Part 26: Third Narrative, Chapter 8 - Stella Tilinger

The most striking difference between the Harper's publication of The Moonstone and the publication in All The Year Round is the presence - or lack of - illustrations. While both publications were respected in their own countries (Harper’s in the United States, and All The Year Round in the United Kingdom), they were known for entirely different things. Harper’s had a mandate to provide high-quality letterpress with exceptional woodcut illustrations to go along with its articles and stories. All The Year Round lacked that but contained curated pieces picked by Charles Dickens and was beloved by its local audience. However, the illustrations in the American version of The Moonstone give the text an entirely different effect, adding an “intricate visual layer to the already complex narrative structure” (Leighton and Surridge, 210). Harper's achieved this through dramatic visuals that leaned into the sensationalism of the story - something that All The Year Round could not do, as within the dramatic visuals, Harper's also launched critiques against the still-ongoing colonialist behaviours of the British that a magazine from the United Kingdom would never dare print. This article will compare the illustrations and titling of The Moonstone in Harper’s to the titling and surrounding context of the same excerpt in All The Year Round, showing how Harper’s brings the reader further into the discourse of the story while All The Year Round treats the chapter as simply another of its many selected features.

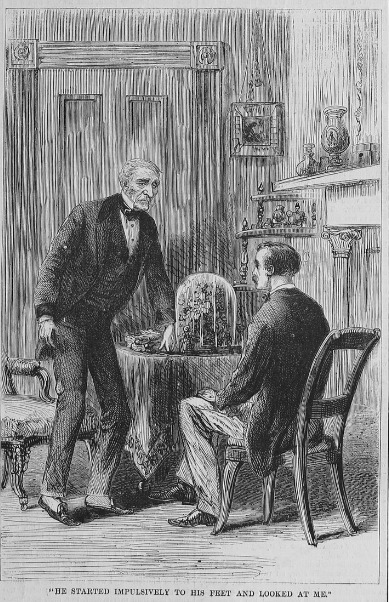

Collins often used illustrations to emphasize the divide between characters or highlight critical points of their personalities. In the first chapters of The Moonstone featured in Harper’s, the illustrations serve not only as an addition to the story but a way to “critique of British domination by focussing on the diamond as Indian rather than British possession: the chapter head showing the diamond in the shrine at Benares with Indian worshippers kneeling before it strongly suggests that the stone's rightful place lies in Indian culture” (Leighton and Surridge 213). These illustrations were a double-edged blade, with the dramatic illustrations often contributing to the novel’s reputation as “sensationalist.” Illustrations of these sensationalist pieces of fiction often tended to deploy visual elements that employed tropes to create a sense of atmospheric turbulence or boundary-crossing. In this scene, Franklin Blake attempts to jog the memory of the doctor, Mr. Candy, in order to gain clarity about the location of the titular moonstone. Mr. Candy is aged, sickened, and “pitiably plain that he was aware of his own defect of memory, and that he was bent on hiding it from the observation of his friends” (Collins, 352), and Franklin Blake is utterly unimpressed by his behaviour in his search for answers. Candy fidgets, jumping in and out of his seat and stiffly responding to Blake’s impatient questioning over what, exactly, Candy wanted to say to him at the birthday party over a year previous. The illustration itself shows Candy supporting himself with the table, staring at Blake’s face as if he’s looking down upon a disobedient grandchild. In contrast to his unsteady posture, Blake is shown sitting down and the audience can only see part of his face, mirroring how Candy barely grasps exactly what Blake is getting at as the questions continue. Blake is upright and solid, watching Candy pitch back and forth and lapse in memory with a dire expression as his hope dwindles. Behind them, a door stands closed - a line of symbolic crossing. Harper’s chapter illustrators were purposefully careful with how they utilized shadow and light to dramatize the scene, which extended to the entire page around each illustration.

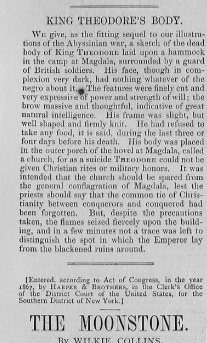

The title of The Moonstone was not free of the illustrator’s touches in Harper’s. In previous publications, as the mystery initially builds, the “motif of darkness and mystery is taken up in the dark chapter heads that frame the novel's early installments” (Leighton and Surridge 218). By this point in the story, the threads are being wrapped up - the mystery is coming to light. Instead of the dark scenes of Indians being struck down in pursuit of the moonstone, as Roseanna’s death has faded from immediate memory and as the characters have gone their separate ways after recovering from the initial trauma of that confusing night, we literally have light being shone on the topic. In reflection of this, the chapter heads are no longer dark, but instead written with slim letters that show the white background of the paper beneath them. The period at the end of the title brings an air of finality and factuality to the article, and the heading includes praise of Wilkie Collins. Interestingly, the unfolding mystery is published directly beneath an article speaking of the death of King Tewodros II while battling in Ethiopia. Tewodros, referred to by the English cognate Theodore, perished in a conflict with Great Britain that was sparked after a final breach of diplomatic immunity. The Moonstone as a story begins with a conflict in a foreign land, and the illustrators were more than happy to emphasize the power imbalance between the British troops and Indian civilians that resulted in the theft of the moonstone to begin with. The placement of this installment of The Moonstone under a news article chronicling the untimely death of an Ethiopian king (with a corresponding illustration being shown on the opposite page to The Moonstone), while perhaps coincidental, is at the very least an ironic twist of fate - or even a commentary on the world through the lens of The Moonstone.

