Part 36

Introduction

In the true fashion of a coming-of-age bildungsroman, Charles Dickens’ novel Great Expectations concludes with main character Pip achieving a newfound sense of enlightenment and maturity. Through Pip’s ruminations, the second last chapter discusses what it means to possess a moral character in Victorian-era Britain. As outlined in the chapter, Pip moves to Egypt with his closest friend Herbert, and spends a year working to pay off his debts. As his explanation comes to a close, Pip gives the following summary of his time away:

We were not in a grand way of business, but we had a good name, and worked for our profits. We owed so much to Herbert’s ever cheerful industry and readiness, that I often wondered how I had conceived the old idea of his inaptitude, until I was one day enlightened by the reflection, that perhaps the inaptitude had never been in him at all, but had been in me. (499)

In an evaluation of Dickens’ employment of the bildungsroman form, Florian Schweizer characterizes this chapter as the culmination of Pip’s psychological journey. Citing the same excerpt, Schweiler states that Pip’s “actual formation comes through the realization and acknowledgement of his errors and delusions about his own character” (145-146). So, this section can be read as Dickens’ ultimate conclusion on what constitutes a good moral character in his contemporary era. Pip connects Herbert’s virtues to his economic capabilities. Herbert is apt because he is cheerful, industrious, and consistently ready to do hard work, and it is these characteristics that allow him to create a successful business and live a fulfilling life. As Lauren Goodlad outlines, Victorian Britain’s industrial revolution provided a terrain in which

sociology provided the salient disciplinary framework, materialism and idealism proffered philosophical alternatives, and Fabian ideals of state efficiency vied with the network of voluntary associations preferred by the Charity Organization Society (152).

In essence, a sense of morality was beginning to fuse with the frameworks laid out by industry. This was only natural, as conceptions of human character align with social frameworks, and under industrialization, urban spaces in Victorian-era Britain were characterized by factory life. So, “turn-of-the-century sociology regarded character as a set of features which … was amenable to social conditioning on behalf of the public good” (153). Societal structure could influence the individual, and those individuals who proffered support for exploitative structures were construed by the likes of Dickens as possessing amoral characters.

These chapters of Great Expectations were first serialized in the 119th edition of Dickens’ publication All the Year Round. Dickens’ novel was not the only piece of work in this edition that reflected Goodlad’s description of Victorian morality. This means that readers of All the Year Round were exposed to and, likely, influenced by the publication’s cohesive stance.

Mastery = Morality in "Drift: Ancient Quacks":

Drift: Ancient Quacks

An article detailing how a decree condemning false medical practitioners released during Henry V's reign is relavent in 1861

Death was widespread and common in the Victorian era. As a result, many individuals saw to impersonate medical practitioners without a licence. A doctor was a godsend, a way out from a seeming inevitability. They were in demand, thus making death a business one could profit from. This article condemns those false practitioners by citing a decree from Henry V’s reign, stating that “it might serve as a protest in our own time” (443). The decree is written in older English, but essentially says that no man or woman should perform a medical feat without a licence (443). It reasons that no man slated to die should die for wanting help, and no man should perish by the un-coming of a doctor (443). As well, the decree states that false doctors should want to follow it, because doing so is a way of attending to their souls and bodies—essentially, it characterizes their actions as sinful and unvirtuous (443). These words come from a 14th-century perspective, and are translated to Dickens’ contemporary era through the article’s author.

