Second Period. First Narrative. Chapter 4-5. Ryan Hurl

Comparing The Moonstone (1868), serialized in All the Year Round in Britain and Harper's Weekly in America, reveals how Drusilla Clack's religious dogma underscores 19th-century transatlantic contrasts in religion, gender, and morality. As a narrator, Drucilla Clack embodies cultural anxieties tied to religious contexts unique to national identities. In Britain, where the Church of England dominated, Clack’s piety becomes a recognizable source of satire—fanatical and disruptive, reflecting an evangelical pressure to cling to tradition with literal fervor. Within the pages of All the Year Round, Collins critiques religious agency through Clack as performative—a hollow adherence to familial legacy and Victorian morality, destabilized by zealotry and rigid interpretations of faith. Clack, who describes herself as representing “the only people who are always right” (Collins 221), exemplifies the tensions within the Church of England, tensions that take on new dimensions when contrasted with American Evangelicalism.

Larsen situates the timeline of The Moonstone within a “Crisis of Faith,” describing it as a product of Victorian religiosity and the growing divide through a split in common thought, to include Evangelicalism. He notes that faith, while publicly venerated, was widely discussed “not so much because society prized faith so much as they feared for its loss” (Larsen 10). Chadwick observes that Evangelicals within the Church of England sought reform “of the heart,” addressing spirituality’s declining influence in education and politics (Chadwick 442) the solution being a hard resolute return to absolutism in interpreting and following scripture. Through Clack, Collins critiques the Evangelical movement for amplifying expectation of religious authority by stunting societal progress, reflecting the shifting religious dynamics of the Victorian era.

In America, by contrast, Evangelicalism emphasized moral autonomy and individual responsibility, rooted in a history of dissent. Clack’s assertion that “the true Christian never yields” (Collins 221) resonates differently in an independent American context, appearing less extreme and reframing how a publication like Harpers could balance and negotiate Collins’s satire for an American audience. By engaging distinct cultural audiences through editorial and visual nuances, The Moonstone demonstrates serialized fiction’s adaptability in navigating diverse cultural paradigms through the lens of satire, underscoring how context shapes humor and critique.

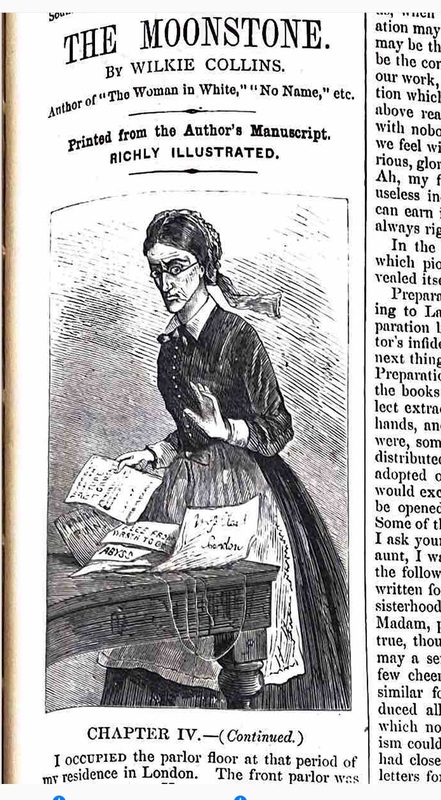

The illustration of Drusilla Clack in Harper's Weekly (Chapter IV—(Continued)) diverges sharply from Victorian ideals of feminine gentility, presenting Clack with angular features and a stern, commanding expression. This masculinized portrayal frames Clack as an unsettling figure whose comand disrupts conventional gender expectations. While Clack's manifesto in the installment—where she defends her moral crusade by declaring, “[the] true Christian never yields…we are above reason; we are beyond ridicule; we see with nobody's eyes…we feel with nobody's heart, but our own” (Collins 261) might resonate with American readers steeped in Evangelical traditions, her visual depiction undermines this potential alignment by transgressing norms of Victorian femininity. This divergence re-frames the humor in Collins’s satire, particularly regarding Clack's obsession with, “The Serpent at Home,” as well as Clack’s mission to expose and combat “evil” in the mundane actions of daily life. Clack's drive contrasts starkly with the nurturing, moral ideal of the regarded 'Angel of the House,' instead portraying Clack's position as hostile and overzealous.

