Part 14 - Owen Bromley

As Ian Duncan Notes, the peculiarity of Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone is that “the loss of the diamond soon becomes secondary to a more urgent concern with loss of character” (306). This is no doubt in accordance with Said's famous notion that “empire appears nowhere because it is everywhere, the invisible cause of a domestic scenery of realist effects, informing the text as ‘a structure of attitude and reference’” (Duncan 296). In The Moonstone these references stretch from Robinson Crusoe to disease and disfigurement. Such discursivity is reflected too in the cast of narrators who combine to create what is on one level a unified narrative and on another level a work in conflict with itself. This is why, for Duncan, The Moonstone “resists an ideologically closed justification of empire by grimly but far from mournfully depicting India as a powerful alien origin that constitutes the limit or end of English national historical identity” (319). This limit of identity Duncan speaks of —what he calls “imperialist panic”— is a fear that “in taking away their [the colonized] history, so to speak, our [the colonizers] history is no longer our own” (319). In section fourteen Miss Clack takes over the narrative to describe the assault and brief internment of Mr. Ablewhite and Mr. Luker by a group of men, one of them with an arm “of a tawny-brown colour;” the presence of the Indian Other on British soil (Collins 191). On the rest of this page I will analyze how the news articles and advertisements from Harper’s Weekly contrast with the fiction from All the Year Round that surrounds the fourteenth installment of Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone, in regards to how the differing depictions of Russian imperialism undermine the presence of the Other. Further, I will analyze how this negation seeks to palliate imperialist panic in Britain and affirm American imperialism through propagating a veil of resistance, ultimately encouraging inverse readings of Miss Clack, that both end up promoting imperial ambition.

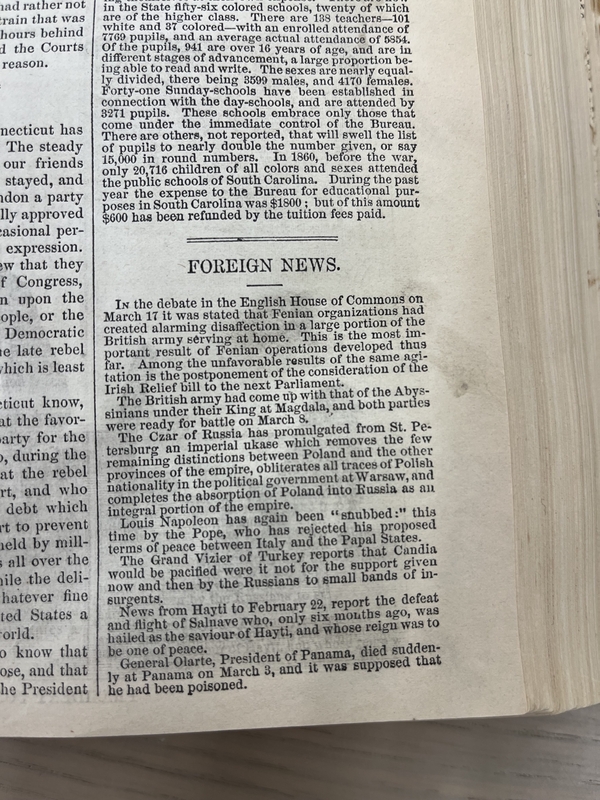

Foreign News in Harper's Weekly

The evocation of imperial repression in this artifact allows the American reader to identify with the repressed, contributing to a reading of section 14 that aligns with resistance, but ignores historical and cultural difference, undermining the true horrors of imperialism that America takes equal part in. In this artifact from Harper’s Weekly, various worldwide events happening outside America are described. There is one event that is implicitly referenced in All the Year Round as well, and looks at the theme of imperialism so prevalent in The Moonstone from a different angle. This event is the integration of Polish territories into the Russian Empire. The blurb here highlights that this absorption “obliterates all traces of Polish nationality in the political government at Warsaw” (“Foreign News”). The American position during this time is quite interesting as being a nation founded by British ambition and imperial culture, but defined by its defiance of its origin of imperialism, which, of course, it still hypocritically projects as it dominates over the indigenous populations. The two sides of imperialism that the American position assumes are both ends of what Tamar Heller has identified at the conclusion of The Moonstone, the promise of “‘a repetition of the historical cycle in which repression is followed by resistance’” (Duncan 303). Building off this point, Duncan maintains that this “cyclical recurrence marks an imaginary domain that exceeds mere history or at least the Western linear history that guarantees the narrative of imperial progress” (303). I would suggest that due to its historical positioning, the American assumption of both resistance and repression, ends up furthering imperial progress. Its resistance to British imperialism undermines its repressive action towards the indigenous, as it continues forth, exerting imperial power exactly as the British, only with the veil of resistance. Given this veil, the paratext’s mention of a marginalized European group becoming subsumed into empire might inspire the reader to see the Indian’s attempted reclamation of the diamond in The Moonstone as justified; while at the same time ignoring social, historical and cultural difference between the American and Indian positions, missing how imperialism acts to exert dominion over the foreign Other.

