All the Year Round or Harper’s Weekly, American or British: Binaries and False Dichotomies in Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone

Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone appeared in two different publications during its original printing run in 1868: Charles Dickens’s British periodical All the Year Round, and the American magazine Harper’s Weekly. These two publications had very different approaches to their dissemination. Harper’s Weekly included as much razzle dazzle as can be expected of an American magazine, with pictures abounding and many small, entertaining pieces included between their larger works. All the Year Round published solely the writings of its authors, with minimal stylistic frippery. Melissa Free’s article “Dirty Linen”: Legacies of Empire in Wilkie Collins’s ‘The Moonstone’” notes many strains of carefully concealed anti-imperialism rhetoric in The Moonstone, identifying points that indicate the Victorians’ general conviction of British superiority and the divide between what is British (identified as good) and foreign (an othered, pitied bad). This prevalent focus on the dividing factors of class and circumstance is evident in the separation between British and other, British and American, and men and women in Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone. The differences in the publications in which The Moonstone first appeared illustrate these dichotomies in Victorian life, beginning with the potent differentiation between British and American and ending with the separation between masculine and feminine roles.

This first image is taken from the publication of Part 12 of The Moonstone in Charles Dickens’s periodical All the Year Round. As you can see, it is very austere; there are no illustrations and no usage of fancy formatting. There is nothing to distract from the bare bones of the text. This attitude towards the publication of this periodical seems to reflect the sense of British superiority; the underlying implication is that British readers don’t need pictures in order to understand or enjoy a story. As Free says, “English identity was superincumbent, pressing down on that which simultaneously held it up: the subject races, the colonized countries, the ‘foreign’” (340). The story immediately following this segment of The Moonstone cements this idea of British superiority with its treatment of the “Russian peasantry”, othering them into a fascinating oddity for a British audience. In this case, the language used clearly categorizes the Russian peasantry as “foreign”. The author of the piece resorts to Betteredge-isms – or generalizations about people living in countries other than England, reflected in Gabriel Betteredge’s descriptions of the many sides of Mr. Franklin’s personality – at multiple different points, stating “There is also a certain air of restraint – a mingled look of fear and watchfulness – about people, which is especially Russian” (Dickens, 343). The overall impression of the visual appeal of this publication of The Moonstone – or rather, the lack thereof – is that any publications that rely on visual effects to lure in readers as opposed to the quality of the written content are inferior to these true British publications. And the sense of the inferiority of anything non-British is cemented by the stories published within the periodical.

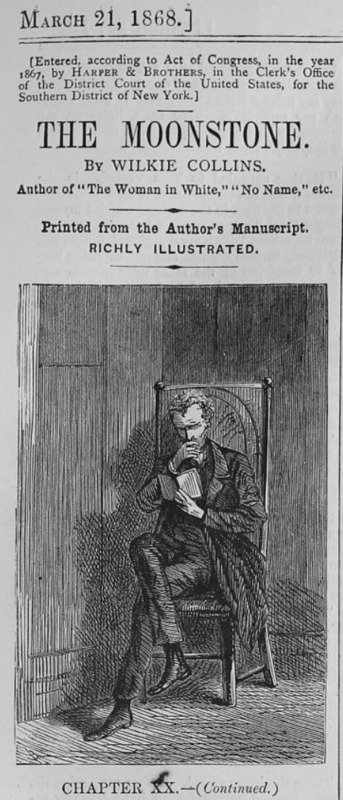

There is an immediate difference in this second image from the publication of The Moonstone in American magazine Harper’s Weekly. This installation of The Moonstone is prefaced by an opening image of Sergeant Cuff in his chair, an image that lures the reader in and creates a visual basepoint off of which their imagination can jump. This is the diametric opposite to the publication of The Moonstone in All the Year Round; the extra content surrounding The Moonstone in the American publication almost seems to be wagging its thumb at its British counterpart. As opposed to a grave presentation of the piece as solely being of literary worth, Harper’s Weekly entices readers in with a byline identifying the author and establishing character with a visual image. Melissa Free states, “Though Collins’s contemporaries were familiar with ‘empire’, they tended to perceive it as something that existed outside of, but not as part of, nation, and his nineteenth-century reviewers – no doubt as a consequence of this belief – did not see The Moonstone as a piece of social criticism” (344). While All the Year Round relied on British arrogance to blind its readers to Wilkie Collins’s social commentary, Harper’s Weekly actively distracts from the anti-imperial aspects of the book with a spectacle in the form of illustrations.

