Part 27 - Maia Pearson

Introduction

How can readings of a Victorian novel be influenced by its publishing context? In the 27th installment of Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone, the introduction of the character of Ezra Jennings is influenced by the various illustrations, literary works, and advertisements that surround Collins’s text. This project will extend a debate brought forth by John Glendening’s article, “War of the Roses: Hybridity in ‘The Moonstone,’” and Mark Mossman’s “Representations of the Abnormal Body in ‘The Moonstone’” by connecting Glendening’s argument that Ezra’s race in The Moonstone presents a “violation of the [Victorian] natural order” (296) to the harsh racial connotations of Harper’s Weekly’s periodicals illustrations and advertisements, and link Mossman’s statements that “Wilkie Collins’ engagement with the abnormal body is often defined by a larger kind of anxiety” (486) to the depictions of illness in All the Year Round. The first two items offer differing depictions of Ezra’s physical body in The Moonstone as the “Have You Ever Been Accustomed to the Use of Opium” illustration presents his character as strange and otherworldly while the poem, “Blossom and Blight,” draws pity to his ill-stature by drawing a comparison between his frailty and the effect of old age on the body. Meanwhile, the advertisements of the two publications also influence readings of The Moonstone as they provide an avenue to combine the analysis of Jennings’s race and disability by claiming to provide cures for skin discolouration that can purify the blood. This project will argue that while the two periodicals depict Ezra’s body in a similar way, they cannot be viewed as the exact same text because All the Year Round feeds into Victorian anxieties about how Ezra’s condition could be a part of any person’s life, while Harper’s Weekly targets the racial elements of identity that make Ezra appear as a problem that needs to be solved.

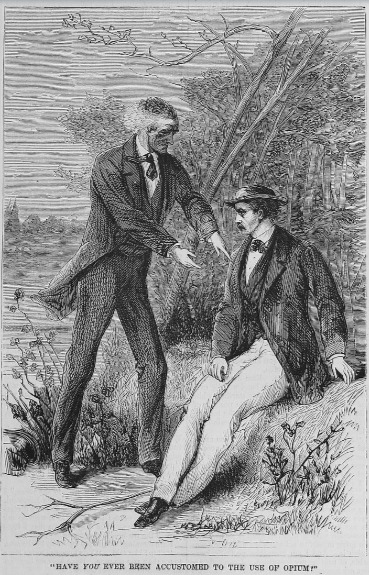

Harper’s Weekly’s “Have You Ever Been Accustomed to the Use of Opium” illustration contributes to the American depiction of Ezra Jennings as someone to be pitied for his race by depicting his physical body as strange when compared to the gentlemanly image of Franklin Blake. In this image, Jennings’s “extraordinary parti-coloured hair,” “fleshless cheeks,” and “gaunt facial bones” (Collins 356), are his most recognizable physical traits, with his thin and disheveled figure looming over Franklin. This direct contrast between the chaotic nature of Ezra’s appearance and the put-together look of Franklin plays into Glendening’s point that the strangeness of his character is meant to convey to Victorian readers a sense of moral ambiguity because of his mixed-race and chaotic depiction (492-3), making Franklin seem stable because he does not hold any of these specific characteristics. Additionally, this image emphasizes a point made by Franklin in the text when he regards Ezra as, “[Having] suffered as few men suffer; and there [is] the mixture of some foreign race in his English blood,” (Collins 359), by featuring his “gaunt facial bones” and darker skin. Because his figure is so diminished while carrying these traits, this context makes Ezra’s mixed-race heritage seem wrong because it threatens the “[Victorian] natural order” (Glendening 296) that favours paler complexions and able-bodied men. This racist and biased view of Harper’s Weekly towards Ezra’s body creates an idea that he is to be pitied for his differences, rather than due to the unfortunate things that happened during his life that led him to his position as a slandered medical assistant.

Compared to the Harper’s Weekly periodical, All the Year Round makes Ezra Jennings seem like a character to be sympathized with because of how Victorian society has treated him, rather than ostracizing him for his race. It accomplishes this sentiment with the placement of “Blossom and Blight,” a poem by an unknown author, five pages after the 27th installment of The Moonstone. “Blossom and Blight” showcases aged workhouse employees reminiscing about their childhoods out in the countryside before they die as a result of their frailty from harsh workhouse conditions. The lines, “[T]he old man is drooping; they’re ringing his / knell, / And the scenes of his boyhood fade out of his sight,” relate to Collins’s text with descriptions of Ezra “suffer[ing] from an incurable internal complaint … [he] should have let the agony of … kill [him] long since” (367), equating his vitality with that of these workers, painting a bleak picture of his situation. Mossman’s article states that “Wilkie Collins’ engagement with the abnormal [or disabled] body is often defined by a larger kind of anxiety” (486), an anxiety perpetuated by “Blossom and Blight” as the feebleness of an old man is so closely associated with death. By putting this text so close to The Moonstone, the image of Jennings’s weakened body that “tell[s] … the story of some miserable years” (Collins 367) and appeals to readers in the same way it “[makes] some inscrutable appeal to [Franklin’s] sympathies” (356), feeds into the wider anxiety of people in real Victorian workhouses who could see themselves in Ezra’s character, and fear that they are similarly doomed by their situation. It is because of this connection between the real and the fictional that the British version of The Moonstone cannot be read in the same way as the American publication as it treats Ezra as a sympathetic part of the Victorian population. That being said, while All the Year Round does draw pity to his character, there are also elements of it that are less kind to Ezra, and instead of drawing focus to what is wrong with the grueling nature of the Victorian workforce, it alleviates higher-class anxieties of illness through advertisements that highlight Ezra’s identity as something that the higher-class would want to cure.