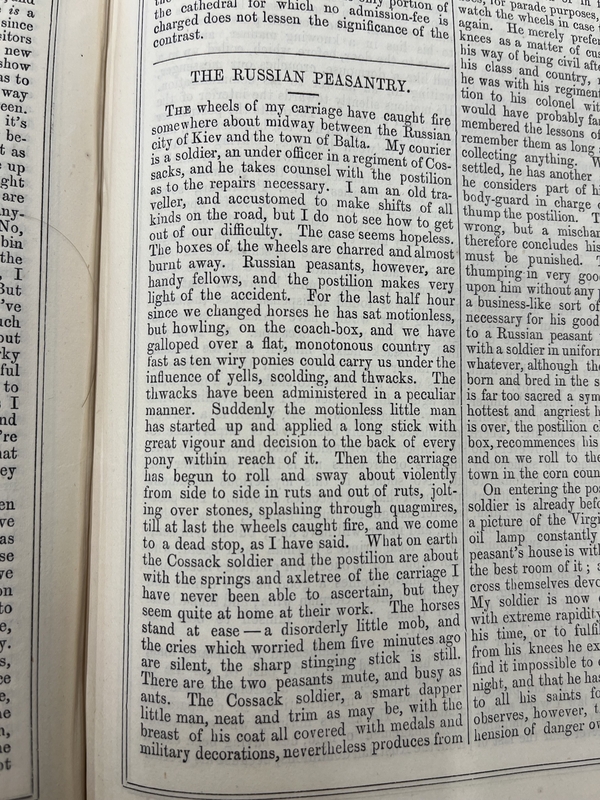

The Russian Peasantry (1) in All the Year Round

Through its avoidance to address the repressed Other, this artifact might serve to quell the reader of any imperialist panic generated by Miss Clack in section fourteen of The Moonstone. Though never once directly mentioning the Russian ukase that integrates Polish regions into the Russian Empire, this short story is no doubt addressing, and indeed commenting, on this issue. In the very first sentence of this four page story the protagonist is described as going between the Russian cities of Kiev and Balta. Kiev and Balta are presently part of the nation of Ukraine, however, for a long time leading up to the Russian annexation, they were a part of the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth. The narrative presented has in one line enacted what was described in Harper’s Weekly, the obliteration of Polish [as well as Ukrainian] nationality (“Foreign News”). This suppression is not that of the direct imperialist nation however; here, it is not Russia that enacts the suppression of the Polish/Ukrainian identity, it is the British publication. This decision to describe Kiev, Balta, and the local peasantry, as Russian is done in the consciousness of British imperialism; to quell what Duncan has observed to be growing imperialist panic caused by the Indian mutiny of 1857 and further insurgencies from Jamaica to New Zealand (305). The anti-imperialist sentiments from The Moonstone come in two forms, the true conditions of alienation and mistreatment of the Other —perhaps best displayed by Ezra Jennings— and this notion of imperialist panic —essentially, the fear of Otherness. Duncan (307), as well as Al-Neyadi (185), both note Betteredge’s embodiment of the fear of Otherness displayed by the quote: “‘here was our quiet English house suddenly invaded by a devilish Indian Diamond.’” But Miss Clack certainly possesses the very same fear, she writes “how soon may our own evil passions prove to be Oriental noblemen who pounce on us unawares!” (Collins 192). In the context of this section, this paratext’s elimination of the Other’s identity in place of the empire’s might serve to comfort the British reader excited by Miss Clack, and as such as such dissuade the reader from anti-imperialist notions that arise from their fear of the Other, embodied through racist sentiment.

