (Harper’s 447). In Russell's explanation, he embarks on a racist tangent about how those in the East can be “legitimately” enslaved. However, it was painful for Russell to see a slave auction take place in America, listening “to the familiar tones of the English tongue as the medium by which the transfer was effected,” seeing the enslaved, “decent-looking men in European garb” being sold in this auction. It is interesting how Russell is not triggered by the enslavement, oppression, and abuse of the enslaved, but the Europeanness of the enslaved sparks his emotional response. The wrongness stems from the belief in Eurocentric superiority. Meanwhile, he assures the reader that it is normal for people dressed in turbans, shawls, and loose trousers to take part in the slave trade. Therefore, did Dickens portray this slave narrative through a white character to evoke sympathy in the reader? When Magwitch is recaptured by the British customs officers is a tragic end to his failed grand escape (Dickens 466). Both Pip and the reader are heartbroken for the man who had tried to provide for Pip. The crown assumes authority over his wealth as well as his freedom, leaving Pip a poor man again (Dickens 468). Using this racist ideology that Europeans were not meant to participate in the slave trade or be enslaved, Dickens highlights European hypocrisy by evoking sympathy for a white character portraying a Black enslaved narrative. During the nineteenth century, would Dickens have been able to evoke sympathy for Magwitch had he been an escaped enslaved Black man?

References to Enslavement and Oppression in the Colonies

Since it would be “shocking” to include a story of the murder and oppression of a Black or Indigenous character in a Victorian novel, Dickens instead uses references to murder and oppression in the colonies. Magwitch travels to Australia to make his fortune, a colony of the British Empire. Magwitch finds fortune in the land which Britain has enslaved and murdered has murdered many of the Indigenous. When it is revealed that Magwitch is Pip’s patron, Magwitch pulls out a “handful of loose tobacco of the kind that is called Negro-head” (Dickens 355). By referencing tobacco, Dickens would prompt images of enslaved Black and Indigenous peoples in the reader's mind because during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, “Africans, African Americans, and Native Americans” were used as “logo” material in tobacco advertising and brand designs” (Freedgood 93). Through these references, Dickens related Magwitch to the enslaved Black and Indigenous peoples of the colonies, connecting his character to their stories and themes without making him a Black or Indigenous Character.

Motivations for Civil War

Through the articles presented in Harper’s Weekly in its July 13th publication, Dickens’ reason for making Magwitch a white character is evident through the still racist and conflicting perspectives on enslavement in America.

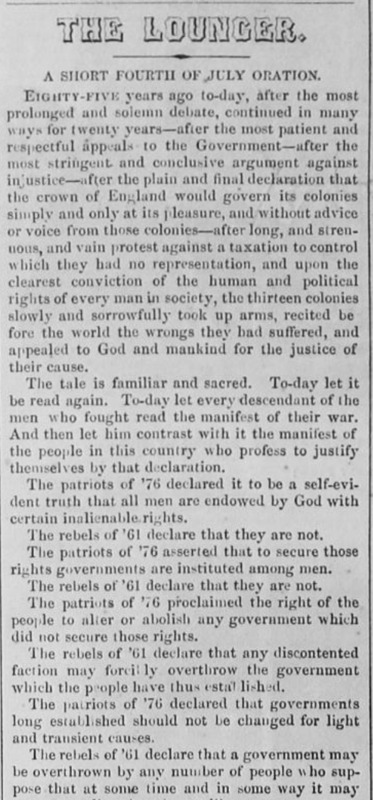

The Lounger presents “A Short Fourth of July Oration,” a seemingly motivating call for all Americans to unite against the Rebels of the Civil War, advocating for their right to participate in enslavement. The Lounger states that with America’s independence in 1776, it was decided that “all men are endowed by God with certain inalienable rights” (Harper’s 434), thus, insinuating that all men were born free and enslavement is against their rights as men. However, despite the call to dismantle enslavement, there are still racist views in Harper’s Weekly.

Erasure of Individual Identities of Those Enslaved

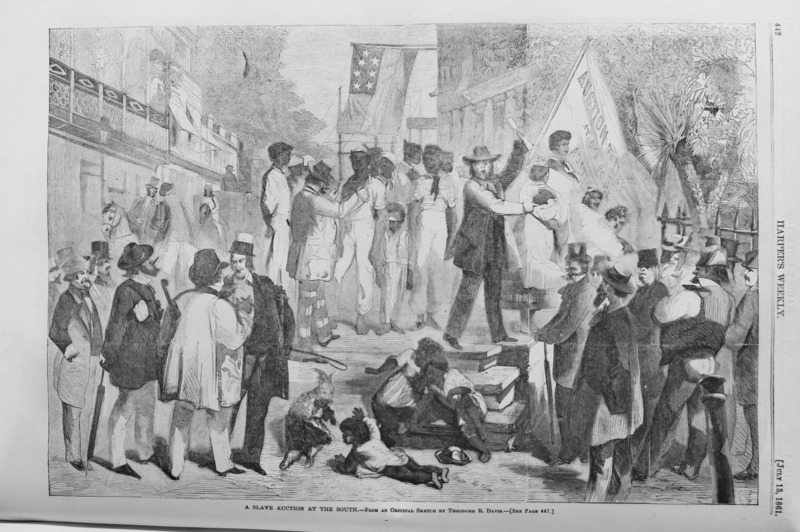

The perspective presented above by Russell is accompanied by a sketch again entitled “A Slave Auction At The South” by Theodore R. Davis. This picture depicts a group of Black enslaved people standing on a stage surrounded by white men below them. What is particularly interesting is that Davis created many white men’s sketches with detailed faces and clothing. In contrast, the topic of the sketch, the enslaved, is a blurry collection with no distinct features or identifiable faces. By neglecting to portray the enslaved as individuals, Davis dehumanizes the enslaved and amasses them into one group, stripping away any individualism or identity

