Great Expectations and America's North and South

Mona Kadri

The Victorian era was a period with many stark and unique attributes, and arguably one of the most notable was the literature that it produced. The period had countless great writers, many of which we still study today. A very well-known author of the time was Charles Dickens. He has written a great deal of books, however, one that noticeably stands out is his Great Expectations. There has been much discourse on the novel. The story sparks extensive conversations about child labor, the justice system, slavery, and many more complex topics. Many scholars and academics have contributed to the discussion and have provided different angles and understandings. One of these academics and their contribution is John O. Wallers, and his paper “Charles Dickens and the American Civil War.” In this paper, Wallers argues that prior to December of 1861, months after the Civil War had started in April of 1861, Dickens was pro-Northern and anti-Southern, but that he later switched sides and becomes anti-Northern and pro-Southern. Wallers writes: “We shall see that for the first year after secession [of the war] Dickens’ policy was pro-Northern but thereafter was pro-Southern.” (Wallers 535). Wallers titles his paper “Charles Dickens and the American Civil War,” yet he only quotes, references, and bases his conclusion on All the Year Round, a European magazine. Wallers fails to also consider the novel in its American context: a magazine titled Harper’s Weekly. One cannot talk about Charles Dickens and America without looking at the American context, as this changes our understanding of the characters and plot within Great Expectations and provides different insights. When looking at Harper’s Weekly and the content within it, we can see that Dickens’ characters and plot reflect his beliefs and criticisms about America’s North and South, rather than just the North or South within the first year of the war. This can be seen through Dickens’ depiction of fugitives and the justice system, as well as his portrayal of Pip as both a child doing labor and as a commodity.

Much like many of his novels, Dickens largely includes the theme of fugitivity in Great Expectations. In June of 1842, Charles Dickens traveled to America, and wrote about his experiences in a travelogue he titled American Notes for General Circulation. One of the chapters within this travelogue is “New York.” In this chapter, he writes about his experience when visiting a New York prison, and how the inmates are treated poorly. When Dicken’s asked when they receive exercise, the prison officer responds that “they do without it pretty much.” (Dickens 57). Furthermore, when Dickens notes that the prisoner’s clothes are on the floor, the officer asks, “where else should they put them?” (Dickens 58). Thus, due to these experiences, it comes as no surprise that Dickens continues to include fugitivity in his novels. This theme is especially prevalent in Great Expectations, as one of the first characters we are introduced to is Magwitch, a runaway convict. He later becomes a central character in the novel as he is the person who gives Pip his expectations. However, even when we are not looking specifically at Magwitch, criminality and justice/ the justice system, are an evident and reoccurring theme. Chapter XVIII (18) of the novel opens with a scene of Mr. Wopsle, Joe, Pip, and a few other acquaintances sitting together as they discuss the news. A murder has been committed, and the group of men agree that the suspect is guilty. However, Mr. Jaggers, a lawyer from London, approaches them and questions their confidence. When they inform him that they believe the suspect to be guilty, he reprimands them and asks: “Do you know, or do you not know, that the law of England supposes every man to be innocent, until he is proved – proved – to be guilty?” (Dickens 166). This scene can be further understood when looking at the context it was published in. In February 9th of 1861, Harper’s Weekly published a story titled “The Case of Anderson.” The article centers around a runaway Slave named Anderson who escapes the “tender mercies of the sanguinary Missouri slave trade.” (Harper’s 87). Anderson’s escape is secured due to European involvement. When looking at “The Case of Anderson” alongside chapter 18 of Great Expectations, we can see that the article gives a different understanding of the chapter. The article demonstrates the ill treatment of fugitives, including those from the slave trade, and the unjust acts committed within the American justice system. Similar to Anderson, the convict in which Wopsle and his colleagues are discussing are ill-treated and seen in a negative light. Furthermore, that fact Anderson is freed due to England’s law, and the fact that Jaggers interrupts and defends the fugitive by stating that a man is innocent until proven guilty under the law in England, reflects Dickens’ belief that the practices within America’s South and North are inadequate and unfair. Even more so, later on in the novel, Magwitch is proved to be a caring and virtuous character, who, despite being named a convict, was not entirely guilty of the crimes he “committed.” These characters and plots demonstrate the critiques Dickens’ is making towards America’s North and South and their justice system.