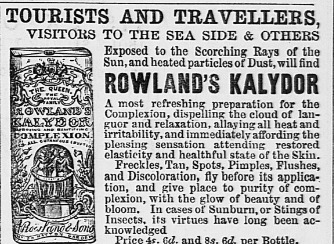

The connection between All the Year Round and its focus on illness extends into its advertisements, which influence readings of Ezra Jennings as someone who the upper echelons of Victorian society would want to cure. With this advertisement for Rowland’s Kalydor, a medicinal cream that claims, "Freckles, Tan, Spots, Pimples, Flushes, and Discoloration, fly before its application," All the Year Round appears to criticize blemishes of the skin. Because it includes tan or “discoloured” skin as an illness–a skin type that Franklin makes a point of noting as part of Ezra’s “gipsy complexion” (Collins 356)–Ezra Jennings is thus categorized as violating the Victorian social order (Glendening 296) that favours paler likenesses. Evidence of Ezra defying this standard appears when Franklin explicitly notes that all of the elements of his face that make him “strange” in his eyes are “calculated to produce an unfavourable impression of him on a stranger’s mind” (Collins 356), and is proved when one of Mr. Candy’s servants receives him with avoidance, “I [Franklin] observed that the pretty servant girl–who was all smiles and amiability, when I wished her good morning on my way out—received a modest little message from Ezra Jennings … with eyes which ostentatiously looked anywhere rather than look in his face” (356). By placing this advertisement after a section of text that negatively emphasizes at how Ezra’s body is treated with contempt because of his skin colour and frailty, it portrays his “abnormal body” as “deviant … that [seems to] plague the body of [Victorian] society” (Mossman 486), and offers a solution to the “problem” that is associated with Ezra’s physical form. Even though this advertisement is less sympathetic to Ezra than “Blossom and Blight,” the fact that they both appear in All the Year Round and concentrate most heavily on how illnesses and the ways they affect Victorian society still differs from Harper’s Weekly, which mostly focuses on race and tries to paint Ezra in that purely negative light.

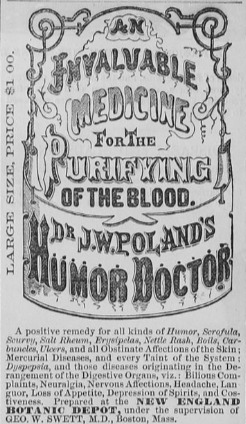

This advertisement for J. W. Poland’s Humor Doctor in Harper’s Weekly impacts readings of Ezra Jennings by specifically targeting the topic of blood purification, which is heavily–and harmfully–entangled in his status as a mixed-race character. While the Rowland’s Kalydor advertisement focuses on how Victorian beauty standards would make Ezra’s character seem ill, this Humor Doctor presents a different Victorian idea that being born of a race other than white would be something to suffer from. Glendening poses the idea that “Jennings's appearance is calculated to be especially distasteful to anybody fearful that “pure” English blood might become polluted by foreign racial elements” (296), and when the context of this advertisement is applied to this character analysis, this advertisement seems to be offering a preventative measure or cure for the “polluting” of the blood. It makes it so that Ezra, who is a character generally rooted for because he is assisting Franklin Blake’s investigation, becomes feared by the Victorian audience because he could be “contaminated” and in need of this Humor Doctor. This is not helped by Franklin’s description of Ezra, which draws on how he is portrayed as suffering in the above illustration from the same periodical, “He had suffered as few men suffer; and there was the mixture of some foreign race in his English blood” (Collins 359), contributing to the idea that his cultural hybridity would not be sought after by Victorian audiences. The implication that his blood would even need purifying in the first place paints a harsher image of his character than the British advertisement because the problem of Ezra’s afflictions is not what is being targeted by the context of the Humor Doctor. Instead, it perpetuates racial stigmatization of hybridity as “wrong” by implying that something deeper is wrong with the character. Even the formatting of this advertisement is more hostile than in the British version, with the gothic-like font and block letters grabbing attention because of how much space they take up, where the Kalydor advertisement is written in a smaller and plainer font. For these reasons, the All the Year Round and Harper’s Weekly publications of The Moonstone cannot be read as the same text because of how they differ in their depictions of race and illness.

Conclusion

So what does all of this mean when applied to The Moonstone as a whole? By having the two of these publications focus so heavily on how Ezra Jennings does or does not fit into Victorian society, avenues of analysis are opened into how Ezra and his character or ailments can be compared to those of other characters in defiance of Victorian norms of abled bodies, race, or class expectations. Ezra’s illnesses in this specific section of the text can be contrasted to Mr. Candy, who is purely sympathetically treated because of his memory loss, but also because he belongs to the white upper-class and is treated as such by the characters in his employment. Meanwhile, Ezra becomes a topic for debate and anxiety because his natural skin colour would have been viewed as contaminated or ugly because the Victorians value paler complexions and fear how his addictions and frail frame bring him closer to death. He can also be compared to characters such as Rosanna Spearman or Limping Lucy in earlier chapters of the novel. Because of their lower social standings, imposed mainly by their disabilities, the three characters become connected by how they would be viewed by Victorian audiences, as people with conditions that able-bodied and upper-class persons would fear, and want to cure so they would not disrupt their order.

Works Cited

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone. Oxford University Press, 2019, pp. 356-369.

Glendening, John. “War of the Roses: Hybridity in ‘The Moonstone.’” Dickens Studies Annual, vol. 39, 2008, pp. 281-304. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/44372199.

Mossman, Mark. “Representations of the Abnormal Body in ‘The Moonstone.’” Victorian Literature and

Culture, vol. 37, no. 2, 2009, pp. 483-500. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40347242.