Part 25 - Sarah Henry

The issue of gender concerning the opportunities and expectations of Victorian-era women compared to men is reflected in the different publications of Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone as readers from different sides of the Atlantic are influenced to empathize with the novel’s characters. The June 20th publication of The Moonstone’s third narrative, chapter seven sees Rachel and Franklin struggle to find common ground within their relationship as so much of what has impacted them is due to miscommunication. Still, Rachel is trying to protect Franklin’s virtue at her own expense because of her strong feelings for him. Therefore, the supplementary materials offered alongside the installment of The Moonstone in both Harper’s Weekly and All the Year Round play into public opinion regarding matters of gender and class. Charles Dickens's All the Year Round appears as a less commercialized publication compared to its American counterpart Harper’s Weekly which suggests it has less political influence yet, the secondary texts reassert the gendered concerns presented in this chapter of The Moonstone. Both publications cater to the rising discourse of women’s equality but when looking at Harper’s Weekly compared to All the Year Round, the American publication appears to be aimed at a wider range of readers whereas Dickens’s publication is simple and consistent in its delivery of texts and therefore targeted at those most educated. Harper’s Weekly and All the Year Round were not marketed as feminist publications, yet the discourse surrounding gender equality is reflected in both as it was becoming an increasingly popular topic in Britain and “the situation was no better across the Atlantic” (Levine 295). Publications from both sides of the Atlantic comment on the rising public discourse surrounding gender equality in the Victorian era in ways that cater to the tastes and opinions of their readers.

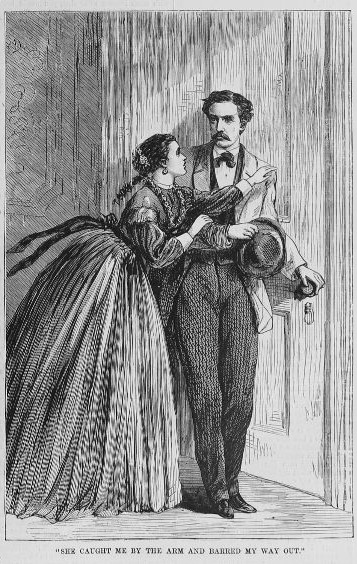

Harper’s Weekly supports its publication with numerous illustrations that depict the most important moments of this chapter of The Moonstone that both support and influence the readers' perception of the text. The largest illustration in this chapter depicts the altercation between Rachel and Franklin where she tries to keep him from leaving her room to finally discuss the events of the night of the theft. This illustration strengthens the message being conveyed in this scene where Rachel is desperately trying to be heard when so much of her experience has been told from the perspective of those around her. The novel is told by various narrators who comment on Rachel’s position and character, yet readers never hear from her directly. This illustration shows her taking back her voice and as she is depicted taking physical space from Franklin, it argues against the strict gender roles of the time. Phillipa Levine argues that “women's interests were generally either passed over or subjected to ridicule” in mainstream Victorian periodicals which reinforces the beliefs of the era where women were not granted equality due to gender (294). Female readers in America would have experienced this scene differently than British readers because of the added illustrations that humanize Rachel specifically and allow readers to visualize the desperation of her actions to take back her own narrative. This illustration speaks to the perspectives of the female readers who could relate to Rachel’s diligence and self-sacrifice to protect the man she loves as women in the Victorian era were not granted the same freedoms as men. Female readers could see themselves represented in ways that gave them identity in ways that society did not allow and provided motivation for them to create spaces of their own.

William Black’s novel Love or Marriage? being promoted by its publisher stands out amongst the advertisements in Harper’s Weekly as it subtly draws attention to the argument Franklin and Rachel have in this issue’s chapter. Rachel finally confronts Franklin about his peculiar actions leading to the theft of the moonstone and explains why she continues to cover for him despite him seemingly not deserving her kindness. In the American version of The Moonstone, this advertisement would likely have catered to the perspectives of the female readers who were held to a certain standard because of their gender and class, forcing them to choose between love or marriage. Rachel herself makes this choice numerous times throughout the novel when external pressures over her finances and future push her to accept a proposal she does not truly want. She reluctantly agrees to marry Godfrey Ablewhite when it becomes clear to her that love does not guarantee marriage and for a woman in her position, there were strong societal influences that led her to choose a safe option. Rachel loves Franklin despite believing that he is the thief of the moonstone and continues to protect his character throughout the novel. Love versus marriage is a major plot point in Rachel’s story as she grapples with her love for Franklin who has darkened his image with his involvement with the moonstone theft and Godfrey Abelwhite who she does not love, but momentarily agrees to marry on terms of protection and social expectations. The advertisement raises a question that Rachel and women alike would have considered especially when Victorian marriage standards for upper-class women placed greater importance on safety and financial security than love.

