Part 23 - Faoja Chowdhury

During a period of rapid advancements in print, society, and politics, editorials and publications naturally reflected their era—and Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone was no exception. Tied to orientalist roots and mystified by exoticism, The Moonstone follows the complicated case of the stolen diamond—the Moonstone, an ancient Brahmin jewel steeped in secrets and danger. The third narrative, told by Franklin Blake, not only reveals a crucial piece of information regarding his involvement in the heist through the letter of the recently deceased Rosanna Spearman, but also introduces Ezra Jennings, whose partially foreign parentage and Eastern features amplify the exoticism imbued within The Moonstone. Victorian exoticism, defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as “something with foreign origins” or the enchantment with foreign or “unusual” things (“Exoticism, N.”), was shaped by colonialism and its portrayal of ‘otherness.’ As Petr argues, exoticism served as a colonial justification, emphasizing the strangeness of ‘the other’ to instill fear or a subtler fascination that may elicit feelings of wanting to dominate a ‘mystical’ unknown (2). This duality is evident in The Moonstone’s surrounding publication contexts: in Charles Dickens’ All the Year Round and America’s Harper’s Weekly. In the British publication, Ezra Jennings’ introduction and his Eastern traits are portrayed with a cautionary tone, echoing fears of the unknown to justify racial superiority. In contrast, Harper’s Weekly oscillates between fascination and superiority––for its illustrations and articles evoke empathy while simultaneously reinforcing colonial hierarchies through quieter means. Both approaches subtly endorse colonialism, albeit through different lenses—All the Year Round using fear of the unknown, and Harper’s Weekly blending intrigue, sensationalism and imperialistic undertones. This complex interplay is particularly evident in Franklin Blake’s fourth chapter, where Jennings’ depictions embody Victorian exoticism’s conflicting facets.

Beginning with its origins in Britain, one of the novel’s publications appeared in the British periodical, All the Year Round, edited by Charles Dickens. Surrounding chapter four of Franklin Blake’s narrative, the accompanying articles provide a prejudiced context to its reading that deeply reflects the exoticism and racial superiority prevalent in Victorian society––especially one titled, “The Imposter Mege.” Following a curious Caliph and cunning Dervish, this article uses their tale as a comparison to the case of the de Cailles, a French family also startled by a strange ‘resurrection’ of their deceased son––believing an imposter to have taken his identity. In this regard, the short story presented at the beginning of the article serves as a cautionary tale of magic and manipulation––stereotypical associations with the East. The Dervish, as the story goes, possesses the ability to “[throw] his own soul or spirit into any inanimate creature, thereby restoring its life” (615), however, his own body would fall lifeless until the moment the soul returns; he demonstrates this by reviving a dog. The Caliph persuades the Dervish to teach him the method––however, when he experimentally transfers his soul into the dog, the Dervish steals into the Caliph’s unoccupied body and lives his luxuries. Framed as a cautionary tale, this narrative links Eastern mysticism with deceit and manipulation, setting a tone of unease before introducing Ezra Jennings in The Moonstone. This context becomes significant as Jennings is described with “gypsy darkness” and features resembling “the ancient people of the East” (Collins 575), which aligns with Victorian stereotypes of foreignness and mysticism, particularly through terms like “extraordinary,” “dreamy,” and “captivating” (Collins 575). Up to this point, The Moonstone has portrayed foreigners either as enigmatic figures like the Brahmins seeking to reclaim the diamond or as gentlemanly characters like Mr. Murthwaite. Placing “The Imposter Mege” before Jennings’ introduction primes Victorian readers to associate his character with suspicion and ‘otherness.’

