Part 15- Stavroula Papaioannou

The British and American periodicals featuring part 15 of Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone invite varied interpretations, the historical context of its publication framing its reading. Advertised as "richly illustrated," Harper's Weekly contained advertisements and cartoons shaped by the Reconstruction era following the American Civil War (Leighton and Surridge 207). By contrast, All The Year Round was almost entirely devoid of illustration, often embedding poems and short stories alongside its featured serialised novel. Mary Elizabeth Leighton and Lisa Surridge suggest that the illustrations of serialised Victorian novels "do not merely reflect or supplement the text… but profoundly [affect] the narrative's unfolding and meanings" (210). For The Moonstone, the illustrations in the post-bellum context of Harper's Weekly add to the "complexity" of the novel, "creating interpictorial effects of irony, juxtaposition and parallelism" (Leighton and Surridge 211). Extending Leighton and Surridge's argument that illustrations give rise to more intricate interpretations, this exhibit examines how the novel's American audience -- exposed to paratextual visuals -- may have negotiated Miss Clack's identity differently than its British counterpart. While the moralistic texts in All The Year Round sharpen Collins's satirical depiction of Miss Clack, the illustrations and comics in Harper's Weekly offer an alternative reading. I argue that Harper's Weekly imbues Miss Clack with a complexity absent in the British periodical, framing her as a product of an oppressive system that she must navigate, often in contradictory ways.

This illustration, titled "She stopped—Ran Across the Room—and Fell on Her Knees at Her Mother's Feet," follows Rachel Verinder's hearing of the rumor of Godfrey Ablewhite's involvement with the moonstone. In this depiction, Rachel and Mrs. Verinder occupy the center of the image; Rachel's look of strife, along with her physical closeness to her mother, paints a picture of filial devotion. By contrast, Miss Clack is relegated to the background, positioned as an outsider looking in on the scene rather than an active participant. This physical disjunction reinforces Collins's satirical depiction of her in the text: while Miss Clack accuses Rachel of being "too vehement to notice her mother's condition," her inability to empathize with Rachel's distress underscores the hypocrisy of her judgments (Collins 203). Miss Clack criticizes Rachel’s behaviour under the guise of moral concern, yet her detachment and lack of compassion reveal a stark contradiction between the values she claims to uphold and her actual conduct. Her role as a passive observer, further emphasized by her turned head and disinterest in the scene’s emotional intensity, mirrors her narrative tendency to cast judgment from a distance while failing to embody the Christian virtues she preaches.

hhhhBeyond echoing Leighton and Surridge's contention that The Moonstone's illustrations emphasize its "mockery of evangelicalism," Miss Clack's depiction also positions her as a figure on the margins (214). While Godfrey also plays the spectator role here, his looming presence over Rachel and Mrs. Verinder signals his more significant involvement in the narrative. Miss Clack, by contrast, is visually diminished; note the light etchings of her dress blending into the walls, another marker of her physical and emotional exclusion. This marginalisation is compounded by her lower social class, which further distances her from the Verinders and emphasises her outsider status. Rather than being purely a source of ridicule, the illustration frames her as victimized by the same Victorian norms she claims to enforce. Miss Clack is a manifestation of societal expectations that demand women embody perfect moral and religious ideals while simultaneously ostracizing those who enforce those ideals too zealously. In this way, Miss Clack's hypocrisy becomes less a personal flaw and more a symptom of the rigid norms she is trying—and failing—to navigate.

