Part 18 - Cierra Zaghetto

Chapter VI of the Second Narrative in The Moonstone depicts the letters between Miss Clack and Franklin Blake, while Chapter VII shows a chronological jump to Rachel and Godfrey’s engagement and subsequent separation. Reading these chapters in both the American Harper’s Weekly and the British All The Year Round provided me with a vastly different and deeper understanding of Wilkie Collins’ writing. The first thing I noticed between the two publications is that there are significantly more advertisements and vastly more illustrations included in the Harper’s Weekly publication, while there were little to no illustrations in All The Year Round. This indicates a contrast in viewership for the two publications, hinting that Harper’s may want to extend their reach to a larger and more accessible audience, whereas All The Year Round appears to have more strictly intellectual connotations to it. Although Harper’s might be for a wider audience, the publication's subheader, “a journal of civilization,” shows that it is still in agreement with Victorian values and Dickens’ goal to primarily focus on literary content and emphasize societal issues in Victorian Britain through fictional and non-fictional literature alike. I will be using three contextual excerpts from Harper’s Weekly, one being a comical advertisement titled “Wanted,” an opinion piece called “My First Speculation in Oil,” and an illustration from The Moonstone of Roseanna Spearman. From All The Year Round, I have chosen to capture a header from a volume that includes another Wilkie Collins piece called The Woman in White that was published prior to The Moonstone. Taking these images into account with Chapter VI and Chapter VII from our version of The Moonstone, I will show how both publications interpret the societal expectations of women, as well as how they are perceived, and how this is indicated through text and illustrations.

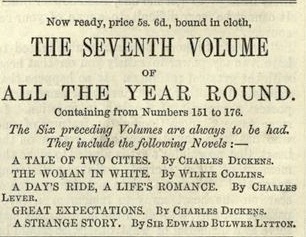

As mentioned, Dickens’ aim for All The Year Round was to explore societal issues that affected Victorians; this is evident through the publishing of Wilkie Collins’ preceding serial novel, The Woman in White. These volumes were published alongside Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities, as well as Great Expectations and a couple of other Dickens works. The Woman in White is a detective novel similar to The Moonstone and entails the story of a teacher who meets a distressed and mysterious woman wearing white whom the teacher helps to seek asylum. The novel has overarching themes about the unequal position of women in society at the time, specifically the unequal position of unmarried women. The story specifically highlights the danger of societal expectations, a perfect piece to be integrated into my other images that, while they do not directly enforce these societal expectations, neither challenge them. The page this header is included in contains only the text from The Woman in White, as well as a simple border around the page. Although the two serials were written five years apart, it shows how Collins is committed to exploring societal concerns. This is compelling for Dickens to include in his publication as it includes social commentary on the state of women’s affairs during the Victorian Period. In Chapter VII, when Rachel is questioned by Miss Clack about her engagement to Godfrey Ablewhite, she exclaims, “I shall never marry Mr Godfrey Ablewhite” (Collins 241). This quote is significant in relation to The Woman in White; it shows Rachel’s willingness to challenge norms in a time where it was disadvantageous for a woman to do so, both economically and socially.

With Collins’ questioning of social norms throughout the novel, it was interesting to see the illustration of Roseanna Spearman that Harper’s Weekly included in the page before the installment of Chapter VI. The image initially captured my attention in my viewing of the periodicals as it struck me as being vastly different than how I conjured Roseanna looking in my mind as I read our edition of The Moonstone. Roseanna, a maid for Lady Verinder, is described as having a deformed shoulder and is often ill. The image we see of Roseanna in Harper’s Weekly is the opposite; she has no physically visible deformity and looks rather put together and polished. Harper’s Weekly is called the “journal of civilization,” so a portrayal of a woman who is a former criminal and is also disabled might not fit the theme of the journal. According to Leighton and Surridge in their article “The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper’s Weekly,” Collins had little input on the illustrations made in the American serial (209), which can indicate a reason for the difference in how Roseanna was perceived. These images are often included to aid readers in connecting to the story in a more emotional way. According to Leighton and Surridge, the illustrations provide the reader with more context to understand the story, which is an already difficult narration structure to follow due to the constant shift in first-person narration amongst its characters (210). This illustration of Roseanna is a further example of how women, and the ideals that society holds them to, are portrayed in these publications. Roseanna should still be, to the viewer, a polished woman and no different than how Rachel would be illustrated.

