Part 11 - Alexandra Denton

Wilkie Collins released two considerably different versions of the same serialized novel, Moonstone. One, more serious and ‘literary’ in the British market. Charles Dickens’ “All the Year Round”. This British version, created by the well known and successful English author himself, had a much more focused spread of fiction and non-fiction stories. The other, published in the American market, contained illustrations, single panel comics, newstories, and comedy sections. The illustrations in “Harper's Weekly” are representative of how overall, the American version of Moonstone needed to be an even more spectacularized version of an already sensational story. It had to elevate the story past just being a novel like its British counterpart. It needed to do this for two reasons. Firstly, for the sake of “Harper’s Weekly” paper’s ability to survive financially, as is argued by Lisa Surridge and Mary Elizabeth Leighton in “The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper's Weekly”. And secondly, due to the competition of entertainment within the overly saturated “Harper's Weekly” newspaper itself.

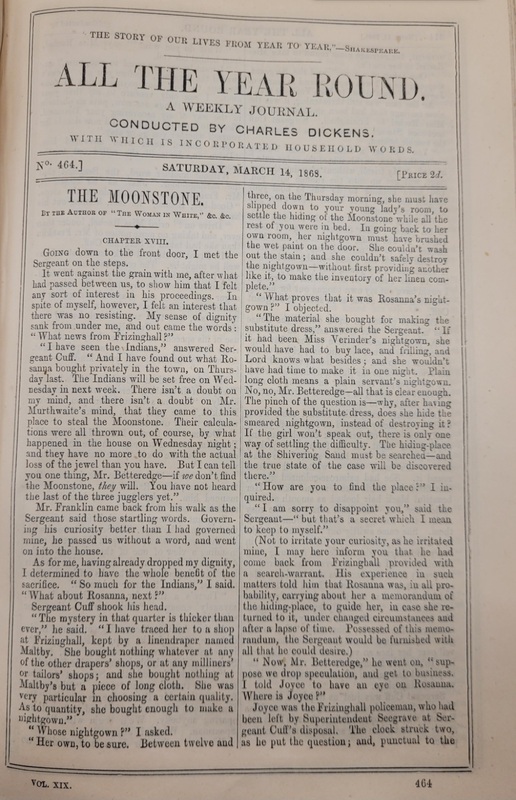

Wilkie Collins was an Englishman, and he was a smart businessman to diversify and publish with both the British and American markets. But, the “All The Year Round” version would be the publication he and his closest friends and peers would have easiest and quickest access to. As is seen in the image above, this version of Collins Moonstone is very similar in both appearance and structure to a novel that one would see today. The page itself is small, about one sixth of the first page of chapter XVIII is being taken up by headings. There is nothing that breaks up the page, no highlighted quotes from the story. It is a continuous text. This suggests that “All The Year Round” had faith in the novels it serialized to attract readers completely on their own, simultaneously, (consciously or unconsciously), showing trust and regard towards the literature itself. The line at the very top of the page, acting as a motto, reinforces this idea. Stating, “The Story of Our Lives From Year to Year” (All The Year Round 464). This being a paraphrased quote from Shakespeare's Othello. This quote immediately gives the newspaper a sense of literary appreciation, suggesting almost that what you are about to read would be approved by the bard himself. This suggests to potential buyers that while yes, this is still a serialized newspaper novel, they are also offering you the best of the best of such. The title of the novel is underneath the heading in slightly larger font than the rest of the body text, but the author listing found underneath is the same size as it. Interestingly, Wilkie Collins name is not even directly credited. Instead, “All The Year Round” simply lists it as “[b]y the Author of “The Woman In White,” &c. &c.” (All The Year Round 464) This implies that “All The Year Round” has enough faith in Collins to be known by his works alone, and that his name does not need to be listed for potential readers and buyers to be interested. Reinforcing the idea that “All the Year Round” is purely a literary publication. Readers coming to it for the work, not the name of the author.

