Part 9 - Finley Matthews

Chapter fifteen of Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone sees Sergeant Cuff continue his investigation while being accompanied by Gabriel Betteridge. Cuff still suspects Rosanna is involved in the disappearance and continues to follow up on clues, ending with a visit to Mrs. Yolland. This chapter was published on February 29th in both Harper’s Weekly in the United States and in All The Year Round in the United Kingdom. Looking at both publications, many differences are immediately visible. Looking at both versions, it is evident that the two magazines are trying to capture the attention of different audiences, and value different aspects of Collin’s work. Despite the content of The Moonstone being identical, the presentation is not. By looking at both publishers, we are shown the differences in the literary worlds of both nations and what type of readers were consuming these stories. Examining the formatting of the chapter, the presence or lack of illustrations, and the advertising, we are given a fascinating glimpse into the literary culture of the time in both America and England. In examination of Harper’s written by Jennifer Phegley, they state “Sentimental literature was often characterized in the magazine as a weak and feminine form that would destroy the nation’s ability to create its own high literary culture.” (Phegley 78). With this knowledge, it is curious to look at the presentation of The Moonstone, as the text features numerous female characters, depictions of disabilities, and notably the concept of Queerness found within the narrative has been examined by countless scholars. Despite both journals following along with the same investigation of the stolen moonstone, the readers that make up those readerships may have been quite different, and the elements of the narrative that they were interested in were equally different.

Looking at All The Year Round, the format in which The Moonstone was published is visibly different from how it is found in Harper’s. There is no credited author, with the byline only indicating a separate work by Wilkie Collins. Instead of displaying the author's name, Charles Dickens is the only name to appear (outside of a Shakespeare quote). This obviously demonstrates the immense popularity of Dickens during this era, dramatically overshadowing other writers, but it also represents how literature was viewed at the time. Despite already being a celebrated writer with the success of The Woman In White, Collins does not hold the same acclaim or draw held by Dickens. By having Dickens so prominent on the page, it appears that he is the main draw of the journal, not the other authors found within. People were not purchasing All The Year Round for Collins’ name, but because of Charles Dickens’ stamp of approval. Having Dickens as the draw of the journal would likely aid in getting literature published that otherwise might not have been, but it is interesting when dealing with a writer like Collins that had already seen success. This could be perceived in many ways; such as simply a symbol of the popularity of Dickens, but I believe it represents a larger preference for stories rather than following the larger oeuvre of authors.

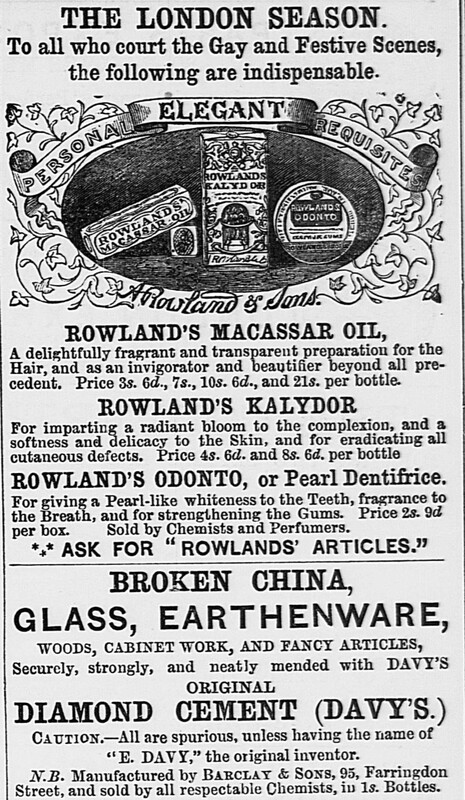

Shifting to the rest of the journal, the advertisements showcase products geared towards a wealthier population. Beauty products like hair oil and teeth whitening toothpaste were being marketed to a clientele that attended ‘festive scenes’, something reserved for people of higher status. This higher status iconography is utilised in the advertisement found directly below it, as we see an ad for a form of cement marketed to repair broken objects described as ‘fancy articles’. The name diamond cement also includes the imagery brought forth by the word diamond, signalling ideas of wealth and shimmering beauty. These items are not being marketed as everyday essentials, but as tools to enhance and repair one’s glamour.