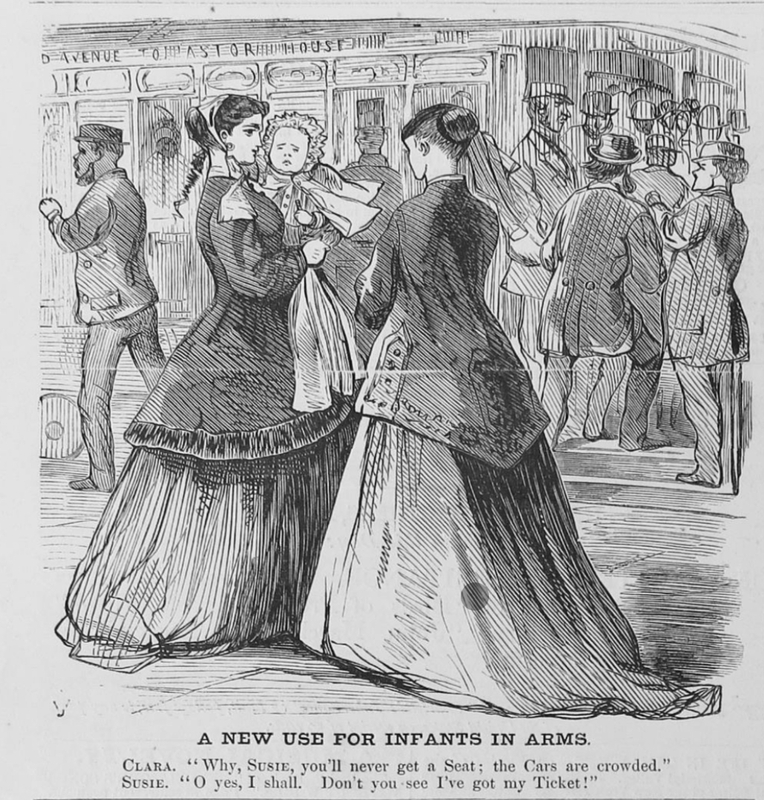

Building on the critique of Victorian womanhood seen in The Moonstone illustration, “A New Use For Infants in Arms” satirises the negotiation of womanhood under rigid gender norms, further complicating Miss Clack's characterisation. In conversation with Clara, Susie marks her baby as her “ticket,” ensuring her seat. Susie’s assertion subverts the traditional, self-sacrificing role of a mother, humorously reframing her relationship to her child as transactional. The blank expression of the baby reinforces this statement, positioning the child as a mere prop for her use. Susie’s manipulation of gender expectations highlights the performative nature of these roles, exposing how they often serve societal demands rather than authentic expressions of femininity. Observe also the public setting of the illustration: Susie and Clara’s central positioning in a traditionally male-dominated space challenges the Victorian association of womanhood with domesticity. The wordplay of “infants in arms” – echoing “brothers in arms” – reinforce their resourcefulness and navigation of gendered constraints for practical benefit. This satirical framing directly parallels Miss Clack’s performative morality, linking the cartoon’s critique of maternal selflessness to her performative religious piety.

Like Susie, Miss Clack manipulates Victorian ideals—particularly those tied to morality and femininity—for her own purposes. For instance, Miss Clack critiques Rachel’s behaviour as improper while admitting that she is “hemmed in… between Mr. Franklin Blake’s cheque on one side and [her] own sacred regard for truth on the other” (Collins 198). Just as Susie pragmatically uses her child to secure a seat, Miss Clack navigates societal expectations of Christian virtue to maintain her moral standing. The juxtaposition of “Mr. Franklin Blake’s cheque” with her professed “sacred regard for truth” underscores the performative nature of Miss Clack's moral posturing. The cartoon also adds complexity to the phrase “hemmed in,” highlighting her entrapment within the oppressive Victorian system. While Miss Clack's tone implies a certain moral authority, this authority is undermined by her financial dependence and performative piety. In this way, Susie’s performance of Victorian norms reveals the ways Miss Clack both upholds and is constrained by societal expectations. The cartoon shifts her characterization from that of a mere figure of religious zeal to an individual navigating the impossibility of Victorian ideals, reinforcing her complex characterisation while deepening the critique of these rigid societal norms.

While the illustrations and comics in Harper's Weekly complicate Miss Clack's characterization, "The Devil Outwitted" – appearing in All The Year Round – sharpens her hypocricy through satirical parallels. Subverting the "Angel of the House," the "Devil's wife" serves as a hyperbolic figure of condemnation, embodying Victorian anxieties surrounding women who deviate from their prescribed roles. The narrative emphasises the inherent "wickedness" of the wife, which far exceeds that of her devil husband. Her deviance from the traditional housewife, "scolding and quarrelling without rhyme or reason," invokes instability in the home, rendering it a place of torment. The Devil's assertion that the "late infernal residence was paradise" when compared to "a witch of a woman for a wedded wife" further signals the gendered condemnation at play. Here, the wife's defiance of expectation is so transgressive that hell becomes "paradise." This hyperbolised description of the Devil's wife mirrors Miss Clack's descriptions of Rachel, framing her as the "Devil of the House." Observing her interaction with Mr. Godfrey, Miss Clack describes Rachel as "approach[ing] [him] at the most unladylike rate of speed, with her hair shockingly untidy, and her face, what [she] should call, becomingly flushed" (Collins 197). Rachel's "unladylike speed," "shockingly untidy hair," and "flushed" face echo the "scolding and quarrelling" of the Devil's wife. Just as the wife's active stance signals her "vileness," Rachel's decisiveness marks her similarly "unladylike," stripping her of femininity. In this way, both act as markers of defiance against Victorian ideals of femininity, challenging the gendered norms of the domestic sphere.The parallels in narrative voice between "The Devil Outwitted" and Miss Clack reduce her to a figure of ridicule, villainising Rachel's trangression from her gendered subordination.

