Part 3 - Bethany Pauls

The plot of Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone centres on the titular diamond, taken by Colonel Herncastle from India to England. British imperialism in India therefore sets the context for events that play out in grand English houses, impacting the relations of civilian characters and culminating in the murder of a once-admired man. The degree to which Wilkie intends a sweeping critique of imperialism is debatable, but his indictment of colonial greed is clear. Would readers have equated Colonel’s violent theft of the diamond, something not only valuable but sacred, with Britain’s plunder of cultural heritage throughout their empire? In part three of The Moonstone, the Colonel reappears, an isolated man on the verge of death, and bequeaths the diamond to Rachel. While the text of the British All the Year Round installment and the American Harper’s Weekly installment match, the surrounding content evinces distinct perceptions of the British Empire. By exploring connections between The Moonstone and the articles, illustrations and stories in the January 18, 1868 editions of All the Year Round and Harper’s Weekly, we can surmise that American readers may have been better tuned to the novel’s anti-imperialist elements than British readers.

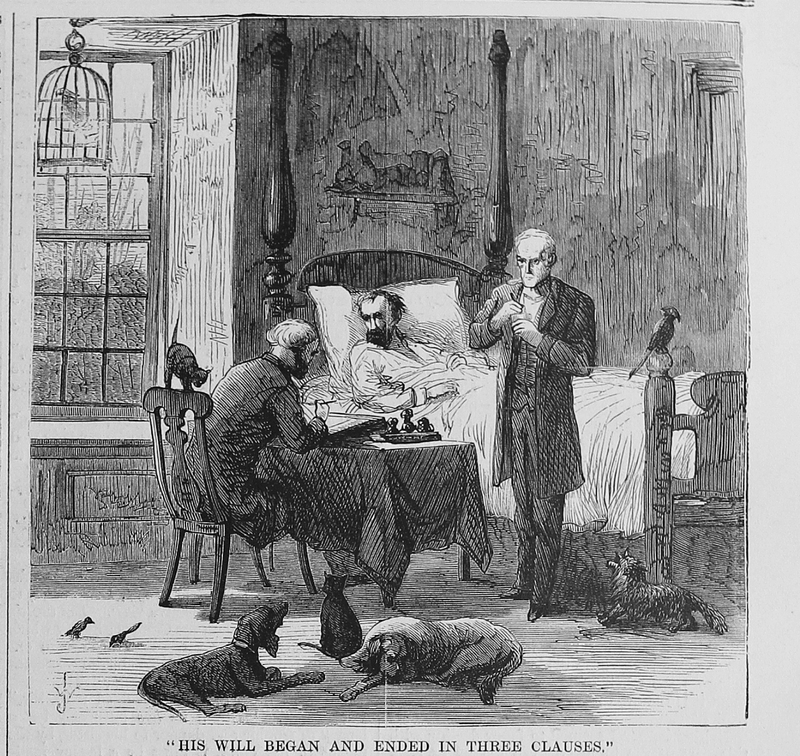

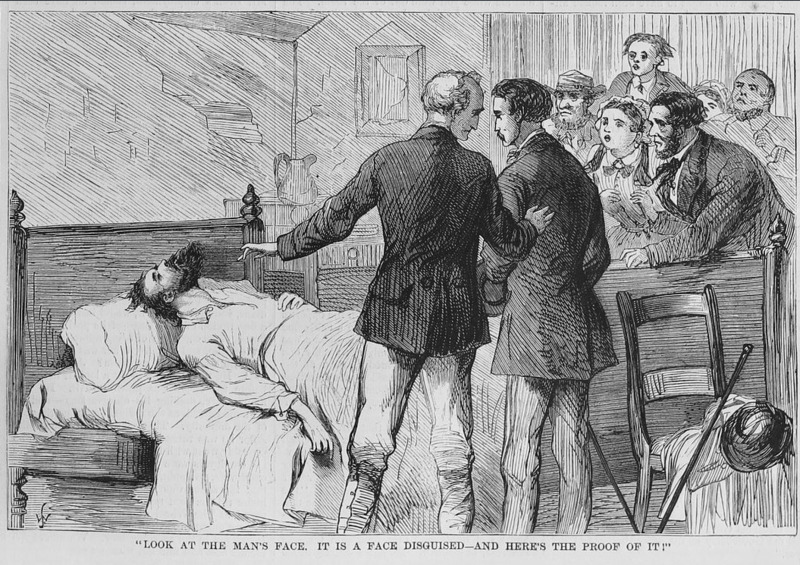

As scolars Mary Elizabeth Leighton and Lisa Surridge note, Colonel Herncastle’s depiction in this Harper’s Weekly illustration is similar to the murdered Godfrey Ablewhite in part 31, visually connected by “their lonely deathbeds, their darkly bearded faces highlighted against white sheets and their solitary bodies surrounded by figures of officialdom” (217). This visual parallelism ties together the two deaths and the novel’s two villains, whose greed turned them to figures of “imperial violence” (Leighton and Surridge 230). The illustrators use Ablewhite’s disguise to make him appear not like the Indians he tries to imitate, but like the dying Colonel. Furthermore, the inclusion of animals in the illustration underscores the text’s statement that he had only “dogs, cats, and birds to keep him company; but no human being near him” (Collins 37). While Herncastle’s cunning prevented his murder, death found him friendless, nonetheless. The illustrations of The Moonstone therefore emphasize the Colonel’s wrongs and his resulting isolation, forming “an intrinsic part of the novel’s interrogation of…the British imperialist project” for an American audience (Leighton and Surridge 217).

The Colonel claims that the diamond came to him through the “the fortune of war” in the accompanying text, as though it were given to him by some goddess (Collins 37). This is an interesting turn of phrase, reflective of the British attitude toward plunder of cultural items. As Historian Lucia Patrizio Gunning and researcher Debbie Challis note, the British carried out an “inglorious tradition of plundering and destroying cultural heritage in warfare” (571). They acquired treasures like the Rosetta Stone for the British Museum through “military plunder” (555).While Herncastle garnered an unfavorable reputation due to his violence and greed, expelling him from his family circle, it can be argued that he only replicated a pattern often repeated on a national scale. Collins’ depiction of “the wicked Colonel”, as Betteredge terms him, may therefore have read more noticeably as a critique of British imperialism and cultural theft in America (Collins 37).

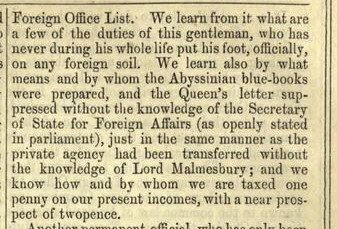

