Part 30 - Sophie Anning

As a work of sensation fiction, it is only fitting that The Moonstone have not just one but two very sensational serials. Both the American serial and the UK serial engage with stimulating writing, but each has its own priorities that contribute to some differences in the audience experience. The American publication in Harper’s Weekly was focused on high quality writings alongside “visually arresting” illustrations to engage and entertain as much of the reader’s mind as possible, creating emotional responses and connections between the entire serial production and the reader (Leighton and Surridge 209). The UK Publication in All The Year Round prioritized an active sense of reading that involved the readers in the process of creating meaning through multiple texts through tessellated readings, focusing on intellectual development and prowess in the reader, allowing them to create their own interpretation of the text (Lanning 8). These focuses are particularly present through Part 30 of Wilkie Collin’s The Moonstone, where the excitement of Ezra Jennings’ opium experiment on Franklin Blake is published alongside entertaining opinion pieces and educational articles. The American and UK publication contexts of The Moonstone are significant because the different priorities of the written word and illustrations in each serial created a different audience experience for American and British readers.

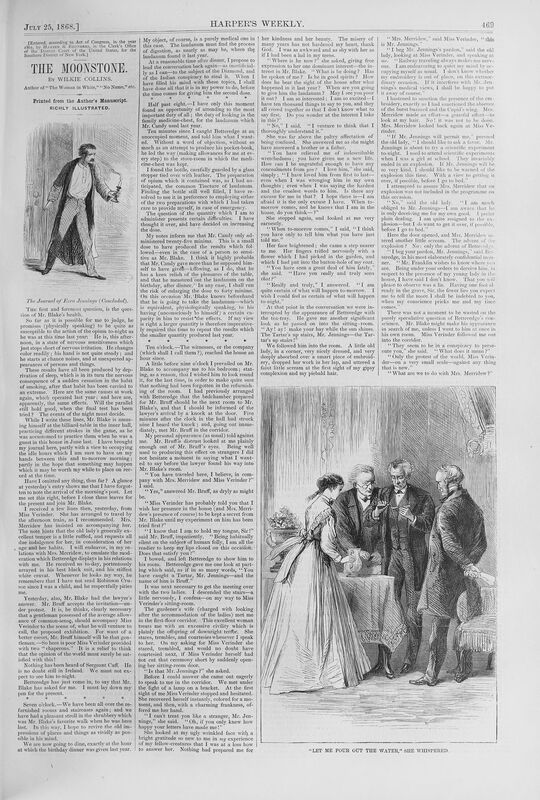

This image is the second of two that accompanies Part 30 of The Moonstone as an illustration of events in the story. A highly detailed and well-crafted image, it is focused on the scene where Mr. Jennings, Mr. Bruff, Mr. Betteridge, and Miss Verinder are creating the laudanum solution to give to Franklin Blake. The three men look very serious, all frowning and straight bodied in the image, with Mr. Jennings in the centre concentrating heavily as he pours the opium onto a spoon. Miss Verinder appears curious, with a leant-forward body holding a water pitcher, and the image is captioned with her asking to pour the water into the solution as a way for her to participate. The image is large and placed in the bottom left corner of the page, intending to be the first place that a reader’s eyes divert to before reading the story.

This illustration is an excellent example of Harper’s publishing priorities and the effect this has on its audience. As the reader enters the part of The Moonstone where they will find out whether Franklin Blake took the diamond, their excitement is already heightened by the “nervous sensitiveness” of Franklin Blake in the passage, and the grave seriousness of the characters in the illustration is combined with this emotional response because the character’s seriousness is then shared by the reader over whether Blake will provide the result desired (Collins 411). Illustrators worked hard with sensation fiction to create images that reflected the anticipation of what would happen next using techniques such as “the use of white space to create ghostly effects” that are present in this illustration to heighten the senses and reflect the seriousness and nervousness of the characters in the experiment, working to engage the reader with the story through providing a visual representation to create emotion of curiosity (Leighton and Surridge 209). The priority placed on the excellence of accompanying illustrations shows how Harper’s desire to engage and entertain their audience with a combination of written and illustration created a reading of The Moonstone that was far different from the UK readers’ experience of just the written word.

