Part X - Chapter's XVI and XVII, Taylor Little

In chapters XVI and XVII of Wilkie Collin’s The Moonstone, the plot of the stolen diamond, the moonstone, thickens as Sergeant Cuff approaches finding the thief. He is convinced that Ms. Rachel Verinder has stolen her diamond, which was given to her by her uncle, Sir John Herncastle. Herncastle possessed the diamond after fighting for the English army in India in the late 16th century. This leads most novel critics to lean more into British imperialism and colonist themes; however, this is not the only prominent motif that came out of Collin’s The Moonstone. Additionally, there are more layers to Collin’s novel than at first glance. While we have the privilege in the contemporary day to read the story in a sitting, the original release of The Moonstone was done through periodicals – releasing the narrative in segments through the popular British newspaper All the Year Round by Charles Dickens and its American counterpart, Harper’s Weekly: A Journal of Civilisation. Chapters XVI and XVII were released on the same day, March 7th, 1868. Despite telling the same narrative, the two mediums in which Collin’s novel was told illustrate different interpretations and how significant moments differed amongst their respective audience. Mary Elizabeth Leighton and Lisa Surridge, in their essay “The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper’s Weekly,” go so far as to say that “The Harper’s illustrations formed an intrinsic part of the American Moonstone, heightening the texts sensationalism, complicating its already intricate narrative structure, and shifting its treatment of gender, disability, class, and race” (207). Leighton and Surridge’s argument could not be justified without looking at the text in its original printing and analyzing the elements surrounding the text that further problematize the complex, multi-perspective narrative. Similarly, I will attempt the same analysis by looking at elements surrounding the text to inform my argument. In this essay, I argue that Collin’s characters are symbolic representations of knowledge and that accessibility to information was being explored more liberally.

Contained inside All the Year Round, chapters XVI and XVII of Wilkie Collin’s The Moonstone was a poem named “Red Hugh,” written by an unknown author. Inside the poem's plot, the author details a love triangle, not too far off the one presented in Collin’s narrative. A woman named Alice, and two men who seek her hand, Hugh and the poem's speaker. The poem's speaker admires Alice deeply, but she seems to choose Hugh at every crossroads. Because of this, the speaker decides to murder Hugh, giving homage to the poem's title. Consequently, Alice begins despising and rejecting the poem's speaker, even though she was initially attracted to the speaker and not Hugh. This is symbolic for a few reasons, but most prominently, it can be considered a representation of the love triangles Collins outlines Rachel, Godfrey, and Franklin Blake, but also Rosanna, Rachel, and Franklin Blake, the difference being gender role reversal. In this case, Rosanna could be Hugh, with Franklin Blake being Alice and Rachel being the poem's speaker. Initially, the poem does not seem to consider thematic knowledge; however, it manifests as a secret, the same as the love triangle plots created by Collins. Alice has autonomy of knowledge, privatizing the information about whom she favors, which the two men are unaware of. In seeking that knowledge, the poem’s speaker kills Hugh to eliminate all other possibilities, creating a linear pathway to understanding the secret. Collins does the same in his narrative, illustrating through Betteredge that the mystery of the Moonstone, wrapped up in the love triangle between Rachel, Rosanna, and Blake, is like “liquor, and makes me wild” (Collins 139). Pursuing knowledge can then be characterized as emphatic, lustful, and dire. Therefore, “Red Hugh,” when read beside the narrative of The Moonstone, creates a dynamic where accessibility to knowledge creates tension, which is informed by the romantic plot and manifests as a craving. This can then be used to characterize a part of the historical atmosphere of Victorian society – as accessibility to information became more apparent, the desire for knowledge became more intense.