This author does not speak much of character or virtue directly. Instead, they state that false doctors should be punished because they are “practitoners of the basest art of swindling,” and that the 14th-century judicial system was “empowered to punish such [individuals] as [they] practise without having proved themselves before the masters of [the medical] art” (443, 444). The 19th-century author positions themselves in agreement with the 14th-century decree. So, we can assume that they also believe that by stopping their false practice, these swindlers will save their souls. A modern-day viewer would likely assume that the primary sin of false medical practice is the death it causes, not the loss of substantial funds. Yet, the 19th-century voice seems to think the opposite. I caution you not to think this voice depraved, but to instead return to Goodlad’s outline of Victorian morality. Death was far more prevalent in the Victorian-era, and medical advances were paltry. So, in the likely event that the efforts of a licensed surgeon failed, the victim could take solace in knowing that their family was not left destitute. As well, as Goodlad outlines, Victorian morality was swiftly growing synonymous with good business practices (153). Many deaths and atrocities were caused by exploitative economic systems, and as a result “commercial and industrial culture [was regarded] as a drain on or threat to moral character” (Goodlad 137). “Drift”’s seemingly odd focus on theft when discussing false medical practice actually reflects the Victorian fusion of morality and industrial virtue.

Good People Need Not Be People- “A Night in the Jungle”:

This article tells a story of four gentlemen who embark on a nighttime inspection of the London Zoological Gardens. The author states that the forest resembled “some Indian jungle or Australian forest” (445). Upon their entry, the gentlemen “found themselves suddenly transported from Central London to Central Africa” (445). The text parallels their excursion to that of a colonial explorer in one of the aforementioned regions. Along their tumultuous journey through the leafy wilds, the gentlemen come across some fish. The animals are described as possessing a “detestable wakefulness” in the nighttime hours, which are intended for sleeping (447). Immediately following the fish encounter, the adventurers come across some monkeys, and the author states that,

It was refreshing, after the … fish, to find in the monkey country, which lay next in the route of our travellers, that the inhabitants were an orderly and well-conducted race, and were taking their rest in a natural way, at a natural time … more than a dozen of these right-minded animals were sitting in a row (447)

This article continues to show Goodlad’s conception of Victorian morality. The monkeys are deemed “right-minded” because they construct their social order in accordance with nature’s clock. The fish, alternatively, are detestable characters because they continue to persevere through the nighttime hours. The author’s description possesses two subtextual messages. The first is self-depricating, as the fish seem aligned with the realities of Victorian factory life. They are going through a “performance,” and it is “painful [to watch] the bright-eyed wakefulness of those fish” (447). The phrase “bright-eyed” is often used to describe children, and since it is “painful” to watch them be awake so long, the description can be assumed as a parallel description of the condition of the child worker. The second is relating to colonized peoples, as the author seems to be stating that the issues of exploitation are prevalent world-wide, and that there are both moral and amoral people in any given region. In both messages, morality is once again tied to social order and industry.

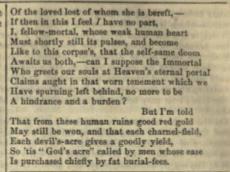

Bleeding Good Red Gold in “Misnamed In Vain”:

Misnamed in Vain 2

Description of the moral justifications given by the upper-class for worker exploitations

This final source is the most explicit on this page. It directly discusses morality in relation to industry, solidifying the relevance of Goodland’s reading and establishing it as an apt reflection of contemporary Victorian sentiments. The speaker states that “sickness, death, / Vice, poverty, [and] corruption” run rampant on London’s streets (444). They do not assign blame to a human subject, however, instead stating that “London’s dead, / not by night only, but by broadest day, send murderous ghosts, whose mission is to slay / Her living” (444). As well, London’s dead does not affect a human subject, but instead affects the “tumbling stones / That seemed themselves too sick to stand erect” (444).

The author of this poem seems to be arguing that the London’s innate spirit has succumbed to corruption. There is a preternatural disturbance that will continue to cause harm if left unchecked. Sickness, death, vice, poverty, and corruption are all trademark traits of urban Britain in the wake of industrialization. By not assigning blame to a human subject, the speaker appears to acknowledge these qualities have become so deep-rooted in the country that they are systemic. Condemning the action of a single individual or group of individuals, therefore, would be futile. This reflects Goodland’s conception of morality, as well. By turning the issue of corruption into an issue of a country’s spirit, the speaker is suggesting that its failing industrial framework is not a matter of economy but instead a matter of spirit. Death is so common to the speaker, as they walk on “festering bones” (444). This appears to be the reason why they do not cite London’s human citizenry as in danger in the first three stanzas. That ship has metaphorically sailed, as human casualty is so rampant. No, now the danger lies in the stones that make up London’s walls—the nation’s very foundation is at risk of deteriorating.