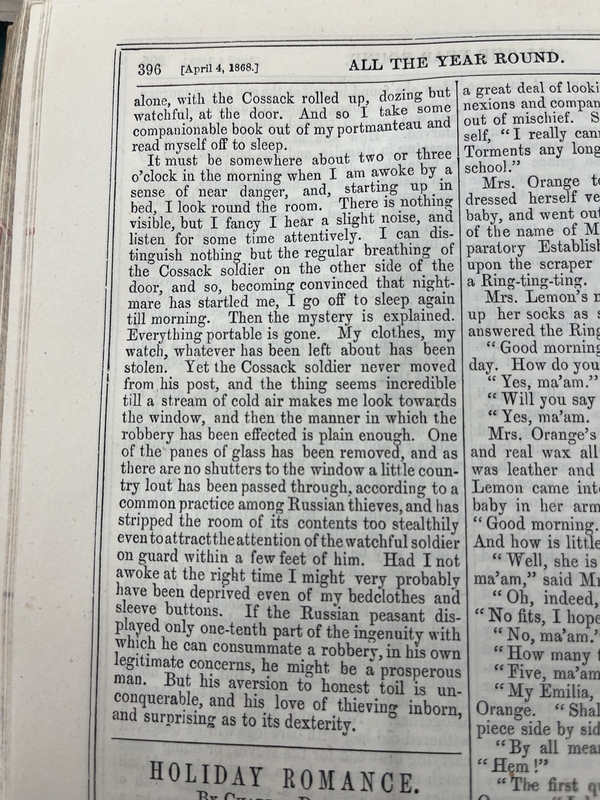

The Russian Peasantry (2) in All the Year Round

This artifact might influence its readers not to see Miss Clack’s character as a satire, by replicating the same move she performs, where resistance to imperialism is explained as natural and barbaric tendencies. The artifact presents the ending of “The Russian Peasantry,” wherein the British traveler is awoken in the night to find that someone has snuck into his room and robbed him of his possessions. The traveler declares the Russian peasant to have an “inborn” love of thieving, and that if they “displayed only one-tenth part of the ingenuity with which he can consummate a robbery, in his own legitimate concerns, he might be a prosperous man” (“The Russian Peasantry (2)”). What a tremendous coincidence that only a few pages after section fourteen of The Moonstone there is another tale of a British person being robbed by someone Other to them! Of course there are many differences between these stories. Crucially, in “The Russian Peasantry” the narrative is told from only one perspective, as opposed to the multiple narrators in The Moonstone. While Duncan sees these multiple perspectives as rendering the imperialist position in a suspended state (300), Al-Neyadi sees it as a discursive manner of locating the ultimate truth that is looked over in much of the novel, the diamond’s rightful owner (188). The singular position of “The Russian Peasantry,” then, in contrast to The Moonstone, sees its final theft as without good reason —the mere nature of the Russian peasant— and ignores what Ilana Blumberg might consider the debt caused by the Russian seizure of Ukrainian/Polish land/culture (Blumberg 169). This piece of paratext might influence the British reader into performing the exact “Christian psychomania” that Miss Clack is clearly meant to satirize, by obfuscating the cause of the theft as pure heretical instinct, instead of the recovering of a cultural debt (Duncan 308). Such a position seeks to obliterate the Other’s culture through the naive replacement of culture with instinct, thereby eliminating the possibility of the empire’s own culture being impacted by the Other’s and resolving any imperial panic.