Regarding accessibility to information, The Moonstone describes the increase in the accessibility of knowledge well. The different genders, classes, and ethnic backgrounds contain knowledge via secrets, and mysteries are abundant. However, a news post from Harper’s Weekly further exemplifies this. A news post section of the periodic notes “Educational Reform in France” depicts further accessibility to women through teaching. The post establishes that education was previously done through Romish church authorities and is now accessible to women outside of that sphere through lectures given by male teachers. The lectures themselves are known as cours. This movement towards knowledge becoming more accessible is reflected in Collin’s narrative through Rachel, Rosanna, and Penelope. These female protagonists are symbolic of women progressively getting more access to education in Victorian society, and in Rosanna’s case, having more authority over the distribution of that knowledge than men do through her secret regarding the diamond. For Penelope, Betteredge is struck by how she worded Rosanna’s disassociation; “There was something in the way Penelope put it which silenced my superior sense. I called to mind, now my thoughts were directed that way, what has passed between Mr. Franklin and Rosanna overnight” (141). In this way, a reversal of who the most competent person in the room occurs – knowledge about Rosanna's love interest. Betteredge is struck by silence in how Penelope can articulate what is conditioning Rosanna to act strangely. Rosanna knows precisely what happened to the diamond; however, the reader is unaware that she knows who the thief is. Betteredge notes “a curious dimness and dullness in her eyes. . . Possibly it was a misty something raised by her own thoughts” (141) when seeing her dust with a broom. An interpretation of what Betteredge sees is that her mind is thinking about how best to prevent Sergeant Cuff from accusing Franklin Blake of stealing the diamond. Rosanna, too much of Collin's discredit, is knowledgeable. She avoids creating suspicion of Franklin Blake and keeps Sergeant Cuff on her tail the entire duration of his stay at the Verinder’s residence. The knowledge of who the thief is eventually taken to her grave.

Another way that The Moonstone conveys symbolic knowledge is through the differences between Rosanna’s home and the Verinder household. This part of the text is subtle, but the differences between the two locations are emphasized in its British publication. The periodical in All the Year Round includes “Chaucer – English in Dales.” In this advertisement, the author highlights Chaucer’s use of what they call the “Cumberland” dialect. This is seemingly irrelevant to the plot of The Moonstone; however, it conveys that knowledge can be found in places unfamiliar to the self. In Colin’s novel, a distinction between geographical locations is made early on – that is, the difference between what is known as the “Sands” and Lady Verinder’s household. We are not told much about the Sands in the novel, but due to its characterization, it is fair to say that it is a place less abundant than the Verinder estate. The Sands in the book is a rural environment, residing on the coasts of Yorkshire, and is the home of Rosanna. There, a character named Limping Lucy is her caregiver. The novel first describes the Sands in chapter XVI, noting through Sergeant Cuff and Betteredges’ conversation that “There was a coincidence this evening, between the period of Rosanna Spearman’s return from the Sands and the period when Miss Verinder stated her resolution to leave the house” (136-7). This quote outlines the two places where the plot will unfold in Betteredge’s recount. However, the reader is eventually made aware of how the secret of the diamond does not reside in the Verinder residence but in the Sands. In this way, the Sands can be considered a representation of “Cumberland” in the periodical. Both are treated as rural locations with seemingly uninteresting characteristics, but they contain unfamiliar knowledge that wants to be discovered. Collins uses the characters and specific environments to differentiate where knowledge is located.

