part 21- Madeeha Umar

Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone, is published in serialized installment in Charles Dickens’ All The Year Round and Harper’s Magazine. Chapter 1 of the third narrative follows Franklin Blake as he returns to England and seeks Rachel out. This chapter is characterized by Franklin’s pursuit of Rachel specifically how “irresistibly her influence began to recover its hold on [Franklin]” (Collins 283). However, the stolen moonstone “remains an unpardoned offence” (Collins 285) in Rachel’s mind, reflecting the tension between materialism and relationships. This tension is further complicated by the cultural context of The Moonstone’s serialization in All The Year Round and Harper’s Magazine that represent a concern with status.

The original publishing context is highly relevant in controlling the way the novel is read as evident in Koenraad Claes’ article, “Supplements and Paratext: The Rhetoric of Space” which claims that periodicals must be studied as part of a larger web of contemporary contexts, rather than being treated as independent literary texts (198). While Claes emphasizes the reader's ability in constructing meaning from the fragmented periodicals, this paper extends his argument to directly study how a single chapter can be read differently depending on a publishing context. Moreover, this paper argues that by reading the periodicals along with the environment it exists in, it serves to also describe contemporary social outlook on love. Through comparison of both All The Year Round and Harper’s Magazine’s articles and advertisements, this paper will complicate the representation of relationships in The Moonstone. Through its publicization in All The Year Round and Harper’s Magazine, The Moonstone reflects differing cultural attitudes toward the intersection of relationships and status in Victorian Britain and Victorian America.

In All the Year Round by Charles Dickens, The Moonstone is presented along with various other articles and short stories. “Shakespeare and Terpsichore” is a review of William Shakespeare’s works, Romeo e Giuletta, otherwise known as Romeo and Juliet in English, and A Midsummer Night's Dream, that are adapted into various art forms of a tragic opera and grand ballet. The adaptations serve to elevate Shakespeare’s works and position him among the popular culture in the Victorian Era. By placing this article in the same installment as The Moonstone, Dickens elevates Collins’ work in a similar way, suggesting that it is also worthy of cultural prominence just as Shakespeare’s plays.

This allows readers to compare this chapter to the works of Shakespeare such as Romeo and Juliet. All The Year Round appeals to those who appreciate Shakespeare’s plays and implicitly frames The Moonstone as containing high emotional stakes and complex relationships by associating it indirectly with Shakespeare. Franklin, who is deeply in love with Rachel, and Rachel who denies seeing Franklin because the stolen moonstone “remains an unpardoned offence” (Collins 285) in her mind, parallel the tragic lovers Romeo and Juliet who desire to be together but are unable to. This framing of The Moonstone elevates the story beyond domestic drama and instead engaging with themes of love, fate, and personal sacrifice.

As the review continues, the unknown author alludes to details in Shakespeare’s plays that implies a certain level of cultural literacy among the readers. For instance, “Desdemona” and “Lady Macbeth” are referenced without extensive explanation suggesting that readers possess the education necessary to understand the allusions. Ultimately, All The Year Round frames the relationships in The Moonstone as not just an entertaining domestic drama, but as a form of high culture, with love itself positioned as something worthy of cultural significance and status.

In the American Harper’s Magazine, the publication of The Moonstone appears among advertisements and news articles, including one titled “What We Love a Woman For.” This advertisement lists articles such as “That Horrid Little Fright”, and “How to Make Paper Flowers” (“What we Love a Woman for” 334). Claes suggests that “Authors, illustrators, editors, publishers, and readers all affect what a publication will look like” (198) and therefore, this advertisement is a product of collaborative decision-making that reflects the cultural values and expectations of its readership. The placement of The Moonstone alongside domestic articles reflects deliberate editorial decisions that situate the novel within a heteronormative view of relationships and where a woman's worth lies in her ability to self-improvement and perform to gain the affection of a man.

This prompts readers to consider why Franklin might love Rachel and if Rachel fits into the Victorian ideal woman. If an “upper-class woman's primary function was to display... her husband's wealth” (Cruea 189), Rachel does not fit into this mould. As Rachel inherited money after her mom passed (Collins 266), her wealth positions her outside the typical role of a woman who is entirely defined by her relationship to a man’s wealth. Although Franklin romantically pursues Rachel, when she “decline[s] entering into any correspondence with Mr. Franklin Blake” (Collins 284), this highlights her agency. This shift underscores the tension between romantic ideals and status in The Moonstone because Rachel’s wealth allows her to access power otherwise unavailable to women. Harper’s Magazine not only reinforces the idea that a woman's worth is defined by her ability to please others, but it also highlights the tension between this societal expectation and the ways in which characters like Rachel defy those very limitations. This contrast redefines The Moonstone, shifting it from a mere romance to a critique of gender roles, highlighting the complexity of relationships and the novel's engagement with female agency.

