Part 16 - Natalee Munoz

In the third chapter of The Moonstone’s second narrative, Miss Clack's position as a woman is established through her interactions with Lady Verinder and Mr. Bruff. This exploration of women within the novel highlights “women's rising awareness of the precariousness of their situation in the patriarchal society of the 1800s” (Cruea 1). As a character Miss Clack embodies the themes Wilkie Collins critiques as she reflects a woman who is subjected to both gender inequality rooted in the patriarchal ideals and class-based inequality among women. Her position as an unwed woman without any status and financial independence reflects the intersection of both gender inequality and class disparity. The use of images within the American publication Harper’s Weekly presents a caricature of Miss Clack that reflects the anxieties present in 19th century America as the theories that sparked the women's rights movement challenged traditional ideals. This compares to the serious portrayal within the British publication, Dickens All the Year Round which brings forth a nuanced discussion on Miss Clack’s role as a woman as the reader must engage solely in her narrative voice. Looking at these ideas concerning Miss Clack shapes the way women are understood within the novel as their lack of agency comes directly from the pressures placed on them by society. These observations in the periodicals highlight how patriarchal notions and class-based inequalities shape female identity and positionality, demonstrating that the portrayal of Miss Clack’s character obscures her role as a critique of the societal forces at play in Victorian Britain and post-Civil War America as they influence how she is perceived.

This instalment of The Moonstone in Harper's Weekly opens with an illustration of Miss Clack. This image highlights the strange features of her character, which showcases a caricature-like portrayal. Some of these features that stick out most are her frail appearance and sunken cheeks giving her a wicked, almost sinister look. This sickly appearance contrasts the beauty standard of the period, which had the ideals of feminine beauty being associated with rounded healthy features. This contrasts how Miss Clack fails to fulfil this standard of beauty because of her position as a lower-class woman, reflecting how women in this class were represented in ways that emphasise their weakness and poverty. These notions showcase the ideologies that women in lower classes who do not embody the standards of feminine beauty should not be treated with the same level of respect as a higher-class woman like Lady Verinder. Her depiction also reflects the status of America within the period, during the emergence of feminist ideologies as it marked the beginning of the women's rights movement. This illustration in this chapter also influences how seriously she is taken in her interactions with Lady Verinder and Mr Bruff. She is represented as this comically frail woman who believes she has some sort of moral authority over everyone else, which is amplified by this image. Within this chapter, Miss Clack continues to mention her religious ideas that have no weight because of the already established notion that she is a comedic unreliable character brought forward by this image. Her appearance impacts how an audience conceptualizes her identity can be related to this chapter as she states, “Oh, what pagan emotions to expect from a Christian Englishwoman anchored firmly on her faith” (Collins 208). The undertones of humor in this line influenced by the illustration, undermine her character and diminish the potential for deeper engagement with her beliefs. The portrayal in Harper's Weekly encourages the reader to dismiss her religious ideologies, reinforcing the idea that women's beliefs are overlooked in comparison to their male counterparts who tend to be respected. The use of the image within Harper’s Weekly represents the villainization of women within the time period on a basis of both gender inequality and class disparity as it constructs a reader's perception of her character without leaving room for discourse.

The third chapter of the second narrative within Dickens All the Year Round focuses on the story through its lack of illustrations. As seen in this image taken from the beginning of chapter three of the second narrative, Miss Clack's account of her interactions is not tainted by the illustrations and thus requires the reader to make up their minds based solely on her narrative voice. The serious tone contrasts the American version that guides the reader's understanding, as it allows room for discourse on the ideologies surrounding women's rights and showcases the ability of the reader to make their own judgements on the subject. This approach suggests a more progressive approach to the changes occurring within the 19th century as it marks the beginning stages of the women's rights movement and the desire for gender equality. It also moves away from the contrast of other female characters through class lenses as it requires a more nuanced exploration that is not brought forth through the use of illustrations. Addressing these topics this way reflects how there are deeper complexities to Drusilla Clack as a character as she is involved in the rising awareness of patriarchal issues as addressed by Cruea’s article. This positionality being brought forward is represented within this section of this chapter as she states, “felt prepared for any duty that could claim me, no matter how painful it might be” (Collins 206). The quote initially appears to reflect the character’s sense of duty and willingness to care for her aunt. However, this willingness highlights the societal expectations placed on lower-class women. This idea of being “prepared for any duty” reflects not only personal choice but the constraints placed on women without the title of privilege by society as they must fulfil the role assigned to them. This approach to the publication of Wilkie Collins’s work shifts the understanding of the author's stance on feminist issues emerging at this time and suggests the use of Miss Clack to embody and critique how these women within Victorian society do not have the right in any form of agency based on both class and gender inequality.

