Part 34

Introduction

The publication of Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations in the American magazine Harper’s Weekly was formatted in a way which imbued the story with American ideals. The accompanying illustrations, advertisements, and other stories in the magazine affected the way in which readers perceived the text by highlighting certain aspects of the story and underplaying the parts that did not appeal to the American audience. Nancy West and Leigh Dillard focus on the work of John McLenan’s illustrations and the way in which he guides the audience’s interpretation of the novel (West and Dillard 197). I will be furthering their analysis by focusing on the ways in which the accompanying advertisements, illustrations, and stories aided American audiences in laying a claim to Dickens and encouraged readers to view the story from a romantic lens that also promoted support for the Northern states during the American Civil War. I will be focusing on the July 20th 1861 publication of Harper’s Weekly which contains Chapters LIV and LV. These chapters follow the aftermath of Compeyson and Magwitch’s confrontation, as Pip partakes in Wemmick’s wedding and witnesses Magwitch’s passing. Paratextual elements that appeared with each installment “played a substantial role in both Americanizing the novel and romanticizing it” (West and Dillard 202). Isolating these two chapters gives the reader the impression that Dickens’ ultimate goal is the romantic union of Pip and Estella. Not only did Harper’s Weekly emphasize the importance of a union between Pip and Estella, they emphasized the union of the country in the time of the American Civil War.

During the serialization of Great Expectations, Harper’s Weekly “settled into a patriotic identity and role” (West and Dillard 201). As a result, Great Expectations “became increasingly woven into a discourse of national pride” (West and Dillard 201-202). The magazine’s preoccupation with a union as the ultimate goal of Dickens’ story is a result of the Civil War dividing the country at the time of the publication. The American Civil War was the “culmination of the struggle” between the Northern States, known as the Union, and the Southern States, known as the Confederate, over their conflicting ideas regarding the abolishment of slavery (Weber and Hassler). Although Dickens was relatively impartial to this period of American politics (Waller 536), Harper’s Weekly utilized intertextual references alongside Great Expectations to advocate for a pro-North, and therefore pro-Union stance. The July 20th 1861 issue was published in the first few months of the years-long war, so information surrounding the war populated the majority of its pages. Accompanying textual elements “would have directly engaged [the reader’s] senses, no doubt coloring, and, to a large extent, Americanizing -- the way in which Great Expectations was absorbed through the mind’s eye” (West and Dillard 197). By aligning Dickens with the North, Harper’s Weekly attempted to “unite disparate audience members through the act of reading over an extended period of time” (West and Dillard 197).

Alstyne White

Magwitch’s death ends Chapter LV, and immediately after Pip’s farewell, Harper’s Weekly placed a short, somber poem about a grandmother who is frozen in time as she experiences the loss of her son and her grandson simultaneously. The old woman holds on to a sword with “a loving clasp,” as it is a reminder of her deceased son. This line calls back to Magwitch holding Pip’s hand in a loving clasp (Dickens 480), and carries the same relationship between parent and child. The son dropped the sword in battle, but by holding onto the sword, the grandmother is holding onto her son. These sentiments echo the moment shared between Pip and Magwitch. Pip reminds Magwitch that he “had a child once” whom Magwitch had “loved and lost” (Dickens 480). The grandmother is caught between the past and the present as she notes the strong resemblance between her grandson and his deceased father. The grandson asks for her blessing as he prepares to join the war effort and follow his father’s footsteps. Similarly, Pip says that there are “no better words” that he could impart onto Magwitch than a prayer of forgiveness from the Lord (Dickens 481). Knowing that there is no avoiding Death, both Pip and Grandmother White impart a final prayer to bless their loved ones as they depart from this life. Even though there is a strong fascination with the war, Harper’s Weekly does not glorify the war, but understands that it is causing unnecessary casualties. Placing this poem immediately after Magwitch’s death intensifies Dickens’ sentiments and connects the text to a scene that hits close to home for American readers.