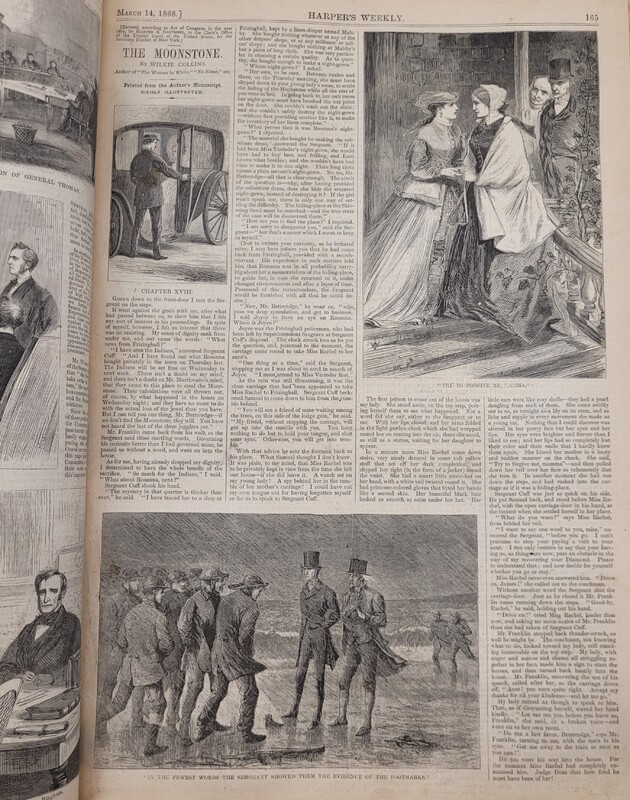

“Harper’s Newspaper” differs not only in the way it lists Wilkie Collins as the author, but in many other drastic ways as well. As is argued by Lisa Surridge and Mary Elizabeth Leighton in their article, “The Transatlantic Moonstone : A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper's Weekly”, “Collins… unleashed in America a notably different version of his novel.” (Leighton and Surridge 23) In “Harper’s Weekly”, Wilkie Collins name is blatantly stated underneath the title of the novel. And, similarly to the “All The Year Round” version, so is the fact that he authors “The Woman in White”. But “Harper’s Weekly” also adds onto this, listing “No Name” as one of his works. Another difference, as can be seen in the image above, is the stark contrast of the page size of “Harper's Weekly”. Instead of being similar in size to a novel like its English counterpart, it is more akin to the standardized, very large, page size we associate with newspapers still today (consistent in the west for centuries). This is a necessary difference considering that more than half of the title page for Chapter XVIII is taken up by illustrations, acting as the starkest difference between the two serialized versions. All of these differences could be attributed simply to the fact that there is a difference between American and British audiences, and that while they both desire sensationalism and mystery, the American audience wants it to be exaggerated. And while that may be true, it is also known that “Harper’s Magazine’s sales slumped at the end of the Civil War” (Leighton and Surridge 208) and that “Collins’s [had a] popularity with American readers” (Leighton and Surridge 208). So by giving readers multiple ways to recognize him (by his name and by his works), and by using illustrations to further intrigue and sensationalize they would be able to acquire and assure returning readers, or also, returning purchases. They used Collin’s as a way to secure buyers, but then they needed to ensure they would return to buy the next installment. That is where we see illustrations utilized.

These illustrations are able to add a whole other level of storytelling to this novel, in a way that makes it basically an entirely different work than the British version. Surridge and Leighton discuss exactly how these illustrations elevate and sensationalize, stating that “[t]he illustrations heighten the text’s sensationalism and complicate its narrative scheme with iterative patterns, analeptic scenes, extradiegetic and alternative points of view, as well as with rich interpictorial relationships.” (Leighton and Surridge 222) For example, the illustration above comes from Chapter XVIII of the “Harper’s Weekly” Moonstone. The illustration depicts Rachel and her Mother, standing distressed. They are atop of the steps of the house which depicts the rising tension of the scene and the coming descent of the character as she flees after the moonstone has been stolen. While the specifics of the scene are mentioned in the text, the illustration is also accompanied by a quote. The line, quoted from text on the same page as the illustration reads, “Try to Forgive me, Mamma” from a conversation between Rachel and her Mother. The quote in combination with the illustration creates a whole separate form of entertainment from the novel itself. The panicked expressions of the women and the men standing behind them (something which is not directly mentioned in the text for most of the characters depicted), the overall darkness of the illustration, it allures. If a reader was flipping through their copy of Harpers and saw this illustration they would be left with many questions, why do these women look upset? Who are the men with puzzled expressions in the shadows watching them? And why does the daughter need her mothers forgiveness as mentioned in the quote? These are the sort of questions and intrigue that would encourage potential new readers to tune in, and help to emphasize and promise further mystery and excitement for those already reading.

