Part 28 - Erica Lonnberg

Wilkie Collins’ novel The Moonstone is published within different historical frameworks: American newspaper Harper’s Weekly and Charles Dickens’ English magazine All the Year Round. In Harper’s Weekly, installments of The Moonstone are infused with American illustrations, advertisements, and cartoons responding to American events and ideals post-civil war. Contrastingly, in All the Year Round, chapters of The Moonstone are book-ended by literature such as poems and short stories, excluding illustrations and advertisements. Nevertheless, both texts alter the reader’s perception of significant themes and events in The Moonstone by including text and visuals of American and English attitudes in the nineteenth century. Mary Elizabeth Leighton and Lisa Surridge’s article “The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper’s Weekly” suggests “that Victorian serial illustrations do not merely reflect or supplement the verbal text but constitute plot elements per se, thus profoundly affecting the narrative's unfolding and meanings” (210). Therefore, it is essential to examine the illustrations and advertisements in Harper’s Weekly in contrast to the standalone chapter of The Moonstone in All the Year Round to understand the historical context in which the novel is framed within two separate publications.

This exhibit will examine how the fear of the foreign Other and racial mixing, prolific topics in post-war America and Victorian England, are presented differently in Harper’s Weekly and All the Year Round. Ezra Jennings, a mixed-race character, is “potentially the most controversial” character due to his liminal identity that transcends binaries of racialized space (Leighton and Surridge 233). In Harper’s Weekly, Ezra’s conflicting appearance complicates American perceptions of the Other; simultaneously invoking feelings of sympathy and ostracizing him as a foreign counterpart “against the domestic” due to his exotic appearance and non-traditional medical practices (Leighton and Surridge 213). However, in All the Year Round, Ezra’s racial identity is left to the text’s description, heavily fixating on his unusual features in contrast to the English domestic hero, Franklin Blake. Congruent with the literature that follows the chapter, Ezra’s character embodies Victorian anxieties of the Other that threaten English standards.

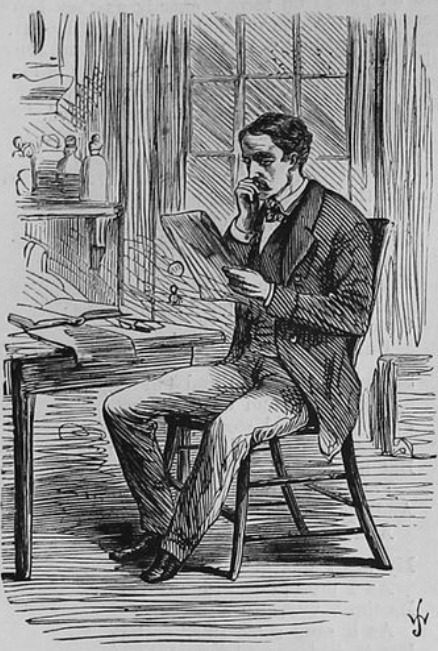

William Jewett’s illustration in Harper’s Weekly captioned “Chapter X,” portrays Franklin Blake seated in Ezra Jennings’ surgical room reviewing “manuscript notes” (Collins 371). Franklin is displayed as a refined gentleman with proper posture and an appearance of thoughtful contemplation. Despite Franklin’s description of “the furniture of the room,” including “A book-case filled with dingy medical works, and ornamented at the top with a skull,” Franklin’s background does not reflect these strange surroundings, separating him from foreign space (Collins 370). Franklin, in contrast to the lightness and plainness of his background, is the main focus of the illustration, analogous to his role in the novel. Taking on the lead detective role, Franklin is the model English hero who must establish his innocence.

Leighton and Surridge note “The pattern of multiple images on the first page of each serial part of the American Moonstone created complicated interpictorial effects through tensions, parallels, and ironies of their placement” (211). Despite this scene chronologically taking place following Jewett’s second illustration of the chapter, “I found Ezra Jennings ready and waiting for me,” the illustration of Franklin appears first on the page. Franklin is the first and primary focus of the reader before reading the chapter, foreshadowing his role as an idealized English hero in contrast to the perceived Other, Ezra Jennings.