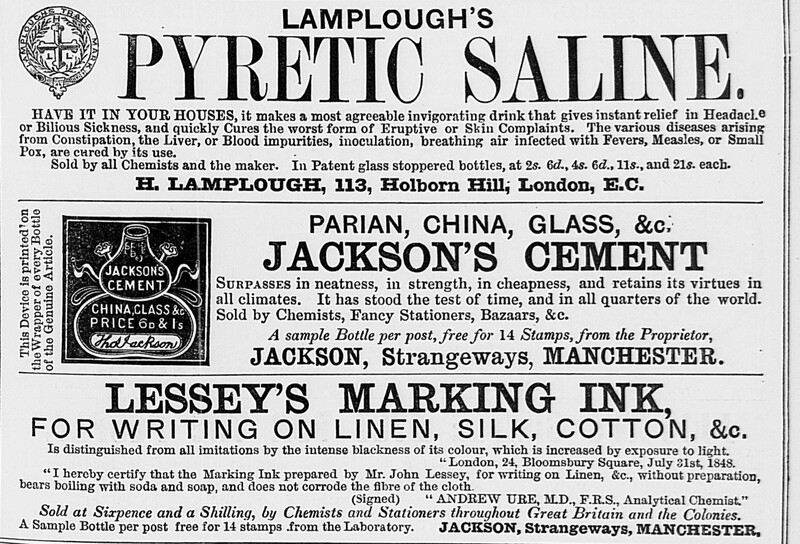

The advertisements in All The Year Round do not just cater to the elegant upper class, as some more general products are depicted. This grouping of three separate advertisements demonstrate less extravagant items. One for a medicinal drink to relieve symptoms of illness, one for a cheap repair cement, and an ink for writing on fabric. The language used in these ads does not attempt to instil a sense of luxury, but instead markets the items as essentials. These ads give a more rounded view of the audience of All The Year Round; skewing slightly more to a female audience with the beauty products, but not completely attempting to market solely to women. Outside of the beauty products, the advertisements take a gender neutral approach. The ads found within the journal tend to lean into a sense of beauty and physicality. This preference for beauty can be seen with how The Moonstone is depicted; as the semantics of the book are not being explored, rather focusing solely on the narrative. Wilkie Collins is not being viewed as importantly as the richness of the text.