Turning to the British publication All the Year Round, we find references to a historical event that shows similarities to events in The Moonstone. In “Another Species of Official Midge”, the author, who is likely Charles Dickens, critiques the British Foreign Office, noting the poor selection and preparation of many “servants of the British crown abroad” (132-33). The section above cites the Foreign Office List. Nearly lost in a vast list describing the purported duties of the Political Under Secretary is a mention of “the Abyssinian garbled blue-books”, perhaps an insertion by Dickens. These blue books are referenced throughout the article, hinting at British actions in Africa that strikingly resemble Hearncastle’s theft of the Moonstone. These books were prepared in advance of the 1867-1868 expedition to Maqdala in present-day Ethiopia, an event that neatly coincides with the serialization of The Moonstone. This expedition was a punitive strike against Emperor Tewodros II of Abyssinia, in response to him holding a British consul hostage (Patrizio Gunning and Challis 550).

The blue-books were described in The Saturday Review as thick, heavy volumes “in which the whole history of the relations of England with Abyssinia is recorded” (“The Blue-Book of Abyssinia” 296). The author of the Review piece seems to agree that they are “garbled”, heavy with the excuses of its politician-authors, each unwilling to take responsibility for the “sad scrape” of the expensive expedition (296). Interestingly, the force was composed largely of British-Indian battalions.

Patrizio Gunning and Challis note a unique feature of this expedition: the inclusion of a British Museum staff member. This, they argue, proves that the “plunder of cultural heritage on the Maqdala expedition was premeditated” (Patrizio Gunning and Challis 551). And indeed, when the British-Indian troops left the defeated fortress at Maqdala, they took with them many sacred and royal objects, including the crown of the Abuna (567). This circumstance resembles Herncastle’s premeditated theft of the Moonstone. On the night before the taking of Seringapatam, he boasted to his fellow soldiers that they “should see the Diamond on his finger” (Collins, The Moonstone 3). Patrizio Gunning and Challis observe the strange repetition of the British-Indian army taking part in the looting, as “[l]ooting objects of cultural value was one of the defining acts of colonizing India” (562).

Patrizio Gunning and Challis claim that the popular response to the fall of Maqdala was “jubilant” and that the “plundered acquisitions were triumphantly reported” in London newspapers (567). Dickens’ mentions of the expedition, given without context, assume that readers were aware of these events. While “Another Species of Official Midge” is highly critical of the British Foreign Office and its preparation of the blue-books, it doesn’t comment on the expedition itself. In another issue, All the Year Round censured Emperor Tewodros, claiming that his kingdom had flourished while he “listened to the counsels of two Englishmen”, and declined when he neglected their counsel (“Amiable Theodorus” 395). This article depicts the emperor as an “oppressor” from whom his people wished to be delivered (395). We can therefore gather that Dickens was in sympathy with the expedition, despite the mishandling of the blue-books. Delving into the allusions to Abyssinia in “Another Species of Official Midge”, it becomes apparent that the theft of sacred objects, as seen in The Moonstone, was occurring on not only an individual but a national level. And this plunder was not condemned but nationally “celebrated…as evidence of success and scientific endeavor” (Patrizio Gunning and Challis 568). This raises interesting questions about how British readers would have seen the novel’s diamond, an inheritance of dubious provenance not unlike those that filled their national museums. Would they have been less likely to see an indictment of British imperialism in The Moonstone, reading it in All the Year Round?

