Part 2 - Lane Sayer

The second installment of Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone was published on January 11th, 1868 in both All The Year Round and Harper’s Weekly, encompassing chapters four and five of the novel. Here, readers are introduced to Rosanna Spearman, a thief-turned-servant who has recently entered into the Verinder household as the second housemaid. With focalized narration through Mr. Betteredge’s voice, this installment introduces and connects Rosanna, Franklin, and the Shivering Sand, signalling a significance between these three parties and the titular subject of the narrative’s mystery. Rosanna is a character of great interest – physical disability, female criminality, and unrequited love across class divisions are traits that contribute to her ‘othering,’ and this perception implicates her in the theft of the Moonstone. In Articulating Bodies, Kylee-Anne Hingston writes that “the plot’s mystery is perpetuated by people’s inability to correctly read bodies and behaviour in general” (96) and how this inability is amplified in the reading of disabled bodies such as Rosanna’s. Disability is commonly seen in Victorian fiction, and it is often used as a narrative strategy to “[symbolize] social and physical deviance” (Hingston 18) within implicit characterization.

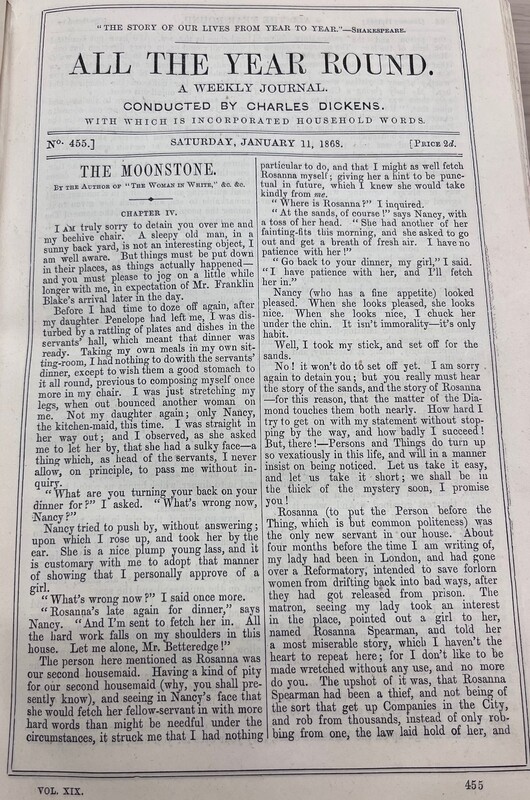

When comparing the original publications of this installment in the English All The Year Round and in the American Harper’s Weekly, a number of differences spring forth: the clearest difference being the inclusion of illustration within the Harper’s publication, and the lack thereof in All The Year Round. Hingston writes that “perception—especially visual perception—is integral to the construction of disability” (6); the illustrations add another layer of visual interpretation to disabled characters within The Moonstone. In this exhibit, I will be exploring how disability in The Moonstone can be read in differing ways according to the materiality of the two publications, and expanding upon Hingston’s narrative and thematic analyses on The Moonstone to include the impact of this differing materiality on depictions of disability.

Within the text itself, Rosanna’s autonomy is constantly undermined – yet it is still clear that she has autonomy, that she’s a complex character beyond the tropes and stereotypes of disabled characters in 19th century fiction. The first time Rosanna’s character is brought up is by Nancy, who tells Betteredge with a “sulky face” that “‘Rosanna’s late again for dinner’” (19-20). Before Rosanna is physically present or even named within the narrative, Nancy’s annoyance along with emphasizing the repetitive nature of Rosanna’s lateness establishes negative characteristics about her. Betteredge reveals Rosanna’s history, again without her physical presence. His tone is one of pity as he recalls her background and current place in the household, leaving out “wretched” details that he “[hadn’t] got the heart to repeat” within his narrative (20). Before Collins introduces Rosanna physically, he introduces her through the gaze of other characters including Nancy, Betteredge, the other servants, and Lady Verinder, and this gaze often distills Rosanna’s identity into something to be pitied or abhorred. Rosanna is stared at through these expository interactions; as disability scholar Garland-Thompson phrases it, “staring registers the perception of difference” and the depth of Betteredge’s analysis of Rosanna’s character emulates a stare through text (Garland-Thompson 56-57).

When we first see Rosanna described physically in the text, she is described by Betteredge as wearing “her little straw bonnet, and her plain grey cloak that she always wore to hide her deformed shoulder as much as might be” (23). Again, this contributes to the idea of staring, while bringing in a literal interpretation of the aforementioned phenomenon since her description has moved to physical traits rather than social or behavioural. By the time Rosanna speaks for the first time in the novel, the reader has formed many assumptions about her character due to the curious nature of Betteredge’s description, and these assumptions act as a misdirection for the mystery that is incited shortly after this installment.

The serial nature of The Moonstone means that each individual installment much capture readers as much as the entire work does; the tension Collins creates between Rosanna and her reputation is an effective strategy to draw readers in, especially in an early installment focussed on character exposition. Drawing upon Victorian literary tropes, readers will recognize Rosanna as a significant player within the story to come. In All The Year Round, the literary works are published neatly and unembellished, with two uniform columns on each page surrounded by a uniform border. The publication is mostly free from advertisements (save for an advertisement for a play created by Dickens and Collins) and illustrations, emphasizing the words upon the page. I believe that the simplicity of the serial’s layout contributes to the stare upon Rosanna in chapter IV – the plainness of the text implies a formality that may impart a tone of objectivity to the reader, especially at such an early point of the text. The simple harmony of the publication further alienates Rosanna, a character outside of Victorian femininity and ideals, a character existing outside of the bordered margins. The previous textual analysis of Rosanna’s introduction as staring at and othering her applies to All The Year Round’s publication relatively unchanged, as the text itself is emphasized more than the page.