In a similar fashion to the secondary content in Harper’s Weekly, the British publication All the Year Round supports its publication of The Moonstone with texts that reinforce the main points Wilkie Collins is making in his novel. The poem titled “Something Left” discusses the significance of love in making a person feel content even if they have nothing else. This poem, its declaration that love is worth more than wealth or beauty, ties in with Rachel’s actions toward Franklin even when she knew that he took her diamond, she continued to protect him and “suffered the consequences of concealing it” (Collins 341). Despite caring so deeply for Franklin, she turns him away when he kisses her because she does not want to build a relationship on lies if she and Franklin can not be equals. The influence of the poem on the reader’s perception of this scene highlights Rachel's willingness to make sacrifices at her own expense as she tells Franklin she “would have lost fifty diamonds, rather than see your face lying to me, as I see it lying now!” (Collins 348). All she wants is for Franklin to be honest with her and to treat her with the same care and respect that Victorian women were pushing for in rising feminist movements. The audience who would have been reading this volume of All the Year Round looked to this publication for social commentary and criticism as issues of gender equality and women’s rights were prevalent in late Victorian Britain. Therefore, the inclusion of “Something Left” pushed the reader to consider women's motives, considerably those of higher class who in this period had fewer opportunities to make choices for and by themselves.

Another excerpt from All the Year Round that supports the efforts of women in the late Victorian era to push for equality is from the short work “Town and Country Sparrows”. In this story, the author writes about the biological nature of male sparrows fighting with other males over their claim to their female counterparts. This dominant behaviour represents Franklin’s brash actions toward Rachel who did not return his affection because she believed he had stolen from her. The actions depicted in “Town and Country Sparrows” support Rachel’s claim that “It seems a cowardly surprise, to surprise [her] into letting [Franklin] kiss [her]” by using her affection for him as a way to get something from her (Collins 341). This scene of dominance that arises from gender inequality also is representative of Franklin stealing the moonstone as it took unprompted entry into Rachel’s room, acting as an extension of her bodily autonomy. Rachel claims that her perspective is “only a woman’s view” and she ought to have known Franklin as a man could not have shared it (Collins 341). This story draws attention to gender inequality and the rising social discourse and feminist movements pushing for the equal treatment of women in a male-dominated society. How these ideas are presented to the readers when compared to Harper's Weekly suggests that it targeted the system and therefore readers that resisted this social and political development to influence significant change. Periodicals were places to find social commentary and in this specific volume, the issue of gender inequality was at the forefront and supplementary material was used to further push the narrative that society needed to change.

The two different publications provide context with supplementary material that suggests the promotion of gender equality discourse was served to different types of readers in supportive ways. For the issue of Harper’s Weekly, the advertisements and illustrations cater to the female perspective and promote the association with Rachel. The American periodical emphasizes gendered concerns especially those for women in its inclusion of tailored advertisements that comment on marriage as a construct, secondary to a chapter of The Moonstone which showcases Rachel reclaiming her individuality from the men in her life. With its illustrations and pictures, it also caters to a wider range of readers making Harper’s Weekly more suited to a family dynamic where members of all ages could engage with the text. The British periodical represents a society of readers who expected a consistent level of intellectual prose and thus opinion towards gender and equality was best presented through poetry and short stories. The simple layout does not showcase illustrations or advertisements but contains only short pieces of fiction that suggest it was tailored toward upper-class readers. Despite its plain appearance, the supplementary texts of “Town and Country Sparrows” and “Something Left” compliment Rachel’s thoughts and actions in this issue’s chapter in a manner that is subtle considering that readers of All the Year Round were likely to be upper class and educated. The Victorian period saw the rise of public discourse surrounding marital law and women's rights, which is reflected in the content of both Harper’s Weekly and All the Year Round. While the legislation had not yet granted women the legal right to a separate identity from their husbands at the time of these publications, it was a movement gaining momentum in both the United States and Britain and is therefore reflected in the popular publications of the time.

Works Cited

All the year round, vol. 20, no. 478, 1868, pp. 25-48. ProQuest, https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-periodicals%2Fmoonstone%2Fdocview%2F7881042%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D9838.

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone. Arcturus Publishing LTD, 2017.

Harper's Weekly, 20 June 1868. American Historical Periodicals from the American Antiquarian Society, http://link-gale-com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/apps/doc/CNTRSO092332352/AAHP?u=ucalgary&sid=bookmark-AAHP&xid=00b1f88b. Accessed 26 Nov. 2024.

Levine, Phillipa. ""The Humanising Influences of Five O'clock Tea": Victorian Feminist Periodicals." Victorian Studies, vol. 33, no. 2, 1990, pp. 293. ProQuest, https://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fscholarly-journals%2Fhumanising-influences-five-oclock-tea-victorian%2Fdocview%2F1304754853%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D9838.