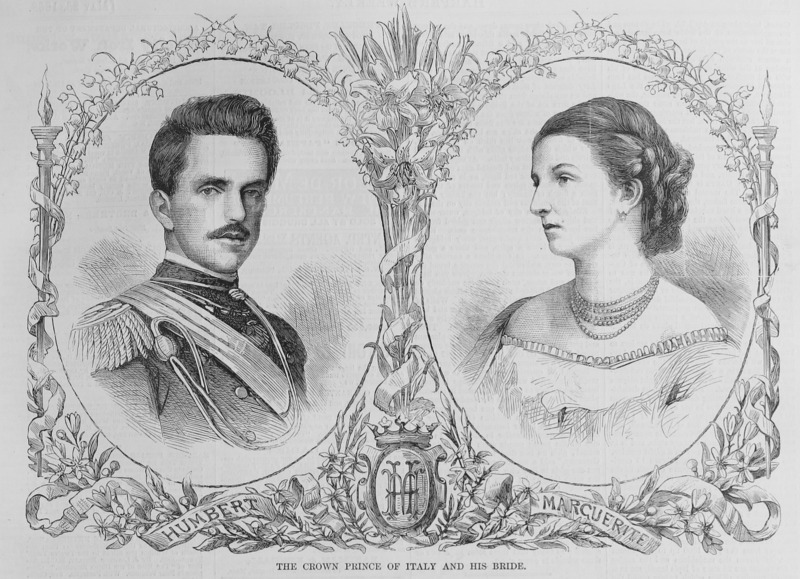

Included in Harper’s Magazine is a marriage announcement of “The Crown Prince of Italy and his Bride.” The placement reflects how spatial organisation is a reflection of editors who try to “anticipate the expectations of their…readership” (Claes 203). That is to say, this positioning—how and where information is placed—reflects editorial decisions that mediate between the periodical’s core themes and the reader’s anticipated interests. Building off of this, Harper’s inclusion of this image frames marriage within a broader cultural narrative that prioritize lineage and social power. Without a monarchism, “America substituted wealth for bloodline” (Cruea 189) which creates an ongoing tension with status and marriage. This sketch of the couple is two separate images that omits affection. This prompts questions regarding the potentially transactional nature of this marriage. However, Franklin and Rachel’s relationship contrasts the apathetic illustration presented in Harper’s Magazine. Rachel and Franklin spent their early relationship doing “decorative painting” (Collins 49) and moments where they “never seemed to tire of [spending time together]” (Collins 50). The editor’s choice to depict the aristocratic union in a apathetic nature suggests that social status and family lineage overshadow genuine love. Harper’s suggests that relationships are framed within the context of societal expectations reflecting that matrimonial unions are not about affection, but also about securing status, wealth, and social power.

In this illustration, both the husband and bride are depicted in wearing high class clothing such as a suit and the bride with pearls. Considering how a woman’s role was “to reflect her husband's wealth and success” (Cruea 190), this is evident in the bride's jewelry. However, Rachel’s inheritance gives her an independence from depending on a man for money that challenge this conventional view. This illustration highlights the tension between romantic ideals and societal norms in The Moonstone, where relationships and wealth intersect but are not always aligned in the way the societal expectations would suggest.

Harper’s Magazine features a poem “I’d Be a Farmer’s Wife” is written from the perspective of a seventeen year old girl who has a desire to marry a farmer and life a simple “country life.” The emphasis on the joy of living with nature creates a sense of rural nostalgia which stands in contrast to the rapid industrialization of the period (Cruea 190). This juxtaposes Rachel who is intertwined with the moonstone, inheritance, and material wealth. While farmer’s wife falls in love with “the country-life” and not a man, Rachel’s marriage is potentially rooted in genuine affection for Franklin.

