Part 28

Between April 12th, 1861, and April 9th, 1865, the United States of America was undergoing a civil war between the Northern Union states and the Southern Confederate states. At this time publishers of weekly and monthly magazines, like Harper and Brothers who published both Harper’s Monthly and Harper’s Weekly magazines, not only needed to provide important, informative updates on the war itself, but were also tasked with keeping up the morale of both civilians and soldiers alike. To do so, they, as well as other publishers, created contracts with British authors like Charles Dickens for the rights to publish advanced chapters of their work, which gave them an important advantage in securing readers as they could be the first to publish the next serialized installment. Upon resolving international copyright issues, Charles Dickens and his published works were able to become a unifier among American readers and a house-hold name that contributed to the morale of both American soldiers and civilians during the civil war in between 1861 and 1865.

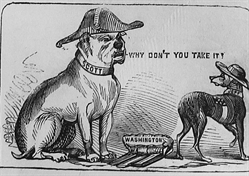

The early days of the American publishing industry was built upon the infringement of intellectual works by mainly British authors like Charles Dickens due to a lack of international copyright law. According to those against implementing a standard for importing foreign works, the “appropriation of foreign texts was indeed an act of democracy and public education” for American readers, and, as for the publishers, it was thought to be “a way of protecting American business interests and a means of illuminating the public” (McParland 39). Since reprinting previously published chapters could be done “at one-fortieth the cost of the British two-volume version” (McParland 39), it ignited the competitive culture of American publishers in the late 19th century. Dickens’ name was already well-known and wide-spread by the 1840’s, his works being “widely read and commercially desirable property that reached American readers through both his British publishers and through less official American publishers’ efforts to gain access to his works” (McParland 38) following the unauthorized reprinting of the Paperwick Papers in 1837.

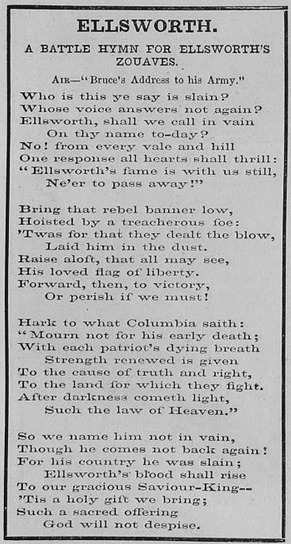

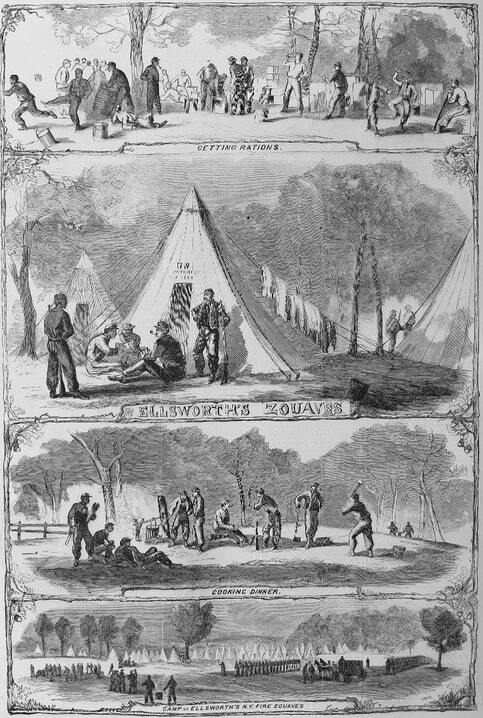

By the 1840’s, “Charles Dickens was soon at the center of a piracy struggle among competing American publishers” and due to the growing “dependency upon British texts by American publishers for income and by audiences for reading material” (McParland 44), eventually publishers were persuaded to replace unofficial re-prints with official contracts with the British authors. Charles Dickens’ work “intersected with public and private life [and] participated in America’s struggle for nationhood and self understanding” (McParland 45). It would soon be clear that Charles Dickens “was a particularly popular and resonant force among the American public” (McParland 45). According to McParland, “Dickens’s emphasis on the transatlantic distribution of his new journal All the Year Round suggests his growing awareness of his American audience [and] is also underscored by the deal he made with the Harpers, who paid him 1250 pounds for advanced sheets of Great Expectations” (113). With Dickens’s work already being a popular and sought-after passtime for many American readers, it may come as no surprise that his novels “served as one link between family members or friends whom the war set at a distance from each other” (McParland 113). As America became split and a war began to rage between the Northern and the Southern states, “[t]he exchange of letters, newspapers, and fiction among soldiers and their families helped them to maintain affective ties” (McParland 113). It was important to keep the minds of soldiers busy and active in order to help maintain the strength and comradery in the armies, and to stave off depression, fatigue, or listlessness. Novels and humor, both published in serialized magazines, “were a substitute for action, a guard against idleness and boredom” (McParland 114) as well as a means to lift spirits and encourage a sense of community, and “serialized fiction brought sentiment and contact with friends and family closer for readers in an America ravaged by war” (McParland 123).