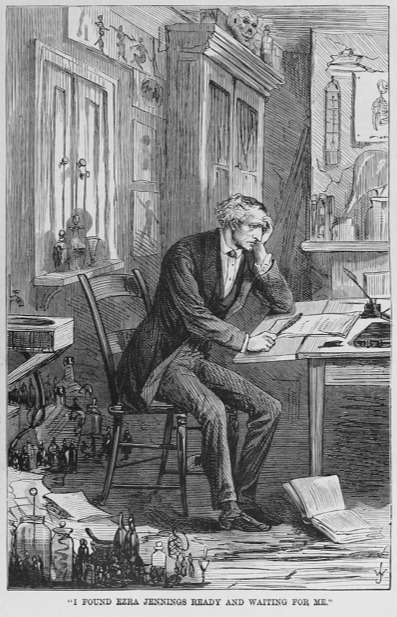

Ezra Jennings’ “mixed race … posed an ideological problem for Harper’s” due to a heightened focus on “miscegenation and racial identity” following the Civil War (Leighton and Surridge 234). William Jewett’s illustration presents Ezra as a dark figure appears to blend in with the darkness of his background and the exotic surroundings of dancing tribal drawings and a skull ornament. Juxtaposed with Franklin’s polished setting, Ezra’s atmosphere of bizarre items and disorganized books distances him from refined domestic space and forces him into unknown, foreign territory. Ezra’s appearance is not only unfamiliar to the domestic eye, but his medical practices of questioning and experimentation are progressive and unconventional. The disorder of his medical supplies symbolizes Ezra’s urgency in proving Franklin’s innocence. He persistently interrogates Franklin about his state of mind during the night of the moonstone robbery, taking on the role of a secondary detective, “guiding Franklin into his own dreams and sleep to find the mystery’s solution” (Leighton and Surridge 233). Hunched over a table with a pen in hand, Ezra has the power to write the narrative of the hero’s innocence despite contrasting the English detective image of Franklin.

Although Ezra’s exotic side is reflected by his multi-coloured hair, hooked nose, and exotic backdrop, Ezra’s skin appears White in this particular illustration, complicating the reader’s understanding of his identity. Leighton and Surridge suggest Ezra occupies a “liminal” space as he embodies both British and foreign elements (231). Ezra’s duality is visually represented by the stark contrast of his half-black and half-white hair, his White skin but an exotic backdrop. As a result of these multifaceted representations, Ezra elicits a dual response from Collins’ audience; he is a threat to domestic space due to his unconventional appearance but also a secondary detective who commits his life and suffering to proving the innocence of the protagonist, Franklin.

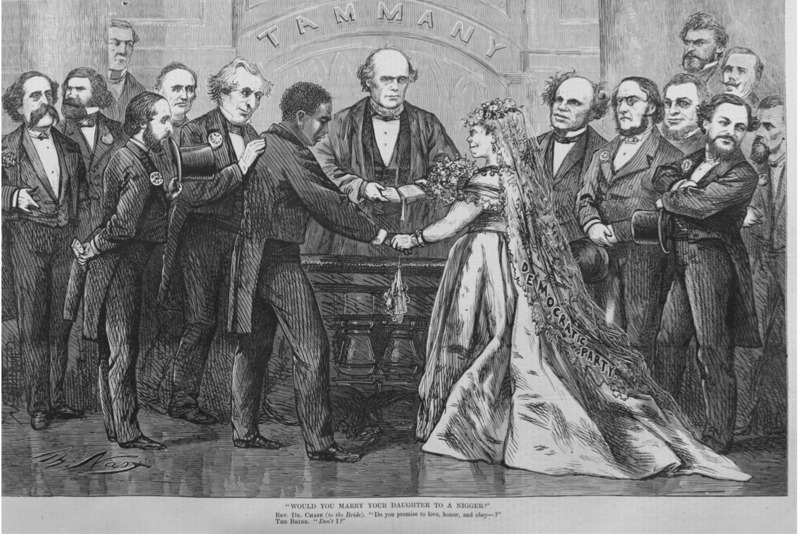

Thomas Nast’s cartoon serves as a critical lens of the political climate surrounding the publication of The Moonstone in Harper’s Weekly. The cartoon depicts a Black man marrying the Democratic Party, represented by a White woman. Noted in the caption, Salmon P. Chase is the officiator at the wedding as “he sought to broaden the [Democratic] Party’s appeal and move it toward coalition with antislavery elements” (Blue 211). Nast emphasizes the irony of Chase’s Democratic presidential nomination as the Democratic Party opposed Chase’s “advanced racial views” in nineteenth-century America (Blue 232). Moreover, the marriage metaphor implies a union fraught with contradictions and deceit given “the racial tensions of that period” (Blue 232). When Chases asks the Bride, a symbol for the Democratic Party, “Do you promise to love, honor and obey—?” she responds, “Don’t I?” with a perfidious smirk, suggesting that the political organization will fail to respect Chase’s antislavery ideology when put into power.

The cartoon reflects nineteenth-century fears of miscegenation following the Civil War. As both figures come into close contact with domestic spaces the fear of the Other and concern for national stability in post-war America is amplified. Ezra’s appearance is described as “the mixture of some foreign race in his English blood,” by Franklin, suggesting Ezra’s foreignness contaminates his Englishness from the perspective of the model English man (Collins 356). Comparably, the Black man in the cartoon is perceived to disrupt the Whiteness of his bride and the Democratic institution as reflected by the question, “Would you marry your daughter to a [Black]?” These themes “frame the particular tensions surrounding the character of Ezra Jennings” as he intrudes on English space as a half-White, half-detective (Leighton and Surridge 234).