Another aspect that Charles Dickens heavily focused on was child labor. In the 18th century, Britain underwent a great change in the form of the Industrial Revolution. The Industrial Revolution brought with it many horrid things, one of which was child labor. Children as young as six years of age were forced to work in harsh and demanding conditions. However, Britain was not the only country to instate child labor. Due to the free labor movement in America’s North, an upper and lower-class began to emerge. Due to this, those of the lower class began forcing their children to work in order to gain a suitable living.

This can be seen in the February 9th installment of Harper’s Weekly in 1861. When looking in the advertisement section of the magazine, there is an advertisement for Jewlery Agents. The advertisement calls for “Men, Women, and Boys.” (Harper’s 95). The notice is looking for people, as well as young boys, to come and work as jewelry agents, and to sell the jewelry for the company. Naturally, this is a call to the lower class as it calls for children to work, thus making them do labor. A similar narrative of child labor can be found in Great Expectations. Pip is born to a lower-class family and lives with his sister and brother-in-law, Joe, who owns a forge. Furthermore, when Pip is just old enough to start working, he becomes an apprentice to Joe. Chapter 18 of the novel opens with the line: “It was in the fourth year of my apprenticeship to Joe...” (Dickens 165). Pip is about the age of thirteen at this point in the novel, and so he has been working in the forge with Joe since the age of eight or nine. Furthermore, Pip is forced to do this despite his dislike for the work because he is of the lower-class and must earn a living. Naturally, the work that Pip is doing is depicted in a negative light within the novel, thus pushing the idea that children of that young age should not have to work. In contrast, when he visits the Pockets in London, none of the younger children within the house are working to earn a living or help with the expenses, as they are part of the upper class. When examining Pip’s situation, the advertisement allows for a different perspective and for certain aspects of America to be drawn out. It allows us to better understand why Dicken’s wrote Pip’s situation into the novel. The circumstances in which Pip finds himself are reflective of the child labor happening in America’s North due to free labor and the class divisions it is causing. Dicken’s uses Pip’s character, and casts a negative light onto it, as a means of critiquing the conditions that the North in America are forcing upon the children of the lower-class.

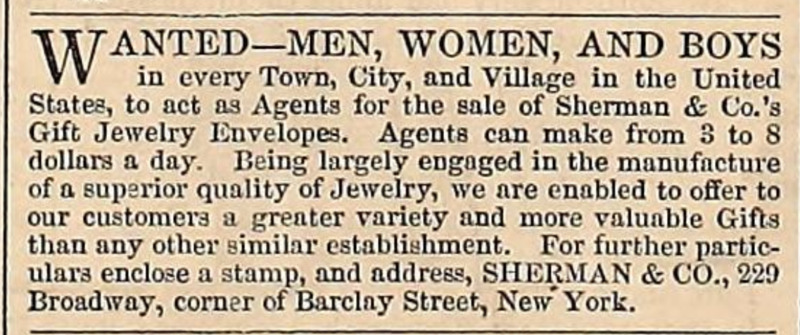

As previously mentioned, Dickens’ wrote a book based on his experiences in America titled American Notes for General Circulation. In this book, he dedicates a section to slavery. Within the first lines of this chapter, he mentions that the system has “atrocities.” (Dickens 159). Immediately, Dickens establishes that he is anti-slavery and that he does not approve of the system within the South. Dicken’s resentment for the system is evident in Great Expectations. In chapter 18 of the novel, Mr. Jaggers asks to speak with Pip and Joe privately. He then informs the both of them that Pip has received great expectations from an anonymous doner. Pip and Joe agree to take this opportunity. When Pip agrees to go to London, Jaggers asks Joe how much he wishes to be compensated for Pip. Joe does not understand and asks: “As compensation for what?” To this, Jaggers replies “For the loss of his services.” Joe is outraged at Jaggers’ reply, and states “...if you think as – Money – can make compensation to me – for the loss of the little child – what come to the forge – and ever the best of friends!” (Dickens 173). In this scene, we can see that Pip is seen by Jaggers as an asset or a commodity rather than a person, like Joe sees him. Jaggers expects that money will be able to compensate for Pip, and that his only value lies in what he can contribute to the forge. A similar theme can be found when looking at both a comic strip and a quick article in February 9th, 1861’s installment of Harper’s Weekly. The comic depicts both the North and the South in conflict with one another. One is selling corn and the other cotton. By the end of the comic, they compromise and trade with one another, as a solution. However, what sticks out in this comic is not the North nor the South, but rather, the fact that throughout the comic, there is a Black man, presumably a slave, standing in the back. He continues to do so throughout the entire comic, and does not speak, nor is he spoken to. Therefore, although he is present and relevant, he is not consulted about the decision, even when it heavily concerns him.