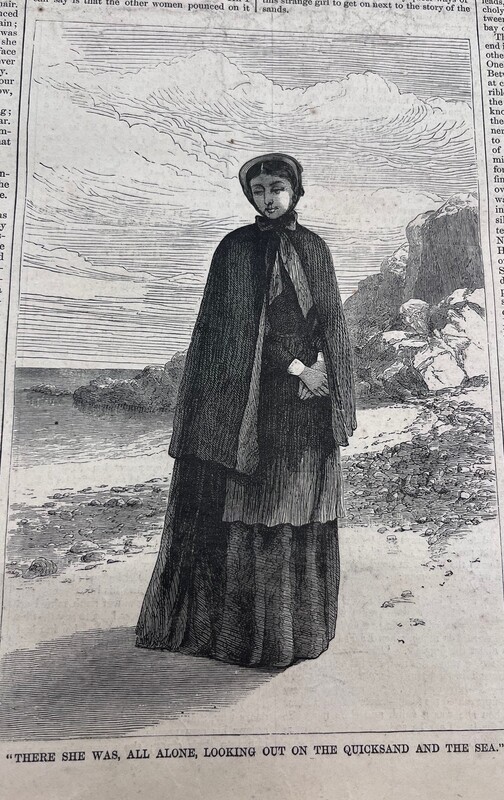

Rosanna’s introduction in Harper’s Weekly is paired with an illustration of her at the Shivering Sand. In her straw bonnet and cloak, as Betteredge described in the text, she gently clasps her hands and casts her gaze downward demurely. Her right shoulder is slightly larger than the other, but it is a very subtle distinction that could be easily missed. This illustration constitutes another instance of staring, indeed, but this illustration portrays Rosanna in a positive light, her expression kind and gentle and akin to standards of beauty. The illustration is large, occupying about a third of the page’s layout, and has a visual contrast between Rosanna and the background; therefore it is one of the first things that the reader’s eye is drawn toward. So in this publication, the reader first sees Rosanna’s portrait, then reads of her reputation, then receives Betteredge’s physical description of her. Mary Elizabeth Leighton and Lisa Surridge concur that the “visual material surrounding Rosanna in the American text de-emphasizes her disability in favour of pathos” (229) throughout the Harper’s publication; the subtlety of her physical ‘deformity’ within this illustration shifts the attention from her disability to her personhood. Therefore, the American readership likely formed a different interpretation of her as opposed to the English readership, one more sympathetic.

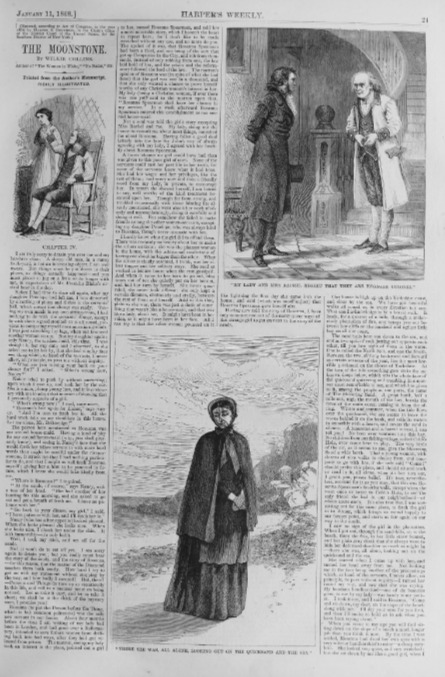

While All The Year Round established a formality and objectivity due to its uniform layout, Harper’s Weekly creates a sense of objectivity as well. The wide breadth of the content within the American publication surrounds The Moonstone with articles of train crashes in Angola, pork slaughterhouses, Christmas comics and jokes, and many other different genres and forms of print media. Rosanna’s illustration is reminiscent of a photograph, with a centered composition and poised angle. Thus, the reader primarily assimilates the illustrated Rosanna and not Betteredge’s Rosanna into their interpretation of her, and perhaps Betteredge’s unreliability as a narrator was noticeable to American readers earlier than British readers. The American readership stare at the image and see a woman standing upon sand; the British readership stare at the perceptions of Betteredge, Nancy, and all the other voices and opinions that build Rosanna as a character. The readers of Harper’s Weekly see the person before they see the disability; the readers of All The Year Round see the disability and dysfunction before the person.

Together, the two publications and their methods of storytelling change the perception of Rosanna and other marginalized characters within the novel. The Harper’s illustrators remain faithful to Collins’ textual descriptions, yet they portray characters like Rosanna, the Brahmins, and Ezra Jennings without using caricature or exaggeration. In fact, they often portray these textually scrutinized characters in an empathetic, positive way. It speaks to Hingston’s exploration of disability as “not characterized by physicality, but rather by the social, cultural, and environmental conditions…that shape the experience of that physicality to make it a disability” (12) – within The Moonstone, we can consider how the environment and cultural context surrounding these depictions affect the acceptance of disabled and othered bodies.

Works Cited

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone. Oxford University Press, 2019.

Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie. “The Politics of Staring: Visual Rhetorics of Disability in Popular Photography.” Disability Studies: Enabling the Humanities. Edited by Sharon L. Snyder, Brenda Jo Brueggemann, and Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, MLA of America, 2002, pp. 56–75.

Hingston, Kylee-Anne. Articulating Bodies: The Narrative Form of Disability and Illness in Victorian Fiction. Liverpool University Press, 2019, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvqmp1gs.3.

Leighton, Mary Elizabeth, and Lisa Surridge. “The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper’s Weekly.” Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 42, no. 3, 2009, pp. 207–43, https://doi.org/10.1353/vpr.0.0083.