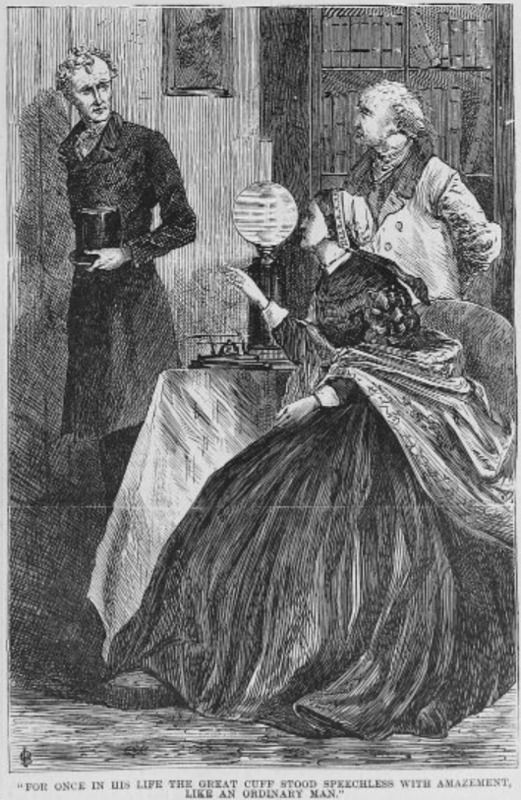

Another dichotomy that is enforced in The Moonstone is that between masculinity and femininity, with an emphasis on female fragility. Women in the Victorian era were confined to a certain sphere that was very difficult for them to quit, that of something othered from men. In the private sphere, women held a significant amount of power over their immediate household. However, only men were allowed to hold positions of power in the public sphere, and women were seen as fragile objects to be protected, not humans with opinions of their own. At many points (particularly in Betteredge’s narration), female characters are blatantly managed by their male counterparts. For example, the interaction illustrated in the above photo is preceded by a “hysterical” outburst from Lady Verinder, blaming Sergeant Cuff for Rosanna’s death. Following this, Betteredge narrates, “The Sergeant was the only one among us who was fit to cope with her… ‘I am no more answerable for this distressing calamity, my lady, than you are,’ he said. ‘If, in half an hour from this, you still insist on my leaving the house, I will accept your ladyship’s dismissal, but not your ladyship’s money.’ It was spoken very respectfully, but very firmly at the same time – and it had its effect on my mistress” (Collins 158). While Lady Verinder was certainly in a position of power in her household, the fact remained that she was a woman, and in the eyes of the men surrounding her thus more prone to things like hysterics. This is evident in the above image: Lady Verinder is sitting, while the two gentlemen are standing over her, demonstrating their capability while she languishes in her voluminous skirts.

This last image follows along the lines drawn between men and women in the Victorian era, and the contrasting standards for magazines in Britain and magazines in America. As opposed to the British publication, which immediately begins another story after the conclusion of this segment of The Moonstone, the American publication breaks up the intellectual articles and stories with humor and pictures. However, even though at first glance this humor appears to be benign, it reinforces negative female stereotypes and introduces the American version of British classism: that of the division between different religious sects. The humor of the day highlights the perceived failings of women in being hysterical, very focused on husband-finding, and overall rather silly. This is a sentiment reflected in Betteredge’s narration in Part Twelve of The Moonstone, when he says “When you are ill-used by one woman, there is great comfort in telling it to another – because, nine times out of ten, the other always takes your side” (Collins 160). Clearly, Betteredge views female loyalty as fickle, and wholly dependent on the whims of the men surrounding them. This paternalistic point of view separates both women from men, and women from each other, exhibiting the insidious belief that there is no common feeling between women in the same way that there is camaraderie between men.

On the surface, the differences between the two publications in which Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone first appeared are negligible. They are a product of the different countries in which they originated; who needs to look beyond that? However, upon closer interrogation, these differences are indicative of larger divides in the Victorian era. The pizzazz of America’s Harper’s Weekly is in direct contrast to the austere publication in All the Year Round, reflecting the forced differentiation between America and Britain during the American Revolution not one hundred years before. Further, the American illustrations reflect the separation between the private societal sphere containing female roles and the public sphere in which men conducted business. Overall, the bindings in which it was presented doesn’t truly have an effect on the novel; it’s the same words, the same story, even on opposite sides of the Atlantic Ocean. Yet by the end, the impression it leaves on the reader will be molded by the formatting of the story. Those who read All the Year Round will subconsciously receive a message of British superiority, and those who read Harper’s Weekly the underlying implication of female inferiority. Modern readers who read The Moonstone in its novel form will miss the historical peculiarity of the publication’s outside context; however, there is something to be said for reading a novel uninterrupted.

WORKS CITED

Bonner, John, et al., editors. Harper’s Weekly. [Harper’s Magazine Co., etc.], 1857.

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone. Oxford University Press, 1999.

Dickens, Charles. "Amongst Russian Peasantry." All the Year Round, vol. 19, no. 465, 1868, pp.

343-346. ProQuest, https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.

proquest.com%2Fhistorical-periodicals%2Famongst-russian-peasantry%2

Fdocview%2F7951469%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D9838.

Free, Melissa. “‘Dirty Linen’: Legacies of Empire in Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone.” Texas

Studies in Literature and Language, vol. 48, no. 4, 2006, pp. 340–371. Winter.