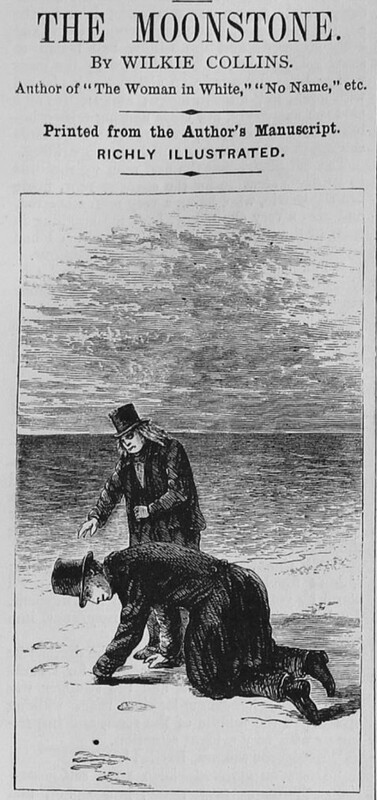

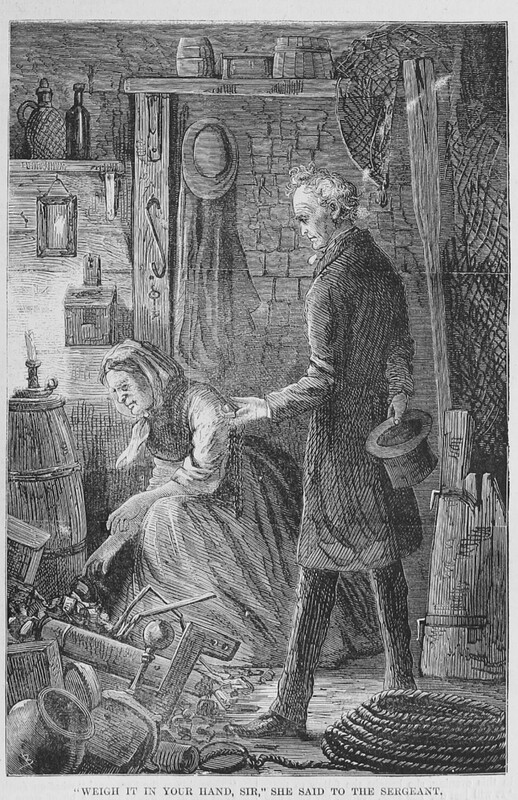

Harper’s showcases The Moonstone in a more expected format. Importantly, this version includes Wilkie Collins writing credit, and lists two of his other works. This inclusion of his name can be taken in different ways; either it represents a stronger popularity of Collins in the States, or more of a respect for authors than in Enlgand’s All The Year Round. The most visually striking difference between this version and the one seen in All The Year Round is the inclusion of two illustrations. The first depicts Sergeant Cuff bringing Betteridge’s attention to their footsteps on the beach, and the lack of any sign of Rosanna Spearman. Having this image at the beginning of chapter 15 sets the tone for the following section of the narrative. The illustration showcases the ongoing investigation and reflects the overall atmosphere of this chapter.

The above image is labelled with a quotation from the text, making it clear what event from the narrative it reflects. The only comment given for the images is a small quotation describing them as “Richly Illustrated” (Harper’s Weekly 133). It could be argued that the presence of these images provide for an elevated reading experience when compared to what is found in All The Year Round. The detailed illustrations provide a deeper glimpse into the world of the text, but the facet it is representing is simply the investigation. Both of the illustrations are concentrated on the practical investigation and the examination of clues. They are not fully visualising the world of the narrative and the rich characters found within. When compared to the presentation found in the UK, the US appears to be more elegant, but it can be argued that the illustrations convey a sense of practicality, simply demonstrating the investigation. The formatting aligns with this as All The Year Round has the chapter spread out over six pages, while Harper’s has the text condensed to try to take up as little space as possible. This has the effect of the story feeling cramped, where in the U.K the story is given room to breath.

The advertising found in Harper’s Weekly stands out as it is directed specifically towards men. The ad that specifically addresses men is for a woodworking tool; an item used for manual labour and not associated with the high class status seen in All The Year Round’s advertisements. The ad directly below it is for a patent office, specifically addressing inventors seeking to patent their creations. These ads reveal a vastly different potential readership than in the UK. When looking at this with the knowledge of the journal's potential disdain for femininity, the advertisements are aligned with this attempt to cater to a more masculine audience. There is potential that the themes found within The Moonstone were overlooked as the book was not American, so it would not reflect poorly on the American literary culture. Looking at the context surrounding Harper’s, it is possible that The Moonstone was being viewed more simply as a detective story, while in the UK it was being seen more as a character examination.

Both journals demonstrated a different format to experience the story of Collins' The Moonstone. All The Year Round took a more general approach to the text, in both audience and format. The journal appeared to be marketing itself to a wide audience in terms of gender and class. The formating of the text takes it a step beyond generality as the chapter is given multiple pages to breathe; reading more like a novel as opposed to an article. The exclusion of Collin’s name can be viewed as aiding this, with the story standing on its own, not propped up by the accolades of its successful author. Harper’s demonstrates a very different approach. The text is condensed into taking up as little space as possible, with the accompanying illustrations depicting solely the investigative angle of the narrative. The rest of the journal indicates a male audience, and the article by Phegley reveals a certain disdain for femininity. The Moonstone contains a spectrum of representations of femininity, so the inclusion of it in Harper’s is a puzzling decision. I argue that All The Year Round was more interested in showcasing the rich narrative or Collins’ work, while Harper’s was more concentrated on the surface level detective story. The chapter was identical in both publications, but both publications were anything but.

Works Cited

Phegley, Jennifer. “Literary Piracy, Nationalism, and Women Readers in Harper's New Monthly

Magazine, 1850-1855”. The Ohio State University Press, vol. 14, no. 1, 2004, pp. 63-90.