Part 31 - Caitlyn Greenway

Introduction

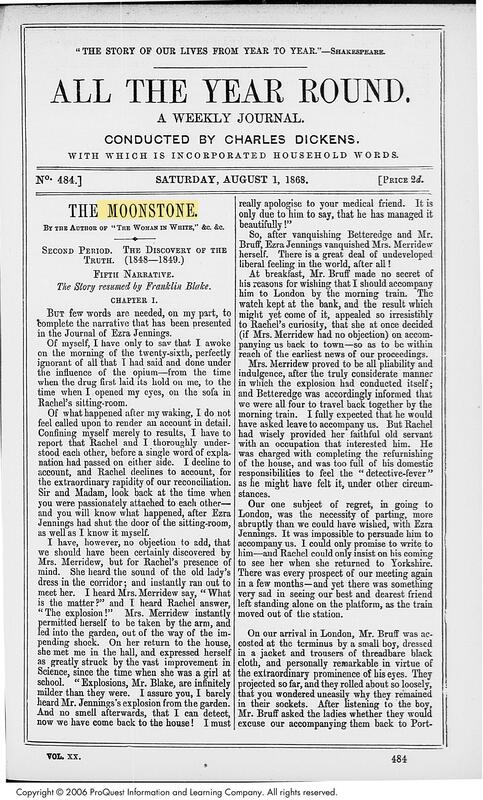

The US’s (Harper’s Weekly) and the UK’s (All the Year Round) serialization of the Moonstone have the same text, but much different interpretations. The pages of The Moonstone in Harper’s Weekly are surrounded by 18th century ads and accompanying short stories but also by illustration. This American release not also looks but can be interpreted much differently than its European counterpart. Dickens’ All the Year Round is much simpler, The Moonstone only followed by short stories, and left as just a publication of text without any accompanying pictures, or advertisements. Though at their core they are the same text, they present audiences with different pieces that influence them through each of their readings. One of the most poignant pieces of this happening is Harper’s Weekly’s illustrations, and their sympathetic portrayal given to the Indians. In which they are portrayed quite respectfully and not quite as violent. This all culminates in audiences viewing the Indians more complexly and not solely writing them off as villains in the story. This complexity also comes into play with the novel's notable critiques of hierarchy and classism in Victorian society, which is much more apparent in the American edition. The pictures paint the guilty upper-class characters in an unforgiving light, making a spectacle of their misdemeanors. All The Year Round and Harper's Weekly present readers with the same story, but the different ways in which they tell it have led to the opportunity for characters to be interpreted in vastly different ways. The American’s sympathetic portrayal of the Indian characters and detailed depiction of class conflicts, invite the reader to engage with the text in a more complex way, while the British serialization stays true to maintaining its more traditional–and hierarchical–structure.

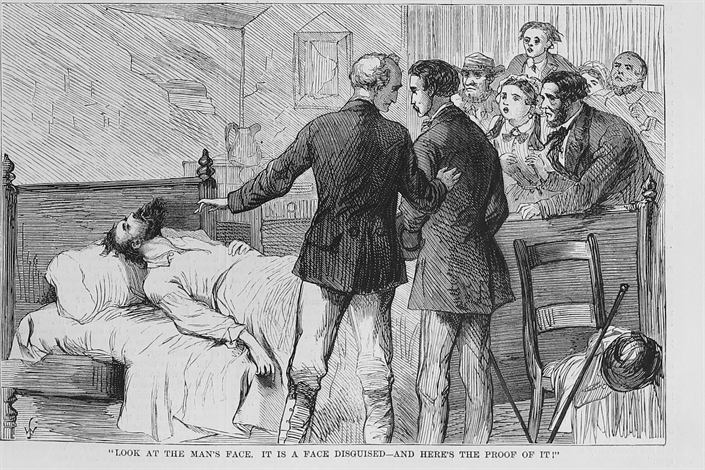

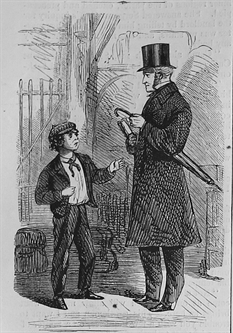

This narrative begins the story’s conclusion as it finally reveals the identity of the diamond thief, who is none other than Godfrey Ablewhite. Franklin describes the events leading up to this as they try and fail to follow the diamond being taken out of its vault and handed over to the thief Eventually Gooseberry, a boy recruited to help them search, tells them the room the thief resides in and when they enter they find him–Godfrey–dead. Godfrey is not just found dead in any condition, but found in disguise with a kind of blackface on himself to look like an “Indian” (which is how he escaped recognition as the culprit). By looking at the illustration that accompanies this scene, Godfreys murder was seemingly not a very violent one. He is shown to be laying in bed, leading the reader to interpret that he was likely murdered in his sleep. Along with everyone complicit in stealing and keeping the diamond from the Indians, Godfrey also exploits them by presenting himself as one of them. As Leighton and Sunridge describe, “Ablewhite is portrayed as a cultural thief” (231). Though the novel, on the surface, plays with the idea of the Indians being potentially responsible for stealing the diamond, it is always emphasized that they either did not when they were suspected, or could not have. Though characters suspect them, even irrationally claim them to be overly suspicious and dangerous (when they are shown to not be very much of either) the true actors of ill-will and bad actions, are the white upper-class victorian characters. Franklin is the character who initially steals the diamond (even though not intentionally), Mr. Candy drugs him which causes him to, Godfrey actually steals the diamond, and his partner Mr. Septimus Luker aids him in stealing it. The novel continuously underscores a criticism and critique for the upper class.