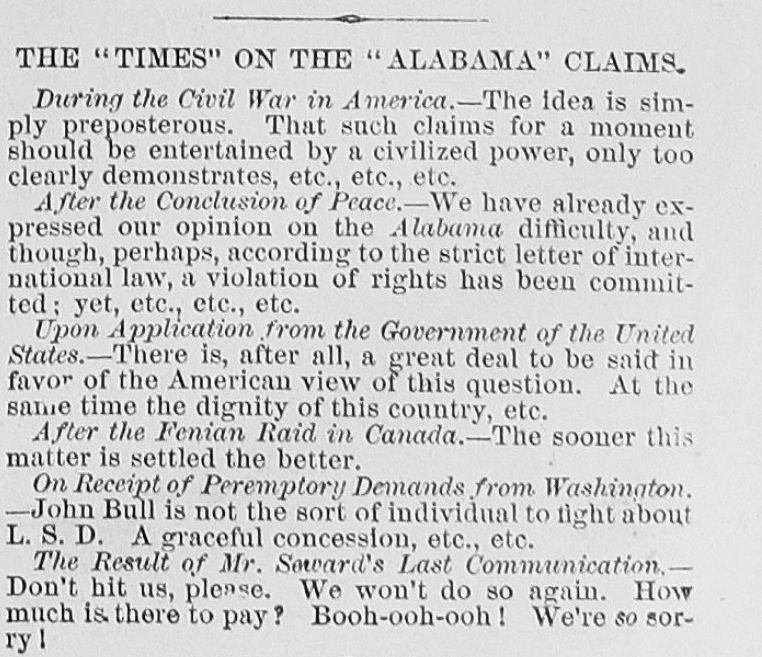

The short piece "The 'Times' on the 'Alabama' Claims" in Harper’s Weekly exemplifies American critiques of Britain in the aftermath of the Civil War. It refers to the London Times’ coverage of claims made by America; demanding Britain take responsibility for the damages caused by British-made Confederate cruisers like Alabama (“Alabama Claims”). The “etc. etc. etc.” of the first two entries implies a sort of meaningless effusiveness like that in the blue-books. Mentions of “the dignity of this country” and “a civilized power” poke fun at Britain’s self-importance. In the end, “the American view of the question” wins out over British dignity, which could not after all evade “the strict letter of the law”. The rapid descent from a “graceful concession” to “Booh-ooh-ooh” seem to make British grandiosity an absurd act, behind which is a weak and cowering nation. One of the few other mentions of Britain in this issue describes England as “terribly excited and frightened” in response to Fenian activities, a description not quite in keeping with the stoic dignity the Times has ostensibly claimed (“The Fenian ‘Gunpowder Treason” 33). Also, an earlier issue refers to the Abyssinian expedition mentioned above as one of a series of British “follies”, a reckless attempt to preserve national pride (“The Abyssinian Expedition” 661). This national reception of Britain doubtless impacted The Moonstone’s American readership, making them more prone to perceive the novel as anti-imperialist.

In contrast to the foolish Britain of Harper’s Weekly, this excerpt from “The French Press” in All the Year Round shows a Britain worthy of emulation. The gazettes published in London and the “freedom of their tone” served, according to this article, as the inspiration for French gazettes. These French gazettes, however, apparently could not live up to the freedom of the British press, being unable to “attack the ministers, as was being done in England”. This paints Britain in a very warm light, as a nation that leads the way in liberty and free speech. In fairness to All the Year Round, it should be acknowledged that the periodical is evidence in itself that Britain had a robust press, with articles like "Another Species of Official Midge" holding the government to account.

But a certain glorification of England is still is woven through this issue. In another serialized novel that appears in it, The Dear Girl by Percy Heathington Fitzgerald, French characters hold Britain in high esteem. Anglo-Irish Fitzgerald creates a French landlady who admires “all the English” (140). This character’s admiration is seconded by Dr. Favre, a French physician who is “above all, pleased with English interest” (Fitzgerald 143). Heathington reinforces the sentiment of “The French Press” that Britain inspires envy and respect in Europe.

These form an interesting contrast with “The ‘Times’ on the ‘Alabama’ Claims”, which derides British journalism as grandiosely verbose and weakly submissive by turns. In Harper’s Weekly, British journalism cries “[d]on’t hit us, please”, while in All the Year Round it stands as a revered example, reflecting their differing valuations of Great Britain as a nation, which doubtless impacted the reading of Collins’ English Novel (“The ‘Times’ on the ‘Alabama’ Claims” 43).