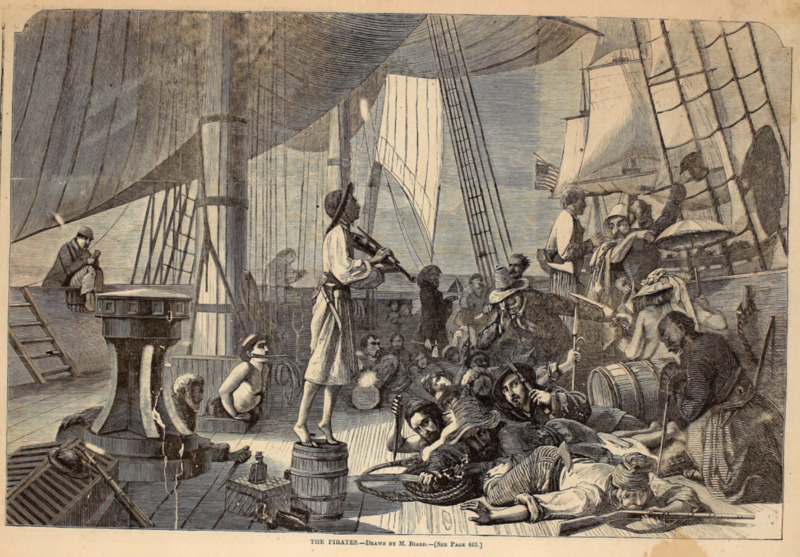

Beside “Alstyne White” is an informative section that calls the reader to turn back a few pages to view an engraving of The Pirates, a painting by Francois Biard. This column says that the painting “will be timely just now.” This statement refers to the chapters of Great Expectations that were published in this issue, as well as to the political climate at the time. The painting depicts a nefarious crew that are “artfully luring” an unseen victim “into their clutches.” One of the prominent figures in this crew of villains is described as a “well-dressed gentleman.” Although they were guilty of the same crimes, Compeyson was considered a gentleman, and was not convicted as heavily as Magwitch (374). Furthermore, Wemmick describes Compeyson as a “very clever man” for his skill at deception (472). The setting of the pirate ship also calls to the “prison-ship from which [Magwitch and Compeyson] had once escaped” (468). Like the pirates in the painting, Compeyson lured Magwitch into his clutches by dressing as a respectable, trustworthy man. This painting speaks not only to the deceptive nature of one’s appearance and the disconnect between appearance and morality, but also to the villainous portrayal of the South. The tropical climate in the painting positions these Pirates as coming from the South. By asking the readers to turn back to the painting instead of placing this information with the painting, it calls readers to view the image again when they have Great Expectations fresh in their mind and can make connections to the text.

Gardiner's Compound Rheumatic and Neuralgic

Gardiner’s Compound, which is advertised as a “certain cure,” is both rheumatic and neuralgic, meaning that it performs a dual action which heals the body. The central figure in this image is a cherub which attempts to heal the woman. Like Magwitch, the woman appears to be ill and dying. Magwitch “lay in prison very ill” (476) and was depicted throughout the chapter as becoming “slowly weaker and worse” (478). The cherub and the little boy who support the woman and deliver the cure to her are reminiscent of Pip. During Magwitch’s trial, Magwitch finds solace in believing that Pip had seen “some small redeeming touch in him, even so long ago as when [Pip] was a little child” (476). The little boy offering the cure to the woman looks like a younger version of the cherub that is holding the woman up. Both as a child and as a man, Pip supports Magwitch in difficult times. The religious imagery also calls back to Pip’s cry that God may forgive Magwitch (481). Furthermore, the woman in this advertisement can be seen as a symbol for the motherland; a mother weakened while surrounded by people who are divided. A compound, otherwise known as a union, is a certain cure which can heal the divided body of the country.

Matrimony made Easy

One of the bolded advertisements in this issue guarantees that matrimony is accessible to all. In Chapter LIV, Herbert says that as soon as Clara’s father passes away, the pair will “walk quietly into the nearest church” to finally be wed (Dickens 471). Shortly after this declaration, Pip ends up partaking in Wemmick’s nuptials (Dickens 474). The joy from these scenes juxtaposes the somber events that follow as Pip witnesses Magwitch’s passing in the subsequent chapter. After the scene in which Pip reveals Estella’s identity to Magwitch and declares his love for her (480), readers would have seen this bolded advertisement on the same page and rooted for Pip’s happy ending through a union of his own. The advertisement states that “irrespective of age or appearance,” one can find a partner. This line encourages readers to believe that it is not too late for Pip to marry Estella. Even though much time has passed and Pip no longer possesses the superficial qualities that define a gentleman, this advertised piece suggests that there is a method “which can not fail.” Although this ad implies that class differences are irrelevant to love, people will only have access to this knowledge for a fee. The work is “free for 25 cents.” Although it advertises itself as accessible, it still requires some amount of wealth. Matrimony will be easy for those who have enough wealth to access privileged knowledge. This advertisement frames marriages, and by extension unions, as the easy choice which will bring happiness. By supporting unions through marriage, and by extension supporting the Union in the war, the alternative of death can be avoided.