In contrast to the American version of The Moonstone, All the Year Round does not include illustrations of characters in the story, meaning the historical context of the publication can be observed through the literature following the chapter. The anonymous digest, “Animal Intelligence,” reflects Victorian anxieties of human devolution, specifically through the lens of animals as “our inferior brethren” (113). However, this fear of regression can be applied to Ezra Jennings as, due to his mixed-race identity, he is also viewed as inferior in comparison to his English counterparts, enduring the harsh treatment of a mere animal.

While Ezra describes the opium experiment to Franklin, he must attest to his intelligence ny framing his ideas through the lens of Englishness due to his exotic roots and progressive empirical practices. When Ezra ensures Franklin of his opium expertise due to his ability to explain this procedure “under the influence of a dose of laudanum,” he supplies Franklin with the book “Confessions of an English Opium Eater” to support his claims (Collins 379). By supplying Franklin with a book of English roots, he provides Franklin with “testimony, which will carry its due weight … in [Franklin’s] mind, and in the minds of [Franklin’s] friends” (Collins 379).

In “Animal Intelligence,” a man performs an experiment on a bug to observe if it can detect the presence of a human as a way of reflecting the bug’s intelligence. In the experiment, the bug “dropped plump on the observer’s nose,” emphasizing the bug’s ability to detect a human (“Animal Intelligence” 114). Despite the clear implications of the bug’s actions, the author questions the creature’s intelligence due to its inferior status, asking “Was this, or was this not, an act of intelligence?” (“Animal Intelligence” 114). For both Ezra and the bug, their intelligence must be testified through the perspective of the dominant narrative due to their status as less than human; the human in “Animal Intelligence” and the English gentleman, Franklin, in The Moonstone. At the end of the chapter, Franklin states, “In the pages of Ezra Jennings, nothing is concealed, and nothing is forgotten. Let Ezra Jennings tell how the venture with opium was tried,” vouching for Ezra’s honesty and intelligence to the skeptical reader (p. 383).

While Leighton and Surridge contend that illustrations of non-White characters elicit sympathy from the reader, I posit that, like Ezra’s conflicting identity, the perception of mixed-race characters is complex and multifaceted in The Moonstone. In Harper’s Weekly Ezra appears as a detective counterpart to Franklin Blake; he interrogates Franklin to ultimately solve the mystery of the moonstone. As a tormented scientist, Ezra is hunched over his work, dedicating his life to exonerating Franklin from prosecution. However, when compared to the illustration of Franklin as a proper gentleman situated as the focus of the image that precedes the illustration of Ezra, it is significant that Ezra is subjected to dark, foreign space to underscore his identity as the perceived Other. Ezra embodies miscegenation, heightening anxieties about foreign bodies intruding on domestic spaces. Similarly, in All the Year Round, the reader’s perception of Ezra is dependent on the description of his unusual appearance as half-foreign, half-English. With a fixation on his racial identity and mixed appearance, Ezra is dehumanized and reduced to a mere symbol of Otherness and regression of refined English space.

Works Cited

Blue, Frederick J. “The Moral Journey of a Political Abolitionist: Salmon P. Chase and His Critics.” Civil War History, vol. 57, no. 3, 2011, pp. 210–33, https://doi.org/10.1353/cwh.2011.0035.

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone. Oxford University Press, 2019. Print.

Jewett, William. "Chapter X." Harper's Weekly, 11 July 1868, p. 437, https://go-gale-com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/ps/navigateToIssue?volume=12&loadFormat=page&issueNumber=602&userGroupName=ucalgary&inPS=true&mCode=96EY&prodId=AAHP&issueDate=118680711&aty=ip

---. “I found Ezra Jennings ready and waiting for me.” Harper’s Weekly, 11 July 1868, p. 437, https://go-gale-com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/ps/navigateToIssue?volume=12&loadFormat=page&issueNumber=602&userGroupName=ucalgary&inPS=true&mCode=96EY&prodId=AAHP&issueDate=118680711

Leighton, Mary Elizabeth, and Lisa Surridge. “The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper’s Weekly.” Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 42, no. 3, 2009, pp. 207–43, https://doi.org/10.1353/vpr.0.0083.

Nast, Thomas. “Would You Marry Your Daughter to a [Black]? (Original Title: Would You Marry Your Daughter to a Nigger?” Harper's Weekly, July 11, 1868, p. 444, https://go-gale-com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/ps/navigateToIssue?volume=12&loadFormat=page&issueNumber=602&userGroupName=ucalgary&inPS=true&mCode=96EY&prodId=AAHP&issueDate=118680711&aty=ip

Unknown Author. “Animal Intelligence.” All the Year Round. 11 July 1868, p. 113, Dickens Journals Online, https://www.djo.org.uk/all-the-year-round/volume-xx/page-113.html