Victorian American audiences, accustomed to valuing personal faith over institutionalized religion, might initially find common ground with Clack’s pious autonomy, which reflects new expressions of Christianity in a post-Church of England context. However, her visual portrayal complicates this alignment. The illustration positions Clack not as a virtuous reformer but as an aggressive, defeminized figure, subverting ideals of ladylike decorum and reframing Clack as an outsider. While her manifesto aligns with Evangelical ideals, her stern and alienating depiction declares her role as a recognizable satirical figure, subverting the association of moral agency with traditional gender expectations, as a type of cultural cue.

Clack’s pictorial representation signals a different, subtle cue to American readers. Although her rhetoric and actions may align with Evangelical values, the engraving juxtaposes her depiction against cultural ideals of Christian womanhood and religious legacy. This tension highlights a uniquely American perspective: Clack embodies Evangelical zeal but disrupts gender norms, reflecting Harper's Weekly’s nuanced approach to presenting transatlantic serialized fiction within the framework of varying religious and historical contexts of a culture liberated, yet still in touch with British publications.

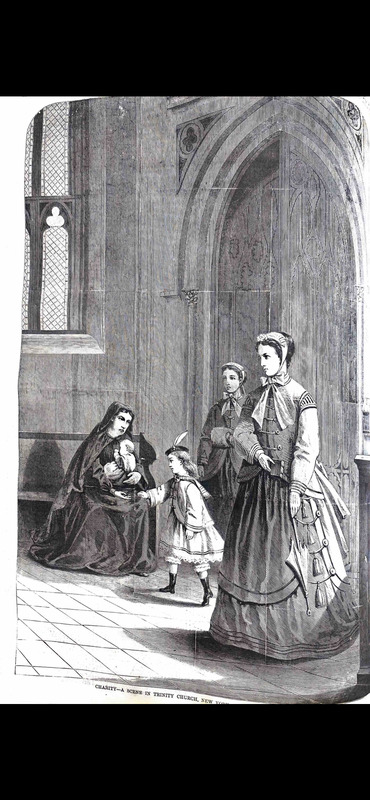

The engraving "Charity—A Scene in Trinity Church, New York" in Harper's Weekly contrasts with Clack's depiction in this installment of The Moonstone, offering insights into American religious values. The engraving reinforces recognizable Victorian norms by portraying women serenely engaging in acts of charity within the grand architectural space of Trinity Church. Unlike Clack's intrusive fervor, the women exemplify a harmonious integration of piety and societal expectations, reinforcing an upper-class hierarchy that supports the lower. For an American audience, this depiction normalizes religious charity as a public virtue aligned with communal ideals, whereas Clack’s charity—marked by self-serving rightousness—appears eccentric and disruptive due to an overreach of household comand.

Clack describes her participation in charitable efforts like “The Mother’s-Small-Clothes,” distributing Christian tracts disguised as benevolence: “[different] hands to address letters to Aunt Verinder to be placed, exciting no suspicion” (Collins 261), demonstrating here comparable perspectives with American parish charity. While reflecting Evangelical values of personal responsibility, Clack’s aggressive methods sharply contrast with the composed femininity in W.D. Washington’s engraving, emphasizing the importance of appearance in the character rendering at the start of the installment. Melnyk contextualizes women’s roles in church charity as functional and socially acceptable,signifying acts like visiting the poor and managing parish operations (Melnyk 129) roles Clack seems to adhere to earnestly in her view.

Washington’s engraving underscores Clack’s failure to embody socially acceptable femininity when positioned next to her Moonstone character illustration. Clack’s acknowledgment, “Preparation by books had failed” (Collins 226) reveals her commitment to expansive charitable perseverance. The serene women in the engraving, however, highlight Clack’s alienation from British and American ideals of femininity. Thus, while British readers dismissed Clack’s zeal as humorous overreach, American readers might instead focus on how Clack’s actions disrupt gender norms. The imagery ultimately highlights America as a distinct religious space defined by Anglican and Evangelical influences, which persist not as fringe secular developments but as central independent cultural forces.