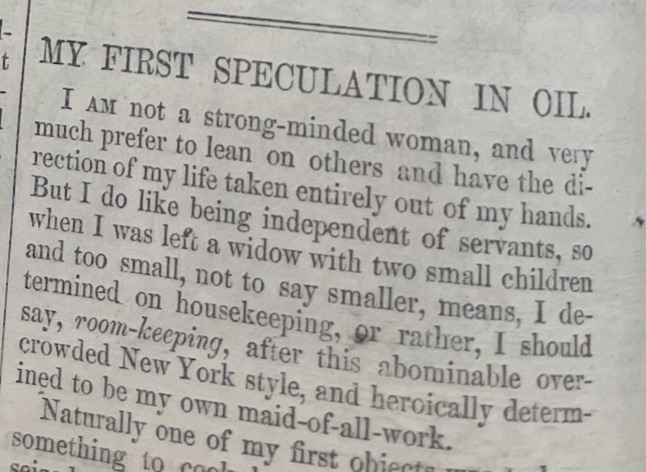

The opinion piece “My First Speculation in Oil” is shown following Chapter VII. My first impression based on the title was that the piece would be about the advancements in the oil industry, given that the 1860s was a time of prosperity in America for such. The first excerpt of the piece indicates differently; it instead entails the wishes of a woman who was recently widowed to be able to take care of her children and her house. In her article “Changing Ideals of Womanhood during the Nineteenth Century Woman Movement,” Cruea claims that the ideal of woman valuing motherhood as “the most fulfilling and essential of all women’s duties” (Cruea 188) is pertinent, as we see in this excerpt. It also indirectly comments on the hierarchy and where women see themselves as placing on it during this time. It seems that widows are higher than servants, even though they are independent of a man. It mentions the city of New York and corrects herself from saying “housekeeping” to “room-keeping.” I wonder if this is a commentary on the city at the time, following the civil war, as the city was in a kind of urban renaissance. This piece can also be read as resistant to modernity and innovation. The opening line, “I am not a strong minded woman, and very much prefer to lean on others and have the direction of my life taken entirely out of my hands,” reflects how others want women to be seen at the time. The placement of this piece is intentional; since we see an act of independence from Rachel at the end of Chapter VII, this could be an attempt to refocus the reader on the norm. Although it is written in first-person, we do not know if a woman wrote this article, as it could be a man posing as one for the sake of influencing the masses, either for them to pass on these ideals to their wives or for women to read themselves.