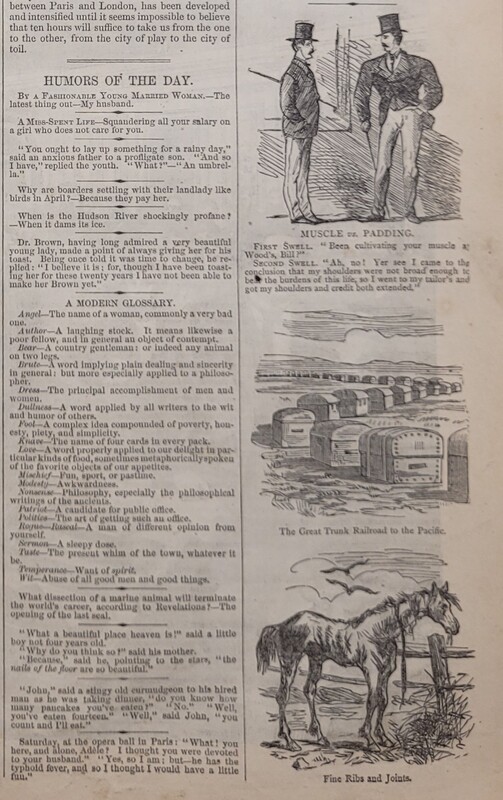

These illustrations and the promise of what they add to the story is vitally important. Yes, Moonstone itself is already a sensational story. And, Wilkie Collins was a well known and appreciated author that could draw readers on his own. However, “Harper's Weekly” presents a challenge within itself that is not seen in a publication like “All The Year Round”. Just like “Harper’s Weekly”, “All The Year Round” also has other stories printed within it. In Dickens' publication they are all simply textual, appearing the same upon first glance, nothing except context to distinguish them from one another. However, as aforementioned, “Harper's Weekly” contains other content, as can be seen printed on the last page of chapter XX of Moonstone in the image above. Alongside the chapters from this section, there are other things illustrated. Specifically here we see what is comparable to a ‘the funnies’ section in modern day newspapers. There are several illustrated jokes such as a joke about “Muscles vs. Padding” (Harper’s Weekly 167), and an ironic illustration of a skinny horse titled “Fine Ribs and Joints” (Harper’s Weekly 167). Next to these, (seen on the top left of the image above), is also a list of “Humors of the Day” (Harper’s Weekly 167), these are just a couple examples of the various items that could be found in “Harper's Weekly”. These comedy items and illustrations, other articles (both opinion and news based), other stories found in the paper, and advertisements, are all directly competing for the reader's attention. In “All The Year Round”, the stories simply have to compete with the other stories being published, but here, there are many other things for the reader to get distracted by. This is just one more reason why the illustrations in Moonstone would need to be sensational, it would be required in order to keep readers focused and happy with the story they are currently focusing on as entertainment. Yet, it is not clear if this is a boon or a bane to the overall quality of the novel, as one could argue this lessens the reader’s ability to take the text seriously as a piece of literature, as it is more such the presentation in “All The Year Round”.

Despite being published in tandem, the American and British Moonstone’s are definitely not the same text. Being published in two different markets, with different competition, the American version found itself needing to differentiate itself within its own market. Something like Chapters 18, 19 and 20 in Moonstone would be far enough along that readers are likely committed, and it would be harder to get someone to start reading anew at that point. That is why something like sensational illustration could be such a benefit for keeping and drawing readers attention. Making the American readers feel like they are receiving extra content to consume, keeping them satisfied and wanting to buy more of their product. And also even potentially being intriguing to get someone to start reading part way through the story. This, ultimately gave “Harper’s Weekly” something to publish to keep the company consistently and comfortably receiving a profit, ensuring they could sell ads and papers, as long as Moonstone was being serialized.

Works Cited

Collins, Wilkie. “The Moonstone Chapter XVIII.” All The Year Round, 14 Mar. 1868, pp. 464

Collins, Wilkie. “The Moonstone Chapter XVIII.” Harper's Weekly, 14 Mar. 1868, pp. 165-167.

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone. Oxford University Press, USA, 2019.

Leighton, Mary Elizabeth and Lisa Surridge. "The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper's Weekly." Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 42 no. 3, 2009, pp. 207-243.