The final two stanzas refocus the poem onto a human subject. The fact that the author chooses to begin their poem by exploring the city’s spirit only to move later to the human subject proves that, in Victorian morality, social order is the conduit through which they conceptualize human virtue. The speaker states that

I, fellow mortal, whose weak human heart

must shortly still its pulses, and become

Like to this corpse’s

… no more to be

A hindrance or a burden

But I’m told

That from these human ruins good red gold

May still be won

They make an appeal to the human subject through the familiarizing word “fellow.” The reader is, therefore, more likely to equate their self-conception with that of the speaker’s. So, when the speaker states that they are merely a hindrance to London when alive, it evokes a sardonic, cynical tone that critiques the anti-humanism of the industrial present. The final stanza references a human fault, one that is separate from London’s spirit. The line “but I’m told” is situated on the far-right of the stanza, almost concealing it. This suggests that the following statement is a rhetoric some people strive to poverty proliferate. The sentiment is that industrialization is necessary for profit, and, by extension, so is death. For the speaker, the yields of the industrial world are covered in red.

Conclusion

Juxtaposing our reading of Great Expectations’ final chapters with the extratextual publications in All the Year Round affects both how we, as modern readers, interact with the novel and enlightens us to how contemporary readers were similarly affected. The above materials appear unrelated. I mean, you could venture an argument that zoology and ancient quack’s both evoke a certain waterfowl, and I would applaud your pun, but outside that there is no real apparent through line. Upon closer reading, though, we can begin to notice the consistent appeals to human character and questions of what constitutes a moral spirit. Lauren Goodland’s article provides illuminating context of Victorian-era morality that helps us make sense of these through-lines. Essentially, her reading helps us understand that there is a subtextual rhetoric throughout this edition of All Around The World. This rhetoric argues that good morality is connected to good economic practices, which is reflective of the synthesis between industry and society in the Victorian-era. Readers would likely latch onto and replicate the cohesive sentiments in this edition, and so, by understanding it better, we can better understand those readers. As well, we can better understand the novel itself. By constructing Great Expectations as a bildungsroman, we understand that it depicts a moral journey for Pip. Yet, Pip’s moral journey is highly reflective of the questions being raised by these other authors about London’s morality. Perhaps, then, we can regard Great Expectations not only as a bildungsroman for Pip, but as one for Britain itself too.

Works Cited

“A Night in the Jungle.” All The Year Round, edited by Charles Dickens, Chapman & Hall, No.119, 03 April 1861, pp. 444-449.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. Edited by Graham Law and Adrian J. Pinnington, Broadview Press, 1998.

“Drift: Ancient Quacks.” All The Year Round, edited by Charles Dickens, Chapman & Hall, No.119, 03 April 1861, pp. 443-444.

Goodlad, Lauren. “Moral Character.” Historicism and the Human Sciences in Victorian Britain, Cambridge University Press, 2017, pp. 128-153. https://www-cambridge-org.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/core/books/historicism-and-the-human-sciences-in-victorian-britain/moral-character/D6936406FE76D077ACB04F60A8BFBA53. Accessed 06 April 2023.

“Misnamed in Vain.” All The Year Round, edited by Charles Dickens, Chapman & Hall, No.119, 1861, pp. 444.

Schweizer, Florian. “The Bildungsroman.” Charles Dickens in Context, Edited by Sally Ledger and Holly Furneux, Cambridge University Press, August 2012, pp. 140-147.