The next article appearing in Dickens’ All the Year Round, titled “Ague and its Cause,” is especially startling in its placement––for it follows immediately after the introduction to Ezra Jennings in Franklin’s chapter four. It begins, “that of fen places come malaria, and that of malaria comes ague” (606), before describing its dangerous attributes and origins. As an air-borne, sporous disease, it is described as “poison”––a pestilence that was “common” and “dangerous” in England especially (607). Upon first glance, this article detailing this dangerous “marsh fever” may seem irrelevant to the fourth chapter of Franklin Blake’s narrative in The Moonstone––however, it holds deeply negative connotations due to its immediate placement following Jennings’ character introduction. The article says, “the wetter the season and the hotter, the better it is for malaria” (607), before directly referencing India––the country Jennings has blood ties to. Similarly, malaria is a disease carried by mosquitoes commonly found in South Asia. Evidently, the negative connection is immediately brought to light––as if the publication is attributing a tainted blood disease to Jennings merely for his mixed heritage. This section of Franklin Blake’s narrative especially presents Jennings to be a character worthy of suspicion, for when Franklin questions the reason behind Jennings’ notoriety, Betteredge says, “[Jennings’] appearance is against him [...] Mr. Candy took him with a very doubtful character [...] nobody knows who he is” (Collins 577). Immediately, before Jennings can speak, he is cast under suspicion for his appearance and alienated simply for his heritage; he is essentially “othered.” To a Victorian audience, the disdain for his character is further instilled through “Ague and its Cause” for its relation to India and its perhaps metaphorical interpretation––for many immigrants during the Victorian period may have also been considered a “common pestilence,” regarded with disgust. In this way, exoticism is weaponized against Ezra Jennings to “other” him––a tool to justify colonialism by instilling fear within Victorians––for Ezra Jennings ultimately passes away at the end of the novel, as if a “poison” was cleared, potentially lessening the empathy of readers of All the Year Round.

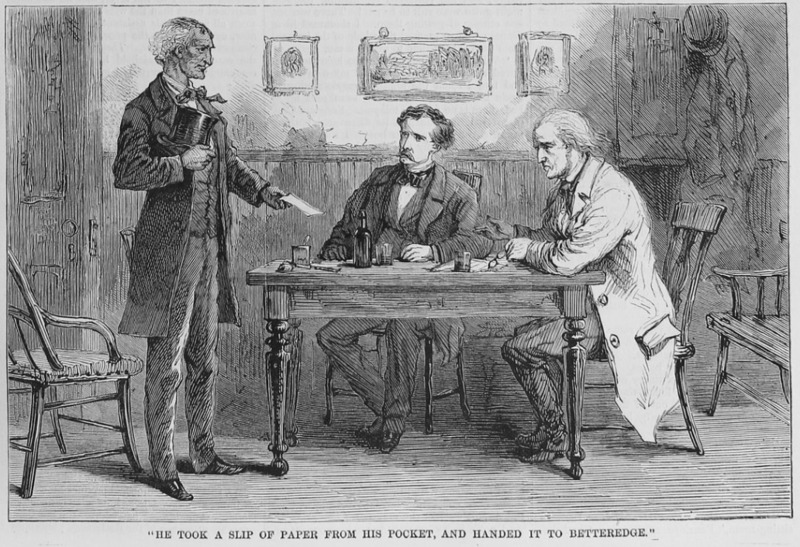

In the American Harper’s Weekly, the second publication of The Moonstone presents an alternative interpretation of Jennings’ portrayal, leaning into darker connotations. The American fascination with his character may not stem from genuine respect, but rather a fascination with the spectacle of his ‘otherness.’ In this section of Blake’s narrative, the largest, most distinct illustration depicts Jennings’ first appearance. Captioned, “He took a slip of paper from his pocket and handed it to Betteredge,” Jennings appears as the novel suggests: darker skin, untrimmed white hair on the sides, and a slightly hooked nose––traits associated with the Indians of the East. While Jennings is depicted as well-dressed and refined, this depiction may reflect the curiosity of a society that may have viewed people like him, particularly those with mixed blood, as exotic curiosities. Franklin’s observation of Jennings’ curled, colorless hair as “some freak of nature” (Collins 575) reinforces this idea of him as an anomaly, both intriguing and strange––especially through terms such as “extraordinary” and “captivating” (Collins 575) Blake uses to describe him. By emphasizing Jennings’ physical differences, the illustration could be seen as turning him into a spectacle, reduced to something for “European consumption”—an object of fascination rather than a fully realized character (Jenkins 2), especially when Franklin says, “I looked at the man with a curiosity [...] impossible to control” (Collins 576). The illustration, therefore, might not simply present Jennings as a person of dignity but as a curious, almost ‘exotic’ figure. His presence positions him as a spectacle that reflects colonial attitudes toward race and culture. Thus, Jennings’ character depiction may be interpreted as a spectacle in Harper’s Weekly—an object for consumption, as Jenkins mentions in her article, revealing the complexities of Victorian racial attitudes that mixed both fascination and dehumanization, doubtlessly influencing a reader’s interpretation.