Throughout The Moonstone, the search for the diamond is not only a key plot point but also serves to highlight the novel's critiques of Victorian society and hierarchies. The hunt for the diamond is filled with misdirection and misjudgement, where the characters are constantly accusing and assuming each other to be guilty based on class, race, gender and/or disabilities. The constant tension and blame to one another seems to emphasize the Victorians projecting their prejudices and anxieties onto people that do not fit within their rigid social structure. In Harper's Weekly, the illustrations serve to show a more potentially nuanced perspective, as Leighton and Surridge put it, “providing jarringly disparate points of view, the illustrations refuse to endorse a straightforward notion of narrative perspective, instead highlighting … multiple and ideologically distinct points of view,” (217). Though the characters have blamed and been wary of the Indians, they ultimately are a cover for what is really happening. Which mirrors Godfreys disguise. They are looking for an Indian, when in reality it is one of the upper class members who has committed the crime. This obsession with the Indians does not only appear in the characters' haste to frame them as the thieves, but also in mystifying the supernatural abilities–and curse–that the “Indian” diamond possesses. The English characters are quick to use these foreign concepts and people to project their prejudices. They spend so long ruminating about the idea that the Indians are the thieves, they are shocked to find out for certain that the thief is one of their own–Godfrey Ablewhite. This pointing of fingers brings out the Victorians hypocrisy, where the rich are not given the same scrutiny that those not as privileged are.

All The Year Round’s simple and non-illustrative paging is very much a mirror to the rigid system of the Victorian society in which it was published. While the readers in America are freshly out of the civil war, and more likely to be “radical” in their ideas (when compared to the UK). The noisy magazine with ads and pictures is distracting compared to just the bare text of the novel in this edition. Although, this edition is not completely deprived of other narratives as the accompanying stories after this narrative follow stories set across the world. Though these stories are present in this serialization they serve multiple purposes. They reflect the imperialist mindset of the Victorians, by showing far away lands and cultures through their own lens of exploration, publications which cater to the audience reading them. But, including stories of any kind set outside the British isles does also help to raise a more broadened and global perspective to readers. These narratives help to strengthen the reader's connection to the world, while it may not be as busy as Harper's Weekly, it still allows new stories and ideas to present themselves to the Victorian reader. Though, this presentation is much more expansive in the American edition, as Leighton and Surridge remark about the effect the illustrations add, “the negative portrayal of the Indians changes in favour of positive iconography: even more than in the unillustrated novel, they are depicted as ‘committed, religious figures’ who stand as ‘morally superior’ to the British diamond hunters” (231). Ultimately, this shift showcases the way that the different audiences are inclined to think about the texts, which are shaped by the cultures they are surrounded by.

An important feature of the Harper’s Weekly magazine is the presence of current events and news coverage that comes along with the short story segments. These sections would have been influential for readers, and made them more engaged with critically thinking about the novel and the themes present in it. The presence of the sympathetic drawings further demonstrate this engagement, as the reader is encouraged, or perhaps naturally guided, to think beyond the confines of the story and relate it to the current events they’ve just previously read about. While “All the Year Round” also has varying stories from varying regions, these actual (non-fictional) news stories would be even more engaging. It makes the contents of the story feel more real, fiction surrounded by non-fiction. Reading is inherently political in nature, and stories even when fictional have gravity to them and can be influenced or affected by reality. The story’s critique of the Victorian upper class, feels even more prevalent when it is surrounded by news headlines, potentially also critiquing actions done by the Victorian upper class. The contrast between the fictional story of The Moonstone, and real coverage of events taking place creates an interesting context for the stories to exist within. By being placed next to these stories, Harper's Weekly reminds the reader of the context in which the stories are taking place, that they do not exist separate from reality but rather are informed by and built upon it. The inclusion of current events, and especially ones that critique actions of the upper class, make the reader think more critically about the content in which they are consuming. The illustrations again further this, with their more nuanced depiction of events. By reading both the factual and fictional stories that the US’s serialization delivers, the story becomes an even more powerful tool for social commentary that it is trying to argue.

Conclusion

This passage is found at nearly the end of The Moonstone, as Franklin Blake's final narrative not only reveals the diamond thief but gives more insight into the characters feelings of betrayal that come with the reveal. This piece of the narrative finally resolves Franklin as innocent in the crime of stealing the diamond, and finally implicates the real culprit. There is also a sense of wonder left to the reader, as we never see for certain what happens with the Moonstone. Though the reader knows that the Indians have reclaimed it, and that they will likely return it to where it belongs. This ending is notable as it is very unlike reality, where the stones taken by the British were never returned to their home. Still resting in British museums, not in their original locations. The novel not only critiques the injustice of colonial exploitations, but also shows a hopeful idea where those wrongs are righted.

Works Cited

All the Year Round, vol. 20, no. 484, 1868, pp. 176.

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone. Penguin Classics,1999.

Harper’s Weekly, vol. 12, no. 605, Aug. 1868.

Leighton, Mary Elizabeth and Lisa Surridge. "The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper's Weekly." Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 42 no. 3, 2009, pp. 207-243.