Boughton’s Puritans engraving affirms the departure from the Church of England as a cornerstone of American identity, providing further evidence of the masculinization of the feminine as satire in the Clack installment of The Moonstone. The image depicts settlers defending spiritual devotion with pragmatic action, encapsulating the American cultural memory of religious endurance. The image reflects a foundational belief in integrating faith into daily life, portraying religious practice as essential to survival and governance. Houghton notes that while Victorian society experienced an Evangelical revival influential among the middle class, such revivalism in America took root in sects like the Puritans, who broke away from England (Houghton 359). The engraving underscores the risks of breaking away from British control, portraying men armed to defend worship and symbolizing the hostility and persecution central to American historical identity.

When Clack hides behind the curtains to observe Godfrey and Rachel in the Harpers edition of The Moonstone, her invisibility mirrors the Puritan principle of enduring religious hostility, symbolizing resilience in a new frontier, while serving as metaphor for the watchful eye of tradition. Godfrey’s statement, “I break the agreement, Rachel, every time I see you,” met with Rachel's reply, “Then don’t see me” (262), parallels the isolation and fixed conviction experienced by Puritans, once dismissed as radicals, unseen by British establishment as legitimate. Remaining unseen yet resilient cultivated a sense of martyrdom in early American Christianity, deffinitive in Clack’s personal self-image, and actions.

A Puritan cultural backdrop helps explain why Clack’s evangelicalism might resonate differently with American readers. For a society that valorized Puritan moral determination, Clack’s “mission” could evoke admiration rather than ridicule. However, her masculinized and intrusive actions, which lack traditional feminine virtue, cast her as a radical figure whose voyeuristic narrative account highlights her inability to navigate societal norms. Through illustrative cues, humor arises not from her inability to “save” her targets—a stark contrast to the framing in All the Year Round—but from her rejection of traditional femininity through an aggressive, exaggerated masculine demeanor.

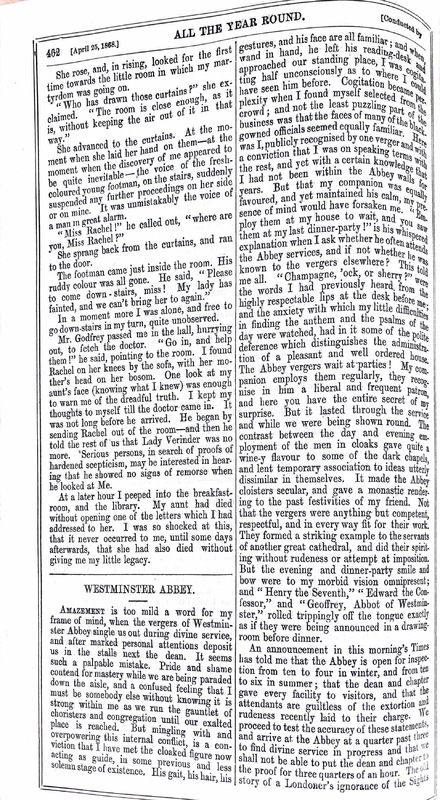

British readers would interpret Collins’s satire differently, situating Drucilla Clack's fervour within the broader framework of Victorian anxieties centered on faith's evolving role. In All the Year Round, Clack's intrusive evangelism is juxtaposed with a reverential article on Westminster Abbey, a bastion of institutional Anglicanism. The Abbey is described as “the temple of silence and reconciliation, where the enmities of twenty generations lie buried” (462), symbolizing restrained tradition and communal religiosity. The close relationship between church and state in 19th-century England re-frames Clack's actions within concerns about faith’s role in deathbed rituals and the literal interpretation of the threat of a tangible hell, lossing the ability to hold a culture in states of devotion. This pairing underscores the severity of religious doubt while highlighting, through Clack, the unsettling nature of personal piety in an era of waning religious certainty.

The Abbey, with its “competent, respectful, and in every way fit” vergers and its monuments “agreeably clean after St. Paul’s” (462), embodies dignity and collective spirituality. By placing an article idolizing the Abbey alongside Clack's evangelical fervour, the editorial context casts her actions as disruptive and performative in contradiction to the humbled grief of receiving a “legacy” (262). Clack’s moral crusade sharply contrasts with the decorum embodied by the Abbey, where one might “[meditate] upon the monument of Pitt or Fox without fear of annoyance or interruption” (463), a reverent demonstration of the church itself as an institution of hierarchy and order. The Abbey’s reverence for authenticity—celebrating the “humble graves of people who have never known ambition or tasted greatness” (464) only further accentuates Clack’s failure to embody the communal values upheld by institutional Anglicanism, lost to a crusade founded on literal interpretations of texts, which Collins infers veil personal agendas or power grabs without rational discourse.