In contrast to the title card in Harper’s, All The Year Round emphasizes its own standing as a publication. Harper’s did not have a heading above every page, while All The Year Round proudly states it is “conducted by Charles Dickens” and features a Shakespeare quote above its title. All The Year Round entirely lacks illustrations in The Moonstone, as with other articles and periodicals published in its pages. Advertisements are large blocks of text in various bolded fonts, all fighting to entice readers simply by being larger and louder than the others. Wilkie Collins is not named in All The Year Round above his own piece, instead being credited as “the author of The Woman in White” with no further explanation. While Collins may have been popular in his native England, with the aforementioned novel The Woman in White coming out in 1859, the fact that All The Year Round fails to tie his name to his work is interesting in comparison to Harper’s. All The Year Round seems to cater to a more serious audience, in that aspect - rather than adding perceived “fun” to the story in the form of illustrations, it abandons those entirely and gets straight to the point of the story. While this is fine for the English audience, it also lacks the added layer of critical commentary provided by the illustrations. Harper’s, as mentioned, criticized the actions of Herncastle and other soldiers who mythologized the moonstone to such an extent that it resulted in a frenetic murder. All The Year Round could not possibly espouse the same criticisms to the general public, who may themselves have been soldiers who went to similar places, when the colonies were still viewed as places barbaric enough to send prisoners as punishment. Instead, The Moonstone was surrounded by advertisements - some of which were, nonetheless, equally as amusing as illustrations in context of the story.

Initially unassuming, an advertisement advertising travelling dresses and bags becomes all the more amusing when placed beside The Moonstone, which follows two thefts and international trips of the same diamond while the characters around the gem panickedly follow it throughout the countries. While not specifically crafted for the story, the advertisement still serves as a form of extra-textual commentary on the story. The Moonstone is written as a collection of papers and accounts from various characters, all telling the singular story of the moonstone’s theft, and we as the audience travel through the story with the characters. Nobody is omnipotent; we, as the readers, uncover information at the same moments as the characters do until the very end when Franklin Blake compiles the papers submitted to him and embarks on his own journey to bring the mystery to a close. All The Year Round unintentionally emphasizes how the story overall is one large journey - both for the audience, following along with the mystery, and for the diamond, which has been passed from hand to hand countless times as characters chase it throughout the English countryside. The lack of illustrations ties into this, as it cuts to the point of the story rather than introducing more nuance with illustrations of the characters. Even in an illustration so simple as the previously shown image between Dr. Candy and Franklin Blake, the characters are visibly pushing against one another in everything from their postures to how they are lit and how they are positioned within the room. The travel ad in All The Year Round, in contrast, cuts straight to the point. The offerings are listed in bold font, followed by prices and a location to contact the seller in a no-nonsense manner. Harper’s leans into the sensation of The Moonstone, while All The Year Round is too serious to put sensation in anything- even something so minor as an advertisement.

In conclusion, although not always reprinted, the illustrations accompanying The Moonstone that were provided by Harper’s are vital to the entire experience of the novel. While both the United Kingdom and the American versions contain the same wording, the same chapters, and the same base story, All The Year Round cannot offer the level of critique and metatextual discussion offered by Harper’s for the sole reason of the lack of illustration. At the time, the illustrations only led credence to the claims that decried the novel as “sensationalism,” but they provided the criticism that Collins carefully wove into his novel in a much more overt manner. This perspective is more easily seen today, and for students reading The Moonstone today, the illustrations are an essential component of the novel that entirely transforms it from the United Kingdom’s straightforward delivery of the story into not only a dramatic mystery but a delicate critique of contemporary issues.

Works Cited:

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone. Penguin Classics,1999

Dickens, Charles. All the Year Round (London : 1868). Chapman & Hall, 1868.

Leighton, Mary Elizabeth and Lisa Surridge. "The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper's Weekly." Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 42 no. 3, 2009, pp. 207-243.

"Title Page." Harper's Weekly, 27 June 1868. American Historical Periodicals from the American Antiquarian Society, link-gale-com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/apps/doc/YUWZTP210471868/AAHP?u=ucalgary&sid=bookmark-AAHP&xid=0b6c71ba. Accessed 19 Nov. 2024