Initially, Rachel’s wealth makes her a commodity in a system of social and material exchange that attracts suitors like Godfrey Ablewhite who are only after her wealth. Thus, Rachel is forced into the symbolic position of a man who is the provider which defies forces a reconsideration of a woman’s worth especially considering her status. When Rachel considers marrying Godfrey, she is “marrying in despair…on the chance of dropping into some sort of stagnant happiness” (Collins 262). However, in a later conversation between Franklin and Rachel where she admits she “was thinking of [Franklin],” these words go “straight to [Franklin’s] heart” and “almost unmanned him” (Collins 335). Rachel does not need to marry for wealth or status, she marries Franklin on her own terms. In contrast, the girl in the poem is not described as wealthy and her desire for marriage is to fulfill her love for the countryside rather than survival or affection for a man.

While Victorian standards would have encouraged women to marry “hardworking, compassionate, and moral [men] rather than one who was merely wealthy or physically attractive” (Cruea 193), Harper’s presents the existence of a woman who defies this by following her passion of nature and farming. However, despite such freedom of choice, this limits her to being a “wife” (“I’d Be a Farmer’s Wife” 331) and not a farmer herself. Moreover, while women have a choice, they are limited in it and Harper’s publication explores the limited choices women face, where personal desires coexist uneasily with societal constraints.

The serialized publication of The Moonstone in All The Year Round and Harper’s Magazine underscores the significant role periodicals played in shaping Victorian readers’ interpretations of literature. Building on Claes' assertion that a publication “strengthens a clear profile for [its] ideal readership” (206), both periodicals curated content that resonated with their specific audiences. All The Year Round appealed to educated British readers, interested in high culture literature and complex social themes. Moreover, this is emphasized in the lack of images or advertisements. In contrast, Harper’s Magazine catered to a broader American audience, focusing on social changes and gender roles as evident through advertisements, reviews, and poems.

By placing The Moonstone alongside a Shakespearean adaptation, All The Year Round elevates Collins’s work, framing it as part of a cultural canon that examines love, sacrifice, and fate. This editorial decision highlights the universal and timeless elements of Rachel and Franklin’s love story, aligning it with narratives of high emotional stakes. Conversely, Harper’s Magazine situates The Moonstone within a domestic and material framework, pairing the novel with articles that reflect societal expectations of women and marriage. This positioning critiques the transactional nature of Victorian relationships while contrasting Rachel’s defiance of these norms. Rachel’s socioeconomic class gives her independence and the choice to marry for love which suggests that woman’s freedoms are also dictated by status and wealth. Although Claes' article argues the significance of paratext in shaping readers' engagement and understanding of texts, The Moonstone demonstrates how serialized publications like All The Year Round and Harper’s Magazine use paratext to position the novel within different cultural and social contexts.

Works Cited

Claes, Koenraad. “Supplements and Paratext: The Rhetoric of Space.” Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 43, no. 2, 2010, pp. 196–210. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25732104. Accessed 7 Dec. 2024.

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone. Oxford University Press, 2019. Print.

Cruea, Susan M. "Changing Ideals of Womanhood during the Nineteenth-Century Woman Movement." American Transcendental Quarterly, vol. 19, no. 3, 2005, pp. 187-204,237. ProQuest,https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fscholarly-journals%2Fchanging-ideals-womanhood-during-nineteenth%2Fdocview%2F222378111%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D9838.

“I'd be a Farmer's Wife.” Harper’s Weekly. 23 May 1868, p. 331. Gale Primary Sources. https://go-gale-com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/ps/navigateToIssue?volume=12&loadFormat=page&issueNumber=595&userGroupName=ucalgary&inPS=true&mCode=96EY&prodId=AAHP&issueDate=118680523.

“Shakespeare and Terpsichore.” All the Year Round. 23 May 1868, p.565. Gale Primary Sources. Dickens Journals Online, https://www.djo.org.uk/all-the-year-round/volume-xix/page-565.html.

“The Crown Prince of Italy and His Bride.” Harper’s Weekly. 23 May 1868, p. 334. Gale Primary Sources. https://go-gale-com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/ps/navigateToIssue?volume=12&loadFormat=page&issueNumber=595&userGroupName=ucalgary&inPS=true&mCode=96EY&prodId=AAHP&issueDate=118680523

“What We Love a Woman For.” Harper’s Weekly. 23 May 1868, p. 334. Gale Primary Sources. https://go-gale-com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/ps/navigateToIssue?volume=12&loadFormat=page&issueNumber=595&userGroupName=ucalgary&inPS=true&mCode=96EY&prodId=AAHP&issueDate=118680523.