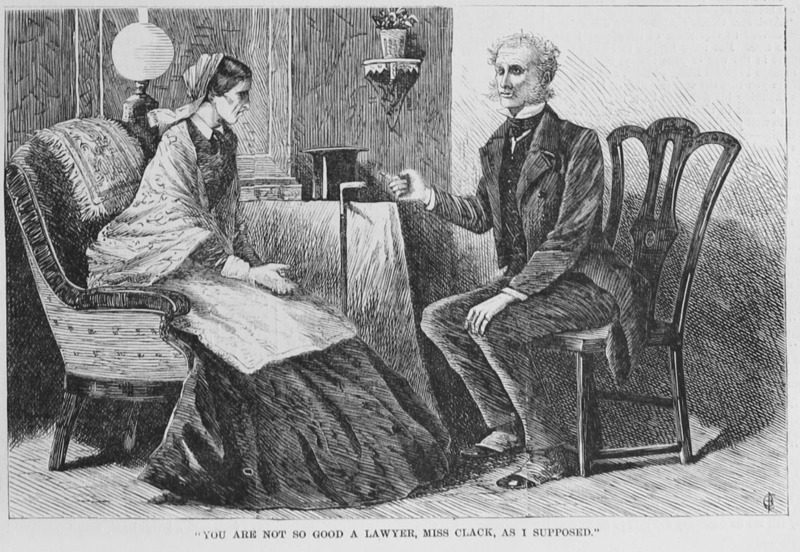

The instalment within Harper's Weekly also includes a second picture that depicts the interaction between Miss Clack and Mr Bruff. The positioning of these characters is unique to this argument as the focal point is not Miss Clack as her face is only half shown. In contrast, Mr Bruff’s full face is shown, which draws the attention to the male with authority over the woman whose narration should be the focal point. The depiction of Mr Bruff is also different from that of Drusilla Clack as his illustration does not have the same humorous portal. These simple features contrast those of Miss Clack as she is represented through a villainous lens with her harsh and sickly features demonstrating the portrayal of women within America and highlighting the anxieties because of questioning traditional patriarchal ideologies arising from the new presence of feminist theories. These notions of a power dynamic because of gender are highlighted as Miss Clack states, “I ought, I know to have set him right before he went any further” (Collins 210), suggesting how as a woman she must refrain from challenging a man. This quote reflects the positioning as gender dynamics during the Victorian era are rooted in patriarchal ideas aligning with the placement of a male focal point in the illustration. Harper’s inclusions bring forth the notion of anti-feminist propaganda, which is emphasised by the image of Miss Clack that is being pushed and shapes her portrayal of her character. This continues within this image as it focuses on the line, “You are not so good a lawyer, Miss Clack” (Collins 213). By focusing on this line this publication emphasises a line within the interaction that is used to belittle her and her approach to the discussion with Mr. Bruff. This line also showcases Mr Bruff's superiority over Miss Clack as she is being told that she is not cut out for the position of power that he is in. These aspects of this illustration demonstrate the patriarchal ideas that influence the construction of a woman's identity and her positionality through the power dynamics represented in interactions between male and female characters.

This instalment ends in the middle of the fourth chapter within the second narrative commenting on the serious nature of its publication and drawing attention to the class inequality of women that is being critiqued. All the Year Round differs from other publications of The Moonstone through its lack of images and focus on text, which is unique and plays on the notion of progressive discourse when it comes to the character Miss Clack. By neglecting illustrations, the audience must rely on the substance within the text, encouraging a deeper understanding of the societal issues that Wilkie Collins critiques, especially at the end of the instalment. The ending of this section is unique as it does not conclude at the end of a chapter, but rather with a cliffhanger that emphasises Miss Clack's positionality, highlighting her lack of agency. Instead of wrapping up the chapter, the story ends with Miss Clack being interrupted as she states she is about to leave to go to Montagu Square but is stopped as the maid has come to get her. This simple act of interruption reflects how Miss Clack as both a woman and lower-class individual must abide by the decisions made for her by the outside world, rather than having the freedom to make her own choices. By ending the instalment during this moment, All the Year Round draws attention to the critique of traditional gender and class ideologies, which were in place at the time of its publishing, demonstrating how the life decisions of women are often out of their hands because of their lack of agency over themselves rooted in gender and class inequality.

Through the comparisons of Harper’s Weekly and Dickens' All the Year Round, it is evident that the discussion of women's rights is embodied through the character of Miss Clack. However, each publication approaches the subject from a distinct perspective. The use of illustrations within Harper’s Weekly reflects the fears seen within 19th-century America as debates over women's rights challenge traditional ideologies. These ideas are represented by Miss Clack's portrayal within the publication through her character representation highlights the publication's use of anti-feminist propaganda that limits a reader's perception of the character. In contrast, All the Year Round supports a more nuanced approach as it relies on the narrator’s sole voice to shape a reader’s judgement when it comes to what the character of Miss Clack embodies. The focus on text represents the figurative exploration of ideals represented within British publications that are more progressive than the American version which tends to push ideologies onto the reader. These differences reveal how political approaches to the topics of gender equality during a period influenced the treatment of feminist ideas within literature. By looking at these two publications it suggests that the character of Miss Clack and her position as a lower-class woman can be represented and understood in different ways based on the political relevance occurring in the place they are published.

Works Cited

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone. Oxford University Press, 2019. Print.

Collins, Wilkie. “The Moonstone: Chapter III.” Harper’s Weekly, v. 12, n. 590, April. 1868, pg. 245-246.

Collins, Wilkie. “The Moonstone: Chapter III.” All the Year Round, v. 19, n. 469, April. 1868, pg. 433-436.

Cruea, S. M. (2005). Changing ideals of womanhood during the nineteenth-century woman movement. ATQ (Kingston, R.I. : 1987), 19(3), 187-.