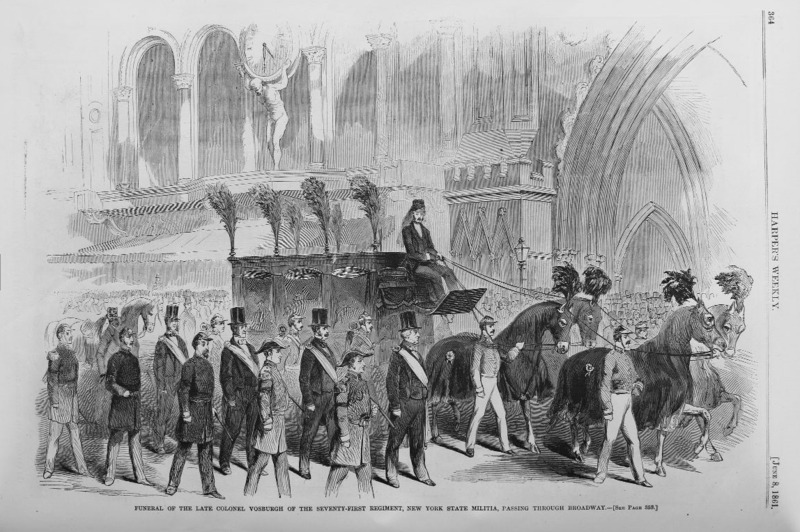

As Great Expectations was published in Harper’s Weekly, it “circulated among communities of readers [...] including civilian readers, public officials, and soldiers in camp or in hospitals or prisons” (McParland 123), and even served as an example for many; Pip’s experiences of being “tossed into new discoveries, given new roles, and [shown] the value of their relationships” (McParland 124) encouraged Americans on both sides of the war to do the same, and “helped them endure periods of hardship or waiting” (McParland 124). As the same papers that published Dickens’s chapters were the same that often included important updates on the ongoing war, his stories “were read in connection with American issues” (McParland 124) and made significant contributions “into the cause of maintaining hope” (McParland 124) when much of the papers were dominated by the tragic and frightening realities of war and cultural concerns, including death and losses of important figures of the time.

Similarly to the characters in novels like Great Expectations, Dickens’s audience “dwelled in time-conscious worlds” (McParland 34). Miss Havisham, for example, “attempted to stop the flow of time” by reclusing herself in a single moment of her life, likely a common wish among those living in a time of war, but “the serial form of the story itself insists upon time’s unceasing flow” (McParland 34). Audiences may have been able to see themselves in these characters as they were “experiencing similar liminality” (McParland 35) and the serialized nature of Dickens’s novels “was itself suggestive of the age’s sense of motion and progress, expansion and transition” (McParland 35) that embodied life during national insecurity in the 1800s. As a consequence for Dickens’s widespread popularity in America across the 1800s, many finished, compiled copies of his novels were bound and sold or kept in libraries for public use. While he “was not always the most frequently borrowed author [...] he was one who had [a] wide and lasting impact across all classes, ages, gender, and across several decades” (McParland 71). The YMCA library in Milwaukee, for example, “shelved 15,000 volumes” (McParland 71) of Harper’s Weekly at one time, and also stocked Dickens’s All the Year Round and Household Words. His novels also became popular in circulating libraries, aimed to provide access to published works in more rural areas.

Charles Dickens’s cultural impact on the United states of America by no means started at the beginning of the Civil War, but as the importance of staying informed rose, as well as the need for American citizens to find ways to occupy their minds, Dickens’s popularity across the country grew and cemented his place among popular American culture. Printed alongside updates on the state of the war were chapters of his novels, serialized in publications like Harper’s Weekly and Harper’s Monthly and distributed to those on either side of the war. His stories served as examples of hope and the importance of family, as well as mental and emotional stimulation for those left idle at their posts or in their homes. Communal readings of novels like Great Expectations were imperative for keeping up morale and a sense of comradery among soldiers, or for feeling connected to those they had been forced to leave far away, and, thanks to the contracts with publishers like the Harper Brothers, Dickens was able to secure himself a permanent place in both American history and culture.

Works Cited

Harper’s Weekly, Volume 5, Issue 232, 8th June 1861, pp. 353-64

Law, Graham, and Charles Dickens. Great Expectations. Edited by Graham Law and Adrian J. Pinnington, Broadview Press, 1998.

McParland, Robert. Charles Dickens's American Audience, Lexington Books/Fortress Academic, 2010. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/lib/ucalgary-ebooks/detail.action?docID=616238.