England's Perspective

Since Harper’s Weekly is an American publication, and Dickens and Magwitch are both British, it is important to look at the British perspective on the Civil War in America. “A Word From England” by an unnamed source explains that through this strife between the North and South, England will “strive her utmost, as it natural, to keep neutral” and any attempt at England’s interference “would almost create a civil war here too” (Harper’s 435). Thus, Dicken’s critique of enslavement could have been received well by some and poorly by others. Similar to the United States, it seems England was divided on their position of enslavement as well.

When Magwitch reveals to Pip that he is his patron, Pip is initially disgusted with him “Every hour so increased my abhorrence of him” (Dickens 362). However, once Magwitch is arrested in Chapter 54, Pip admits that he cares for Magwitch after his arrest stating, “my repugnance to him had all melted away, and in the hunted wounded shackled creature who held my hand in his, I only saw a man who had meant to be my benefactor, and who had felt affectionately, gratefully, and generously towards me… I only saw in him a much better man than I had been to Joe” (Dickens 467). Magwitch and Compeyson’s final battle is a struggle between Enslaver and enslaved person, where Magwitch was enslaved to Compeyson’s schemes. Magwitch is freed from Compeyson when he drowns, although he loses his freedom again as he swims back to the boat. Pip explains, “I saw it to be Magwitch, swimming, but not swimming freely. He was taken on board, and instantly manacled at the wrists and ankles” (Dickens 466). The conclusion of chapter 54 is a heartbreaking separation of Pip and Magwitch. The two had found a family in each other and were now separated again, reinstating Magwitch as enslaved.

Conclusion

In conclusion, reading Great Expectations Chapter 54 in the context of its original publication in Harper’s Weekly further cement Magwitch’s character and story as a slave narrative. In collaboration with Elaine Freedgood’s chapter “Realism, Fetishism, and Genocide: Negro Head Tobacco in and around Great Expectations” and Julia Sun-Joo Lee's exploration of fugitive and enslaved narrative in The American Slave Narrative and the Victorian Novel, Magwitch’s character is proven to parallel the slave narrative. The articles and sketches surrounding the chapter in Harper’s Weekly highlight the historical context of the period and explain why Charles Dickens chose to depict Magwitch as a white character in an enslavement narrative instead of a Black one. Due to the continued prejudices of the period, seen throughout the articles presented in Harper’s Weekly, Dickens creates Magwitch, a white character in a slave narrative, to evoke sympathy for those enslaved and highlight the Eurocentric hypocrisy when considering race and enslavement.

Works Cited

"A Short Fourth of July Oration." The Lounger. Harper's Weekly, vol.5, no. 237, 13 July 1861, p.434. EBSCOhost. https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=h9k&AN=67082956&site=ehost-live&kw=true&acc=false&lpId=divl24&ppId=divp2&twPV=&xOff=250&yOff=396&zm=3&fs=&rot=0&docMapOpen=true&pageMapOpen=true

"A Word From England." Harper's Weekly, vol.5 no. 237, 13 July 1861, p. 445. EBSCOhost. https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=h9k&AN=67082956&site=ehost-live&kw=true&acc=false&lpId=divl24&ppId=divp3&twPV=&xOff=250&yOff=396&zm=3&fs=&rot=0&docMapOpen=true&pageMapOpen=true

Davis, Theodore R. "A Slave Auction At The South." Harper's Weekly, 13, July. 1861, p.442. EBSCOhost. https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=h9k&AN=67082956&site=ehost-live&kw=true&acc=false&lpId=divl18&ppId=divp10&twPV=&xOff=0&yOff=0&zm=fit&fs=&rot=0&docMapOpen=true&pageMapOpen=true

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. Edited by Graham Law and Adrian J. Pinnington, Broadview Press, 1998.

Freedgood, Elaine. The Ideas in Things : Fugitive Meaning in the Victorian Novel. University of Chicago Press, 2006.

Lee, Julia Sun-Joo. “Fugitive Plots in Great Expectations.” The American Slave Narrative and the Victorian Novel, Oxford University Press, 2010, https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195390322.003.0005.

Russell, W.H. "A Slave Auction At The South." Harper's Weekly, vol.5, no.237, 13 July 1861, p.447. EBSCOhost. https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=h9k&AN=67082956&site=ehost-live&kw=true&acc=false&lpId=divl24&ppId=divp15&twPV=&xOff=250&yOff=396&zm=3&fs=&rot=0&docMapOpen=true&pageMapOpen=true