Wedding Cards

A notable advertisement in this issue states the two objectives of Harper’s Weekly in promoting Dickens’ piece to an American audience; the promotion of love and union. The two wedding cards call back to the weddings mentioned in Chapter LIV. The first card with two names reminds readers of Wemmick and Miss Skiffins (474). The second card with only one name reminds readers of Herbert’s plans for marriage with Clara, who is named but does not physically appear in the chapter (471). In conjunction with the advertisement for “Matrimony made Easy,” these wedding cards advocate for Pip’s marriage to Estella in later chapters. At the time of this issue’s publication, readers had hope for Pip’s marriage to Estella and for the Union to triumph.

Conclusion

Dickens was notably reluctant to speak on the politics of the American civil war, but through the paratextual elements provided by Harper’s Weekly, Dickens’ Great Expectations became a vehicle for cultivating American sentiments, thereby advocating for the union of the characters, and for the country. By placing the poem “Alstyne White” immediately after Magwitch’s passing, Harper’s Weekly translates grief from one passage into the next. According to Gardiner’s Compound, the cure for grief is ultimately love through union. Advertisements for wedding cards and for a work called “Matrimony Made Easy” emphasized the romantic aspects of Chapters LIV and LV while maintaining an undercurrent of pro-Union stance. Biard’s painting further develops pro-Union sentiment by positioning the nefarious Compeyson with the devious South. All of these advertisements, illustrations, and stories which are peripheral to the text allowed Harper’s Weekly to Americanize Great Expectations and promote the romantic aspects of unions while subtly reinforcing support for the Union during the Civil War.

Works Cited

Biard, Francois. "The Pirates." Harper's Weekly, vol. 5, no. 238, 20 Jul 1861, p. 463. Internet Archive. archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv5bonn/page/463/mode/1up?view=theater.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. Edited by Graham Law and Adrian J. Pinnington, Broadview Press. 1998.

E.B. "Alstyne White." Harper's Weekly, vol. 5, no. 238, 20 Jul 1861, p. 463. Internet Archive. archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv5bonn/page/463/mode/1up?view=theater.

Everdell. "Wedding Cards." Harper's Weekly, vol. 5, no. 238, 20 Jul 1861, p. 463. Internet Archive. archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv5bonn/page/463/mode/1up?view=theater.

"Gardiner's Compound Rheumatic and Neuralgic." Harper's Weekly, vol. 5, no. 238, 20 Jul 1861, p. 463. Internet Archive. archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv5bonn/page/463/mode/1up?view=theater.

T. William & Co. "Matrimony made Easy." Harper's Weekly, vol. 5, no. 238, 20 Jul 1861, p. 463. Internet Archive. archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv5bonn/page/463/mode/1up?view=theater.

"The Pirates." Harper's Weekly, vol. 5, no. 238, 20 Jul 1861, p. 459. Internet Archive. archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv5bonn/page/463/mode/1up?view=theater.

Waller, John O. "Charles Dickens and the American Civil War." Studies in Philology, vol. 57, 1960, pp. 535-548. ProQuest, ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/charles-dickens-american-civil-war/docview/1291691379/se-2.

Weber, Jennifer L, and Warren W Hassler. “American Civil War”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 6 Apr 2023, www.britannica.com/event/American-Civil-War.

West, Nancy, and Leigh Dillard. “Miss Havisham on the Home Front: Dickens, Literary Nationalism, and Harper’s Weekly.” Nineteenth Century Studies, vol. 26, 2012, pp. 195–218. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mzh&AN=2019391975&site=ehost-live.