These stories, articles, and illustrations form the physical surroundings of The Moonstone’s third installment as it reached its original readers on either side of the Atlantic. A great deal more was recorded in these pages, from Reconstruction in post-Civil War America to the investigations of fictional heroines, and the pieces of each publication together transport us to the year in which The Moonstone was first read. In this installment, Colonel Herncastle passes on in death the diamond that cursed him in life, perhaps hoping that the symbol of his greed would taint another life. Readers did not yet know that this would precipitate the demise of Godfrey Ablewhite, or that Rachel Verinder would ultimately be left without the diamond, but with a happiness her uncle sorely lacked. And readers who pondered the correlation between Herncastle’s theft and British plunder might be surprised to learn, months later, that the displacement of the diamond is resolved with a return to its homeland and sacred purpose. It seems probable that the Harper’s Weekly skepticism of Britian’s noble self-image, in combination with The Moonstone’s illustrations, might be more fertile ground for such thought, but doubtless there were All the Year Round readers who applied the critical lens of articles like “Another Species of Official Midge” to current events like the Abyssinian Expedition, and shunned the tainted inheritance of British imperialism.

Works Cited

“Alabama Claims.” Britannica Concise Encyclopedia, Britannica Digital Learning, 2017. Credo Reference, https://search.credoreference.com/articles/Qm9va0FydGljbGU6NDU3MzE4?aid=102628.

“Amiable Theodorus”. All the Year Round, 19 Oct. 1867: pp. 392-395. Dickens Journals Online, https://www.djo.org.uk/all-the-year-round/volume-xviii/page-392.html.

"Another Species of Official Midge". All the Year Round, 18 Jan. 1868: pp. 132-135. Dickens Journals Online, https://www.djo.org.uk/all-the-year-round/volume-xix.html

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone. Oxford University Press, 2019.

Collins, Wilkie. “The Moonstone.” Harper’s Weekly, 18 Jan. 1868: pp. 37-38. Pt.3 of a series. Gale Primary Sources,https://go-gale-com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/ps/navigateToIssue?volume=12&loadFormat=page&issueNumber=577&userGroupName=ucalgary&inPS=true&mCode=96EY&prodId=AAHP&issueDate=118680118

Fitzgerald, Percy Hetherington. “The Dear Girl.” All the Year Round, 18 Jan. 1868: pp. 139-144. Pt. 14 of a series. Dickens Journals Online, https://www.djo.org.uk/all-the-year-round/volume-xix/page-139.html.

Leighton, Mary Elizabeth and Lisa Surridge. "The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper's Weekly." Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 42, no. 3, 2009, pp. 207-243. Project MUSE, https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/vpr.0.0083.

Patrizio Gunning, Lucia, and Debbie Challis. “Planned Plunder, the British Museum, and the 1868 Maqdala Expedition.” The Historical Journal, vol. 66, no. 3, 2023, pp. 550–572. Cambridge Core, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X2200036X.

“The Abyssinian Expedition”. Harper’s Weekly, 19 Oct. 1867: pp. 661. EBSCOhost, https://web-p-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/ehost/archiveviewer/archive?vid=3&sid=9afdb8fd-4f85-42fd-a35e-9b955ddbd235%40redis&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#kw=true&acc=false&lpId=divl019&ppId=divp0005&twPV=&xOff=0&yOff=194.39999389648438&zm=2&fs=&rot=0&docMapOpen=true&pageMapOpen=true&AN=66925759&db=h9m

“The Blue-Book on Abysinnia.” Saturday review of politics, literature, science and art, vol. 25, no. 645, 7 Mar. 1868, pp. 296-297. ProQuest, https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-periodicals%2Fblue-book-on-abyssinia%2Fdocview%2F9617278%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D9838.

“The Fenian ‘Gunpowder Treason’.” Harper’s Weekly, 18 Jan. 1868: pp. 34. Gale Primary Sources, https://go-gale com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/ps/navigateToIssue?volume=12&loadFormat=page&issueNumber=577&userGroupName=ucalgary&inPS=true&mCode=96EY&prodId=AAHP&issueDate=118680118

"The French Press". All the Year Round, 18 Jan. 1868: pp. 127-132. Dickens Journals Online, https://www.djo.org.uk/all-the-year-round/volume-xix/page-121.html

“The ‘Times’ on the ‘Alabama’ Claims.” Harper’s Weekly, 18 Jan. 1868: pp. 43. Gale Primary Sources, https://go-gale com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/ps/navigateToIssue?volume=12&loadFormat=page&issueNumber=577&userGroupName=ucalgary&inPS=true&mCode=96EY&prodId=AAHP&issueDate=118680118