The sensationalism of those of the East is especially prominent in the article titled, “Popular Zoological Errors,” which comes immediately before Franklin Blake’s fourth chapter of The Moonstone. Commenting on the preposterous misinformation regarding the hedgehog and the toad, this short article, in its placement, seems to be a direct confrontation of Betteredge’s prejudiced views of Jennings. For instance, the article often uses terms such as “strange superstition” and “absurd notion” (356) to describe the false stereotypes associated with the hedgehog and the toad, using logic to debunk them; similarly, throughout Jennings’ short journey in The Moonstone, the narrative debunks the suspicions associated with him, rather offering him a more empathetic lens that may provoke sympathy within Victorian readers when he passes away. This reading would rather draw attention to Jennings’ more attractive descriptions, like his dreamy, soft brown eyes (Collins 575). The toad’s description may especially connect to Jennings, for its mystical superstition regarding “magical powers” (356), just as how Indians were associated with magic, as well as the magical preserved stones from toad heads from “ancient times” (356), falling in with Jennings’ description of having features akin to those of “the ancient people of the East” (Collins 575). However, this connection to animals––especially magical ones––further exoticizes Jennings, sensationalizing his character as if he, too, is a strange, mystical creature that “no one knows [...]” (Collins 577), as Betteredge implies, adding to the “entire mythology of ‘the world’” (Jenkins 2). The placement of this article doubtlessly impacts its reading––for although it elicits fascination within its viewers, it reduces Jennings’ character to a spectacle for viewer consumption––thus holding subtler negative connotations.

In closing, the publication contexts of All the Year Round and Harper’s Weekly offer contrasting interpretations of The Moonstone, shaped by the racial and colonial attitudes prevalent in each. Chapter four of Blake’s narrative is pivotal in revealing key details about the stolen diamond, implicating both Blake and Jennings. The introduction of Jennings, a tragic and sincere character, highlights the novel’s engagement with issues of race, especially in how foreigners are portrayed. Depending on the periodical, the representation of these characters can vary significantly, influencing readers’ perceptions of the novel and its foreign figures, such as the Brahmins, Mr. Murthwaite, and Jennings. In All the Year Round, the depiction of these characters aligns with a more cautionary tone, casting them as suspicious, even villainous, figures. The Brahmins, for example, are presented as sinister despite the violence done to them at the novel’s outset. This emphasis on fear and otherness aligns with the racial attitudes of Victorian Britain, reinforcing colonial notions of superiority and difference. In contrast, Harper’s Weekly offers a more complex portrayal, especially of Jennings, whose mixed heritage is both intriguing and unsettling to the American audience. While the illustrations make him appear more dignified, the fascination with his “otherness” suggests a deeper, more troubling colonial perspective. Jennings’ portrayal as both refined and exotic highlights the tension between admiration and condescension, reflecting the mixed fascination and dehumanization of non-European characters. This portrayal echoes the same colonial ideologies found in All the Year Round, but with a more overt focus on spectacle and difference. Both publications ultimately reinforce colonial attitudes, whether through fear or fascination, subtly shaping readers’ perceptions of race, exoticism, and foreignness. Thus, the periodicals significantly influenced how the novel’s themes of orientalism and colonialism were received, imbuing the narrative with both negative connotations and racialized readings.

Works cited

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone. E-book Ed., Oxford University Press, 2019.

“Exoticism, N., Sense 2.” Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford UP, July 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/6762089905.

Jenkins, Eugenia Zuroski. “Introduction: Exoticism, Cosmopolitanism, and Fiction’s Aesthetics of Diversity.” Eighteenth-Century Fiction, vol. 25, no. 1, 2012, p. 1–7, https://doi.org/10.3138/ecf.25.1.1.

Petr, Christian. “Towards Modern Exotic Literature.” Journal of European Studies, vol. 29, no. 1, 1999, pp. 061–65, https://doi.org/10.1177/004724419902900107.

Unknown Artist. Harper’s Weekly: A Journal of Civilization, 6 June 1868, p. 357, print.

Unknown Author. "Ague and its Cause." All the Year Round. 6 June 1868, p. 606-610, Chapman & Hall, print.

Unknown Author. "Popular Zoological Errors." Harper’s Weekly: A Journal of Civilization, 6 June 1868, pp. 356, print.

Unknown Author. "The Imposter Mege." All the Year Round. 6 June 1868, p. 615-618, Chapman & Hall, print.