Featured in All The Year Round, “Freaks in Flanders” reinforces Miss Clack’s hypocrisy through its critique of performative religiosity. In the speaker’s description of religion in Flanders, the listing of excesses, including “splendid processions, glittering banners, [and] precious gems,” underscores the ostentatious display of piety, valuing appearances over genuine devotion. This decorative imagery mirrors the excess it critiques, emphasizing the hollowness of the religious practices. The text overtly condemns the performative nature of this piety, asserting that “prayer [is] measured by quantity and duration instead of fervour and devotion.” By contrasting external, quantifiable displays of faith with the more interior processes of “fervour and devotion,” the speaker critiques the prioritization of visibility over sincerity. This critique aligns with Miss Clack, whose self-righteousness similarly exposes her own performative behaviour. Miss Clack’s hypocrisy becomes particularly evident in her admonishment of Rachel Verinder, asserting that "true greatness and true courage are ever modest” (Collins 198). Here, Miss Clack equates Rachel’s assertiveness with a lack of modesty, aligning herself with the very performativity critiqued in "Freaks in Flanders." While she preaches “true greatness” and “true courage,” her judgment of Rachel is rooted in societal expectations of subdued femininity rather than any true moral principle. Much like the performative religion in Flanders, Miss Clack’s outward displays of piety privilege visibility and conformity over true sincerity. The overt critique of Victorian religious practices in “Freaks in Flanders” plays up Miss Clack’s own moral fallibility, characterising her through her contradictions. This contrasts sharply with Harper's Weekly, which offers a more layered portrayal of Miss Clack.

While Harper’s Weekly and All The Year Round negotiate Miss Clack’s characterization differently, they both deepen The Moonstone’s critique of the underlying hypocrisy and power structures in Victorian society. Part 15 of the novel – positioned after the theft of the Moonstone but before the mystery's resolution – particularly exposes the inherent contradictions in Miss Clack’s narrative. Miss Clack’s unreliability reflects the broader theme of narrative instability in the novel, which Leighton and Surridge describe as requiring the reader to navigate “intersecting narratives” and a “frequently shifted point of view” (210). Miss Clack's narrative voice, riddled with self-serving moral judgments and overt biases, exemplifies these shifting perspectives, as her account distorts events to align with her moral agenda. This manipulation mirrors the broader structure of the novel, where no single perspective offers an authoritative truth. Instead, readers must critically engage with these “intersecting narratives” to discern reality. By amplifying Miss Clack’s unreliability, All The Year Round reinforces her role as a satirical figure, while Harper’s Weekly complicates her character, positioning her hypocrisy within the constraints of Victorian norms. Together, these treatments encourage a critical reading of Miss Clack’s account, situating her contradictions within the novel’s larger exploration of truth, morality, and societal pressures.

Works Cited

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone. Oxford University Press, 2019. Print.

Leighton, Mary Elizabeth and Lisa Surridge. "The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper's Weekly." Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 42 no. 3, 2009, p. 207-243. Project MUSE, https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/vpr.0.0083

"A New Use For Infants in Arms" Harper's Weekly, 11 April 1868: p. 240. https://web-p-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/ehost/archiveviewer/archive?vid=3&sid=74fb31cf-59d1-41d7-9bdd-4b6abc191623%40redis&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#kw=true&acc=false&lpId=divl031&ppId=divp0016&twPV=&xOff=0&yOff=0&zm=fit&fs=&rot=0&docMapOpen=true&pageMapOpen=true&AN=67540877&db=h9m

"Freaks in Flanders" All The Year Round. 11 April 1868, p. 418, Dickens Journals Online.

https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-periodicals%2Ffreaks-flanders%2Fdocview%2F8058127%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D9838

“She stopped— Ran Across the Room — and Fell on Her Knees at Her Mother’s Feet” Harper’s Weekly, vol. 12, no. 589, Apr. 1868, pp. 229. https://web-p-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/ehost/archiveviewer/archive?vid=4&sid=74fb31cf-59d1-41d7-9bdd-4b6abc191623%40redis&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#kw=true&acc=false&lpId=divl012&ppId=divp0005&twPV=&xOff=0&yOff=0&zm=fit&fs=&rot=0&docMapOpen=true&pageMapOpen=true&AN=67540863&db=h9m

"The Devil Outwitted" All The Year Round. 11 April 1868, p. 416-417, Dickens Journals Online. https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-periodicals%2Fdevil-outwitted%2Fdocview%2F7894330%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D9838