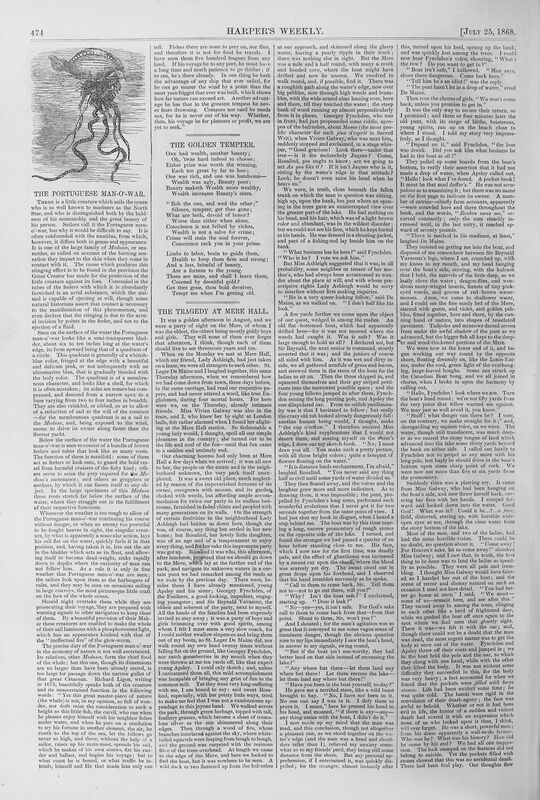

This illustration on page 474 points to Harper’s prioritization of highly engaging material both through its image and through the accompanying writing. The writing is about the Portuguese Man-O-War, a jellyfish-like sea creature primarily in Pacific water characterized by a bright blue bladder-like bulb and long tentacles with the ability to sting (Harpers 474). The illustration is highly detailed, with an evident focus on providing an image as close to the physical animal as possible for the reader to truly understand just how strange this creature is. The writing that accompanies the illustration is written as an informative piece with the intent to engage the readers in some trivia alongside providing information on a fascinating creature that most readers of the Victorian Era had never seen.

This illustration points to Harper’s desire to give the reader an entertaining experience with illustrations and words which would create an exciting reading of The Moonstone. By publishing a piece about an exciting and foreign object of scientific interest with a detailed image right beside a part of Collins novel that discusses a scientific experiment where precision is key, the readers emotional connection with the text is heightened and The Moonstone also feels exciting. The reader forms a subconscious connection with the biological fascination of the Man-o-War and the science laden, experiment-driven portion of The Moonstone as products of curiosity, thus creating an experience where the reader is primarily entertained by the literature itself while interacting with very real scientific experiments that involved the “pouring” of materials and measuring “minims” and “parts” (Collins 420). This reflects Harper’s priority of “the interplay of visual and verbal text,” where the reader interacts with the words on the page alongside the images to develop an interactive and emotional reading of the text by engaging the reader with a piece about a biological anomaly and then associating this with an exciting story involving a chemical experiment on a human (Leighton and Surridge 210).

This writing on the positives of drinking the tea produced from Mahogany tree leaves is an excellent example of All the Year Round’s prioritization of tessellated readings for its audience. The work begins with a musing over how great writers such as Shakespeare, Spenser, and Milton could have written their works without the comfort of tea and transitions into a very long exploration of the origins and uses of all kinds of tea (All the Year Round 153-157). This writing focusses heavily on the ancient origins and myths surrounding tea in China, discussing Brahmins, devotion, and Dharma as components to the creation and use of tea (All the Year Round 154).

This writing contributes to All the Year Round’s focus on tessellated reading through its topic and subsequent relationship to The Moonstone. The writing was published right after Part 30 of The Moonstone and the focus is on the effect of a plant on the body, which layers on the section of The Moonstone that specifically deals with opium stimulation. The audience would read Part 30 and then read this piece on the effects of a tea plant, creating a multifaceted reading of Collin’s story by comparing and relating the effect that tea has compared to a foreign substance such as opium in the story. The reader becomes involved in layering text upon text, comparing the relaxing effects of tea and the “stimulant influence” of opium between the two readings and intermingling with fiction and non-fiction, and it is this closer reading of the texts in the serial that creates the engagement that All the Year Round desired (Collins 423). The description of the effects of the opium on Blake serves to further this engagement, with the “stimulant influence” and “contracted eyes” offering verbal imagery to the reader that engages the connections by providing specificity of effects that “Mohogany Tree” does with tea making the two works side by side comparisons of two different substances (Collins 425-426). The engagement was focused on having the reader make connections between texts, and as such, a UK audience has a tessellated reading of the text focused on the verbal descriptions within the written word.