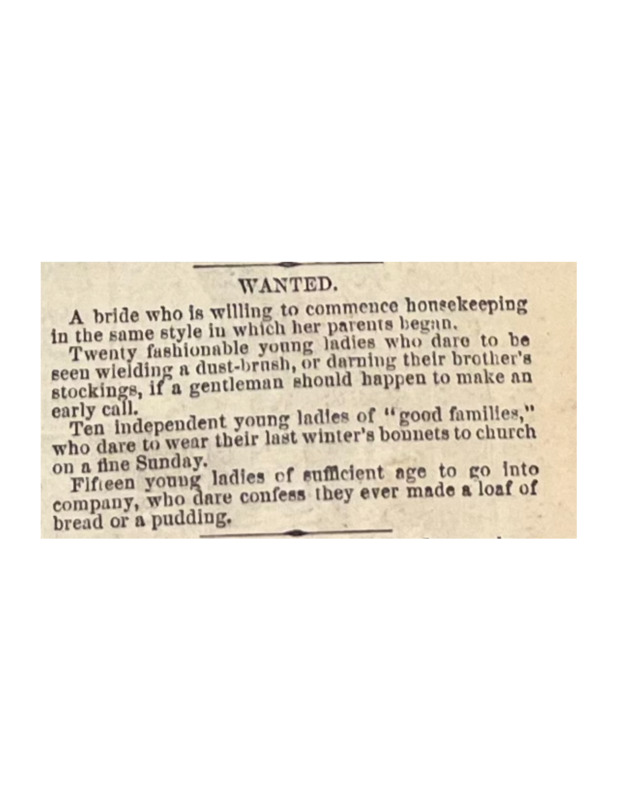

A distinct difference between Harper’s Weekly and All The Year Round is the inclusion of comedic cartoons and sections. “Wanted” is a comical ‘advertisement’ that was found under the “Weekly Humour” section of Harper’s Weekly following the comic section. In the same section, there is a comic that features Christmas being portrayed as a ‘battle,’ with the only portraits of women being shown in the kitchen, or a woman of colour as a maid. The last part of the advertisement appears to be poking fun at the conventional nature of women at the time, like using phrases such as women who “dare to wear last winter’s bonnets to church,” appearing to mock women who frequently buy new clothes. It is also interesting to point out the amount of women they are inquiring for, the quantities being “twenty fashionable,” “ten independent,” and “fifteen young.” These descriptors show what are seen as important values for women in America during the 1860s to hold. It is important to note that women were often held to a stronger protocol, as well as adhered to a more rigid class structure in Britain than they were in America. Gender is an important exploration in The Moonstone and often aims to expose the rigid gender roles that characters feel they need to be confined to. As Betteredge often repeats that women are inferior to men and instead need to be protected by the men, characters like Miss Clack are seen to push these boundaries. Miss Clack is portrayed in Chapter VI to be a woman who does not uphold these standards that Betteredge and society hold her to. Her character serves to satirize Victorian womanhood and how women are often portrayed as they are in my other contextual images. In one of the letters in Chapter VI, it is described that “Miss Clack feels it an act of Christian duty to inform Mr Franklin Blake that his last letter—evidently intended to offend him—has not succeeded” (Collins 233). According to Cruea’s article, throughout the nineteenth century the idea of a ‘True Woman’ began to gain popularity; this idea entailed that this type of woman was “designated as the symbolic keeper of morality and decency within the home, being regarded as innately superior to men when it came to virtue” (Cruea 188). Miss Clack is actively resisting the idea of a ‘True Woman’ as the reader often questions her virtue and morality, not only as a Christian but as a woman.

In conclusion, Chapters VI and VII of The Moonstone offer two instances of women challenging the societal norms they encounter. Comparing the two periodicals The Moonstone was published in allows for readers to view the similarities and subtle differences between both cultures. While Wilkie Collins is consistent in his exploration of women’s social positions throughout the serials The Moonstone and The Woman in White, there is still a vast amount of material published to reinforce these social structures, such as in “My First Speculation in Oil” and “Wanted.” Even the usage of a character such as Roseanna, who is supposed to offer representation for those who do not fit into these standards, is changed in her illustrations to be deemed more appealing to the readers of the periodical. Although each publication takes place on opposite sides of the Atlantic, both aim to display the tension between social expectations and individual agency of women that is prevalent in the Victorian Era.

Works Cited

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone. Oxford University Press, 2019. Print.

"The Seventh Volume." All The Year Round. 11 October, 1862, p. 120, Dickens Journals Online,

https://www.djo.org.uk/all-the-year-round/volume-viii/page-120.html

"THERE SHE WAS, ALL ALONE, LOOKING OUT ON THE QUICKSAND AND THE SEA."

Harper’s Weekly: A Journal of Civilization, 11 January 1868: p. 21, print.

Leighton, Mary Elizabeth and Surridge, Lisa. "The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the

Illustrated Serial in Harper's Weekly." Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 42 no. 3, 2009, p. 207-243. Project MUSE, https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/vpr.0.0083

"My First Speculation in Oil." Harper’s Weekly: A Journal of Civilization, 18 January 1868: p.

38, print.

Cruea, Susan M. “Changing Ideals of Womanhood during the Nineteenth Century Woman

Movement.” University Writing Program Faculty Publications, 2005, https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=gsw_pub

"Wanted." Harper’s Weekly: A Journal of Civilization, 11 January 1868: p. 27, print.