Clack defends her actions, declaring, “Neither public nor private influences produce the slightest effect on us when we have once got our mission” (261). Yet her relentless intrusions into the Verinder household, especially her attempts to monitor Aunt Verinder, Rachel and Godfrey, reflect obsessive behaviour at odds with the Abbey's restrained pragmatic pride. The juxtaposition redefines Clack’s framing in All the Year Round, contrasting British anxieties about fragmented faith with the more sympathetic reception of Evangelicalism in America. While British readers align Clack’s exaggerated piety with fears of unchecked religious zeal, her actions also reflect broader Victorian tensions: the separation of church and state, the clash between institutional faith and scientific inquiry, and the redefinition of legacy and meaning within an increasingly secular society.

Conclusion

The varied symbolic framing of Drucilla Clack in The Moonstone demonstrates the transatlantic negotiation of religious and gender norms in contrasting American and British serialized literature. In Britain, Clack's Evangelical resolve is a source of humour and critique, underscoring the Victorian preference for restrained, institutionalized piety and skepticism toward religious literalism. In America, Clack's actions resonate with evangelical individualism, shifting the representation to mock and challenge gendered expectations, achieving narrative satirical relevance. By adapting Clack's portrayal to align with the cultural values of distinct audiences, Collins's serialized installments illustrate the fluidity of serialized fiction as a medium, mutable to editorial placement when devising meaning through context. Clack's character can serve as a lens for examining 19th-century anxieties about faith, femininity, and morality during a period of transformation.

Works Cited

“Boughton’s Puritans.” Harper’s Weekly, vol. 12, no. 591, Apr. 1868, p. 265. EBSCOhost, https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=h9m&AN=66926621&site=ehost-live&kw=true&acc=false&lpId=divl022&ppId=divp0009&twPV=&xOff=0&yOff=0&zm=fit&fs=&rot=0&docMapOpen=true&pageMapOpen=true.

“Charity—A Scene in Trinity Church, New York.” Harper’s Weekly, vol. 12, no. 591, Apr. 1868, p. 264. EBSCOhost, https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=h9m&AN=66926621&site=ehost-live&kw=true&acc=false&lpId=divl021&ppId=divp0008&twPV=&xOff=0&yOff=0&zm=fit&fs=&rot=0&docMapOpen=true&pageMapOpen=true.

Chadwick, Owen. The Victorian Church. 1966. A. And C. Black LTD London, pp. 440-443.

Collins, Wilkie. “The Moonstone: Chapter IV.” Harper’s Weekly, vol. 12, no. 591, Apr. 1868, p. 261. EBSCOhost, https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=h9m&AN=66926635&site=ehost-live&kw=true&acc=false&lpId=divl016&ppId=divp0005&twPV=&xOff=0&yOff=0&zm=fit&fs=&rot=0&docMapOpen=true&pageMapOpen=true.

---. The Moonstone. Oxford University Press, 2019.

“Drucilla Clack Illustration.” Harper’s Weekly, vol. 12, no. 591, Apr. 1868, p. 261. https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=h9m&AN=66926635&site=ehost-live&kw=true&acc=false&lpId=divl016&ppId=divp0005&twPV=&xOff=0&yOff=0&zm=fit&fs=&rot=0&docMapOpen=true&pageMapOpen=true.

Green, S. J. D. (Simon J. D.). The Passing of Protestant England: Secularisation and Social Change, 1920-1960. Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Houghton, Walter E. (Walter Edwards). The Victorian Frame of Mind, 1830-1870. 1957. Yale University Press, New Haven, p. 359.

Larsen, Timothy. Crisis of Doubt: Honest Faith in Nineteenth-Century England. 1st ed., Oxford University Press, 2006, pp. 9-11.

“Westminster Abbey.” All the Year Round, 25 Apr. 1868, pp. 462-466. Dickens Journals Online, https://www.djo.org.uk/all-the-year-round/volume-xix/page-462.html.