This opinion piece written on the general Militia experience is a representation of the tessellated reading prioritized by All the Year Round. This piece reads as very sarcastic and frustrated, written by a young officer of the British Army who is critical of the training he has received and of those who presided over his training. He cites frustration with the perceived feigned gratitude that “Her Majesty” has for each individual soldier in their commission, alongside the quality of uniforms, the food at the mess hall, and the leadership of his senior officers (All the Year Round 158). The piece takes up eight total pages of the publication and is without images beyond those that the reader imagines.

This section of writing speaks heavily to All the Year Round’s priority of a tessellated reading experience. As it is placed further in the publication after The Moonstone, a reader is most likely to read this work after having completed reading about “The Experiment” and the discoveries made in Part 30. The theme of militarism is heavy in “The Moonstone,” with the Diamond’s origins rooted in the military conquests not just of the British Empire but of a single man over the Brahmin Priests in the Temple (Collins 14). This continues throughout the text with the Diamond as the centerpiece of this militaristic conquest, but the theme transcends into other areas such as the foreign educations of Blake and Jennings, even down to the opium used for “The Experiment,” which itself is a product of militarism. Throughout reading the piece, the reader would compare their knowledge of these conquests with the author's opinions, “actively rearranged the ideas embedded within each periodical to reach a unified meaning from the reading experience” (Lanning 1). The unified meaning would be individual each reader based in their positionality and intersectionality, but the tessellated reading experience would exist, nonetheless. Overall, the position and topic of this piece clearly shows how All the Year Round prioritized a tessellated reading experience, creating a thoughtful and critical reading experience for its audience.

As one of the final parts of The Moonstone, this section of the serial carries a lot of weight with the reader as the story is nearing its conclusion. The reader has been on a journey throughout the last 29 serials and, depending on which serial they have read, has experienced a combination of the verbal and illustrative or a focused tessellated reading of The Moonstone that has been exciting and educational. Part 30 encapsulates the sensationalism of the novel that Victorian readers enjoyed into just a few pages, working towards the conclusion of the story with an intense, dramatic, nervous experiment involving exciting substances and mysterious reactions to aid in finding a lost object of foreign mystery. The serials that The Moonstone was published in did much the same to aid in the sensationalism, with the UK priority of the written word and the American priority of combining the visual and the verbal creating significant reading contexts that, although very different, contributed to the overall sensationalism through providing readers with engaging surrounding texts to aid in their experience. It is crucial to understand the context that a work is published to get a better idea of the author's perspective and inspirations. By understanding the publishing priorities of All The Year Round and Harper’s Weekly, one can grasp the way a Victorian reader would have engaged with the text and form an overall comprehensive and considerate reading that involves the past and the present.

Works Cited

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone. Oxford University Press, 2019. Print.

Lanning, Katie. “2011 VanArsdel Prize Essay Tessellating Texts: Reading The Moonstone in All the Year Round.” Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 45, no. 1, Mar. 2012, pp. 1–22. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1353/vpr.2012.0003.

Leighton, Mary Elizabeth, and Lisa Surridge. “The Transatlantic Moonstone : A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper’s Weekly.” Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 42, no. 3, Sept. 2009, pp. 207–43. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1353/vpr.0.0083.

Unknown Author. "Down With The Militia." All The Year Round. 25 July 1868, pp. 157-162, Dickens Journals Online, ProQuest, https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-periodicals%2Fout-with-militia%2Fdocview%2F7852306%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D9838.

Unknown Author. “Leaves From the Mahogany Tree.” All The Year Round. 25 July 1868, pp. 153-56. Dickens Journals Online, ProQuest, https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-periodicals%2Fleaves-mahogany-tree%2Fdocview%2F7881224%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D9838.

Unknown Author. “’Let Me Pour Out The Water’ She Whispered.” Harper’s Weekly. 25 July 1868, p. 469. American Historical Periodicals from the American Antiquarian Society, link-gale-com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/apps/doc/PANQDB956264817/AAHP?u=ucalgary&sid=bookmark-AAHP&xid=6e7bb302.

Unknown Author. “The Portuguese Man-O-War.” Harper’s Weekly. 25 July 1868, p. 474. American Historical Periodicals from the American Antiquarian Society, link-gale-com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/apps/doc/PANQDB956264817/AAHP?u=ucalgary&sid=bookmark-AAHP&xid=6e7bb302.