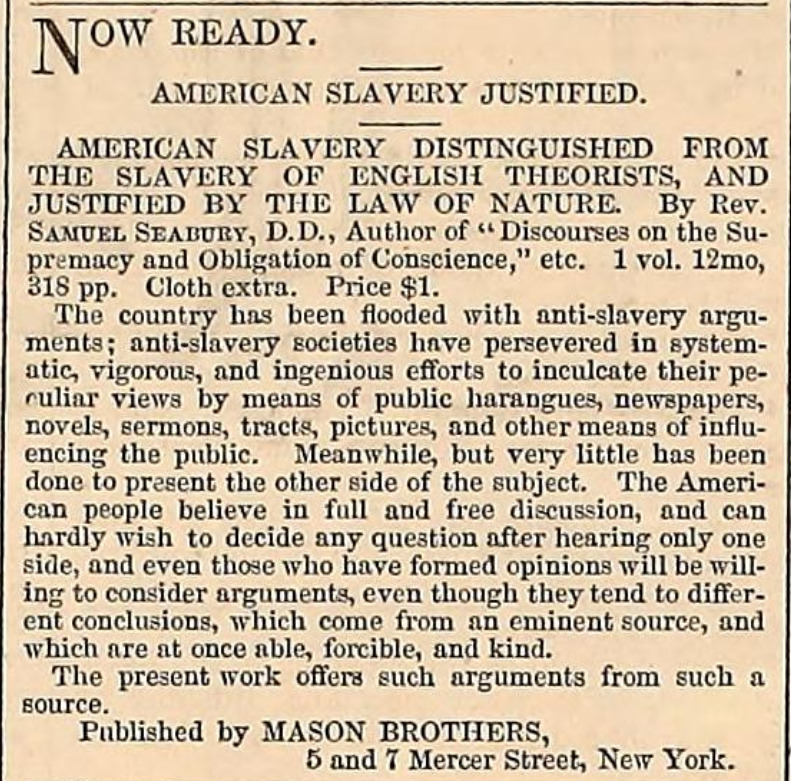

The article mentioned also pertains to slavery. The article is titled “American Slavery Justified,” and goes on to say that slavery is “justified by nature.” (Harper’s 95). We can see from this that the South is attempting to justify slavery by stating that it is in the nature of Black people to be commodities rather than people. We can see a clear parallel between the article, the comic, and the way in which Pip is regarded by Jaggers. In all three cases, these men (Pip and the two slaves) are not seen as people, but are instead seen as something material. Their value does not come from their person, but rather the services that they can provide. Furthermore, the fact that Dicken’s writes Joe’s speech about how Jaggers cannot “compensate” for the loss of Pip demonstrates Dickens’ views on slavery. When looking at Great Expectations and Harper’s Weekly, at the same time, we can understand that Dickens’s is criticizing slavery and the treatment of slaves in America’s South.

When looking at and interpreting a work, it is important to look at the context in which it was published in. This allows us to gain a better understanding of the text. Although John O. Wallers consults All the Year Round it is also important to examine Harper’s Weekly, especially when looking at Charles Dickens and America. Through looking at Harper’s Weekly, we can see that Dickens critiques both the North and the South of America through the plot and characters within his novel Great Expectations. This furthers the conversation about who Charles Dickens was and where his beliefs lie.

Works Cited

Harper's Weekly, "The Case of Anderson." Harper's Weekly, 9th February, 1861, pp 95.

Harper's Weekly, "The North and the South." Harper's Weekly, 9th February, 1861, pp. 96.

Mason Brothers. "American Slavery Justification." Harper's Weekly, 9th February, 1861, pp. 95.

Harper's Weekly, "Wanted - Men, Women, Boys!" Harper's Weekly, 9th, February, 1861, pp. 95.

Dickens, Charles, "Greeat Expectations," Broadview, 1861.

Dickens, Charles, "American Notes for General Circulation," 1842.

Waller, John O., "Charles Dickens and the American Civil War." Studies in Philology, vol. 57, no.3. 1960, pp. 535-548.