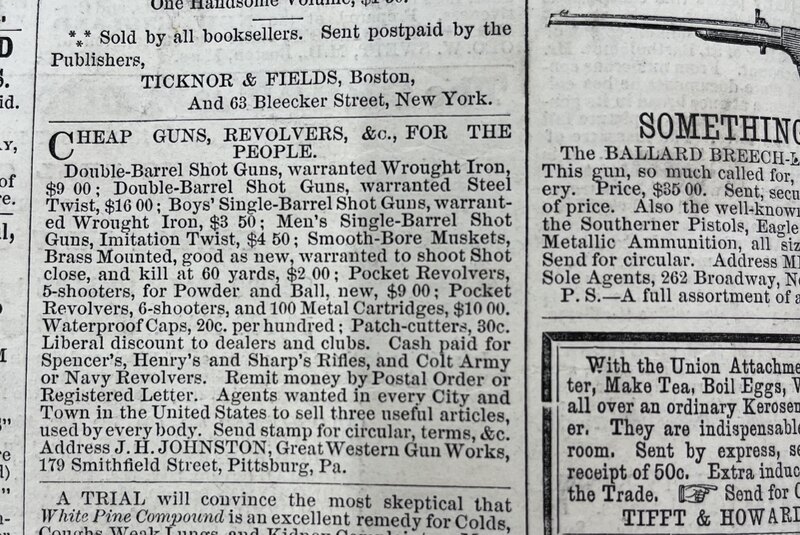

Cheap Guns for the People in Harper's Weekly

This ad provokes its readers to imagine what might happen if Mr. Luker or Mr. Godfrey were able to defend themselves from their Indian abductors, inspiring the foundational American belief in gun ownership as a resistance to imperialism while at the same time imagining the continual repression of the Other, once again contributing to a reading of The Moonstone that misses what is integral about the Indian reclamation of the diamond. This advertisement centered in the image seems fairly typical, it lists many kinds of guns which the company sells and their respective prices. The most notable thing about it is its attention to the national universal. Both in the title, “for the people” and in the body of the ad, “three useful articles, used by everybody” the notion that these guns are for everybody is present (“Cheap Guns For The People”). In addition to its rhetorical function, this idea is heavily inscribed, culturally, and literally —in the form of the second amendment— into the American identity as a resistance to imperialism. The idea that “we all bear arms so that nobody will strip us of our rights.” This idea too is imposed at the personal level; a gun as an article of self defence. It is here we find the overlap with section fourteen of The Moonstone. The paratext suggests to the American reader that if Mr. Luker or Mr. Godfrey had a gun they would be able to defend themselves against the Indian attack. Again we find a sort of duality of the American position; the gun is a device to protect the American from the imperialist, but it is also a tool to protect them from the retribution of the repressed, represented in Collin's narrative by the reclimation of the diamond. This American paratext which evokes historical American resistence, promotes a sympathetic reading of the ambitions of the Indians in The Moonstone, but by doing so it decontextualizes them by drawing implicit equations to the American resistance of the British, thus, realizing the dream of imperial hegemony —the disapearance of the Other, in the case of The Moonstone, the Indian identity.

Despite their apparent inverse relationships to imperialism, in both the Harper’s Weekly and the All the Year Round publications of section fourteen of The Moonstone the paratext presents a tendency to undermine the presence of the Other. The result of this, in both cases, is to assuage the fear of an invasion of cultural Otherness and its accompanying anti-colonial sentiments; thereby contributing to imperial progress. In the British, this is done by turning the Other into nothing by omission, or by reduction, and diluting the satirization of Miss Clack. In the American, Miss Clack is highly satirized through the reader's assumption of the position of the Other, but this assumption destroys the very notion of difference in the first place. As Duncan and Al-Neyadi have argued, the success of The Moonstone is its various narrators which for Duncan suspends, and for Al-Neyadi discovers, the actual colonial and imperialist truths which are always present but rarely addressed in the Novel. Section fourteen ultimately only displays one part of one of these narratives, and the power of these multiple perspectives, which span the spectrum of Otherness, do work to accomplish a discursive investigation into imperialism and colonialism. But, the effect of the paratext from All the Year Round and Harper's Weekly surrounding this section reflects a bigger desire, and indeed encourages its readers, to avert our eyes from the true substance of the novel and to instead focus on the various romances of the characters.

Work Cited

Al-Neyadi. “Depicting the Orient in Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone.” International Journal of

Applied Linguistics and English Literature, vol. 4, no. 6, 2015, pp. 181-9.

Blumberg, Ilana. “Collins’ ‘Moonstone’: The Victorian Novel as Sacrifice, Theft, Gift, and

Debt.” Studies in the Novel, vol. 37, no. 2, 2005, pp. 162–86.

"Cheap Guns, Revolvers, &c., for the People." Harper's Weekly, 4 April. 1968, p. 224.

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone. Oxford World’s Press, 1999.

Duncan, Ian. “The Moonstone, the Victorian Novel, and Imperialist Panic.” Modern Language

Quarterly (Seattle), vol. 55, no. 3, 1994, pp. 297–319.

"The Russian Peasantry." All the Year Round, Edited by Charles Dickens, April 4, 1868, p.

393-6.

"Foreign News." Harper's Weekly, April 4, 1968, p. 211.