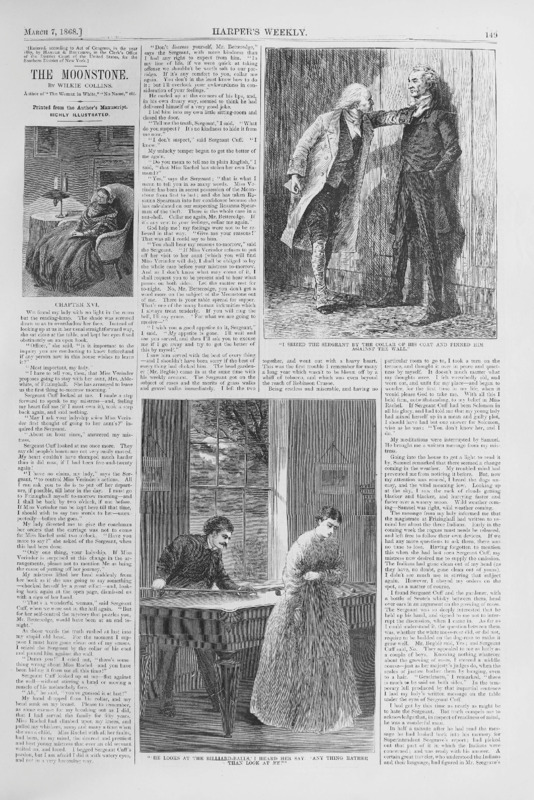

Perhaps the best insight we have into The Moonstone is its illustrations, which first appeared in Harper’s Weekly magazine and is the cornerstone for Mary Elizabeth Leighton and Lisa Surridge’s analysis of Collin’s novel. For my analysis, an exceptionally provocative illustration highlights secrecy and the desire for knowledge and truth. This illustration depicts Betteredge and Sergeant Cuff. Cuff has silently implied that Rachel Verinder had stolen her diamond. Betteredge “seized the Sergeant by the collar of his coat, and pinned him against the wall” (130). The illustration by the unknown author manifests in the audience a clear image of what kind of man each of them is. Betteredge is elderly but proper, indicating that this moment is rare, while Sergeant Cuff is middle-aged and exudes confidence. Sergeant Cuff is taking a wide-birthed stance, while Betteredge’s posture is small. The most interesting artistic choice created by the illustrator is like that of Surridge’s and Leighton’s analysis of Ezra Jenning’s illustration. Surridge and Leighton write that “[The] use of light emphasizes the sympathetic characteristics of cognition and knowledge” (234). In the illustration of Betteredge and Sergeant Cuff, the same technique is employed – both characters have similar shading across their face and foreheads. This further extenuates both the characters' heads and the knowledge they carry, with their posture indicating who holds the most knowledge, Sergeant Cuff. Throughout chapter XVI, Betteredge constantly iterates his desire for the truth from Cuff, mentioning “tell the truth Sergeant!” and “Do you mean to tell me, in plain English,’ I said, ‘that Miss Rachel has stolen her own diamond?’” (Collins 130). Throughout Betteredge’s narrative recount, his knowledge about the events significantly increases through his interactions with Sergeant Cuff. He notes that Sergeant Cuff is correct, comparing him to Soloman (131). In depicting the two through this illustration, we see a blending of knowledge between Sergeant Cuff and Betteredge. One might consider that Betteredge would have limited knowledge due to his social standing as a butler. However, when analyzed beside Cuff, he keeps up with him regarding the mystery of the stolen diamond. This strangely configures the narrative, subverting the expectations that knowledge would only be privileged by the upper-class and professional spheres.

Wilkie Collin’s The Moonstone intricately explores the themes of knowledge and accessibility within the context of Victorian society. Through characters like Rachel, Rosanna, and Penelope, Collins illustrates women's shifting roles and increasing access to information. The novel’s complex narrative, enriched by its serialized format and the accompanying illustrations in Harper’s Weekly, emphasizes the tension between secrecy and the desire for truth. The varying settings, such as the contrasting environments of the Verinder estate and the Sands, further highlight how knowledge is distributed across different social and geographical spaces and question what places can contain knowledge or secrecy. Collins uses the pursuit of knowledge to drive his mystery, shedding light on broader societal shifts and the growing influence of information in the Victorian era. By looking at the elements surrounding its serialized format, the text's characteristics and motifs become more tangible, allowing posterior readers to examine important narrative tensions relevant to Victorian audiences.

Works Cited

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone. Oxford University Press, 2019.

Leighton, Mary Elizabeth, and Lisa Surridge. “The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper’s Weekly.” Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 42, no. 3, 2009, pp. 207–43. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27760229. Accessed 6 Dec. 2024.